The General Strike and Irish independence

How the syndicalist idea of a general strike contributed to the independence of Ireland. By John Dorney

In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, revolutionary socialists, their dreams still at that time unsullied by failure or authoritarianism, wondered how to bring down capitalism.

The urban insurrection, the preferred method of French revolutionaries throughout the 19th century seemed to be obsolete in the face of the increasingly lethal military forces possessed by the state – a risk underlined by the failure of the Paris Commune of 1871.

One of the new ideas proffered as an alternative was the General Strike. All workers would first have to be organised into One Big Union. Then on the given day, they would simply withdraw their labour, bring capitalism grinding to a halt and take over the means of production.

The general strike as proposed in the early 20th century, would bring down capitalism and establish the framework for a new socialist society.

The new faith, known as syndicalism, also envisaged the unions being the blueprint for a new democratic socialist society.

In Ireland, syndicalism was a formative part not only of socialist politics, but much more importantly, in the thinking of the new industrial unions. The most notable of these was the Irish Transport and General Workers Union, which from the start, under its charismatic leader Jim Larkin, aspired to be One Big Union for all Irish workers.

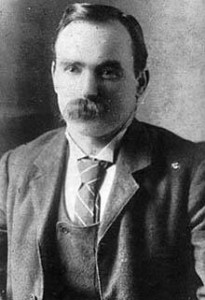

Larkin’s main lieutenant in the great strike and lockout of 1913 in Dublin, James Connolly was explicit that the general strike would one day not only bring down the existing industrial order but also shape the future, ‘cooperative commonwealth’.

Connolly on the General Strike

Writing in 1908, he argued that,

‘On the day that the political and economic forces of Labour finally break with capitalist society and proclaim the Workers’ Republic, these shops and factories so manned by industrial unionists will be taken charge of by the workers there employed, and force and effectiveness be thus given to that proclamation. Then and thus the new society will spring into existence, ready equipped to perform all the useful functions of its predecessor.[1]

The workers would refuse to transport the government’s troops or to man its services. Within a short time it would have to surrender and the triumphant workers would take over society;

‘Under a social democratic form of society the administration of affairs will be in the hands of representatives of the various industries of the nation; that the workers in the shops and factories will organize themselves into unions, each union comprising all the workers at a given industry; that said union will democratically control the workshop life of its own industry … and regulating the routine of labour in that industry in subordination to the needs of society in general … representatives elected from these various departments of industry will meet and form the industrial administration or national government of the country.[2]

James Connolly in 1908 thought that the general strike was a good alternative to insurrection.

‘The General Strike’, as envisaged like this, the millenarian uprising of the oppressed and the peaceful end of all exploitation, never took place, in Ireland or anywhere else. As an economic weapon in industrial disputes the general strike has proved cumbersome – a nuclear option- precisely because its implications are so radical.

An indefinite general strike may or may not usher in the socialist age but if strictly enforced across essential services, it would certainly bring existing society to a helpless halt within a few weeks. Thus in 1926 when British trade unions called a general strike against wage reductions, they called it off after 9 days in order to avoid fatal confrontation with the government.

But the general strike as a political weapon has proven to be highly effective. In Ireland from 1918 to 1922 there were no less than three national general strikes, called for political ends and a host of other smaller strikes, known at the time as ‘Soviets’ which combined political and economic demands. While in general these were tactical rather than revolutionary, they also as we will see, contained elements of utopian syndicalist and anti-capitalist thought.

The General Strike of 1918

The Easter Rising of 1916, the nationalist insurrection against British rule, was in many ways a throwback to mid 19th century revolutionism. A small band of insurgents – including James Connolly and his trade union based Citizen Army – took up arms, issued proclamations to the people to support them and then fought bravely but hopelessly for a week against the far superior military force brought against them.

At no time was any effort made to mobilise a mass popular movement – either by the nationalists in the Irish Republican Brotherhood and the Volunteers, or by Connolly in the form of a general strike in industry.

For the republicans the Rising was a desperate gesture of defiance in the face of mainstream nationalist support for the British war effort in 1914. This is largely true of Connolly also, who was bitterly disappointed not only with the ‘treachery’ of John Redmond and the Irish Parliamentary Party in supporting the war but also his fellow socialists in Europe’s inability to prevent it.

No general strike accompanied the Easter Rising of 1916 but in 1918 the Irish unions called a one day general strike against conscription.

In 1915 he wrote that a general strike would have prevented the bloodbath that was enveloping Europe;

‘I believe that the socialist proletariat of Europe in all the belligerent countries ought to have refused to march against their brothers across the frontiers, and that such refusal would have prevented the war and all its horrors even though it might have led to civil war … the socialist voters having cast their ballots were helpless, as voters, until the next election; as workers, they were indeed in control of the forces of production and distribution, and by exercising that control over the transport service could have made the war impossible. But the idea of thus coordinating their two spheres of activity had not gained sufficient lodgement to be effective in the emergency. [3]

In Ireland the post-Lockout weakness of the ITGWU, down to around 5,000 members by 1916 meant that no such call could have been made either, so that by the time of Easter Rising, Connolly had resolved that, ‘it may well be that in the progress of events the working class of Ireland may be called upon to face the stern necessity of taking the sword (or rifle) against the class whose rule has brought upon them and upon the world the hellish horror of the present European war.[4]

Connolly was executed after the Rising but it was in the aftermath, when the surviving union leaders, led by William O’Brien and Cathal O’Shannon, both of whom were close colleagues of Connolly, began to rebuild the ITGWU, that an Irish General Strike became a possibility. The ITGWU grew to over 60,000 members by 1918 as workers, both urban and rural, tried to bring wages up to the level of rising wartime food prices and inflation. There were 120 disputes in 1917 and 200 every year from 1918 to 1920.[5]

However, by this time Ireland was also in political turmoil. British rule had been fatally compromised by the repression unleashed by the rebellion, but even more so by the threat to impose conscription onto Ireland in the spring of 1918.

In 1914, John Redmond had been able to persuade the Irish public that supporting the war was in the interests of Ireland and of Home Rule, but by 1918, there was little appetite for more war virtually none for conscription. All the nationalist parties campaigned against it, including the Irish Party, which withdrew from Westminster in protest. The Irish Volunteers, hugely increased in numbers but largely disarmed since the Rising, prepared to resist it by force. But arguably it was the action of the Trade Unions which did most to defeat conscription.

The Irish Trade Union Congress, in particular William O’Brien and the ITGWU, called a one day general strike against the imposition of conscription and brought the country to a standstill on April 23rd, 1918, the largest strike to date in Irish history, but one which uniquely, was fully endorsed by both the employers and the Catholic Church. Everywhere outside of unionist-dominated Belfast (where a majority of workers were loyalists), the country lurched to a halt. Transport and even the munitions factories set up for the war ceased work for the day. Cumann na mBan, the republican women’s movement also called a day of protest, lá na mban (‘the day of women’) in which they urged women not to take the jobs of men conscripted for the army.

Not long afterwards the British government let the Conscription act lapse. The general strike had demonstrated that more troops would be needed to implement conscription in Ireland than would be gained from the draft. From this point onwards, the trade unions became close allies of the republican movement, which, partly because the Labour Party stood aside for them, decisively won the 1918 General election in Ireland as Sinn Fein and announced the formation of an Irish Republic.

The Limerick Soviet

A year later in April 1919, the continued potential of a republican and labour alliance was demonstrated in Limerick city. The British Army declared martial law there after shots were exchanged and an RIC constable died when the local Volunteers or IRA attempted to rescue a prisoner, Robert Byrne, who also died in the shootout.

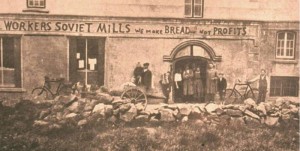

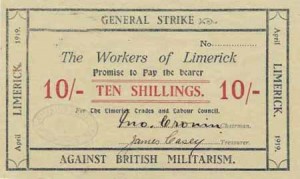

In protest against the death of Byrne, who was also an active trade unionist, and against the military curfew, which demanded that citizens carry military permits to enter and leave the city, the Limerick Trades Council called a general strike. Although localised, more so than the 1918 strike, the ‘Limerick Soviet’ as it was nicknamed, demonstrated the social revolutionary potential of the general strike. The term ‘Soviet’ at this date was popularly associated not with the authoritarian state later created in Russia and its satellites but with the workers’ committees that sprang up there during the revolution of 1917.

The Limerick ‘Soviet’ was a localised general strike against ‘British militarism’ which took over that city fro a week in 1919

The strike committee took over the running of the city for a week, boycotting the military and refusing either to transport them or to supply them with food. It printed its own money and set up its own police to keep order. Wages and food prices were set. After a week, with the Limerick business community beginning to get nervous about the intentions of the strikers, the Irish trade union leadership negotiated a compromise settlement with the British military and the strike was called off [6]

Although short lived, the ‘Limerick Soviet’ provides an intriguing example of non-violent mass resistance during the Irish revolution and also evidence that some of the syndicalist thinking of Connolly and Larkin had indeed filtered down to ordinary union activists.

The 1920 General Strike

However, the largest and most effective use of the general strike in Ireland came a year later, the third April in a row in which such a strike had been called in Ireland. Several thousand republicans had been imprisoned amid the burgeoning civil strife and growing guerrilla warfare that marked the struggle for Irish independence. In April 1920, many of them went on hunger strike and demanded to be released.

In 1920 a two day national general strike secured the release of several thousand republican prisoners.

At Mountjoy Gaol, where most of them were being held, crowds of up to 40,000 demonstrated outside for their release. Women were especially prominent, many saying the Catholic rosary. Troops at Mountjoy stood nervously behind coils of barbed wire with bayonets fixed, while in an effort to intimidate the crowd, Royal Air Force aeroplanes flew towards them at rooftop height. [7]

The trade unions, again led by William O’Brien’s ITGWU, brought Ireland to a standstill with a two day General Strike in support of the hunger strikers. In many areas workers’ committees, or ‘Soviets’, took over food supply during the strike. According to a republican source, ‘not a train or a tram is running, not a shop is open, not a public house nor a tobacconist, even the public lavatories are closed’.[8] After two days of General strike, from April 12th to 13th, the British caved in and released the republican prisoners. It was again a startling effective demonstration of the general strike’s use as a political weapon.

Union militancy continued to play an important role in republican agitation. Sometimes economic and political demands could be mixed. Laurence Nugent, Dublin IRA member recalled that in 1920 dock workers refused to export food to Britain, at once bolstering separatist politics and providing cheaper food for poor Dubliners;

‘The food situation in the city [Dublin] was still bad. Essential foodstuffs were very scarce and prices were prohibitive. Still the exports to England were increasing.Then on April 17th the dockers at the North Wall refused to load foodstuffs for England. This action relieved the scarcity in Dublin. The food position in Ireland during the years 1917, 1918, 1919, 1920 and most of 1921 was really bad. Butter, eggs, bacon, sugar and other foods were almost unobtainable. At the same time great quantities were being shipped to Britain under the British food control orders’.[9]

Railway workers also helped to paralyse the coordination of British military movements. In May 1920, they began a boycott on moving either British troops of military supplies in Ireland, restricting the military to the use of roads, which were constantly being trenched and blocked by IRA guerrillas. It was not broken until there were widespread sackings of workers in December of 1920. [10]

The strike was an independent action in imitation of the London dockers refusal to handle war material being sent against Soviet Russia, rather than a general strike. According to Irish Labour Party leader Thomas Johnson, ‘The Irish railwaymen, on their own initiative, without waiting for direction from any authority, decided not to participate in the transport of British munitions of war… ‘ .

The National Executive of the Labour Party and Trade Union Congress, according to Johnson, ‘applauded the actions of the railwaymen’ but,

‘advised caution and restraint, to prevent them from going further and faster than was advisable. Their advice, which was adopted, was that each man, when called upon to man a train carrying munitions, should act individually, and await dismissal for refusing to do duty. Instead of a general mass strike, the men were to await individual dismissal. By adopting this course, the greater part of the railway service was carried on’. [11]

It is common in left wing writing on these phenomena to condemn the conservative instincts of the Irish trade union leadership. And certainly while they advocated the use of the general strike to back the republican movement at crucial stages, they backed away from its use a social revolutionary weapon which Connolly had theorised about in 1908.

The likes of Thomas Johnson especially were moderate socialists and in their defence, the climate in Ireland by December 1920 was growing increasingly violent. Between then and the truce of July 1921, an average of 40 people a week would die in Ireland due to political violence. Continuing the railway boycott under these conditions meant exposing their members to lethal violence on the part of the state.

The 1922 General Strike

Indeed the final general strike in Ireland in the period was specifically against ‘militarism’ in the run up to the outbreak of Civil War in early 1922. In March 1922, the IRA called a Convention at Dublin’s Mansion House and rejected the Dail or Irish Parliament’s decision to accept the Anglo –Irish Treaty that dissolved the Irish Republic and inaugurated the Irish Free State as part of the British Empire. In April, a hardline faction of the anti-Treaty IRA occupied the Four Courts in central Dublin in defiance of the Provisional Government.

In 1922, in protest at the anti-Treaty IRA’s defiance of elected authorities, the unions called a third and last general strike against ‘militarism’ in general.

This was a time when class conflict was sharpening. In the absence of effective state authority, social conflicts took on a violent intensity. In the rural west, attacks on landlords and ‘ranchers’ spiralled. In the south east, workers occupied agricultural cooperatives and raised the red flag[12]. In an echo of 1920 ‘Soviets’ were formed around the country as workers protested against falling wages.

The context to this unrest was an international economic recession, in which the value of agricultural exports had fallen by as much as 50%. In Leitrim it was reported that 1922, was the ‘Worst year for farmers since ’47 [the famine year]’. In that county £20,000 in rates went uncollected.[13]

The recession meant that farmers and their workers in particular clashed as the former tried to bring down wages. The Monaghan Farmers’ Union reported that – ‘The farmer goes to work with a revolver in one hand for the time to come’. In the south, ‘houses have been burnt, farm produce has been burnt’. The farmers urged, the Irish government to ‘fight their battles for them’. ‘Farmers may have to fight labour’, they warned. [14] The Irish Civil War of 1922-23 could conceivably also have been a class war.

However at this point, the link between the republicans and labour, forged in 1917-20 was broken. In April 1922, in protest at the IRA’s rejecting the vote of the Dáil, the unions, which had declared general strikes against the British in 1918 and 1920, called one against ‘Militarism’ and the threat of civil war. It was generally understood that this was particularly targeted against the anti-Treatyites. Only a small rump of socialists led by James Connolly’s son Roddy, in the newly formed Communist Party of Ireland, publicly backed the republicans.[15]

The General strike of 1922 was widely applauded by the pro-Treaty government by the press the Catholic Church and by society generally. For this it has been widely condemned by historians of a left wing or republican persuasion. However, from the point of view of the union leadership, they had called general strikes in favour of Irish democracy in 1918 and 1920 and were now doing so again.

The Free State government was no particular friend of organised labour. During the Civil War, strikes such as the Postal strike of September 1922 and the agricultural workers’ strike in Waterford in the summer of 1923 were put down with military force – deemed as they were to threaten the security of the new Irish state. An Army unit, the Special Infantry Corps, was raised to put down social and agrarian agitation.

Nevertheless the Labour Party, though it protested against the harsh repression of 1922-23, was satisfied to remain as a loyal, democratic opposition.

The brief window of 1918-22, which had seen the widespread use of the general strike and to some extent encouraged the dreams of a cooperative society, was over.

References

[1] James Connolly, Socialism Made Easy, 1908.

[2] James Connolly, The International Socialist Review, October, 1909.

[3] James Connolly, Revolutionary Unionism and War, International Socialist Review, March 1915.

[4] James Connolly Can Warfare be civilised? The Worker, 30 January 1915. (My thanks to the oline Marxists writers archive section on James Connolly, located here)

[5] Conor Kostick, Revolution in Ireland, p35

[6] Liam Cahill, the Forgotten Revolution, Limerick Soviet 1919

[7] Padraig Yeates, A City in Turmoil, p112

[8] Kostick, Revolution in Ireland, p132-135

[9] Laurence Nugent BMH WS 907

[10] Ibid. p141

[11] Thomas Johnson Ws 1,755 BMH

[12]Niall C. Harrington, Kerry Landing August 1922, An Episode of the Irish Civil War, p21

[13] Anglo Celt April 25 1922

[14] Anglo Celt January 28 1922

[15] Charlie McLure, Roddy Connolly and the Struggle for Socialism in Ireland, Cork University Press 2006, p52