The Making of the Irish Border, 1912-1925, a Short History

By John Dorney

By John Dorney

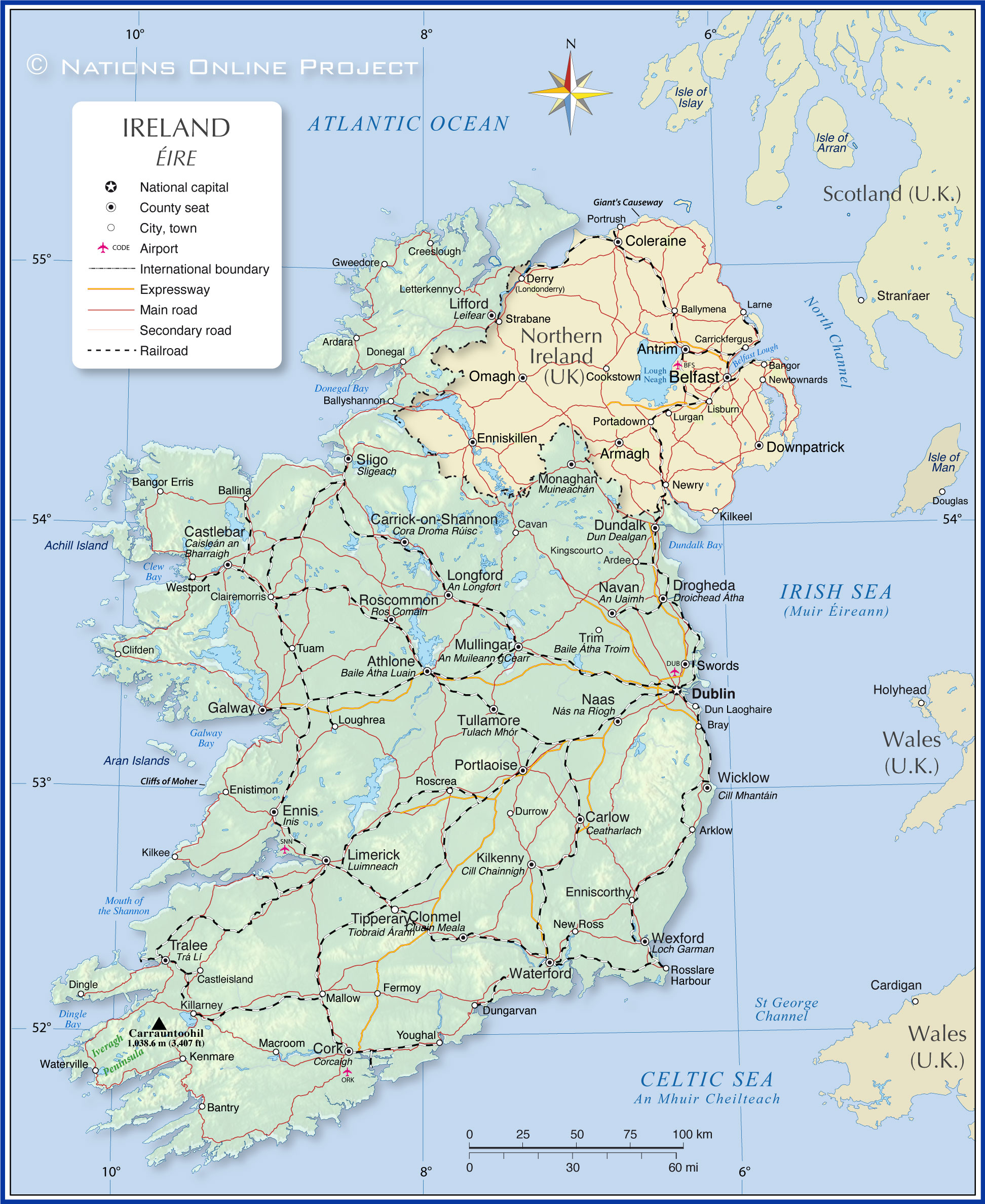

On a recent visit to Clones County Monaghan, coming from Cavan town, I had to travel six times across the Irish border. Both towns are in the Republic of Ireland. Clones, once a thriving market town, was cut off by partition from its natural hinterland in county Fermanagh.

Today its grand nineteenth century buildings are largely derelict, its railway station closed, its market square quiet.

During the Troubles, I was told, the border between here and Cavan was impossible to police, wafers of each jurisdiction on the main road are surrounded by high ground in the other. Police, especially RUC checkpoints, were vulnerable to gunmen in the hills.

Today (September 2019) ,with the imminent departure of the United Kingdom from the European Union, towns such as Clones face the prospect of the border closing again, at the least to erect customs posts, at worst, perhaps again to be guarded by armed police and soldiers.

How did such a border, one that lazily cuts through villages and farms, following no appreciable natural boundary, come to be?

Ulster says no

While the divisions in Ireland between the north and the south and between Catholics and Protestants can be dated back, at least, to the seventeenth century, the story of the Irish border begins, in essence with the Home Rule crisis of 1912 to 1914.

Northern Unionists, overwhelming Protestant and concentrated in east Ulster, mobilised to resist Home Rule or Irish self-government, that was being passed through the British Parliament by the Liberal Party.

They did this first by mass mobilisation, signing the Ulster Covenant, and then in arms, forming and arming their own militia, the Ulster Volunteer Force, to thwart Home Rule.

Unionist mobilisation in 1912-14 meant that Ulster was excluded from Home Rule in 1914.

Though the initial unionist objective was to block Home Rule for all of Ireland, their fall-back position was to exclude ‘Ulster’ from rule by a Dublin based, nationalist- dominated parliament. Such a parliament would, they argued be, ‘disastrous to the material well-being of Ulster as well as of the whole of Ireland, subversive of our civil and religious freedom, destructive of our citizenship, and perilous to the unity of the Empire’. [1]

The unionists were given financial and moral backing by influential elements of the Conservative Party and elements of the British Army officer corps indicated, during the ‘Curragh mutiny’ of 1914, that they would be unwilling to put down unionist militants to enforce Home Rule. All of which resulted in the Prime Minister Asquith agreeing in 1914 to exclude ‘Ulster’ (as yet an undefined term) from Home Rule.

John Redmond the leader of the nationalist Irish Parliamentary Party, agreed with Edward Carson, the unionist leader, temporarily, to exclude Ulster (he was told for period of three to six years) as a price for defusing potential civil war in Ireland in the summer of 1914. [2]

In the event, Home Rule was shelved for the duration of the Great War, which Britain entered in August 1914.

For Redmond, agreeing to the exclusion of north east Ulster from Home Rule was a temporary concession, for which he was bitterly criticised by other nationalists. But the Exclusion Act proved to be the germ of the permanent partition of Ireland.

Six Counties or Nine?

The key problem with partition, from the start, was that, while it might successfully segregate one minority, northern Unionists, from a government they did not wish to live under, it inevitably created another disenfranchised minority, northern Catholics and nationalists, within any area excluded from Irish self government.

For unionists the problem was two-fold. Some of their Ulster Protestant brethren lived in counties such as Donegal, Cavan and Monaghan, with strong nationalist majorities. Include these in a proposed northern state and nationalists would have near parity of numbers.

Unionists preferred a six country partition, where they had a safe majority, to all of Ulster in a proposed northern state.

So unionists in those counties, as well as those further south, had quietly to be sacrificed. While Edward Carson, a Dublin man, envisaged the exclusion of all of Ulster, he acknowledged at an early stage that, his ‘more extreme followers’ wanted only the six north eastern counties with a strong unionist majority. ‘They are apparently afraid that a big entire Ulster would gravitate towards a United Ireland’, he told the Prime Minister Asquith’.[3]

However, there was a second problem. If unionists were also to forgo the Ulster counties of Fermanagh and Tyrone, where nationalists were also in the majority, albeit slightly, the proposed unionist self governing area might be too small to be viable.

The dilemma for unionists therefore became territory versus demographics. Include too much territory and they might not be a safe majority, include too little and they would be confined to a strip of eastern Ulster.

On the nationalist side, there was also intransigence. In talks in 1914, John Redmond wanted each county to have the option of whether to live under the Dublin Home Rule parliament, which would have given his proposed parliament counties Fermanagh and Tyrone. Neither side could agree on the area of Ulster that would be excluded from Home Rule.

These points were thrashed out without results in further negotiations aimed an enacting Home Rule in 1916 and 1917. No agreement was reached.

The Government of Ireland Act, 1920

Home Rule was supposed to be enacted after the end of the First World War, but by the time the war had finally ended in the armistice of November 1918, (and formally with the treaties of 1919), Irish politics was unrecognisable from what it had been in 1914.

The Easter Rising of 1916 and its suppression, along with the conscription crisis of 1918 had greatly radicalised Irish nationalism. Sinn Fein, campaigning not for Home Rule but for an independent Irish Republic, had won a sweeping victory in the general election of December 1918.

From early in the following year, the guerrillas of the IRA began waging a guerrilla war against British rule. There was now less chance than ever of achieving a consensual solution such as Home Rule, partitioned or otherwise.

In 1920 the British government created two Home rule parliaments, one in Dublin and one in Belfast.

And so, the British government attempted to impose a solution unilaterally, the Government of Ireland Act; a solution that formally introduced a border into Ireland.

By this time David Lloyd George had succeeded Asquith as Prime Minister and though there was still a Liberal Prime Minister, his government was a coalition with Conservatives, close allies of the Ulster unionists.

Unionist leader William Craig was consulted before Lloyd George brought the Government of Ireland Bill before parliament on December 19, 1919, a Bill which proposed two Home Rule Parliaments; one in Dublin and another in Belfast, governing the six county area favoured by the unionists. [4]

Very few at the time thought that the partition contained in the Act would be permanent. It was not passed through parliament until August 1920 and did not come into effect until December of that year. What was more, the Belfast parliament did not actually meet until June 1921 (its southern equivalent never did).

By this time the British were also looking for a way to end the armed conflict with the Irish Republicans, which led to a truce in July 1921 and the opening of negotiations with Sinn Fein .

The Treaty

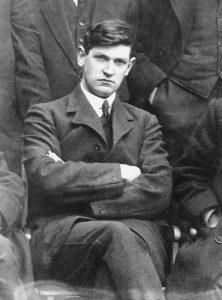

The Anglo Irish Treaty of December 1921, signed by the Irish negotiating team led by Michael Collins and Arthur Griffith and the British government, is often associated with the enduring border in Ireland.

This is something of a misconception, however. Lloyd George told the Irish negotiators at an early point in the talks that ‘whatever happens we will not coerce Ulster’.[5] In other words, partition was a pre-condition of the talks.

On November 9, 1921, well before any agreement had been reached with the Sinn Fein negotiators (or as they thought of themselves, representatives of the Dail or Republican parliament), the British government transferred Executive Powers to the new Northern Ireland government at Stormont. [6]

The Treaty of 1921 confirmed rather than introduced partition.

This gave it, among other things, responsibility for internal security and for policing, opening the prospect for the first time of real, functioning border. So, well before the signing of the Treaty, Northern Ireland was already a reality, with its own functioning government and security forces.

It was not until December 6, 1921 that the Treaty was signed, creating an Irish Free State in the other 26 counties, a self governing dominion of the British Empire.

While Collins, Griffith and their colleagues were against partition in principle, all they were able to extract from the British to ameliorate it was Article 12 of the Treaty. This allowed the Northern Ireland Parliament to opt out of the Free State, a result that was guaranteed by the area’s in-built unionist majority.

However, the Irish delegates believed that this could be offset by the provision of a Boundary Commission which would, ‘determine in accordance with the wishes of the inhabitants, so far as may be compatible with the economic and geographic conditions, the boundaries between Northern Ireland and the rest of Ireland’.[7]

It was assumed, certainly by supporters of the Treaty, that areas of Northern Ireland such as south Down, Newry, south Amagh and Derry city, as well as counties Fermanagh and Tyrone, all of whose local government bodies had been in nationalist hands since 1920, would be reassigned ‘in accordance with the wishes of their inhabitants’.

Michael Collins in particular, despite his signing of the Treaty, remained militantly against partition. He told the Northern Divisions of the IRA in early 1922 that, ‘although the Treaty may have seemed as an outward expression of partition, the [Provisional Irish] Government plans to make it [partition] impossible…even if it meant smashing the Treaty’.[8]

But it was not to be.

The ‘Border War’ of 1922

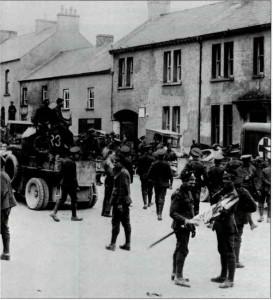

It would be a mistake to portray, as some accounts do, the beginnings of the Irish border as a tale merely of statecraft and diplomacy. Because the Irish border, like many other frontiers, was made real by bloodshed and violence in 1922.

The one thing that Collins and his former comrades, who opposed the Treaty and the Irish Free State, on the grounds that it did not deliver full Irish independence, could agree upon was that partition must be ended.

While Collins paid the salaries of teachers in Northern Ireland who recognised the Free State, and funded nationalist-controlled County Councils, he also agreed a ‘joint Northern policy’ with the anti-Treaty IRA under Liam Lynch. Together they sent men and weapons to, and across, the border.

The border was made real by armed conflict in 1922.

On the other side the Northern Ireland Government mobilised the Ulster Special Constabulary, a almost exclusively Protestant, armed force, 30,000 strong, to defend its territory.

What followed was a dirty, undeclared, war in the first half of 1922, punctuated by killings and reprisals on both sides. In Belfast in particular, several hundred civilians, of whom the majority were Catholics, died in the violence of early 1922.

On the new frontier itself, what the hostilities meant was that the border became ‘hard’ for the first time. The Ulster Specials blew up and blocked secondary roads and put fortified checkpoints on the main crossing points from south to north. They and local IRA units waged nightly gun battles. In the Cavan and Monaghan area, the local newspaper reported on March 18 that:

‘There is nightly firing across the border….‘Armed men face each other rifle in hand….Farmers will not till the land. There is no trade across the border. … ‘Men who lived with each other in perfect harmony and ridiculed the idea of the border now see what partition has brought about’.[9]

Intimidation of civilians occurred on both sides. Up to 20,000 Catholic refugees fled south and a significant, though as yet undetermined, number of southern Protestants sought refuge in the north. [10]

Ultimately the ‘border war’ ended in de facto victory for the Northern government. A planned IRA offensive of May 1922 collapsed amid disorganisation and contradictory orders. When IRA forces did defeat the Ulster Specials, as at the border villages of Pettigo and Belleek, they were in turn routed by regular British Army forces backed by artillery. [11] Facing internment in the North, most IRA volunteers there fled south. Those who stayed faced a range of punishments including imprisonment (in many cases until 1924) and flogging.

The outbreak of Civil War in the south on June 28, 1922 spelled the end of republican efforts to end partition. After the death of Michael Collins in the Civil War in late August, the Free State government quietly dropped his militant policies against Northern Ireland and resolved to wait for the results of the boundary commission promised by the Treaty.

While they were waiting, the southern Government after its successful suppression of anti-Treaty IRA, also contributed to the hardening of partition by erecting customs posts on the southern side of the border, to collect much needed revenue for the new state, in April 1923. [12]

The Boundary Commission

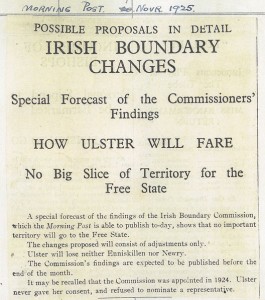

The final act in the making of the border came with the Boundary Commission of 1925. Many in the nationalist dominated southern and western edges of Northern Ireland expected that, if the border were to be redrawn ‘in accordance with the wishes of the inhabitants’, they would be transferred to the Free State.

The final act in the making of the border came with the Boundary Commission of 1925. Many in the nationalist dominated southern and western edges of Northern Ireland expected that, if the border were to be redrawn ‘in accordance with the wishes of the inhabitants’, they would be transferred to the Free State.

But the Commission had on it two British representatives, men of unionist sympathies, Richard Feetham and JR Fisher and one Irish nominee, Eoin MacNeill, the Minster for Education in the Free State.

Fisher and Feetham put greater emphasis on the second part of Article 12, which stated that any changes in border had to be compatible with ‘economic and geographic conditions’ and judged that their role was ‘not to reconstitute the two territories but to settle a boundary between them’. [13]

The Boundary Commission recommended no major changes to the border. Its report was never published.

Their final report recommended very minor changes, with part of south Armagh and south Down and strips of Tyrone and Fermanagh going to the Free State and a portion of County Donegal going over to Northern Ireland. Had it been implemented, the Boundary Commission report would have transferred 31,000 Northern citizens to the Free State and 7,500 southern citizens to Northern Ireland – a very minor adjustment of the border.[14]

In the meantime the Northern Government had in 1924 redrawn its own internal electoral boundaries so that even nationalist majority areas now elected unionist representatives.[15]

Fisher and Feetham kept the unionist leadership, including the now retired Edward Carson, abreast of their plans. The latter was delighted to hear that Northern Ireland was keeping the nationalist majority towns of Newry and Derry and all the other major towns in the six county area; ‘if anyone had told me 12 months ago I would have laughed at them’, he wrote.

The report of the Commission, when leaked to the press, was highly embarrassing for the Free State government. It managed to have the Boundary Commission proposals buried altogether (it was never published) and gave up any claim to Northern territory in return for being forgiven its share of Britain’s Imperial War Debt. The border stayed as it had been since 1922.

The Irish Government portrayed its secret deal positively, ‘we have sown the seeds of peace’ it announced,[16] but the contested border has remained the subject of bitter and sometimes violent contention ever since.

The contradiction, that a border designed to satisfy one minority create another, equally aggrieved one, was never really solved.

For a brief period, after the Good Friday Agreement of 1998 and inside a borderless European Union, it appeared as if the Irish border might fade away into insignificance. However today, with the impending exit of Britain from the EU, its future is highly uncertain.

References

[1] Joseph Connell, The Ulster Covenant, History Ireland, 2012.

[2] Ronan, Fanning, The Fatal Path, British Government and Irish Revolution 1910-1922, p. 101-104

[3] Fanning, p.123

[4] Fanning p215

[5] Fanning p280

[6] Fanning, p288

[7] Liam Weeks, Michael O Fatharthaigh, The Treaty, p.279

[8] Donnacha O Beachain, From Partition to Brexit, 2019, p. 13

[9] Anglo-Celt March 18 1922.

[10] The figure of 20,000 refugees in the Free State was reported in the Irish Independent in June 1922, government figures show over 1,500 being officially housed in Dublin, though many more were clustered in border areas. See John Dorney the Civil War in Dublin, p.52. Some 42,000 Protestants left the territory of the Free State between 1921 and 1923, though how many were forced out by violence or intimidation and how many went to Northern Ireland is unclear.

[11] See Patrick Concannon, Michael Collins and the Northern Offensive 1922.

[12] See for instance, Catherine Nash, Bryonie Reid, Partitioned Lives, The Irish Borderlands, on Customs here.

[13] O Beachain, Partition, p24

[14] O Beachain, p25,

[15] See John Dorney, Revisiting the Northern Ireland Civil Rights Movement.

[16] O Beachain, p27-30