The Wiggan’s Patch Massacre, Pennsylvania, 1875

The terrible murders of Charles O’Donnell and Ellen McAllister. By John Joe McGinley

Early in the morning of December 10th, 1875, a large group of masked and armed men broke into the boarding house of elderly Irish immigrant Margert O’Donnell in Wiggan’s Patch, Schuylkill County, Pennsylvania in the north-eastern United States of America.

Margaret O’Donnell had left Gweedore in County Donegal with her husband Manus to escape grinding poverty. Manus died in Dec 1867 aged 45. Now a widow Margaret ran a boarding house at 140 Main Street in Wiggan’s Patch, now called Boston Run, Schuylkill County, Pennsylvania.

Margaret lived with her sons James and Charles, her 20-year-old daughter Ellen and her Husband Charles McAllister. Ellen was the mother of an infant son and was heavily pregnant.

Two Irish immigrants, Charles O’Donnell and pregnant Ellen McAllister, were shot dead at Wiggan’s Patch boarding house on the night of December 15, 1875

The armed intruders were seeking vengeance against two alleged members of the ‘Molly McGuires’, a secret society based among Irish coal-miners in the region, Margaret’s sons, Charles and James. (1)

In the space of 20 minutes, Margaret would find herself pistol whipped, her son Charles riddled with bullets then set on fire and her heavily pregnant daughter Ellen Mc Allister murdered, shot in the stomach as she came to the aid of her mother and brother.

What could have caused such a savage attack on an unarmed family? The causes were to be found in the bitter and violent labour disputes between the Irish immigrant miners and the mine owners in that region.

A time of turmoil and toil

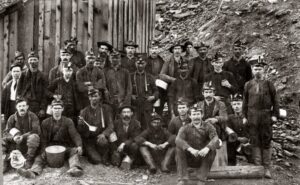

It was a turbulent time in north-eastern Pennsylvania, with labour unrest in the anthracite coal mining region, where Irish immigrants toiled in dark and unsafe conditions.

Working life for the Irish emigrants in the mines of Pennsylvania in the 1870s was dangerous and exploitative. Many had escaped the famine that stalked their native land in the 1840s hoping for a better life in America.

Sadly, for some they had exchanged hunger for the dangerous and poorly paid profession of coal mining. Young and old laboured in the dark mines of Schuylkill county. Of the 22,500 miners almost a quarter where children and some as young as five were employed by the coal companies. (2)

Conditions for the largely Irish coal miners in 1870s Pennsylvania were harsh and labour relations violent.

While many of the miners and foremen were Welsh immigrants the vast majority of those who toiled, underground were unskilled labourers from the growing Irish population. By 1870 the Luzerne and Schuylkill counties had 38,075 Irish born residents and a large number of second generation Irish- Americans. (3)

Not only where working conditions unhealthy and unsafe, when the miners received their pay it was soon taken from them in the ‘company store.’ Mine workers were forced to buy their weekly provisions from a store owned by the mine owners at a large mark up. It was not uncommon for workers to actually end up owing the company more money that they had been paid. This indebtedness tied them to the mine, almost in the condition of indentured labour. (4)

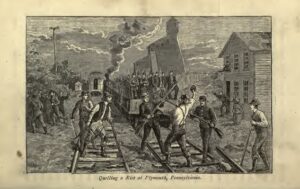

The Irish tried peaceful methods to improve conditions with the formation of a union named the “Workingmen’s Benevolent Association.” Despite some small improvements, the ‘Great Panic’ of 1873 (one of the worst depressions in American history) gave mine owners the perfect opportunity to further erode wages and conditions of the miners.

The mine bosses imposed a new contract framework on the Irish mine workers and their colleagues which resulted in pay rates being reduced by as much as 20%.

The workers did not take this lying down, however and in 1875 began a strike that lasted seven months. This was to ultimately end in failure after the Pennsylvania governor called in the troops to break the strike. Defeated and demoralised, the mine workers were forced back underground to work, accepting the new rates of pay. The union was irreparably damaged and faith in peaceful protest was lost.

The Molly Maguires society emerged from this background. They had originated in Ireland in the 1840s as a response to miserable working conditions and landlord evictions and were the latest in a long line of rural secret societies including the Whiteboys and Ribbonmen.

The Molly Maguires society emerged from this background. They had originated in Ireland in the 1840s as a response to miserable working conditions and landlord evictions and were the latest in a long line of rural secret societies including the Whiteboys and Ribbonmen.

Many of the Irish immigrants who relocated to the Anthracite coal region of Pennsylvania originated from oppressed rural regions of Ireland where the Molly Maguires and other secret societies had fought for tenant farmers’ rights. In America, after peaceful methods had failed, in desperation they turned to violence to achieve fair working conditions and to fight back against the heavy-handed tactics of the mine owners.

The Molly Maguires, a rural secret society transplanted from Ireland to America, used traditional agrarian methods of intimidation and sometimes violence, to further miners’ cause.

Now operating in America, The Mollies were a secret society based among the Irish coal miners in the anthracite fields of northern Pennsylvania in the 1860s and 1870s. Thousands of miles away from their native Ireland in the anthracite coal mines of Pennsylvania, rather than exploitative landlords, the new targets for the Molly Maguire’s were mine owners, company policemen and strike breakers.

Many of the Molly Maguires were also members of the Ancient Order of Hibernians (AOH), although not all members of the latter approved of the tactics of the ‘Mollies’, as they soon became known.

Intimidation, assaults and sometimes murder were employed by the Molly Maguires to rectify the grievances they felt could not be dealt with by a legal and political system that was hostile to immigrants and the working class. The 1870’s were a period of great unrest in the Pennsylvanian coal mines. (5)

The Murder of Sanger and Uren

The O’Donnell’s were caught up in this turmoil as Charles and James were suspected of being members of the Molly McGuires. Along with Ellen’s brother-in-law James McAllister they were the chief suspects in the murder of mine boss Thomas Sanger and miner William Uren on September 1st, 1875.

This killing was widely thought to have been carried out by the Molly Maguire’s in revenge for Sanger’s perceived ill treatment of mine workers.

Sanger had been foreman at Heaton’s Colliery in Raven Run near Girardville for three years and had a history of sacking Irish workers he suspected of being Molly McGuires.

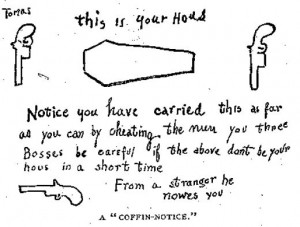

He received a threatening ‘coffin notice’ (a threatening letter with a picture of a coffin drawn on it) from the Molly Maguires in 1874 but had figured by this time the anger of his enemies was forgotten or appeased.

Two men, mine foremen Thomas Sanger and William Uren were assassinated by suspected Molly Maguires in September 1875.

But this was not the case. He was gunned down as he walked along a busy street to work. Uren a miner and friend of Sanger, who boarded with his family, was also slain by the gunmen to eliminate him as a witness.

Robert Heaton, the proprietor of the colliery, bravely pursued the fleeing murderers and exchanged fire with them using his own revolver. No one was hit as the murderers fled up a mountain path and into thick woods to safety. Heaton organised a pursuing party and offered a $1,000 reward. (6)

‘Blackjack’ Kehoe

While there was no concrete evidence linking the O’Donnell’s and McAllister to the murders, there was an obvious connection linking them to the Molly Maguires. Margaret O’Donnell’s other daughter Mary Ann was married to Jack Kehoe an innkeeper who was widely known as the ‘king’ of the Molly Maguire’s.

Jack Kehoe, known best by his nickname “Blackjack”, was a charismatic Irish immigrant from County Wicklow. He had worked as a miner for several years after arrival in America before going into the tavern trade. An intelligent and gregarious man, he decided to move to the growing coal town of Girardville, were he opened a tavern and established himself as a well-liked and respected businessman.

Jack Kehoe, an Irish miner turned inn-keepr, was suspected of being the head of the Molly Maguires.

Once settled in Girardville, Kehoe became its High Constable, which was an elected position with responsibility for keeping the peace, appointing other constables and ensuring the security of elections in their area.

Despite his position he did not forget those he had laboured alongside in the dark bowels underground. An active member of the Ancient Order of Hibernians, and a staunch supporter of the rights of coal miners, Kehoe earned the respect of the coal miners and resentment of the owners. He was an eloquent spokesperson for the union movement.

Kehoe’s efforts to improve the lot of the Mine workers led to suspicions that he was the mastermind of the Molly Maguire activity in the area, and he earned the enmity of Franklin Gowen, the President of the Philadelphia and Reading Coal and Iron Company. Gowen disliked Kehoe’s rallying of the miners toward unionisation. He tried to repress the miners’ efforts in every way possible including slander and subterfuge. (7)

The Pinkerton Detective agency

Franklin Gowen brought the mine owners together in the Anthracite Board of Trade and his response to the Mollies was to hire the Pinkerton Detective Agency to root out the Molly Maguires from the coal fields.

Pinkerton operative and Armagh native, James McParland was selected to infiltrate the Mollies and report back to the Pinkerton agency on their actions. Within a short time, McParland had successfully ingratiated himself with the Mollies. He observed and participated in several Molly Maguire operations. and even became secretary of the local AOH lodge.

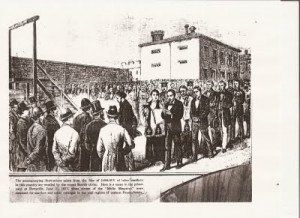

McParland would eventually provide the evidence that would lead to the hanging of Jack Kehoe and 19 other Irishmen, executed in 1877 for membership and the alleged crimes of the Molly McGuires. (8)

The thirst for Revenge Grows

However, back in late 1875, people now demanded justice for the murders of Sanger and Uren, McParland’s reports would first impact on the O’Donnell’s at Wiggins Patch who would pay a heavy price for their alleged membership of the Molly Maguires.

The mine owners using the Pinkerton Agency wanted to put a swift end to the Molly McGuire’s attacks on their employees. The majority non-Irish population shocked by the murder of Sanger and Uren in their community also wanted the culprits brought to justice.

The Pinkertons published names of suspected Molly Maguires and, with miner owner’s armed militia at large, it amounted to incitement to murder.

Anglo-Americans were either indifferent to the conditions under which the Irish lived or they were actively hostile towards the Irish presence in America. The Irish were stigmatised for being Roman Catholics and stereotyped as drunks and criminals. At the same time, they were also feared because many thought they would take political control of the region as they had In New York and Boston. (9)

The press also wanted vengeance and local newspapers were explicit in calling for vigilante committees. The Shenandoah Herald plainly stated that the institutions of the law were powerless against the Molly Maguires and that it was time to “take the law in our own hands and drive the men who are known to be at the bottom of the murders out of the district.” (10)

The Pinkertons, using the information gathered from their agent, McParland, released a document listing the names, addresses, and AOH ranks of 31 suspects in various murders committed in 1875 by the Molly Maguires.

It stood as an open invitation for vigilantes to take the law into their own hands. The list included James O’Donnell, Charles O’Donnell, Thomas Munley, Charles McAllister, James McAllister and Mike Doyle as the suspected murderers of Sanger and Uren.

The list said the O’Donnell brothers and both Charles and James McAllister lived at Margaret O’Donnell’s boarding house in Wiggans Patch, “a small mine patch near Mahanoy City.” (11)

All the vigilantes had to do now was to decide when to strike.

One early historian of the Molly Maguires observed that, although the McAllister’s and the O’Donnell’s were suspected of the crime, “it was beginning to be believed that the guilty parties would entirely escape punishment.” (12)

Vigilantes were largely recruited from the ranks of the Silliman Guards, a local militia in Mahanoy City. The Silliman Guards had previously been used before by the mine owners to enforce their will and break strikes in the minefields. They also acted without fear of arrest from the mine owner-controlled local police force.

The tragedy unfolds

In a tragicomic beginning to a terrible tragedy, the vigilantes became lost. Perhaps this was because it was a dark night or the Pinkertons had given incorrect directions. After knocking on a number of doors, the motley crew of would-be assassins finally received directions to the O’Donnell boarding house. (13)

Margaret O’Donnell was badly beaten, James McAllister was hung from a tree but miraculously survived.

It was a cold December night; Margaret O’Donnell was the last to go to bed. Before she went upstairs, she laid down a fire to keep the house warm and ensure her heavily pregnant daughter Ellen McAllister, who was due to give birth the next day was warm and comfortable.

At about 1am in the morning Ellen McAllister was awakened by a loud noise. It was as if a hoard of people were marching over the lawn. Ellen asked her Husband Charles to investigate.

Suddenly the door of the boarding house was kicked in and around 30 well-armed and masked men flooded into the house banging on doors and firing their guns. According to the later testimonies of witnesses, some wore oilcloth coats and carried lanterns to show them the way through the dark colliery town. Most wore masks to conceal their identities. (14)

The intruders began searching for their targets. Charles O’Donnell was first to be dragged from his bed. A group of the insurgents surrounded him and riddled his body with as many as 18 bullets. His body was taken outside and set on fire. (15)

Charles O’Donnell was ‘riddled’ with bullets and his body burned. Pregnant Ellen McAllister was shot through the stomach and killed along with her unborn child.

The masked men knew who they had come for and soon James McAllister the brother of Charles another alleged Molly McGuire, was dragged outside, and a noose was wound around his neck. He was hung from a tree in the garden and left for dead.

Miraculously he survived. He played dead and then wriggled free and ran for help to assist the O’Donnells. The intruders could not find James O’Donnell who was not present that night.

Ellen, her infant son and husband Charles now barricaded themselves in their room, fearing for their lives. Thinking everyone else was dead, Charles McAllister fled out of a back window and bolted into the darkness, chased by some of the gunmen leaving his heavily pregnant wife and young son.

Some would say this was cowardice, but Charles later claimed he was going for help for his family as he was sure as vicious as the masked men where they would not harm a child and pregnant woman.

This was sadly a naïve assumption as the masked men had already pistol-whipped Margaret O’Donnell into unconsciousness and were showing no mercy to anyone they felt was connected to the O’Donnell’s or the Molly Maguire’s.

Ellen though frightened and protecting her young son, could not bear the screams of her mother Margaret and left her room to plead with the assailants to stop. As she stood at the stop of the stairs, several of the intruders turned and looked at her.

One man raised his pistol and fired. The bullet hit Ellen in the stomach. Her eyes rolled in shock as she realised what had happened. Soon other intruders began firing at her. According to a later witness, Ellen’s right hand covered the blood pouring from her wound while her left hand was raised to deflect the hail of bullets. Another bullet pierced her left breast.

“My baby, Oh dear God, my baby!” Ellen cried out, blood trickling from the corner of her mouth. She gasped, faltered, and clung to the stairs for a few seconds. But her strength quickly faded, and she crumpled to the ground. (16)

One assailant was heard to admonish his compatriots:

“We don’t shoot women,” but it was too late for Ellen. (17)

This shocked the gunmen into silence and seeing what they had done they ran out of the door. Margaret O’Donnell lay unconscious but would soon recover.

In the following hours, Charles McAllister, and his wounded brother James made their way back to the house. The neighbours carefully lifted the burnt and lifeless body of Charles O’Donnell and brought him back into the house and laid him on the floor of the bedroom on the first floor. Above him, they placed Ellen McAllister, his sister, on the bed where she had slept peacefully with her husband and son just hours before. (18)

News of the murders spread quickly and soon became known as the Wiggins Patch Massacre.

The Aftermath

Ellen’s body and that of her brother Charles, were taken to the nearby town of Tamaqua by train for the autopsy. They were then packed in ice and stored overnight in the train station storage pens to await burial in St Jerome’s Cemetery.

The massacre shocked the region well used to violence between Molly Maguires and the mine owners.

While the police began searching for the murderers, numerous theories circulated as to the identity of the perpetrators of this heinous crime. The local Irish believed the murders had been orchestrated by the coal and Iron police or even the mine boss hired Pinkertons Detective agency as revenge for the murders of Thomas Sanger and William Uren.

One lead did turn up just after the murders. Margaret O’Donnell grief stricken at the loss of her son, daughter and unborn grandchild eventually named the local butcher by the name of Frank Weinrich as the only intruder she recognised.

The local Irish believed the murders had been orchestrated by the coal and Iron police or even the mine boss hired Pinkertons Detective agency as revenge for the murders of Thomas Sanger and William Uren

She could do this as she claimed that she saw Weinrich’s face when she clawed at him and pulled down his mask as she fought back while he was pistol whipping her. (19)

This seemed a plausible accusation as Weinrich was not only a butcher but the squadron leader of the Silliman Guards, a local militia in Mahanoy City.

As the police were controlled by the mine owners, it was no surprise that while Weinrich was questioned and held in custody for a short time he was soon released. It was rumoured a few other individuals were brought in for questioning, but no others were publicly named.

As the mine owners also controlled the local newspapers slanderous stories began to circulate denigrating the reputation of the O’Donnell’s and even the slain Ellen McAllister.

The newspapers were especially cruel in their treatment of the victims at times, minimising the tragedy and blaming the murders on the Irish themselves, using the excuse that the vigilante activity sprang from a community angered over the acts of the Mollie Maguires.

One newspaper even labelled the O’Donnell’s board house : “a place of resort for desperate characters” in which “all the parties implicated are doubtless of the very worse class … “. (20)

Margaret O’Donnell was the recipient of repeated and incessant questioning. At one point she simply could not take anymore, stating “I won’t answer any more questions.” (21)

A story began to circulate that perhaps the Molly McGuire leadership had ordered the murders as Charles and James O’Donnell had become liabilities to their cause.

This seems unlikely given the Molly Maguire leader was Jack Kehoe who was the brother-in-law of the unfortunate Charles O’Donnell and Ellen McAllister. Kehoe was a renowned family man, and it seems farfetched to think he would order the brutal murder of close family members.

It is far more likely that the killings were in retaliation for the alleged Molly Maguire murders of two local mine officials, however some historians now speculate that the attack may in part have been an attempt to smoke out Jack Kehoe and force him to commit an act for which he could be tried, and if possible, hanged. But Kehoe, was too savvy to take the bait.

What of the Pinkertons informer James McParland? Many claim he did take part in the attack, but that he was disgusted when Ellen McAllister was shot. Was it him who shouted, “we don’t shoot women”? We will never know.

What is known is that after the massacre took place, McParland sent a letter to his superiors offering his resignation. He wrote to Benjamin Franklin of the Pinkerton office in Philadelphia, saying:

“He was not ‘going to be an accessory to the murder of women and children.’ Franklin immediately wrote a letter to Pinkerton: ‘This morning I received a report from ‘Mac’ of which I sent you a copy, and in which he seems to be very much surprised at the shooting of these men; and he offers his resignation. I telegraphed ‘Mac’ to come here from Pottsville as I am anxious to satisfy him that we had nothing to do with what has taken place regarding these men. Of course, I do not want ‘Mac’ to resign.’ (22)

In the end, McParland decided to see the assignment through. Which would end with the sham trial of Jack Kehoe and his fellow Molly McGuire’s.

A spirit crying out for Justice denied

Nobody was ever charged for the murders of Ellen McAllister, her baby and her brother.

James O’Donnell fled to New York with his cousin Patrick O’Donnell and in fear of his life, he even changed his name and died in hiding. As for the McAllister brothers, James fled the area never to return and Charles was arrested soon after and charged with the murders of Sangster and Uren. He was later released due to a lack of evidence. (23)

Margaret recovered from her ordeal, but not the heartache and for the rest of her life raised Ellen’s young son and moved in with her daughter Mary, the later widow of Jack Kehoe. For Ellen, her unborn child and Charles there was no justice. There were no trials. It also appears that for Ellen there was no eternal, peace.

The boarding house was long said to be haunted by the ghost of the murdered Ellen McAllister

The Boarding house was demolished in November 2006 as it was becoming dangerous, threatening to topple onto the adjacent roadway and power lines. However, some believe that the spirit of Ellen McAllister roams modern day ruin.

Despite the demolition it is still possible to see the cellar area and remnants of foundation walls. Members of the Pennsylvania Paranormal Research Team investigated the foundation area and declared it haunted. (24)

They claimed that they were approached by the spirit of a little boy who asked to go home with them. Who was the little boy? Was he the spirit of Ellen’s unborn child? Or was the voice that of Ellen herself? Theories abound that the shock of the murderous raid, trapped Ellen’s spirit at Wiggans Patch and that she pleads each night for the bullets to stop.

Whether or not one believes in ghosts, such stories show the emotional impact of the events of December 1875. Perhaps for some, Ellen McAllister cries out for justice denied for the Irish emigrant victims of the Wiggins Patch Massacre.

In 1979, Pennsylvania Governor Milton Shapp granted a posthumous pardon to Jack Kehoe, hanged two years after the massacre. A 1970 movie titled The Molly Maguires, with Sean Connery playing Kehoe, undoubtedly helped to bring attention to Kehoe’s cause. A pardon was granted with the support of the parole board and the district attorney who stated that the “trial was conducted in an atmosphere of religious, social, and ethnic tension.” They stated the execution of Kehoe was “a miscarriage of justice.” (25)

In another act of contrition, a commemorative plaque was placed-on the wall of the Schuylkill prison cell that held Kehoe all those years ago. It is an apology and admission by the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania that he and by association the Molly McGuires died not for guilt but for being Irish, Roman Catholic, and pro-worker.

Sources:

- Shenandoah Herald (Shenandoah, PA), 11 December 1875

- Melvyn Dubofsky, Industrialism and the American Worker 1865-1920 (Arlington Heights: Harlan Davidson, 1996)

- feniangraves.net

- Melvyn Dubofsky, Industrialism and the American Worker 1865-1920 (Arlington Heights: Harlan Davidson, 1996)

- Kevin Kenny, Making Sense of the Molly Maguires (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1998

- Kevin Kenny, Making Sense of the Molly Maguires (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1998)

- Kevin Kenny, Making Sense of the Molly Maguires (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1998)

- Kevin Kenny, Making Sense of the Molly Maguires (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1998)

- feniangraves.net

- Shenandoah Herald September 1875

- Allan Pinkerton, The Molly Maguires

- 0 F.P. Dewees, The Molly Maguires: The Origin, Growth, and Character of the Organization (Philadelphia: J.B. Lippincott, 1877)

- Shenandoah Herald (Shenandoah, PA), 11 December 1875.

- Shenandoah Herald (Shenandoah, PA), 11 December 1875.

- Shenandoah Herald (Shenandoah, PA), 11 December 1875.

- Shenandoah Herald (Shenandoah, PA), 11 December 1875.

- Shenandoah Herald (Shenandoah, PA), 11 December 1875.

- Shenandoah Herald (Shenandoah, PA), 11 December 1875.

- Shenandoah Herald (Shenandoah, PA), 11 December 1875.

- The Pottsville Standard, December 11, 1875

- Shenandoah Herald (Shenandoah, PA), 11 December 1875.

- James D. Horan and Howard Swiggett, The Pinkerton Story (Putnam, 1951)

- Kevin Kenny, Making Sense of the Molly Maguires (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1998)

- The Pennsylvania Paranormal Association|The PPA

- Posthumous Pardons Granted in American History Stephen Greenspan, PhD