‘A Declaration of War on the Irish People’ The Conscription Crisis of 1918

How the attempt to impose conscription on Ireland was defeated in 1918. By John Dorney.

How the attempt to impose conscription on Ireland was defeated in 1918. By John Dorney.

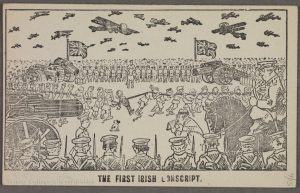

In April 1918, the British government of David Lloyd George tried to extend conscription to Ireland. The policy, logical though it may have seemed during a crisis point in the Great War, was a disaster.

Irish self-government, or Home Rule, promised since 1912, had never materialised. The Rising of Easter 1916 and the British reaction to it had sent shockwaves through nationalist Ireland.

The mass mobilisation of the spring of 1918 in the end not only defeated conscription, but paved the way for the end of British rule in most of Ireland.

Now, when asked to contribute hundreds of thousands of unwilling young men to fight and die for the Empire, Ireland, by and large, refused.

The conscription crisis united a mass movement that included not only the separatists of Sinn Fein, but also the moderate Irish Parliamentary Party, the labour movement and the Catholic Church. The mass mobilisation of the spring of 1918 in the end not only defeated conscription, but paved the way for the end of British rule in most of Ireland.

War enthusiasm

It was all a far cry from 1914, when Great Britain first went to war with the German Empire. Then, moderate Irish nationalist opinion was on the whole, supportive of the war. Germany had, after all invaded Belgium, a small Catholic country, and in the first months of the war, treated Belgian civilians quite ruthlessly.

It was all a far cry from 1914, when Great Britain first went to war with the German Empire. Then, moderate Irish nationalist opinion was on the whole, supportive of the war. Germany had, after all invaded Belgium, a small Catholic country, and in the first months of the war, treated Belgian civilians quite ruthlessly.

The ‘sack of Louvain’ in particular aroused much indignation in Ireland. Some Irish nationalist, such as the Irish Party’s rising intellectual star Tom Kettle sincerely saw the war as a struggle for European civilisation against ‘barbarism’.[1]

In 1914 , moderate Irish nationalist opinion was on the whole, supportive of the war.

John Redmond, the leader of the Irish Parliamentary Party famously called on his supporters to join the British Army, both ‘in defence of right, morality and religion’ and also in the hope that a grateful British government would then grant Home Rule.

‘The interests of Ireland, of the whole of Ireland, are at stake in this war. This war is undertaken in the defence of the highest principles of religion and morality and right, and it would be a disgrace forever to our country, and a reproach to her manhood, and a denial of the lessons of our history, if young Ireland confined her efforts to remaining at home to defend the shores of Ireland from an unlikely invasion… go wherever the firing line extends’.[2]

He envisaged the Irish Divisions as a sort of proto-Irish Army. And initially, the response in Ireland was positive. Over 200,000 young Irishmen served in the war, of whom about 150,000 volunteered during the conflict itself. [3]

Redmond himself thought that war service could actually heal some of the divisions in Ireland – between nationalist and unionist, Catholic and Protestant and upper and lower class. They ‘will be fighting shoulder-to-shoulder with nationalists in the trenches in France. In God’s name, let us try to grasp from the situation the real unity of Irish people.’[4]

Even though Ireland was embroiled in a political crisis over Home Rule and even though, just months previously, the British Army had fired on a civilian crowd at Bachelor’s Walk in Dublin, killing three, British troops leaving Ireland for the war front general got a warm send off.

The (admittedly unionist) Irish Times reported,

“The scenes in Dublin during the embarkation cannot fail to have been cheering and encouraging to the gallant soldiers…From the early hours of the morning large crowds assembled on the quays to cheer the troops on their way and to wish them God-speed on their adventure. The main thoroughfares through which the troops passed were lined with spectators and on all sides indications were given of popular sympathy and goodwill.”[5]

‘To hell with the British Empire’.

However, this was never the full story. Pre-war political divisions remained and support for the war effort in Ireland was never universal.

While Catholics and Protestant did indeed serve together in the trenches of France, Flanders, Gallipoli and elsewhere, Protestants were over represented. Moreover there was a strong concentration of recruits from the urban working class, from which the British Army had always recruited, whereas farmer’s sons were notable by their absence.

Predictably, one source of virulent opposition came from the separatists of the Irish Republican Brotherhood, who were incensed that Redmond had committed the Irish Volunteers, the militia brought into being to ensure Home Rule, to the British war effort.

‘To hell with England! Let her fight her own battles’. Sean McDermott, 1914.

Leading IRB member Sean McDermott told a crowd in Tipperary in 1914, “The Volunteers were not brought into existence to fight for England. To hell with England! Let her fight her own battles. The Volunteers are only intended to fight for Ireland!”[6]

While the IRB newspaper Irish Freedom asked if Redmond was a, ‘madman or traitor?’ for, ‘conspiring with those whose aim is to remove Ireland from the roll of nations’. It concluded that his pro-war policy was, ‘either incredible stupidity or damnable treachery’. For separatists it pledged, “Hatred to the Empire and Remember Bachelor’s Walk!”[7]

But the separatists were not the only source of opposition to the war. Even at this early stage, it is possible to discern dissent from two other crucial sources, the labour movement and the Catholic Church.

The Irish Transport and General Workers Union or ITGWU had been founded in 1911 by James Larkin and had from the start had both a nationalist and socialist bent.

In Sligo in September 1914, Thomas Scanlan an IPP Member of Partliament spoke in favour of Home Rule and of the war effort: ‘Ireland is now and shall for all times be a nation once again…but this same Statute binds Ireland indissolubly to the British Empire. A group of labour activists from the ITGWU heckled him with, ‘To hell with the Empire’ and meeting broke up with what the local paper called, ‘a spirited bout of fisticuffs’.[8]

James Connolly, the leader of the union from 1914 until his execution in 1916, for his part in the Easter Rising, wrote that workers all of over Europe should have called a general strike against the War:

‘I believe that the socialist proletariat of Europe in all the belligerent countries ought to have refused to march against their brothers across the frontiers, and that such refusal would have prevented the war and all its horrors even though it might have led to civil war … ; as workers, they were indeed in control of the forces of production and distribution, and by exercising that control over the transport service could have made the war impossible.. [9]

The idea of a general strike against the war would eventually be prophetic in Ireland.

A third, perhaps surprising, source of anti-war opinion came from the Catholic Church. In November 1915, 700 Irishmen trying to emigrate to the US were blocked at Liverpool on the basis that they should be in the Army. John Redmond said that it was ‘very cowardly of them to emigrate’ rather than enlist. To which Bishop Edmund O’Dwyer, of Limerick retorted in public, ‘Their crime is that they are not ready to fight for England. Why should they? What have they or their forbears ever got from England that they should die for her?’.[10]

Losses and decline in recruitment

However, as yet these voices were in a minority.What seems to have caused a steep drop in Irish recruitment was the mass casualties Irish units suffered in the first two years of the war.

The 10th Irish Division suffered grievous losses at Gallipoli in 1915, while the 16th and 36th (the latter Ulster) Divisions took terrible casualties in 1915 and especially on the Somme in 1916.

Some 44,000 Irishmen enlisted in 1914 and 45,000 followed in 1915, but this dropped to 19,000 in 1916 and 14,000 in 1917.[11]

Irish recruitment fell off rapidly when Irish units began to take mass casualties in 1915.

In addition, there was a perception in nationalist Ireland that their contribution was not appreciated. Redmond’s idea of Irish Division officered by Irish officers had not come to pass – Irish nationalist were still considered too suspect – whereas the predominantly Ulster unionist 36th Division, generally was led by ‘its own’ officers. It is possible also that economic recruitment had reached its ceiling by this point.

It should not surprise us at all that growing awareness of the lethality of the Great War stymied voluntary recruitment. The same was true in Britain itself, which prompted the Government of Asquith to introduce the Military Service Act in January 1916 bringing in compulsory military service in England, Scotland and Wales.

This was not yet, in 1916, extended to Ireland. For one thing, John Redmond appealed to the government not to do so, aware that is was unpopular. For another, Augustine Birrell and Matthew Nathan, the senior British officials in Ireland, made it their priority not to provoke nationalists – seeing their role as overseeing a peaceful transition to Home Rule.

It became even more difficult for administration to envisage the orderly implementation of conscription after the Rising of 1916, which gave the youth a very different idea of ‘fighting for Ireland’ also played a role, as did outrage at the British execution of the Rising’s leaders and wholesale arrests of suspects in its aftermath.

Birrel and Nathan lost their jobs as a result of the Rising, but their successors were equally cautious. Henry Duke, the Chief Secretary for Ireland from 1916-18, wrote, very presciently, to his superiors, that extending conscription to Ireland, especially if Home Rule were not enacted first, would, ‘consolidate into one mass of antagonism all the Nationalist elements in Ireland, politicians, priests, men and women’. [12]

Similarly the Inspector General (commander of the Royal Irish Constabulary or RIC) Joseph Byrne, though that in Ireland compulsory military service ‘can be enforced with the greatest difficulty’. [13]

New forces: Sinn Fein and labour

This difficulty would only increase as the war sent on. After the Easter Rising of April 1916, with its overt military challenge to British rule, with the British execution of the Rising’s leaders and mass arrest of suspects, latent opposition to the British war effort began to coalesce into something more solid.

Though the Rising was initially met with incomprehension and quite a lot of hostility among the general Irish public, attitudes began to shift quite quickly after it.

British repression was harsh enough to spark a sense of outrage, but not harsh enough to terrorise the population into compliance. Most of the insurgent prisoners were released by the Christmas of 1916 and the rest, including the surviving leaders, were released the following summer.

By 1917, a combination of discontent with the war, disappointment at the failure to deliver Home Rule and anger at the repression of the Easter Rising was driving the rise of new political forces in Ireland,

The Rising veterans regrouped both in the Volunteers and in the separatist political party Sinn Fein, headed by Rising veteran Eamon de Valera, which suddenly began to win elections – three by-elections in 1917. Sinn Fein explicitly campaigned on the basis that they would not attend the British parliament and that if they secured a majority in Ireland, would unilaterally declare independence.

By the close of 1917, they also had fresh martyrs, the most high profile being Republican leader Thomas Ashe died as a result of force feeding while on hunger strike in Mountjoy Prison in September of that year.[14]

But Sinn Fein was not only rising force in the land. Also rebuilding its strength was the Irish labour movement. Like the republicans, the labour movement had taken some hard knocks. Firstly the Transport Union (ITGWU) had fared disastrously in the great Lockout of 1913, haemorrhaging members and funds.

Then in 1916, though only the Citizen Army, a militia formed to defend strikers in 1913, took part in the Eater insurrection, it too had hit the unions hard. James Connolly the leading ideological light of the movement, had been executed, the ITGWU’s headquarters at Liberty Hall wrecked and many activists, including ITWGU leading figures William O’Brien and PT Daly, were arrested and interned. Richard O’Carroll the general secretary of the bricklayers’ union was also killed in the Rising. [15]

However, the labour movement and in particular the ITGWU also experienced a resurgence in the following two years, growing from a post-Lockout low of some 5,000 members to over 60,000 by 1918. Partly this was the result of the release of activists such as O’Brien. However the rush into the unions was, essentially a defensive reaction to wartime inflation, trying to bring wages up to the level of rising food prices. The subsequent strike-wave, which saw 120 disputes in 1917 and 200 every year from 1918 1920 should be understood in these terms.[16]

Nevertheless, organised labour was now a serious political force. And it too positioned itself against conscription and for an end to the war. The Irish Trade Union Congress in Derry August 1917, resolved for peace without indemnities (i.e. without war reparations for either side), by 64 votes to 24 – the dissenters were mostly northern unionists and unanimously resolved against the proposed partition of Ireland.[17]

By this point the Catholic Church had also turned against the war, with Pope Benedict XV calling the conflict ‘futile’ and calling on Christians to make peace. In Ireland, Bishop O’Dwyer wrote that ‘prolongation of this war for one hour beyond what is necessary is a crime against God and humanity.’[18]

As yet though, the disparate voices against the war in Ireland had not come together.

The German Spring Offensive of 1918

What changed everything, and forced the British government’s hand with regards to conscription in Ireland, was the German spring offensive on the Western Front in 1918.

This was last-gasp attempt to win the war before American reinforcements arrived to bolster the British and the French and to give the Entente powers an overwhelming numerical and material advantage. Initially the Germans made rapid gains, threatening Paris and opening the prospect of splitting the British and French armies.

In Britain itself, plans were made to call up men aged up to 48 years old for military service. It must have seemed logical for David Lloyd George, the new prime minister, to tap the pool of available young men in Ireland. Very much against the advice of the British administration in Ireland itself, at this crisis point of the war for Britain, conscription was extended to Ireland.

The German Spring Offensive of 1918 created a crisis for Britain on the western front and force Lloyd George’s government to extend conscription to Ireland.

On April 16, 1918, the Westminster Parliament extended the Military Service Bill to Ireland. Lloyd George was determined to push the bill through, shrugging off opposition by noting that during the American Civil War Abraham Lincoln had also had to fight impose the draft to preserve the Union. Lloyd George, it was implied would do the same. [19]

In order to impose conscription in Ireland, the reluctant Henry Duke, the Chief Secretary for Ireland, was by-passed, eventually to be replaced in May 1918 by Edward Shortt. In the short term however, Lloyd George appointed a general, Sir John French, commander of the British Expeditionary Force in France in 1914, as Lord Lieutenant of Ireland, a posting he interpreted as ‘a quasi-military government’ in Ireland to impose conscription.[20]

French thought that there would be ‘disturbances’ but was confident he could overcome them. He planned to use air power, located at ‘advanced bases’ to ‘play about with either bombs or machine guns’ on those who opposed conscription.[21]

It was hoped to gain about 160,000 recruits in Ireland, a wildly optimistic total given that in four years only about 150,000 men had volunteered.

Opposition

The Irish Parliamentary Party, who had always argued that it was by working inside the British system that Irish demands could be fulfilled, were suddenly made to look impotent. For all of its avowed loyalty and support of the war effort, for all of its pleas and back door negotiating, conscription had come to Ireland anyway.

John Redmond had died in early 1918 and leadership of the party was taken over by the markedly less pro-British John Dillon. But even though the IPP withdrew from Westminster in protest at conscription and its leader John Dillon shared platforms with Eamon de Valera, it was Sinn Féin, the party that advocated Irish independence and armed resistance who led the way.

Even some Irish Party members who had followed John Redmond and joined up for the War were turned into separatists by the conscription crisis. Daniel Sheehan, for example, an Irish Party MP and Captain in the British Army, told the House of Commons that everything he had signed up for in 1914 had been a fraud.

The conscription crisis brought separatist rhetoric, of ‘English tyranny’ and military occupation and the obligation of national resistance, into the mainstream

‘You state that you are fighting for justice, freedom and liberty. It was in the belief this country was fighting for those principles that I and others offered our services in the earlier months of the War. I ask what freedom, what justice, or what liberty is the Irish conscript going to get?’

He raged that, contrary to the promises made to Redmond in 1914, there was no Irish legislature, and no Irish units led by Irish officers:

The officers were a horde of English Cockneys… A similar pledge was given in the case of Carson’s army, and it was observed; but it was not observed in the case of the Irish Brigade…. I tell you that you may take our men at the point of a bayonet – you will not get them in any other way, but you will not succeed in killing the spirit of Irish nationality, and at the end you will find you have lit a flame which is not likely to die out in our generation.

He raged also about the repression of the Easter Rising:

You have not trusted Irishmen. You have not dealt fairly with them since this war broke out. You have heaped insults and humiliations upon them… I remember reading with horror what I regarded as a butchery of a Labour leader [James Connolly] in Dublin in Easter Week. Although he was not able to stand up to be shot, although he was wounded, if he had been a soldier serving in any other part of the world he would have received the honour due to a soldier, but he was brutally butchered, maimed and mangled. You are teaching us once again that we cannot trust you, and that if we are to exist as a nation we must fight for our nationality… That is a right which we Irishmen are asserting for our people, and if need should arise, we will be ready to seal it with our blood’.[22]

That such rhetoric could come from a Member of Parliament and serving British Army officer was extraordinary. The conscription crisis had brought separatist rhetoric, of English tyranny and military occupation and the obligation of national resistance – all of which had seemed outlandish to moderate nationalists in 1910 – into the mainstream. The Irish Party was suddenly irrelevant.

The Catholic Bishops issued a statement thundering, ‘the attempt to force conscription upon Ireland against the will of the Irish people and in defiance of the protests of its leaders’ [is] an oppressive and inhuman law which the Irish people have the right to resist by all the means consonant with the law of God.’[23]

But it was the separatists of Sinn Fein who led the anti-conscription campaign. Eamon de Valera, addressing a meeting in Dublin, made the case not only against conscription but against British rule in Ireland: ‘We deny the right of the British government or any other external authority to impose compulsory military service in Ireland against the expressed will of the Irish people… The passing of the Conscription Bill by the British House of Commons must be regarded as a declaration of War on the Irish people.’[24]

It was they who drafted an anti-conscription pledge that they the Irish Party and the Labour Party presented to the public at Dublin’s Mansion House on April 18 1918, which the following Sunday (often at Church gates after Mass) was signed by hundreds of thousands of people.

As well as mass passive resistance the Volunteers planned ‘ruthless warfare’ including the killing of all government officials, should conscription be enforced.

The nationalist militia, the Volunteers, who saw their numbers swell from less than 10,000 to over 100,000, drew up plans for a new insurrection should conscription be introduced. Every police station was to be seized and its arms taken, every road was to be blocked and communications severed. Anyone siding with or representing the government was to be shot. So argued Ernest Blythe in a pamphlet titled Ruthless Warfare.[25]

In Kerry, where he had returned after imprisonment, he told his company of Volunteers ‘about the necessity of fighting with whatever weapons were available if an attempt were made to apply conscription, and said it was better to die fighting for our freedom and for Ireland than to be led out like dogs on a chain to die for England on the Continent.’[26]

Volunteer Laurence Nugent recalled’ Had the British attempted to impose conscription there would have been great slaughter, as every man of military age would have fought with every means at his disposal and the women would have made a good showing in the fight’.[27]

The Volunteer Executive also hatched a plan, in which a squad of gunmen, led by Cathal Brugha, would gun down the front benches of the British government in the Westminster Parliament should the order to impose conscription be given.

Cumann na mBan, the Republican women’s movement, also called a day of protest, Lá na mBan (‘The Day of Women’) in which they urged women not to take the jobs of men conscripted for the army.

General Strike

However it the end it was not petitions, nor the threat of force, that defeated conscription. That the Volunteers would have resisted by force we need not doubt, but they were almost without arms after the 1916 Rising. What was decisive was rather a general strike, that brought the country to a standstill on April 23 1918, that defeated conscription.

An emergency Trade Union conference was called for April 20, 1918 on conscription at which the delegates voted, much as James Connolly had recommended in 1914, for a general strike. April 23 and £1000 was withdrawn from Congress strike funds.

What finally defeated conscription was the general strike April 23, 1918.

The cause seems to have been popularly taken up. In the case, for example, of the Bricklayers’ union or AGIBSTU [28] the members of the union resolved unanimously to comply with its call to abstain from work on 23 April and to institute a special levy for ‘defence purposes.’ On Tuesday 23 April all members of the bricklayers’ union duly ceased work in Dublin, and all around the country. Three hundred members attended the union headquarters at Cuffe Street to sign the anti-conscription pledge. The one man who did go to work that day was ‘fined severely’.[29]

While the Bricklayers were a small craft union, large unions were involved; the: the largest, the ITGWU, had 40,000 members, the Railway union 20,000 more. Almost everywhere, the country lurched to a halt; transport, even the munitions factories set up for the war, ceased work for the day. As it happened, such was the popular support for the strike that many employers paid workers for the day and the strike funds pooled were not needed.[30]

Laurence Nugent recalled: ‘On April 23rd labour declared a one day strike as a protest against conscription and business of all descriptions was completely suspended. The Post Offices and schools were closed.[31]

In Dublin, there was no march or demonstration because the strike fell almost on the second anniversary to the day of the outbreak of the Easter Rising and all meetings had been banned, but major demonstrations took place in Limerick, Sligo and Cork on the day of the general strike.

The one exception was Belfast, where many workers were unionists and many trade unionists refused to participate.[32] In the event though Thomas Johnson did address an anti-conscription meeting of 3,000 at City Hall in Belfast against conscription, in which he told his listeners;

‘The Irish Labour Movement now stands as the bulwark of free democracy in Western Europe. We are resolved to fight for the freedom of the working classes of Ireland and we are also fighting for the freedom of the working classes of England.’[33]

Even the British Labour Party voiced its opposition to the imposition of conscription on Ireland. [34]

The British back down: The Hay Plan and the German Plot

The general strike was a one day protest but it demonstrate the inability of the British government to impose conscription. With the prospect of no transport running or essential services operating, not to mention determined resistance from the populace, a huge number of troops would have to be withdrawn from the fronts to secure an unspecified number of recruits of dubious loyalty to the British cause.

In the aftermath of the general strike the British government quietly back down and conscription was never imposed on Ireland.

In the end the government quietly went along with Henry Dukes pessimistic view that, ‘We might almost as well as well recruit Germans’ as attempt to impose conscription in Ireland and plans to enforce it were shelved’[35]

There was brief and somewhat eccentric plan, thought up by a British officer named Stuart Hay, and taken up briefly by the new Chief Secretary Edward Shortt, to induce Irishmen to recruit instead for the French army, or at least labour battalions in French service, with the blessing of the Catholic Church. Although some churchmen such as Cardinal Logue, a long-time opponent of Irish republicans, showed some interest, nothing of substance came of it.[36]

By the summer of 1918 in any case the dire crisis of the British and French on the western front had eased. The German spring offensive had stalled and American troops had begun arriving at the front in large numbers. The urgent need for more recruitment in Ireland was over.

However the confrontation between the British state in Ireland and the separatists was only beginning. In the aftermath of the conscription crisis public fairs and sporting events were temporarily banned to prevent seditious public meetings, Sinn Fein, Gaelic League and Cumann na mBan meetings were declared illegal and 13 counties were ‘proclaimed’ or put under a kind of military rule.[37]

In May 1918, alleging a ‘German plot’ between the ‘Sinn Feiners’ and their enemies in Europe, the British issued arrest warrants for hundreds of leading separatists. While there had been contacts between the Germans and Irish republicans since Easter 1916, the charge was essentially an excuse to round up militant leaders after the mass protests against conscription.

Edward Shortt, the new Chief Secretary, all but admitted as much, “we do not pretend that each individual has been in personal active communication with German agents, but we know that someone has.” Some 70 suspects, including Eamon de Valera, were arrested and imprisoned.[38]

Aftermath

The conscription crisis of 1918 was a crucial turning point in twentieth century Irish history – as important, as the Rising of Easter 1916, if not more so. It was the anti-conscription campaign that made the Volunteers (as of 1919, the IRA) and Sinn Fein into mass movements. It also showed the political power of the labour movement and how it could be mobilised to nationalist ends. And in showed them that the Catholic Church, traditionally an enemy of Irish Republicanism, might not be an ally, or at least a tacit supporter.

The conscription crisis made the British look cruel but weak in Ireland, a highly dangerous position for any government.

Moreover, it left British legitimacy in Ireland in ruins. It had brought to a head the discontent over the postponement of Home Rule since 1912 – by the end of the war it still seemed no closer – and stretched to breaking point any feelings of loyalty the majority in Ireland had to the British Empire. It had totally undermined John Redmond’s vision of a loyal, contented, self-governing Ireland within the United Kingdom.

The British were now perceived by separatists and their supporters as cruel and arbitrary, but, more importantly, beatable. Put enough pressure on them, the conscription crisis showed, and they would bend.

It should not be imagined that the conscription crisis turned everyone in Ireland against the war. Thousands, both north and south still supported their relatives in British uniform by the time of the Armistice in November 1918.

But there is no doubt at all that the conscription crisis also laid the way open for the victory of Sinn Fein in the general election of December 1918 and ultimately to the declaration of Irish independence.

References

[1] Joseph Connell, History Ireland, Emmet Dalton, Tom Kettle and the Battle of the Somme. https://www.historyireland.com/volume-24/countdown-2016-emmet-dalton-tom-kettle-battle-somme/

[2] John Redmond’s famous speech at Woodenbridge in September 1914, Reprinted in History Ireland here, with article by Joseph Connell. https://www.historyireland.com/volume-22/john-redmonds-woodenbridge-speech/

[3] David Fitzpatrick, ‘Militarism in Ireland’ in Thomas Bartlet, ed. A Military History of Ireland, p.388

[4] http://www.rte.ie/centuryireland/index.php/articles/redmond-irish-nationalists-will-bear-burden-on-behalf-of-empire

[5]Irish Times, August 22,1914

[6] Gerard MacAtsaney, Sean MacDiarmada, The Mind of the Revolution, p 74

[7] Irish Freedom, September and October 1914

[8] Michael Farry, The Irish Revolution, Sligo, p.22

[9] James Connolly, Revolutionary Unionism and War, International Socialist Review, March 1915.

[10] Charles Townshend, Easter Rising, 1916 p.79

[11] Fitzpatrick, ‘Militarism in Ireland’ in A Military History of Ireland, p.388

[12] Charles Townshend the Republic, The Fight for Irish Independence, p10

[13] Charles Townshend the Republic, The Fight for Irish Independence, p10

[14] Listen to Tomas MacConnmara explain the background to the hunger strike here https://www.theirishstory.com/2017/12/04/interview-tomas-macconmara-on-1917-in-ireland-and-the-death-of-thomas-ashe/#.Wt4hrH8h3IU

[15] O’Carroll was a Volunteer rather than a Citizen Army member, he was arrested and summarily executed by Captain Bowen Colthurst at Portobello Barracks. For the tollof the Rising on the labour movement, see, Padraig Yeates, A City in Wartime, Dublin 1914-1918 p.125

[16] Conor Kostick, Revolution in Ireland, p.35

[17] C Desmond Greaves, The Irish Transport and General Workers’ Union, The Formative years, p. 187

[18] Townshend, Easter Rising p. 78

[19] Townshend, The Republic, p.11, In 1863 Lincoln imposed the draft on the Unioni States during the American Civil War, a policy that sparked off bitter rioting in New York and others places, especially, as it happens, among Irish immigrants.

[20] Townshend The Republic, p.11

[21] Ibid.

[22] Full text of Sheehan’s speech available here: http://en.wikisource.org/wiki/Irish_Anti-Conscription_Crisis.

[23] Henry Peel, The Scourge of Conscription, St Martin de Porres magazine, a publication of the Irish Dominicans.http://www.catholicireland.net/the-scourge-of-conscription/

[24] Maurice Walsh, The News from Ireland, Foreign Correspondents and the Irish Revolution, p.56

[25] Townshend, pp.341-342

[26] Ernest Blythe, BMH WS 939

[27] Laurence Nugent BMH WS 907

[28] The Ancient Guild of Incorporated Brick and Stonelayers Trade Union.

[29] John Hogan, From Guild to Union the Ancient Guild of Incorporated Brick and Stone layers Trade Union in pre-independence Ireland. P.81-82 http://doras.dcu.ie/19556/1/John_W_Hogan_20130930140824.pdf

[30] Greaves the Irish Transport and General Workers Union, p.200-202

[31] Nugent BMH

[32] Some notably Conor Kostick, in Revolution in Ireland p.39, blamed the ‘pan Catholic’ character of the anti-conscription campaign for the reluctance of Ptotestant Belfast workers to join it and William O’Brien in particular for launching ‘no real campaign’ against conscription in the northern city.

[33] Greaves the Irish Transport and General Workers Union, p.200-202

[34] Ibid. Though as Padraig Yeates has noted, many rank and file British trade unionists could not understand why they should be drafted and the Irish should ‘shirk’. See History Ireland, April 2018.

[35] Townshend the Republic, p.10, 15

[36] Dave Hennessy, The Hay Plan and Conscription in Ireland http://www.waterfordmuseum.ie/exhibit/web/Display/article/283/6/The_Hay_Plan__Conscription_In_Ireland_During_WW1_The_Hay_Plan.html

[37] Kostick, Revolution in Ireland, p.42

[38] Townshend, Easter 1916, p340