Revisiting the Northern Ireland Civil Rights Movement: 1968-69

By John Dorney

This year, 2018, marks the fiftieth anniversary of the beginning of the Northern Ireland Civil Rights movement.

Its first major manifestation was a march in Dungannon in August 1968, in protest at the allocation of public housing by local government and was shortly followed by a smaller protest march in in Derry city. The Derry march, famously, was attacked by the Royal Ulster Constabulary (RUC), and images of bloodied marchers, including Member of Parliament Gerry Fitt, were broadcast via the Irish state television station RTE, first around Ireland and then around the world.

The Civil Rights movement began in 1968 and is now widely seen as the start of the Northern Ireland conflict.

The march in Derry on October 5, 1968 was followed by an intense series of protests and disturbances in that city. These culminated in intense rioting with the RUC in January 1969 after a Civil Rights march from Belfast to Derry by the left wing group People’s Democracy had come under sustained attack by loyalists. The fighting in Derry led to the sealing off of the working class nationalist district of the city – the Bogside and Creggan areas – from the police in early 1969, in what was known as ‘Free Derry’.

When in August of 1969, major rioting broke out again in Derry, ‘The Battle of the Bogside’ it quickly spread to Belfast, capital of Northern Ireland, where it claimed the lives of eight people and saw an entire Catholic street, Bombay Street, burned out by loyalists.[1]

The riots of August 1969 are usually viewed as the point of no return; the moment at which Northern Ireland slid inevitably into armed civil conflict as opposed to mere civil disturbances. Rival paramilitaries groups were formed and the British Army was deployed in large numbers into Northern Ireland for the first time since the 1920s.

Inevitably, in a society as polarised as Northern Ireland, rival, indeed, completely opposite, narratives exist about the Civil Rights movement. The nationalist or republican story, simply stated, is that the Civil Rights movement was a minimum set of democratic demands, including the provision of ‘one man one vote’, fair electoral boundaries and fair access to jobs and housing, by a Catholic, Nationalist population that had been oppressed since the foundation of Northern Ireland in 1922.

This peaceful movement was met with state and loyalist violence and so, nationalists inevitably turned to the use of force in self-defence. Since Northern Ireland had proved itself impervious to even moderate reform, so the narrative goes, many instead resorted to armed struggle to unify Ireland and to abolish the state of Northern Ireland altogether.

A ‘leading Provisional [IRA member]’ in 1971 for instance, stated, ‘we hate to see the loss of anyone’s life but… various forms of protest have been employed by the people against repression in Northern Ireland, but with little effect… there was an accumulation of evidence to me that really the Six County area is irreformable, we cannot change it’. [2]

Unionists, by contrast, argue that discrimination against Catholics in Northern Ireland before 1968 was minimal and confined to isolated areas of Northern Ireland. In the words of one unionist politician Graham Gudgin, ‘The allegations [of discrimination] are widely believed, even by unionists, but are hugely exaggerated… The abuses were limited and localised’[3].

Many unionists voice an opinion that there was no disadvantage suffered by working class nationalists that poor unionists did not also suffer. What discrimination there was, they argue, was the result of the fundamental disloyalty of a section of the population. The Civil Rights movement was, some argue, a front for the IRA from the start, or a far left organisation that deliberately provoked confrontation and escalated violence in 1968 and 1969.

Gregory Campbell of Derry for instance argues: They were campaigning for issues like housing conditions, jobs and votes – which the Protestant working class didn’t have either. Because of the very recent IRA campaign there were many in the unionist community who viewed that (civil rights) movement with extreme suspicion.[4]

This article will try to examine these arguments as dispassionately as possible. First, how bad was discrimination against Catholics in Northern Ireland? Second, were the tactics of the Civil Rights movement deliberately provocative? And thirdly, was Northern Ireland as it existed in 1968 fundamentally irreformable?

Discrimination in Northern Ireland 1922-1968

The essential point to grasp about discrimination against Catholics in Northern Ireland was that it was primarily political. It was designed to maintain unionist control of the Northern Ireland state; every other consideration was secondary.

So, where unionist control was perceived to be weak, discrimination in its most obvious forms; that is in voting, in ‘gerrymandering’ of electoral boundaries and in allocation of public housing, was at its worst.

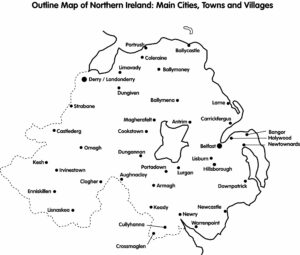

This occurred primarily in the west of Northern Ireland, where Catholics and nationalists were in a majority. Discrimination in all of these areas was much less pronounced in the east of Ulster, and particularly in Belfast, where, at the time, Protestants and unionists had a safe majority.

An academic report of 1983 into discrimination in Northern Ireland concluded that it was mostly ‘shades of grey rather than black and white’, but that in the west of Northern Ireland ‘the greyness of the picture over most of the province changes to an ominous darkness.’ The area west of the river Bann had only a quarter of Northern Ireland’s population but over two thirds of complaints of discrimination.[5]

Discrimination against Catholics in Northern Ireland was primarily designed to main unionist political dominance.

In Northern Ireland’s earliest days, it had very nearly lost the western counties of Fermanagh and Tyrone and Derry city. In local elections held under a proportional representation system in 1920, just before partition, Sinn Fein and the Irish Nationalist Party won control of Derry, Northern Ireland’s putative second city, and Fermanagh and Tyrone County Councils. As late as mid 1922 these councils were still giving their allegiance to the new Irish Free State government in Dublin.[6]

There was a real danger that these strategically important areas would secede to the south. In the words of one unionist politician, ‘unless something is done now, it is only a matter of time until Derry passes into the hands of Nationalists and Sinn Fein parties for all time’.[7]

Everything changed however, when power was devolved to the new unionist government at Stormont in late 1921. In the local elections of 1924, it redrew the electoral boundaries of Derry city and of counties Fermanagh and Tyrone (among others) and also re-introduced the first-past the post-system of voting, so that a minority of unionist voters now had a majority in a larger number of wards and thus elected more representatives than nationalists.

And thus, Derry city, which had 10,000 nationalist voters versus 7,500 unionist voters, still elected 12 unionist councillors compared to 8 nationalists, giving the unionists a safe majority on the city council or Corporation for nearly 50 years.

It was a similar story in Tyrone and Fermanagh. To cite just one example of many, in the district of Omagh, boundaries were drawn so that even though nationalists had 61% of the votes, local elections returned 18 nationalists to 21 unionists.[8]

In all, after the ‘gerrymandering’ of electoral boundaries, unionists were left in control of 62 out of 73 local government bodies, compared to 49 out of 73 in 1920.[9]

This had knock-on effects on discrimination as it gave unionists almost exclusive control of public jobs and housing. The jobs they naturally gave primarily to their own supporters so that for instance in Derry, where 60 per cent of the population was Catholic they held only 30% of the public sector jobs[10]. The housing issue was an even greater grievance. There was an overall shortage of public housing in Northern Ireland after 1945 due to a growing population. But what made the issue politically explosive was that if Catholics were housed outside the electoral wards they had been confined to after 1924, it would immediately threaten unionist political dominance.

There were thus egregious cases of Catholics being denied social housing. In Dungannon in County Tyrone in 1968, two large Catholic families were passed over in the allocation of a house in preference to a single 19 year old Protestant young woman who worked for a local unionist politician.[11] Similarly in Derry, the Housing Action campaign, also in 1968, drew attention to the case of Catholic family, one whose children had tuberculosis, living in caravan in the Brandywell area, who had been told they had ‘no chance’ of being awarded a house by local government.[12]

It should come as no surprise, then, that the initial impetus for the Civil Rights movement was all west of the River Bann, the symbolic centre of Northern Ireland, particularly in Derry and Dungannon and that protests at housing allocation were the central issue involved.

What is interesting, however, is that few of these issues directly affected Belfast – Northern Ireland’s capital and the city that was to be the worst affected by political violence in the three decades after the late 1960s. In Belfast, there was, in the first five decades of Northern Ireland’s existence, no threat to unionist political or demographic dominance (though that has changed in more recent times). And as a result there was no need to gerrymander electoral constituencies, nor to deny Catholics public housing on a large scale.

In fact very large public housing estates were built in nationalist West Belfast after 1945, notably in the Ballymurphy, Andersontown and Springfield areas among others. In Belfast, where most housing was allocated by the non-partisan Northern Ireland Housing Trust, rather than local government, there was even an attempt to build social housing that was religiously mixed and non-sectarian. Catholics, who tended to be poorer, were actually over-represented there in public housing.[13]

There was little Civil Rights agitation in Belfast around control of local government or housing as a result. While Republicans, including the young Gerry Adams, did campaign around housing in Belfast in the late 1960s, they complained about the quality of the housing being built and the slow pace of slum clearance, but did not allege that Catholics faced discrimination in its allocation.[14]

Unionists are therefore not entirely wrong to say that discrimination in electoral boundaries and housing was geographically limited. But claims that this discrimination was unimportant or that it affected Protestants as much as Catholics are incorrect; control of local government was used systematically in west Ulster to discriminate against Catholics and nationalists.

A second, often repeated demand of the Civil Rights movement was the slogan of ‘one man one vote’. This was, in reality, more important as a slogan than as a political demand. Northern Ireland did largely have one person one vote (women too had the vote after 1918) in elections to the Westminster (British) and Stormont (Northern Ireland) Parliaments. The exception was the continued existence of two university seats at Stormont, which were elected by graduates of Queens University Belfast and plural votes for some business owners.[15]

Again, the main issue in this regard was in local government where only rate (local tax) payers had the vote and owners of businesses had a many votes as they owned properties. Thus unionists who were wealthier, had a disproportionate share of voters and thus control over local government. While not insignificant, however, the rate payers’ franchise did not by itself give unionist an electoral majority anywhere; that was achieved by other means, mainly by gerrymandering electoral boundaries.

The third major area of discrimination alleged was in employment. As we have seen, this was particularly pronounced in western Northern Ireland, where unionists were a demographic minority but still controlled most organs of local government. In Newry, in the south west of Northern Ireland, one of the few nationalist controlled councils, the discrimination went the other way, where very few of public jobs were allocate to Protestants.[16] In Northern Ireland as whole, however, Catholics comprised about 30% of public sector employees, which was largely in line with their share of the population.

Systematic discrimination was far more pronounced in the west of Northern Ireland, where unionists were in a minority.

From this we might conclude that discrimination was largely a feature of border areas where unionists (and nationalists in the case of Newry) used public employment to maintain political control.

However, this masks a deeper picture of more widespread discrimination. While Catholics may have been proportionately represented in manual grades of public employment, in senior positions they were woefully underrepresented, at only 11%.[17] In the civil service, the imbalance was even more pronounced, here Catholics comprised only 5-7% of higher grade employees and only 6 out of 68 judges were Catholics.[18]

In the police force, the RUC, only around 10-15% of constables were Catholics and in the reserve, armed police force, the Ulster Special Constabulary or B Specials, they were virtually non-existent.

Unionists alleged that this was due to Catholics’ lack of identification with the state or lack of sufficient education for these positions. These factors might be plausible to a degree but not to the extent to which the disparity existed. Catholics increasingly availed of free second and third level education after they were introduced by British Labour governments after 1945, but their representation in senior public jobs did not markedly increase. One Catholic secondary school principle told the story of how he had stopped sending high achieving students to the Northern Ireland Civil Service examinations after not one candidate was accepted over a period of several years.[19]

Like housing west of the Bann, this discrimination was largely political in intent; unionists were determined not to lose their grip on ‘their’ state. But its results were also social, making Catholics disproportionately likely to be unemployed or poor in Northern Ireland.

Finally, the remaining key demand of the Civil Rights movement was the abolition of the Special Powers Act. This piece of emergency legislation, first passed in 1922 and made permanent in 1933, allowed for the internment without trial and flogging of suspects who were deemed to have broken the regulations of the Act as defined by the Minister for Home Affairs. The minister was also entitled to ban organisations – such as the Irish Republican Army or the political party Sinn Fein and to proscribe public meetings or marches.[20]

Nationalists alleged that this legislation amounted to a grievous violation of the rights of free speech and free assembly and that it was directed almost entirely against their community.

In one sense, this was an overstatement, as the southern Irish state also had its emergency legislation – the Public Safety Acts of 1922, 1923, 1927 and 1931 and the Offences against the State Acts since 1939 – that were in some respects more draconian than their Northern counterpart. In the Free State, those who used arms against state forces could not only be interned but also executed. Eighty one republicans were executed by firing squad in the Civil War of 1922-23 under the Public Safety Act and another five under the Offenses against the State Act during the Second World War. In the North, only republican, Tom Williams in 1943, had been executed since partition, and he, not under emergency legislation but after a trial by jury, for killing a policeman.[21]

Where the North was different, however, was that emergency legislation was overwhelmingly used against one section of the community, even though illegal violence also came from loyalist paramilitaries. In the 1920s, for instance, Northern Ireland interned about 700 Republicans, but only about a dozen loyalists and the latter only after the IRA threat had been crushed by mid 1922.[22] Another 400 republicans were interned without trial between 1956 and 1961 during the IRA Border campaign.[23]

The Northern Ireland government did also proscribe the loyalist Ulster Volunteer Force (UVF), when it appeared in 1966 and began murdering Catholics. However whereas nationalist marches and demonstrations were routinely forbidden, this was only done of the rarest of occasions with Orange Order or loyalist marches. [24]

The perception therefore was that the unionist government was willing to turn a blind eye to loyalist violence when it was useful, whereas it used the Special Powers Act to ban legitimate nationalist political activity as well as republican paramilitaries.

Provocation?

One of the more tedious arguments about the Civil Rights movement as it coalesced in 1966-68 was whether it was in reality a front for the IRA.

The IRA through the ‘Wolfe Tone Clubs’ was indeed involved in the founding of the Northern Ireland Civil Rights Association in 1966, as part of its pivot towards civic agitation and left wing politics after the failure of its Border Campaign in the 1950s, but it was far from the only group to take part, nor did it control the organisation.

The impetus for the first major civil rights marches came from others; in Dungannon from the old Nationalist Party, notably Austin Currie and in Derry from left wing Northern Ireland Labour Party members such as Eamon McCann and others as well as local republicans. In Derry, indeed, after the initial disturbances, the movement was largely taken over by more conservative nationalists such as John Hume and Paddy Doherty. The organisation that marched from Belfast to Derry in early 1969, People’s Democracy, was mainly made up of students from Queens University Belfast such as Bernadette Devlin and Michael Farrell.

Unionists alleged that civil rights activists deliberately provoked violence.

So the contention, made loudly at the time by Ian Paisley and his followers, that the Civil Rights movement was a cover for the IRA, was wrong. Republicans were involved, but it was a broad based movement among Northern nationalists, particularly in the west of Northern Ireland.

However, there are other arguments against the Civil Rights movement that have a little more weight. One is that it deliberately set out to provoke the unionist authorities into an overreaction and to cause violence. While many Civil Rights marches were perfectly peaceful, this allegation, to some extent, is true. As Eamon McCann himself admitted, ‘we had indeed set out to make the police over-react. But we hadn’t expected the animal brutality of the RUC’.[25]

The Derry activists used direct action to combat what they considered obvious injustices, for example blocking Lecky Road in Derry with a caravan to protest that a family was living in it.[26]

The intention here was to force the authorities to house the family or use force to disperse the protest thus highlighting the injustice. Similarly, when the Derry activists called their first march in the city in October 1968, they chose a route through the city walls into the centre of Derry because they knew it would be banned – as all nationalist marches to the city centre were. Here again, this was provocation of a sort, but not unjustifiably so. Why should nationalists, a majority in Derry, not be allowed to march into and demonstrate in its historic city centre?

What is less easy understand however, is the deliberate routing of some marches through working class Protestant areas where they knew they would antagonise local loyalists.

The Derry march of October 1968 that was eventually baton charged by the RUC, for instance, was planned to start in the Waterside, the working class Protestant stronghold just across the river Foyle from Derry’s city walls.[27] Why march from there and not from the Catholic Bogside area on the other side of the river?

Secondly, the People’s Democracy march from Belfast to Derry in January 1969 again set out to impel reform by destabilising Northern Ireland. A ‘truce’ had been called in late 1968, where the Northern Ireland Prime Minister Terence O’Neill asked for a halt to Civil Rights marches so that he could enact reforms and most of the Civil Rights movement had agreed, particularly as O’Neill also sacked his hardline minister for Home Affairs William Craig. People’s Democracy set out to break this ‘truce’.[28]

They also deliberately took a route through south county Derry that its organiser Michael Farrell, who was from the area, knew would take it through mostly Protestant and staunchly loyalist, villages and towns. As Farrell himself later commented, ‘a lot of the route was through my home area of south Derry, so I knew the likely reaction’.[29] It is not in any way to justify the subsequent loyalist attacks on the marchers at Burntollet and elsewhere – which the RUC failed to prevent – to say that such an outcome was entirely predictable. Why, it must be asked at this distance, not plan a different route unless the intention was to stir up sectarian passions?

It was the rioting arising out the People’s Democracy march that set off serious disturbances in Derry, culminating the deadly riots of August 1969. In these, after rioting had spread to Belfast, loyalists, aided in some cases by the police, attacked Catholic districts. The Provisional Republican movement, which grew out of the rioting, argued that it was only by force that nationalists in Northern Ireland could be defended and only by ‘armed struggle’ and a united Ireland that their demands for equality could be met.

Was Northern Ireland irreformable?

It has often been argued that the Civil Rights agenda was perfectly possible to implement in Northern Ireland as it existed in 1968 and that most of its was indeed implemented by the early 1970s.

Electoral boundaries were redrawn in 1969-1973. Public housing was now to be allocated by an independent body the Housing Executive. One man one vote was fully implemented in 1968 for general elections and the rate payer franchise was abolished in 1973 to be replaced by universal suffrage.

The RUC was temporarily disarmed (it was re-armed in 1971) and the B-Specials stood down, to be replaced by the Ulster Defence Regiment. The Special Powers Act was repealed in 1973, though again it was replaced by other emergency legislation.

It is difficult to see how Northern Ireland could have been successfully reformed in its pre-1968 form without upsetting unionist dominance.

However, all of this took place at a time when the central British government had again, because of the outbreak of political violence, become directly involved in Northern Ireland, whose government it abolished altogether in 1972, reintroducing ‘Direct Rule’ from London until 1998. Since 1972, policymakers have predicated self-government in Northern Ireland as being based on ‘power-sharing’ between nationalists and unionists.

It is difficult to see how such reforms were compatible with a unionist dominated Northern Ireland government such as existed prior to 1968. A Stormont unionist government, had it reformed its local government boundaries and franchise could have seen as much as half its geographical area (though not its population) under nationalist control. It would only have been possibly to find a political solution with some form of power-sharing, something unionist were not willing to concede until late 1990s.

Nor is it easy to see how a unionist government could have sold such reforms to its own supporters. Derry unionist Gregory Campbell has stated that he perceived the Civil Rights campaign to be objectively anti-Protestant since they were ‘demonstrating for rights that I didn’t have’ as a working class unionist and then seeking confrontation with the authorities.[30] This is a little unfair to most of the Civil Rights activists of that era, who pointed out that they were calling for more social housing, more jobs and universal suffrage, for all, including the Protestant working class.[31]

However, due to the nature of Northern Ireland, particularly in its western parts, it is probably true to say that a reformed Derry Corporation for instance, with a nationalist majority, would inevitably have transferred scarce resources to its supporters at the expense of poorer unionists.

This partly explains the fierce reaction of working class loyalists to the Civil Rights movement and the outbreak of the Troubles in 1969. The cycle of violence initiated in 1969 did not blow out until the ceasefires of 1994. It also makes one wonder whether Northern Ireland, as it was formed in 1968 could ever have been reformed peacefully.

To say this is not to endorse the Provisional Republican argument that ‘armed struggle’ was the only alternative – that too failed according to its own lights, that is to abolish Northern Ireland and to achieve a united Ireland – and then at considerable cost in lives. But it is to say that Northern Ireland was from its creation an inherently unstable entity, because it enforced the political domination of one community over the other as the basis for its political system.

References

[1] For an overview account of the movement for Civil Rights agitation and its descent into violence in 1968-69, see David McIttrick, David McVea, Making Sense of the Troubles, A History of the Northern Ireland Conflict, (2012), p.47-56

[2] Richard English, Terrorism, How to Respond, (2009) p.65.

[3] Reported in Irish News 12 October 2018 https://www.irishnews.com/news/2018/10/13/news/stormont-discrimination-of-catholics-hugely-exaggerated-says-david-trimble-s-ex-aide-1457251/

[4] Newsletter 5 October 2018 https://www.newsletter.co.uk/news/gregory-campbell-working-class-protestants-feared-what-civil-rights-movement-would-become-1-8657612

[5] John Whyte, ‘How much discrimination was there under the Unionist regime, 1921-1968?’, http://cain.ulst.ac.uk/issues/discrimination/whyte.htm#chap1

[6] Eamon McCann, War and an Irish Town, (1993) p.217-218. See full results here https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/1920_Irish_local_elections

[7] David McIttrick, David McVea, Making Sense of the Troubles, A History of the Northern Ireland Conflict, (2012), p.9

[8] See McCann, War and Irish Town, p.240-41, McKittrick, McVea, Making Sense of the Troubles, p.9-10

[9] Whyte, ‘How Much Discriminations Was there Under the Unionist Regime?’ To further underline the lack of nationalist political representation, five of the eleven nationalist controlled councils were in the Newry area of south County Down.

[10] Whyte, ‘How Much Discrimination’

[11] McKittrick, McVea, Making Sense of the Troubles, p.46-47

[12] McCann, War and an Irish Town, p.89

[13] Whyte, ‘How Much Discrimination’.

[14] See for instance Adams’ account of the West Belfast Housing Action Committee in Free Ireland: Towards a Lasting Peace, p.10-12

[15] For an overview, see here http://cain.ulst.ac.uk/issues/politics/election/electoralsystem.htm

[16] Whyte, ‘How Much Discrimination’

[17] Whyte, ‘How Much Discrimination’

[18] Whyte, ‘How Much Discrimination’ See also Simon Prince, Northern Ireland’s 1968, (2018) p.80-81.

[19] Prince, Northern Ireland’s 1968, p.82

[20] The Special Powers Act in full is online here The Special Powers Act

[21] See Brian Hanley, The IRA A Documentary History pp.51, 108-110. Though Hanley cites the canonical republican figure 77 executions in the Civil War, it since been determined that there were 81.

[22] Michael C Rast, The Mad Dance OF Death The Ulster Protestant Association, 1922 https://www.theirishstory.com/2016/02/15/the-mad-dance-of-death-the-ulster-protestant-association-in-belfast-1921-22/#.XARUSzGYTIU

[23] Brian Hanley, Scott Millar, The Lost Revolution, p.17-18

[24] Whyte ‘How Much Discrimination’

[25] McCann, War and an Irish Town, p.99

[26] McCann, p.89

[27] McCann p.93

[28] Prince, Northern Ireland’s 1968, pp.190-194, 207-209

[29] Prince, Northern Ireland’s 1968, p.209

[30] Newsletter 5 October 2018 https://www.newsletter.co.uk/news/gregory-campbell-working-class-protestants-feared-what-civil-rights-movement-would-become-1-8657612

[31] Prince, Northern Ireland’s 1968, p.115