Today in Irish History -The Shooting of Tomás MacCurtain, March 20, 1920

The assassination of the Lord Mayor of Cork, March 20, 1920. By John Dorney

Early in the morning of March 20, 1920, armed men in disguises or with faces blackened with soot, banged on the front door of the MacCurtain family home in Blackpool, Cork city.

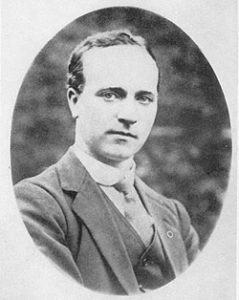

The head of the household was Tomás MacCurtain, the Sinn Féin Lord Mayor of Cork and also commandant of the Cork No. 1 Brigade of the IRA.

The intruders pushed past MacCurtain’s wife Elizabeth and upstairs to their bedroom, ignoring the couples’ five children, some of whom had begun to scream. At the door, one of the men called ‘come out Curtin’. When MacCurtain appeared at the bedroom door, they shot him three times in the chest. He died a few minutes later. It was his birthday, he was 36 that day.

MacCurtain the lord mayor of Cork was shot dead in front of his family by men thought to be plain clothed RIC constables.

The killers rushed downstairs and into the night, amid cries of ‘murder’ from MacCurtain’s family. They were followed for a few steps by MacCurtain’s brother in law James Walsh, until they turned to fire shots at him and he flung himself to the ground. Despite being within sight of King Street Royal Irish Constabulary (RIC) barracks, no arrests were ever made. Indeed according to one account the killers returned to that Barracks when the job was done.

It later emerged that other armed men had put out the gas lights in the vicinity of the MacCurtain house, while others stopped traffic in nearby streets. [1]

It was widely believed that the shooting was the work of RIC constables, in revenge for the fatal shooting the day before of Constable James Murtagh in Cork city. Indeed the inquest jury returned a verdict of ‘wilful murder’ against the RIC, ‘directed by the British government’ and Prime Minister David Lloyd George.

It was one of the first killings in Cork during the Irish War of Independence, but far from the last. MacCurtain is listed at a registry of fatalities from political violence in County Cork number 22 out of 528 dead from 1919 until July 1921.

Tomás MacCurtain

Tomás MacCurtain became one of the most famous republican martyrs of that era.

Over 15,000 people attended his funeral. Later a street was named after him in Cork and annual commemorations are still held on the anniversary of his death.

However MacCurtain had a more complicated relationship with the emerging IRA guerrilla campaign than one might suppose.

He, like a great many of his peers in the republican movement, came to separatist nationalism via cultural nationalism, in particular the Irish language movement, the Gaelic League. It was there that he met his wife Elizabeth and it was his enthusiasm for the language that led him to change his name from Thomas Curtin to the Irish form, Tomás MacCurtain.

MacCurtain, a leading light in separatist circles in Cork, mobilised his men for the Rising of 1916 but was talked into a humiliating surrender.

In between his political and cultural activities he ran a successful business, a factory that produced women’s clothes.

However, at a relatively early stage, he graduated into political militancy, joining the youth group the Fianna, the Irish Republican Brotherhood and then the military group, the Irish Volunteers. By 1915 he had become the Cork Brigade Commandant of the latter.

At Easter 1916 when the insurrection broke out in Dublin, he received a string of contradictory orders from the capital, as a result of Eoin MacNeill’s countermanding order. First he was to mobilise his men, then to stand them down again and then to mobilise them again. The result, predictably was utter confusion. He and several hundred of his men spent Easter week holed up in their drill hall on Sheares Street in Cork, with the British military threatening to shell the city and the Catholic Bishop Daniel Coholan pleading with him to surrender.

MacCurtain it seems was in favour of surrender, but decided to put the decision to a vote of his Volunteers, who refused. Later in the week it was agreed that their arms would not be handed over to the British but put in the safe keeping of the mayor, Thomas Butterfield and returned at a later date.

This might have sounded plausible to MacCurtain at the time, the Volunteers being, before the Rising, a legal organisation and holding arms openly, but predictably enough the British confiscated the weapons and interned MacCurtain, his deputy Terence MacSwiney and several other prominent Cork Volunteers at Frongoch. [2]

After the general release of prisoners in 1917, MacCurtain and MacSwiney were summoned to Dublin to explain themselves to the Volunteer leadership. They must have done a good job, as they remained at the head of republican organisation in Cork in the years that followed. Nevertheless, both would go to great lengths to wipe out the ‘shame’ of their surrender without firing a shot in 1916.[3]

War of Independence

By 1918, after the national mobilisation against conscription, the Cork Brigade was up to 8,000 men and early in the following year it was decided to split it up into three Brigades, the First in Cork city and North Cork, Number Two in East Cork and Number Three in West Cork. MacCurtain became commandant of the First Brigade.

In January 1920, MacCurtain was also elected as a Sinn Féin candidate, to Cork corporation and elected Lord Mayor of the city by the other councillors.

MacCurtain was commandant of Cork No 1 Brigade of the IRA but favoured a ‘second rising’ rather than individual assassination of policemen.

MacCurtain at this point appears to have been in favour of a ‘second rising’ in which all the men under his command would make massed assaults on police barracks. He was, perhaps fortunately, dissuaded by the more realistic Volunteer Chief of Staff Richard Mulcahy, who favoured small scale guerrilla action. [4] MacCurtain was instead brought to Dublin by Michael Collins and participated in one of the failed attempts to kill the Lord Lieutenant Sir John French. [5]

MacCurtain was, however against individual shootings on the whole, as opposed to a mass insurrection. He resisted a suggestion of IRA GHQ that a ‘special squad’ should be set up in Cork, as it had been in Dublin, for this purpose. [6]

Many of his men, however were impatient for action. In part to satisfy them, IRA GHQ sanctioned attacks on police barracks in January 1920, three of which were attacked in a single day in Cork.

However this was not enough for some of the men notionally under his command, notably Sean O’Hegarty. The latter without orders raided the arsenal at a grammar school in Cork (at that time, some prestigious schools instructed their male pupils in arms and drill) and seized 50 rifles. He was also involved in the non fatal shooting of a policeman. For this MacCurtain attempted to have him court martialled, but while the charges of insubordination failed to stick, O’Hegarty left the IRA in disgust.[7]

However by now a vicious cycle of violence was developing between the IRA and the RIC in Cork. As March 1920 dawned, a District Inspector, McDonagh was shot and wounded in the city, after which the police broke the windows of the Sinn Fein club and badly beat several Sinn Féin aldermen.[8]

And on March 19 1920, Constable James Murtagh was shot and killed by IRA members on Pope’s Quay in the centre of Cork. Tomás MacCurtain disapproved of the killing, it being contrary to his ideas of how revolutionary war should be fought.

For one thing it was not sanctioned by his Brigade command. He remarked, ‘we can’t have men roaming around armed shooting police on their own’.[9]

But he also seems to have regretted it on a personal basis, by one account calling to give condolences to Murtagh’s family on the evening before his own death. [10]

This did not stop the RIC from holding him responsible and though the culprits for his killing were never identified, his killers were almost certainly RIC constables operating in plain clothes, but with a significant degree of organisation, indicating some direction from higher ranks.

However, the effect of the assassination of MacCurtain was that the Cork city IRA became more combative, not less. McCurtain was succeeded as commandant of Cork No 1 Brigade by Sean O’Hegarty, whom MacCurtain had sidelined for his militant methods. O’Hegarty proved a capable and ruthless commander in the months ahead. MacCurtain was succeeded as mayor by his friend Terence MacSwiney who would die on hunger strike in November of that year.

One man the IRA held responsible for MacCurtain’s killing was RIC District Inspector Oswald Swanzy, who had ‘dogged’ MacCurtain throughout the preceding months.

MacCurtain’s killing was avenged by the shooting of RIC DI Swanzy in Lisburn, Co Antrim, which led to an outbreak of deadly rioting in the north.

Perhaps significantly, directly after the shooting, Swanzy was transferred out of Cork, back to his native Antrim. He was tracked there by the IRA in August 1920 and gunned down as he left Church in Lisburn. One of the gunmen, from Cork, allegedly used MacCurtain’s own revolver in the killing.[11] That night loyalists wrecked the Catholic quarter of that town, in revenge killing one person and burning 60 houses.[12] Rioting soon spread to Belfast where it claimed more lives.

Tomás MacCurtain’s death was regarded, not unreasonably, as a signal case of the ‘British tyranny’ holding Ireland in subjection. But examined in context, it is also a grim insight into the cycles of killing and revenge that punctuated the Irish War of Independence.

References

[1] For accounts of the killing see Peter Hart the IRA and its Enemies p.78-79, Also Michael Murphy BMH WS 1579

[2] For an account of Cork during Easter Week 1916 see, BMH Michael Walsh WS 1521 and BMH Michael Murphy WS 1547

[3] Michael Hopkinson, The Irish War of Independence, p.104

[4] Hopkinson, War of Independence, P. 105

[5] Charles Townshend, The Republic, The Struggle for Irish Independence, p.107

[6] Townshend The Republic p.109

[7] Townsend, The Republic p.110, Hopkinson War of Independence, p.109

[8] Hart, IRA and its Enemies, p77-78

[9] Townshend The Republic, p.110

[10] Hart, IRA and its Enemies p.78

[11] Michael Murphy BMH

[12] Hart P.79