The Fenians: An Overview

On the 150th anniversary of the Fenian Rebellion of 1867, John Dorney gives an overview of the Fenian movement.

The word ‘Fenian’ conjures up powerful images in Irish history; of dynamite plots, clandestine meetings of secret cells plotting revolution in Ireland from both sides of the Atlantic and, of course, as a term of sectarian abuse in northern Ireland.

The movement referred to as the Fenians in fact encompasses a series of Irish Republican organisations, spanning Ireland and America dedicated to the pursuit of Irish independence from Britain, by force if necessary. The Fenians’ stated aim was an Irish democratic Republic based on universal male suffrage. They decried the ‘curse of monarchical government’ and called for ‘the complete separation of Church and state’. For this they gained the enduring enmity of the Catholic Church in Ireland, especially Cardinal Cullen of Dublin. His colleague Bishop Moriarty of Kerry famously declared that ‘hell was not hot enough’ for the Fenians.

The Fenians’ stated aim was an Irish democratic Republic based on universal male suffrage. They decried the ‘curse of monarchical government’ and called for ‘the complete separation of Church and state’.

The core Irish component of the Fenians was the Irish Republican Brotherhood, which was founded in Paris in 1858 by James Stephens and John O’Mahoney, veterans of the Young Ireland movement of the 1840s.

With the aid of charismatic recruiters such as Stephens (popularly nicknamed ‘the wandering hawk’) who also built on the previous structure of the Young Ireland movement and the rural secret societies, the Fenians built up a considerable base among urban workers and the rural poor in Ireland, recruiting up to 50,000 men by 1867.

The Fenians comprised two main movements, the Irish Republican Brotherhood in Ireland and Clan na Gael in America, both founded in 1858.

Just as important as the Irish dimension however was the movement’s presence in North America, where it was referred to as Clan na Gael. The Clan was founded in the same year as the IRB and led by some of the same people, notably former Young Irelanders John O’Mahoney and Michael Doheny, with a view to advancing the cause of nationalist revolution in Ireland.

The Clan was able to recruit thousands of young Irishmen who emigrated to America, some of whom bore bitter memories of the Great Irish Famine, others who had been exiled as result of their political activity in Ireland and others who were radicalised in America itself.

America had a number of advantages for Irish Republicans that were not present in Ireland, namely the freedom to openly fund raise and publicise for the cause of Irish freedom and also, after the end of the American Civil War in 1865, the ability to recruit thousands of Irish veterans of the war, who had military training and access to arms.

One of the stranger strategies the Fenians came up with was to launch raids on Canada from the United States in order to pressure Britain to withdraw from Ireland. Though a number of such raids were mounted, notably in 1866 and 1870, they, predictably, amounted to little in political or military terms.

The Rebellion of 1867

Less eccentric was a plan to launch an uprising in Ireland itself in 1867, sending Irish-American Civil War veterans into Ireland to lead Fenian units and infiltrating also and subverting Irish units of the British Army.

The IRB formally took a decision to launch an armed rebellion in 1865 when its newspaper The Irish People was suppressed and its organisation outlawed.

Fenian ‘circles’ became a common sight, drilling on hill tops, carrying out raids for arms and intimidating their opponents. Such was the fear of the British authorities of revolutionary ferment in Ireland in 1866 that habeus corpus was suspended and replaced by a kind of state of emergency that allowed for internment without trial.

The Rising of 1867 frightened the British authorities but in the end fizzled out in a few isolated skirmishes.

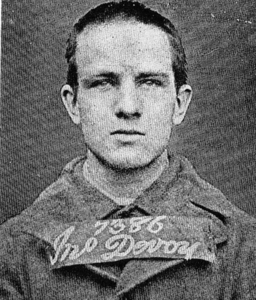

However, for all the fears of the British Government, the Rising of 1867 was a damp squib. Most of the Fenians’ leaders including John Devoy and James Stephens were arrested before the Rising. Although up to 10,000 Fenians mobilised around Ireland, notably at Tallaght outside Dublin, and although Fenians in England mounted an assault on Chester Castle, fighting in either country amounted to no more than skirmishes. For the most part, the Irish Constabulary (soon to earn the pre-fix ‘Royal’) hardly required the aid of the large British military reinforcements that had been drafted into Ireland to suppress the rebellion. Only 12 people were killed in the Fenian rebellion but thousands of Fenians were imprisoned.

There were some bloody sequels to the Rising however. A bomb in London’s Clerkenwell, aimed at freeing Fenians incarcerated in the prison there, killed 12 English civilians. In Manchester, a Fenian team successfully rescued two Fenian leaders from a prison van, but three of their rescuers, Allen Larkin and O’Brien, later known as the ‘Manchester martyrs’ were later hanged for the shooting dead of a prison guard during the incident. There was also a series of killings of suspected informers in Ireland.

Dynamite and New Departures

The Fenians did not disappear after the failure of the 1867 insurrection, but they were sharply divided on how to proceed. Both in Ireland and America there were two rival tendencies, one favouring the creation of a broad nationalist front and the other supporting continuing use of vanguard political violence.

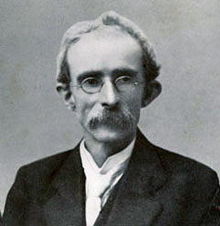

The leaders of the more political faction, notably John Devoy, President of Clan Gael in America and John O’Leary, long time President of the Irish Republican Brotherhood in Ireland, were not pacifists. Rather they concluded that there was little point in resorting to arms again unless Britain was involved in a ‘desperate European war’ and until the majority of the Irish people were explicitly on their side. In 1879 the IRB formally adopted this policy into its constitution, an initiative known as the ‘new departure’.

In the 1880s and 1890s the Fenians in Ireland and America were split between those who advocated building a mass political base and those who espoused the use of small group political violence.

Fenians, notably Michael Davitt, were to the fore in setting up the Land League in 1879 to fight for the rights of tenants farmers and many Fenians such as Davitt himself were also involved in Charles Stuart Parnell’s Irish Parliamentary Party which lobbied for Home Rule.

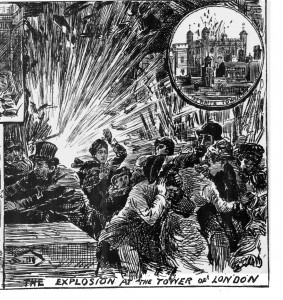

However, the movement on both sides of the Atlantic was constantly riven by splits as impatient, militant factions lobbied for action. In the 1880s, financed by an Irish-American Fenian faction known as ‘the Triangle’, a team of Fenians launched a bombing campaign in London. Though it caused considerable fear among the English public, the campaign was a failure and most of the bombers themselves were arrested.

Another splinter group funded from America, but based in Dublin was known as the Invincibles and they, at a critical moment during the agrarian agitation known as the ‘Land War’, assassinated Frederick Cavendish, the British Chief Secretary for Ireland and his Under-Secretary Thomas Henry Burke, in Dublin’s Phoenix Park in 1882. They were all later hanged.

The constant in-fighting meant that the Fenians in both Ireland and America also sometimes turned their guns on each other. In 1889 in an internal dispute in Clan na Gael in Chicago, a prominent Clan member Patrick Cronin was murdered by the ‘Triangle’ faction, bludgeoned to death and his body stuck into a sewer. Cronin had opposed the Triangle’s bombing campaigns in England (they attempted to launch another in the 1890s) and accused Alexander Sullivan of Triangle, of embezzling the organisation’s funds.

By the late 1890s, both John Devoy in America and the IRB Supreme Council in Ireland had managed to dampen down the internal splits within the movement, but ‘the Organisation’ as its members called it was increasingly directionless by the early 20th century.

A new generation

The IRB in Ireland was down to about 1,000 members by 1910 or so, but by that date it also had a new, younger, more energetic leadership. Bulmer Hobson and others were more inspired by cultural nationalism and the ideas of economic self-sufficiency espoused by Arthur Griffith’s Sinn Fein party than the Republican rhetoric popular in the 1860s. For a time they even campaigned for Sinn Fein in elections under the cover name the ‘Dungannon clubs’.

However, beginning in late 1910, the arrival back in Ireland of Thomas Clarke a veteran Fenian bomber of the 1880s who had done thirteen years in British jails, took the movement in a new direction.

By the 1900s the IRB was a smaller but still highly influential organisation. By 1910 it was again thinking about insurrection in Ireland.

With money from the Clan in the United States, Clarke founded the newspaper Irish Freedom that again called for armed insurrection in Ireland, disavowed the moderate goal of Home Rule and distanced itself from Griffith’s Sinn Fein. With the aid of his younger protégé, Sean McDermott, Clarke’s faction soon gained the ascendancy within the IRB.

When Ulster Unionists resisted the implementation of Home Rule for Ireland in 1912-14, triggering a constitutional crisis, the IRB suddenly had access to a mass nationalist movement – the Irish Volunteers, the militia founded to force the concession of Home Rule. IRB members were to the fore in creating the Volunteers and controlled many of its key positions from the start.

Another split occurred when Bulmer Hobson allowed John Redmond, leader of the Irish Parliamentary Party in to the Volunteers and Hobson was frozen out by the Clarke/McDermott faction thereafter.

The Rising of 1916 and after

When Britain went to war with Germany in August 1914, Clarke and McDermott, along with like-minded IRB members such as the recently recruited Patrick Pearse, formed a secret ‘military council’ to bring off an armed revolt in Ireland before the war’s end.

This had long been the goal of the Fenians, but in theory the Easter Rising of 1916 did not have the formal sanction of the IRB, as Clarke and McDermott went behind the back of the IRB President Dennis McCullough and one time general secretary Bulmer Hobson in order to pull it off. McCullough gave his assent at the last minute while Hobson was kidnapped at gunpoint to make sure he would not interfere.

The IRB was an important force in the Irish revolution of 1916-1923, but no longer the central driving force

Clan na Gael however, under the now aged veteran John Devoy seems to have been completely behind the rebellion and communicated with the Germans on behalf of the insurrectionists in Ireland. The Rising was not a military success but in contrast to 1867, the insurgents put up a serious fight, holding the centre of Dublin for five days before being overwhelmed by the British military and forced to surrender.

Clarke, McDermott and most of the senior IRB figures were wiped out after the Rising, mostly executed. Others such as McCullough and Hobson were discredited for their lack of support for the Rising. Furthermore, the man who took over as IRB President, Thomas Ashe, died on hunger strike after force feeding in 1917. He was succeeded by Michael Collins, a young Cork man, who remained IRB President until his death in 1922.

Technically the IRB President was also considered, inside the Organisation, as head of the Irish Republic ‘virtually established’. But the new Republican movement, based around the Volunteers and the Sinn Fein party, after their election victory in 1918, now had a mass popular base and declared their own Republic, with an elected president, in early 1919.

Throughout the subsequent War of Independence, Michael Collins and his IRB colleagues such as Richard Mulcahy, Sean O Muirthile and Gearoid O’Sullivan kept the Brotherhood alive as a means of controlling the much larger Volunteers or Irish Republican Army (IRA) and placing reliable officers in important posts.

Former IRB members including the 1919 Republic’s President Eamon de Valera, however, felt that secret societies such as the IRB had no valid role now that there were mass, open Republican organisations. Deep suspicion grew within the Republican movement over what some saw as Collins’ personal power.

A split and squalid end

When the movement split acrimoniously over the Anglo-Irish Treaty in 1922, many, including de Valera, blamed the IRB’s influence for the Treaty being accepted in the Dail or Republican parliament.

Collins and his colleagues retorted that the IRB acted as no more than a fraternal organisation for senior Republicans and that Dail had in any case, democratically decided to accept the Treaty. The IRB was split but most of its Supreme Council took Collins’ side.

In America too, de Valera fell out with the Fenian movement. John Devoy had long been used to running the Irish Republican movement in the US and when de Valera arrived in America to raise funds for the Irish Republic, Devoy refused to cooperate with him.

Whether as a result of this or because of conviction, Devoy took Collins’ side in the Treaty split and subsequent civil war. Joe McGarrity, who supported de Valera, split off to form a rival Clan na Gael that operated until the late 1930s.

The majority of the IRB supported the Treaty in 1922

Thus, rather strangely, the Fenian movement in its final years was mostly lined up, during the Irish Civil War, on the side of compromise in the pro-Treaty ranks against the intransigent anti-Treaty Republicans (though some of the latter did try to set up their own version).

The IRB mostly lapsed into inactivity after Michael Collins death in an ambush in August 1922, however the Brotherhood continued to dominate the top ranks of the pro-Treaty National Army. It was revived somewhat in late 1922 and early 1923 to counteract another factional organisation of ex-IRA officers on the pro-Treaty side, known as the IRA Organisation or IRAO.

After the latter attempted a mutiny in 1924, Richard Mulcahy, the Minister for Defence and Army Commander in Chief, but also head of the IRB faction in the Army, was forced to resign from both the government and the Army. The Brotherhood, now in disgrace among the pro-Treaty establishment, who feared it was a potentially harmful ‘state within a state’, wound itself up shortly afterwards. Clan na Gael continues to exist in various forms in the United State but never recovered its previous influence after the 1920s.

The Fenian movement pioneered the principles of modern Irish Republicanism, but its history is as full of splits and internal acrimony as great successes. Nevertheless, the movement’s influence over nearly 70 years of Irish history means they cannot be ignored.