‘A fight to the finish’: The hunger strike of Michael Fitzgerald, 1920

By Gerard Shannon

On 10 April, 1923, Liam Lynch, IRA Chief-of-Staff, lay dying of bullet wounds in a public house in Castletown village, near Clonmel, Co. Tipperary. Lynch had been wounded following a dramatic shoot-out in the Knockmealdown mountains with a search party consisting of National Army soldiers during the Irish Civil War.

He had a request of Captain Laurence Clancy, the leader of the search party, who now tended to him: ‘I must be dying and I want to ask you to do a couple of little things for me… When I die tell my people I want to be buried with Fitzgerald of Fermoy.’

The name registered with Clancy, who recalled the name of Michael Fitzgerald, a Cork IRA leader who had died on hunger strike in late 1920. He asked Lynch if this was the same individual. ‘Yes,’ Lynch replied. ‘The greatest friend I ever had on this Earth.’[1]

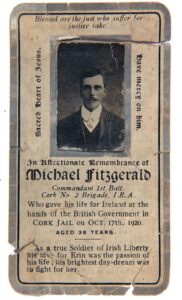

Michael Fitzgerald died on hunger strike in October 1920, the first IRA to so die during the War of Independence

Fitzgerald was the first republican hunger striker to die at the height of the Irish War of Independence. Forever overshadowed in public memory by the death of fellow hunger striker Terence MacSwiney, the Lord Mayor of Cork, who died shortly after him, Fitzgerald’s story is, nevertheless a compelling insight into the suffering and commitment of mid-level Volunteer leaders at the time.

Who was he and why did he leave such an impact on Lynch?

Early Life

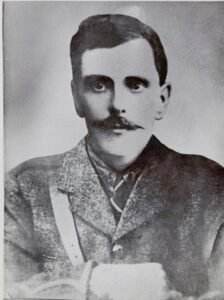

Fitzgerald was born on the 19 December 1881, in the rural townland of Ballyoran on the main Fermoy-Castlelyons road. Fitzgerald was the only son of his father, Edmond Fitzgerald, and wife, Margaret O’Brien, who died young. Some years later, Edmond remarried and there were six children in his second family, four sons and two daughters.

Growing up, Michael Fitzgerald was keenly aware of the activities of the local Land League, his father Edmund worked as a gardener for over sixty years on the local Briscoe estate. He also collected the tolls from the farmers who attended the monthly fairs. [2] While Edmund is not said to have taken part in the Land League, according to a sympathetic pamphlet by the historian Thomas O’Riordan, he ‘held patriotic principles. [3]

Michael Fitzgerald in the youth would hear accounts of the Fenian Rising in 1867 from locals, particularly the story of John McCarthy from Fermoy who escaped to the United States after the abortive Rising.[4] Fitzgerald was also remembered as ‘a great admirer and exponent of Gaelic games. He was also a keen participant in the Gaelic League in Fermoy.[5]

It was in May of 1900 that Fitzgerald went to work for a number of farming families in the Clondulane area for the next fifteen years. He became so well-liked and well-known as a resident in the area, he would be referred to locally as ‘Mick Fitzgerald of Clondulane’. As a young man, Fitzgerald was described about being about 5 foot 7 inches in height with dark hair and a ‘painted black moustache and lithe athletic appearance’[6].

Rise in the Ranks

Like many others in the locality, Fitzgerald joined the ranks of the local Irish Volunteers in Fermoy after the Easter Rising, having been radicalised by those events, particularly with the arrest of the Kents from Castleyons and the execution of local Volunteer leader, Thomas Kent.[7]

From the late 18th century, Fermoy could be classified as a ‘garrison town’, with a major British Army barracks based there. Uniformed soldiers were part of everyday street life of the town and central to the local economy.

Fermoy residents would regularly witness troops parading to Sunday religious services, marching to and from train stations and performing manoeuvres and reviews in public parks. Up to 3,300 troops were stationed in the barracks at one point in its history.

Fitzgerald came from near Fermoy, a garrison town, where he worked a farm labourer and then as a shop clerk.

By April 1917, the strength of the local Fermoy Volunteer company is said to have numbered around 60. At a meeting in the local Sinn Féin Club, the following officers were elected: Liam O’Denn as the Company O/C, Liam Lynch as the first lieutenant, Lar Condon as the second lieutenant, George Power as the adjutant and Mick Fitzgerald as the quartermaster. A brief reference is made to Fitzgerald meeting Liam Lynch in 1914, beginning what is described as a ‘lasting friendship.’[8] Lynch hailed from rural Limerick and had worked for a number of years as a shop assistant in both Fermoy and nearby Mitchelstown.

From this juncture, the Fermoy company, including Fitzgerald, held regular parades from the Thomas Kent Hall and foot drill carried on in the fields nearby.

In one dramatic incident in May 1917, the Fermoy Volunteers led a torchlight procession headed by Liam Lynch to celebrate the successful by-election in Longford of republican prisoner Joe McGuinness. On the way down Barrack Hill, both ‘separation women’ (that is, relatives of serving soldiers) and British soldiers attacked the Volunteers, during which Fitzgerald received facial injuries. Lynch ordered the company to ‘stand fast’ and ‘reform ranks’. Moving back to the town square, the parade was dismissed.[9]

In this same year, Fitzgerald changed his employment from St. Colman’s College to the flour mills at Clondulane. Until his arrest in 1919, he continued to reside with the Casey family in the village.

One member of the family recalled,

‘… Mick was a grand character. Everyone in Clondulane thought highly of him. I remember him as a great reader. He had copies of all the books written by Canon Sheehan, Charles Kickham and other Irish authors… Although he devoted most of his spare time to Volunteer work, Mick was always punctual in every detail.’

At this time, Fitzgerald also became the secretary of the Clondulane branch of the Irish Transport and General Workers Union.[10]

Fitzgerald frequently discussed with his close friend Liam Lynch how to improve the organisation of the Fermoy Battalion in the area. Like Lynch, Fitzgerald travelled the area by bicycle, visiting local companies, in efforts to increase the standard of the Volunteers’ training and discipline. It was said by his contemporaries that such was Fitzgerald’s sense of dedication he still turned up to work first thing in the morning, despite his lack of sleep from the late nights of drilling and instructing.[11]

Like other areas, the Fermoy Battalion within the Cork Brigade prepared for the possible imposition of conscription from Westminster and took part in the national resistance to it. With Lynch, Larry Condon and George Power, Fitzgerald devoted his time to preparing for armed resistance in and around Fermoy, in the event of conscription being enforced, at the instruction of the Brigade O/C, Tomás MacCurtain.[12]

In 1918-19 Fitzgerald was involved in a series of arms raids intended to capture weapons for his Volunteer unit

Both Lynch and Fitzgerald were keenly aware the battalion lacked arms. In May 1918, Fitzgerald, Lynch and Condon plotted a raid on a train arriving into Fermoy from Cobh. On this train was believed to be ammunition for the British army garrison of the barracks in Fermoy.

Despite careful planning, and involving up to fifty Volunteers, the leaders of the Battalion mistimed the arrival of the train and ultimately ended up empty-handed. Regardless of this setback, the planning of the operation and the preparedness involved, proved invaluable to the Battalion overall.[13]

By the beginning of the War of Independence, through arms raids, the Fermoy Battalion acquired 8 rifles, 30 shotguns, and a number of revolvers. Fitzgerald, along with others, busied themselves at the Fannings family home in Clondulane creating homemade bombs and grenades.

On 6 January 1919, at a meeting presided over by Tomás MacCurtain, at Walshe’s house at Clashabee near Mallow, the representatives of seven Battalions, including Fermoy, formed the Cork No.2 Brigade, or otherwise known as the North Cork Brigade. With Lynch elected as the Brigade O/C, within his former unit, Michael Fitzgerald became O/C of the Fermoy Battalion.[14]

Not long afterwards, Fitzgerald, on the suggestion of Con Leddy of the Araglen company began to plan a raid for arms and ammunition on the local RIC barracks in the town centre in Araglen. [15] When all the constables save one departed for morning Mass, seven Volunteers entered the rear of the building. They were suddenly surprised by the sole policeman who had been collecting water from nearby. Throwing the water in the Volunteers faces, the policeman attempted to run away and shouted he would ‘blow their brains out’ if he had a revolver.

Con Leddy recalled Fitzgerald’s amusement at this scene: ‘Michael Fitzgerald… was at this time looking down from an upper window of the barrack and very much enjoying the events taking place below. It was his happy day and perhaps his last happy day on this earth, although to suffer seemed to be a joy to him.’[16]

The policeman was held unharmed until the departure of the Volunteers following the raiding of the barracks. He thanked them before he left, and it has been suggested the policeman was so grateful for his treatment during the raid he refused to later identify any of the Volunteers. This raid added to the Battalion’s arsenal six rifles, a Webley revolver and a considerable amount of ammunition.[17]

Charged with possession of seditious literature Fitzgerald did three months in solitary confinement in Cork Gaol in 1919.

It was early in June 1919, that Fitzgerald was arrested at the flour mills where he worked in Clondulane. His arrest was the result of raids and searches by both British Army and RIC police in the area following the raid at Araglen barracks. A further raid on the house where Fitzgerald stayed found a quantity of ammunition.

On 15th June, Fitzgerald was tried by court martial at Victoria Barracks in Cork city in which he was charged with possession of a quantity of ammunition under the Defence of the Realm Act. Despite the ammunition found at his lodgings, he was acquitted of this charge, but was then immediately re-arrested and a further charge put to him: the possession of seditious literature. Fitzgerald was then sentenced to three months hard labour in Cork Gaol.

On his subsequent arrival to Cork Gaol, he found the republican prisoners were in the midst of a protest at their treatment, which descended into a riot and the smashing up of cells. As a result, Fitzgerald along with others, was placed in twenty-four solitary confinement on the No. 10 wing, only being released on Sunday to attend Mass.

Thomas O’Riordan suggests that the isolation and confinement took its toll on the active Fitzgerald. On 25th August 1919, with his sentence complete, Fitzgerald was released where he received a joyous reception among his friends in Clondulane.[18]

The Fermoy Arms Raid

On 7 September 1919, Liam Lynch led members of the Cork No. 2 Brigade in what became known as the Fermoy arms raid; an attempt by the Volunteers to seize arms belonging to members of the South Shropshire regiment as they made their way to a local church. It was the first military engagement the Irish Volunteers had had with British soldiers since the Easter Rising.

Fitzgerald insisted on taking part in the carefully planned operation, which came as a surprise to his comrades, given his recent imprisonment.[19] As Laurence Condon, a second lieutenant in the Fermoy Company recalled: ‘Fitzgerald was out only about ten days when the Wesleyan raid took place. He was in bad form for he had had a hard time in prison, having had about six months solitary confinement.’[20]

At 10.30am that morning, fourteen soldiers and a corporal marched from the British military barracks in Fermoy to make their way to the Wesleyan Church. The church was located at the eastern end of the town of Fermoy, about half a mile from the barracks. The soldiers carried their rifles ‘at the slope’ in other words over their shoulders, as on parade, rather than in combat readiness.

Fitzgerald was involved in the ambush of the South Shropshire Regiment as they paraded to Church in Fermoy in order to take their arms.

Around twenty-five Volunteers, armed with six revolvers between them, assembled in groups of two and three in the vicinity of the church, remaining spread out to avoid attracting attention. Lar Condon led the main attacking party, which included Michael Fitzgerald.

One car, containing Liam Lynch and other Volunteers, drove up behind the marching soldiers. In the vicinity of the church, Lynch emerged from the car and blew a whistle, demanding the soldiers surrender. The soldiers rushed the Volunteers, and a confused struggle took place. One soldier swinging a rifle butt at Lynch was shot dead, and three others wounded. The soldiers were disarmed and their rifles taken to nearby cars.

As part of the operation, Fitzgerald was in one of the cars that collected the seized arms. Driving to Kilmanger, the fourteen arms were left in a drain in the Kilbarry Woods. As the group dispersed, Fitzgerald walked across the fields with John Fanning. Both had to keep to the trees, as a low flying aeroplane was circling the area, apparently looking for the raiders.

The ambush in Fermoy had seen the death of nineteen year old Private William Jones, a member of the South Shropshire regiment. The only major upset among the Volunteers was that Liam Lynch himself had been slightly wounded in the ambush, but he quickly recovered. However, a reprisal by the British military – the first of its kind – followed in Fermoy that night, wrecking residences and local businesses.[21]

Returning to his residence on Clondulane, in the early hours of the morning Fitzgerald was awoken by a thunderous knocking on his door. Opening the door, he was greeted by police and military and informed by the officer-in-charge he was under arrest. Fitzgerald, and four others, were taken into custody and held in cells in the local RIC barracks.

Following the inquest by jury into Private Jones’ death, which found the shooting to have been unpremeditated, around 200 members of Jones’ regiment attacked business premises and residences in Fermoy that night. From their cells in the RIC barracks, Fitzgerald and his imprisoned comrades could hear a crowd gathering outside the barracks during the night shouting ‘They are here’ and ‘the murderers’.

From September, men arrested for their part in the ambush, including Fitzgerald, were remanded at weekly intervals and often paraded for identification purposes.

On 2 December 1919, at a special court held in Cork Jail Fitzgerald made the following statement to the judge: ‘I for one refuse to recognise this court. I do not want anybody to defend me or any relative of mine to do so.’ After Fitzgerald spoke, the other prisoners repeated the same statement.

Fitzgerald was later charged with the murder of the soldier who was shot dead in the Fermoy arms raid. He refused to recognise the court.

These weekly remands continued until 31April 1920 when Fitzgerald and seven others were charged with the murder of Private Jones the previous September. As he was being moved from the courthouse, Fitzgerald told Volunteer John Fanning, who was in the crowd, that ‘The Crown Solicitor has put a rope around our necks.’

During the summer of 1920, the trial was transferred to Derry. There on 21 July, the grand jury acquitted several of the men. However, Fitzgerald, along with two others, were deemed to have taken part in the killing of Jones and were remanded in custody.

Despite his ongoing detention, in the rural local elections in June 1920, Fitzgerald was elected to the Fermoy Board of Guardians, and was unanimously elected Vice-Chairman, but he of course attended no meetings due to his imprisonment. [22]

The Hunger Strike

On 8 August 1920, Fitzgerald and other republican prisoners delivered an ultimatum to the prisoner governor on 8 August. They had planned to begin a hunger strike at noon on 11 August, in protest at their continued detention without trial or conviction.

On 8 August 1920, Fitzgerald and other republican prisoners delivered an ultimatum to the prisoner governor on 8 August. They had planned to begin a hunger strike at noon on 11 August, in protest at their continued detention without trial or conviction.

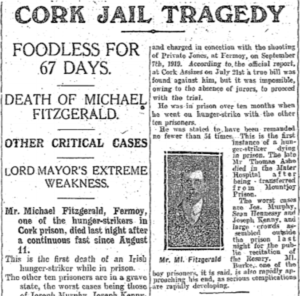

With no response, on the 11 August, the hunger strike began. By this point, Fitzgerald had been eleven months in custody. Medical officers began to monitor the hunger strikers, with many being released within a week.

Two days after the hunger strike began, Fitzgerald and Liam Lynch would meet in Cork Jail for what turned out to be the last time. Lynch had been arrested with other senior Cork officers, including Terence MacSwiney, at Cork City Hall. On meeting Fitzgerald, Lynch gave him a first-person account of all the Brigade activities in Fitzgerald’s absence. It was assumed that Lynch would now join the hunger strike, however, he was released on 15 August. Since he had given a false name to the British authorities, he had clearly never been properly identified.

Fitzgerald began a hunger strike at his continued detention without trial in August 1920. It would last just over two months.

Terence MacSwiney, the O/C of Cork No. 1 Brigade and Cork City Lord Mayor, did join the hunger strike. By the end of the second week, the British authorities had released or transferred to British prisons the majority of striking prisoners. This left eleven to continue the strike in Cork Gaol, including Fitzgerald, with Terence MacSwiney continuing his hunger strike on his transfer to Brixton Prison following his trial and sentencing on 16th August.

MacSwiney, given his high profile, was to keep the world media transfixed as own hunger strike progressed towards its fatal conclusion in the weeks ahead. Michael Fitzgerald, on hunger strike with the others in Cork Jail, as an individual drew less attention.

Thomas O’Riordan quotes from a friend of Fitzgerald’s who visited him one week into the strike in Cork Jail. Fitzgerald is said to have stated: ‘This strike is a fight to the finish. We shall continue to refuse food until our demands are met, otherwise we’ll never leave this place alive.’ [23]

Nonetheless, Fitzgerald remained in good spirits in the early days of the hunger strike and was a source of comfort to others during the initial pains and sufferings. Most days, Fitzgerald was visited by relatives in the Jail. By 22 September, he was emaciated and his body badly wasted. On 30 September, he took a turn for the worse due to the severe ulceration of his stomach. For several days, he could not keep down water.

A weakened Fitzgerald at this time said to a relative: ‘I have no complaint to make. They have offered me medical assistance which I refused. I am sorry to be such a cause of pain and anxiety to my relatives and friends. I am looking forward to death as a release from this suffering. I beg God for mercy and for strength to sustain me in this struggle.’[24]

One frequent visitor to Fitzgerald in the prison was Miss Ciss Condon, to whom he had been engaged to be married prior to arrest. Friends of Fitzgerald attempted to arrange for the couple to be married in the prison and Fitzgerald even securing a wedding ring which he kept under his pillow. Bishop Coughlan of Cork had granted permission for the ceremony.

However, the authorities got wind of this attempt, and threatened that if the wedding were to take place, all further visits to the striking prisoners would be halted. Not wanting to deprive the other prisoners of this privilege, Fitzgerald and Condon agreed to not to proceed with the marriage.[25]

By 10 October, Fitzgerald was unable to take a drink of water, and his sight and hearing began to fade. Over the next few days he was in a semi-conscious state and on the 15 lapsed into unconsciousness. It was at 9.45pm on 17 October, the 67th day of his hunger strike, Michael Fitzgerald died surrounded by priests and nuns reciting the rosary.

O’Riordan depicts a vivid scene: ‘Fr. Fitzgerald [the prison chaplin] led the recitation of the fifteen decades of the Rosary. Relatives of the other prisoners knelt outside in the corridor joined in the responses. At the same time voices of the huge crowd outside the gates could be heard as they also recited the Rosary. As Fr. Fitzgerald recited the second decade of the third rosary, one of the nuns turned around and said, ‘He’s gone.’ Fitzgerald was 38 years old.[26]

Aftermath

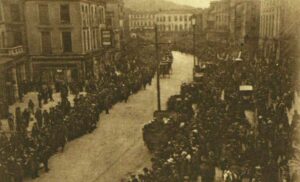

Cork City Hall was unavailable for the laying out of Fitzgerald’s remains, being prepared for the pending death of MacSwiney; instead, Fitzgerald was taken to St. Peter and Paul’s church. On the evening of 18 October, Fitzgerald was taken from the gaol to the church, where his body was dressed in a Volunteer uniform.

Cork City Hall was unavailable for the laying out of Fitzgerald’s remains, being prepared for the pending death of MacSwiney; instead, Fitzgerald was taken to St. Peter and Paul’s church. On the evening of 18 October, Fitzgerald was taken from the gaol to the church, where his body was dressed in a Volunteer uniform.

Six battalion commanders of Cork No.1 Brigade stood as an honour guard during the mass on the morning of the 19th, but the funeral mass was interrupted by a British military party. To the shock of the mourners, the officer served notice on the priest, Reverend Canon O’Leary, to inform him that only one hundred mourners could follow the coffin and not walk in military procession.[27]

On the same day, a military inquest was held into Fitzgerald’s death at Victoria Barracks in Cork, over by three British military officers.

He died on October 17, 1920, on the 67th day of his hunger strike.

The governor testified that Fitzgerald had declined all medical treatment from doctors up to the day before his death. The governor did not believe that Fitzgerald’s attitude to the hunger strike had been shaped by visitors to the prison. In addition, the prison doctor gave evidence that he had recommended Fitzgerald’s release on medical grounds in early September 1920 but had not received an answer from the prison authorities.

The inquest ultimately concluded – in typical language for the British authorities – Fitzgerald was of ‘sound mind and deliberately caused his own existence to end and did feloniously kill himself’.[28]

From Cork City, Fitzgerald’s coffin was taken from Cork City for a funeral mass at St. Patrick’s Church in Fermoy. Arrangements were made for Liam Lynch, then on the run, to pay his respects on the night prior to the funeral.

With the lid of the coffin unscrewed, Lynch looked down on his friend’s remains in anguish and sorrow, clasped his hand and departed the church. Fitzgerald’s biographer wrote with a typical, hagiographic flourish: ‘Lynch passed out of the Church, with set face and down the streets he so often walked with Mick Fitzgerald. … Never afterwards did Liam Lynch forget his old comrade.’[29]

Indeed, before the Truce, Lynch wrote to his mother: ‘I am living only to bring the dreams of my dead comrades to reality, and every moment of my life is now devoted to that end… thank God I am left alive to still help in shattering the damned British Empire.’[30]

Matt Flood of the Fermoy company recalled immense tension in the air on the day of the funeral in the town, with most businesses closed, while the British military were determined to not allow a large parade to the cemetery.[31] Despite this, members of the Fitzgerald’s Battalion were keen to give their fallen leader a proper send-off.

As Patrick Ahern of the Fermoy Company recalled:

‘As the remains were being removed from the church, word was received that a force of British military were guarding the bridge over the Blackwater on the funeral route to Kilcrumper. The Volunteers detailed as “Firing Party” then dumped arms for the time being and the funeral proceeded towards the bridge where there was a general hold-up and only a small number of people were allowed to pass the cordon.

However, large numbers reached Kilcrumper via the Viaduct as I had done on the day of the Wesleyian raid and there was quite a good gathering at the burial in Kilcrumper where the graveyard was also surrounded by a strong force of military.

After the burial the crowd dispersed and the military returned to barracks. Immediately following the withdrawal a firing party composed of John Fanning, Daithi Barry and myself, who were armed with revolvers proceeded to Kilcrumper and fired three volleys over the grave of their late Battalion O/C. They then dumped their guns and returned home.’[32]

The hunger strike in Cork Jail ended on 12 November 1920, with nine survivors. MacSwiney died in Brixton on 25 October after 74 days on hunger strike, with Volunteer Joseph Murphy dying the same day after 76 days. Murphy was twenty-five years old, and like Fitzgerald, was greatly eclipsed in historical memory by MacSwiney.

Legacy

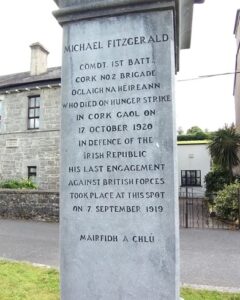

In 1922, Fermoy Urban Place voted to rename Old Market Place in Fermoy town to Fitzgerald Place. Also, in 1945, the GAA grounds were named Michael Fitzgerald Park, on the site on the former army barracks. On the fiftieth anniversary of Fitzgerald’s death in 1970, a memorial to him was unveiled by his family and surviving comrades in O’Rahilly Row in Fermoy, still standing today at the site of the Fermoy arms raid in September 1919.

In 1922, Fermoy Urban Place voted to rename Old Market Place in Fermoy town to Fitzgerald Place. Also, in 1945, the GAA grounds were named Michael Fitzgerald Park, on the site on the former army barracks. On the fiftieth anniversary of Fitzgerald’s death in 1970, a memorial to him was unveiled by his family and surviving comrades in O’Rahilly Row in Fermoy, still standing today at the site of the Fermoy arms raid in September 1919.

The monument has shamrock motifs and a ringed cross, typical of nationalist monuments in Ireland and harking back to the Celtic Revival period. It can be found on the green in front of the courthouse in Fermoy town and closing the vista east from the main street.

As noted by William Murphy in his study, Political Imprisonment & the Irish, 1912-1921, the death of Terence MacSwiney on 25 October greatly overshadowed the deaths of Fitzgerald and Murphy in Cork Gaol and resulted in the group in Cork Jail ‘rendered almost faceless by [their] collective action.’

Murphy has further argued that in ‘their martyrdom [the dead hunger strikers] come to exist outside time, joining an ahistorical elite or tradition within Irish nationalism. Consequently, their deaths, and very often their lives, tend to be stripped of all other meaning, unmoored from their complexity of context.’[33]

Liam Lynch, anti-Treaty IRA Chief of Staff in the Civil War, on his deathbed, asked to be buried beside his old friend and comrade Michael Fitzgerald.

In the months following to the Truce, through the signing of the Treaty, and in the lead-up to the Civil War, Liam Lynch made frequent reference to living up to what his comrades such as Fitzgerald died for.

For instance, In September 1921, he remarked to his brother Tom: ‘Certainly were it not that I continually think of my dead comrades and the glorious cause we fight for it would be more than impossible sometimes to carry on… In justice to the yet unborn as well as to the dead past we have no other authority but to fight on…’[34] By March 1922, Lynch was elected Chief-of-Staff of the anti-Treaty IRA.

Lynch himself, on his death, was buried with Fitzgerald in Kilcrumper as per his request. Republican leaders requested to have Lynch buried with the usual pomp and ceremony in Dublin’s Glasnevin cemetery, but Lynch’s family were determined to uphold his wishes.[35],

The effect of Lynch’s request to be buried with Fitzgerald still left its impact on former IRA and National Army officer Laurence Clancy three decades later.

When he wrote to Liam Lynch’s biographer, Florrie O’Donoghue in February 1953, Clancy recalled: ‘I read and knew about Lynch and his exploits against the Tans before that fateful day when we met on the Knockmealdown mountains; hence, the affection I felt for a great soldier of Ireland, even as my opponent in arms in a regrettable Civil War. Thus, when he spoke of Fitzgerald he was only bringing back to my mind vivid memories of the past. Great men in a glorious cause gone before us, their comrades, who were now in arms against each other.’[36]

Gerard Shannon has an MA in History from the DCU School of History and Geography. He is currently writing a new biography of Liam Lynch to be published by Merrion Press.

References

[1] Untitled account of Liam Lynch’s capture and death by Lawrence Clancy, n.d., Florence O’Donoghue Papers, NLI Ms 31,423(4).

[2] Thomas O’Riordan, The Price of Freedom: The Life Story off Mick Fitzgerald (Commandant) O/C 1st Battalion Cork No. 2 Brigade, (Fermoy, n.d.), pages 1-2.

[3] Ibid, page 3.

[4] Ibid, page 5.

[5] Ibid, page 8.

[6] Ibid, pages 12-13.

[7] Ibid, pages 23-24.

[8] Ibid, page 28.

[9] Bureau of Military History, Patrick Ahern, Witness Statement No. 1003, page 2.

[10] O’Riordan, The Price of Freedom, page 25.

[11] Ibid, page 29.

[12] Florence O’Donoghue, No Other Law: The Story of Liam Lynch and the Irish Republican Army, 1916-1923, (Dublin, 1954), page 23.

[13] Ibid.

[14] O’Riordan, The Price of Freedom, page 38.

[15] BMH, Con Leddy, WS No. 756, page 5.

[16] O’Donoghue, No Other Law, pages 45-46.

[17] Ibid, page 46.

[18] O’Riordan, The Price of Freedom, pages 43-45.

[19] O’Riordan notes Fitzgerald going against ‘the advice of friends’, Ibid, page 46.

[20] BMH, Laurence Condon, WS No. 859, page 5.

[21] See O’Donoghue, No Other Law, pages 50-55, among other accounts.

[22] O’Riordan, The Price of Freedom, pages 49-57.

[23] Ibid, pages 69-70.

[24] Ibid, pages 75-76.

[25] Ibid, page 78.

[26] Ibid, pages 79-80.

[27] Ibid, pages 80-82.

[28] See ‘Hunger striker Michael Fitzgerald dies in Cork Gaol’: https://www.rte.ie/centuryireland/index.php/articles/hunger-striker-michael-fitzgerald-dies-after-67-days-without-food (accessed online 16th October 2020).

[29] Ibid, page 83.

[30] Liam Lynch to Mary Lynch, 22 July, 1921, Liam Lynch Papers, NLI Ms 36,251/17.

[31] Bill Hammond, Soldier of the Rearguard: The story of Matt Flood and the Active Service Column, (Fermoy, 1977), pages 32-33.

[32] BMH, Patrick Ahern, WS No. 1003, page 21.

[33] William Murphy, Political Imprisonment and the Irish, 1912-21, (Oxford, 2014), pages 174-75.

[34] Liam Lynch to Tom Lynch, 26 September 1921, Liam Lynch Papers, NLI Ms 36,251/20.

[35] Hammond, Soldier of the Rearguard, page 65.

[36] Laurence Clancy to Florence O’Donoghue, 4 February 1953, Florence O’Donoghue Papers, NLI Ms 31,434(4).