Escaping Martyrdom in Manchester: The story of William and John Martin

By John Dorney

William and John Martin were both born in Dublin in the 1830s, sons of William Martin, a weaver and later a bookseller who lived on Chancery Place in the north inner city.

However, by the 1860s, both brothers had emigrated to Manchester in England, where they lived together and with William’s wife and children on Varley Street. William, apparently the more educated of the two, worked as clerk and later a newspaper reporter, while John was listed a ‘cooper’ that is someone who made barrels and casks.

William and John Martin were charged with, though cleared of, the murder for which three Irish prisoners were hanged in Manchester in 1867

Both were arrested in 1867 following the escape of Fenian Prisoners Deasy and Kelly and the killing of a policeman, Charles Brett during the escape, for which three men were later executed by hanging; the three, Allen Larkin and O’Brien, becoming known as the Manchester Martyrs in Ireland.

William and John Martin did not meet this fate. Their arrest was found to be erroneous and the case thrown out. But their story does tell us something of how justice was and was not done, to Irishmen accused of political crimes in Victorian England.

The shooting of Charles Brett

The Fenians or Irish Republican Brotherhood had planned an uprising in Ireland for March 1867. Arrests of their leaders had hampered their preparations and although several thousands of would-be insurgents came out to fight in Ireland, from Tallaght in Dublin to Drogheda to Cork and Kerry in the south, they dispersed after scattered skirmishes with the police and military.

In England however, the Fenians were in some respects better organised among the large, mostly working class, Irish immigrant community. They organised, just before the rising was supposed to come off in Ireland, a raid on Chester Castle, in which over 1,000 men were involved. Though the raid, an attempt to take the Castle’s arsenal and afterwards to ship the arms to Ireland, was not successful, it showed the depth and size of the Fenian organisation in the northwest of England in the 1860s.

Sergeant Charles Brett of the Manchester police was shot dead during an attempt to free two Fenian prisoners in September 1867.

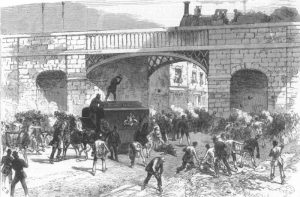

Later in the year, two Fenian leaders, Thomas Kelly and Timothy Deasy were arrested in Manchester, when found with loaded revolvers having been ‘loitering suspiciously’. A plan was put in place to free the two and on September 18, a party of as many as 40 Fenians overpowered their prison van as it escorted the prisoners from the courthouse to Gaol. Kelly and Deasy were freed (ultimately to be spirited to America), but during the scuffle, one police sergeant, Charles Brett was shot through the eye as he peered through the keyhole of the van and killed.

In the aftermath of the shooting, it seems Manchester police pulled in a wide variety of Irish suspects, 28 of whom were charged with the murder of Brett. William and John Martin were among them, charged with ‘Having on the 18th September 1867 feloniously wilfully & with malice aforethought killed & murdered one Charles Brett at Manchester.[1]

The evidence against the Martin brothers

Going on the reports of the Irish Times, it seems that William and John Martin were arrested based on the testimony of witnesses at the scene.

A report of Oct 1, 1867 stated that William Martin had been identified by four witnesses and John Martin by one.

One witness, a ‘little boy’ John Accornley, stated that he saw William Martin there, with two pistols, threatening to ‘blow out the brains of anyone who went near’. The boy said he could identify William Martin by ‘his red whiskers’.

The Irish Times on Oct 2 1867, reported that John Martin was identified as being at the scene by a bus driver, Josiah Munn, who testified that he saw John Martin, along with Allen and Maguire, throwing stones to keep the crowd back from the prisoners who had been rescued.

Numerous witnesses testified that William and John Martin were involved in the attack on the prison van.

He stated that he saw John Martin, who was wearing a ‘billycock’ (bowler hat), jump out from behind an embankment and towards the prison van.

Another witness, William Carrington, said he met the van as it was attacked. He says that he saw Allen wielding two pistols and saw William Martin, throwing stones at the van.[2]

Given the apparent abundance of witnesses, we might have expected William and John Martin to have been convicted of murder and perhaps even to have shared the fate of the celebrated ‘Manchester Martyrs’. However, it was not so. Both were discharged on November 9 1867, with the note ‘no evidence’.

‘Guided’ witnesses and reckless swearing’

It emerges across the reports that such witnesses may have been ‘guided’ by the police. John Accornley, for instance, the boy who identified William Martin by his red hair and who stated that Martin had toted two pistols during the affray, later admitted that he was told before he went to the Gaol to identify prisoners that there was a man named Martin there whom he could identify by his red whiskers.[3]

It appears from a report in the Solicitor’s Journal of 1868 that the case against the two Martins was thrown out on the grounds that witnesses gave contradictory evidence, mixing up the two men. This again would appear to indicate that the police had ‘coached’ (albeit badly) the witnesses.

Some witnesses against the Martins were found to be inconsistent, others had clearly been ‘coached’ by the police.

It seems William Martin was identified by a witness, John Beck, a railway clerk, as having been involved in the attack on the prison van and the shooting of the guard in the attempt to free the Fenian prisoners on Sept 18 1867. Beck testified that William Martin was ‘throwing stones at the police and at civilians’ at the scene.

However on the stand, it was reported that Beck, under cross examination admitted that the man he had seen throwing stones was actually John Martin .

The error was deemed ‘beyond explanation’ as ‘William Martin was no more like John Martin than Hamlet was like Hercules’.’William had rough red hair, John had smooth brown hair’. ‘William was untidy in his dress, John was the opposite’.

The report in the Solicitor’s Journal condemns the ‘reckless swearing’ (i.e. knowingly false testimony of the witness). It also criticises the practice of witnesses identifying suspects while they are chained together in police custody, which would have inferred guilt.[4]

On may surmise that the police, under pressure to achieve convictions in the aftermath of the fatal shooting of one of their colleagues, rounded up as many Irish suspects as they could and were prepared to coach witnesses accordingly. In this respect, it is strikingly reminiscent of later miscarriages of justice involving Irish prisoners in the 1970s following high profile IRA bombs in which many civilians were killed, such as the ‘Guilford Four’ and ‘Birmingham Six’.

William and John Martin were no doubt relieved to be spared ‘martyrdom’ unlike Allen Larkin and O’Brien, who were hanged.

William and John Martin must have had the good fortune to have competent legal representation, capable of pointing out the holes in the witnesses’ testimony. In all 21 of those initially charged with the shooting were discharged, testament to the shoddy work of the police and the Department of Public Prosecution in preparing the cases against them.[5]

Three were, of course hanged, but another two, Condon and Maguire were sentenced to death but reprieved, because like the Martin brothers, the witness testimony upon which they were convicted was so inconsistent.[6]

The Martin brothers, as far as can be ascertained, resumed living quietly in Manchester, no doubt pleased that they had the good fortune not to become celebrated ‘martyrs’ for Irish freedom like three of their countrymen.

References

[1] Their entry in a list of prisoners here

[2] Reports in Irish Times, Oct 1, 2 and Nov 13, 1867

[3] Irish Times Oct 1 1867

[4] The Solicitors Journal and Report Vol 12, 1868, p.23. Online here

[5] Simon Webb, Bombers, Rioters and Police Killers, Crime and Disorder in Victorian Britain. P.