Commemorating the Lockout

John Dorney reports on the 1913 Commemoration Committee – gearing up for the centenary of the Dublin Lockout of 1913.

It will be 99 years this August since the start of the great Dublin Lockout, when members of Jim Larkin’s Transport Union walked off the trams of the Dublin United Tramway Company, on strike for recognition of their union.

It was a social confrontation almost unique in modern Irish history. William Martin Murphy, owner of the tram company and the Irish Independent newspaper not only wanted to purge his companies of ITGWU members, he formed a cartel of virtually all the employers of Dublin to do likewise. Larkin and the other unions in the city refusing to concede to a pledge to forswear union membership, brought out over 20,000 men and women on strike. Some terms in history are undervalued by overuse, and one of them is ‘class war’, but there could be no other term for the bitter ensuing struggle.

Over 20,000 workers went on strike or were locked out in a dispute over union recogntion

The employing and employed classes butted heads for six months until sheer hardship forced the union members resentfully back to work, taking a humiliating pledge not to belong to or associate with Larkin’s union. The workers were sustained with food and money from trade unionists in Britain while the middle classes of Dublin held collections for the ‘loyal workers’, or strike breakers.

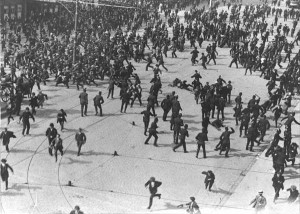

The dispute was also famously bloody. The Dublin Metropolitan Police fought pitched battles all along the tram lines with strikers and at one point drunken policemen made a night time assault on a tenement building to exact revenge on those who had been rioting during the day. A union rally on O’Connell Street was violently broken up, in an episode remembered in the labour tradition as ‘Bloody Sunday’ – though in fact many of those baton charged were mere bystanders. Three union members were beaten to death over the first weekend of the strike.

The workers’ self-defence force, set up during the strike – the Citizen Army – went on to participate in the nationalist insurrection, the Easter Rising just three years later. Some of its members later spoke of it as a chance to pay back to the police what had been done to them in 1913.

The Lockout fits awkwardly into the mainstream narrative of Irish history. The workers were generally nationalists, but so too were many employers, including William Martin Murphy. The strikers’ greatest ally was the British Trades Union Congress without whose aid the strike could not have been sustained. The British government did deploy police and troops to ‘keep order’ but they were in fact far more conciliatory to the workers than were Irish employers.

The Lockout fits awkwardly into the standard narrative of Irish history, but it exposed many of the contradition apparent in independent Ireland.

Some aspects of the dispute seem to be a preview of features of independent Ireland. The entrenched privilege of the Irish media, defending their own class interests with calumny of their opponents seems familiar even now. The Catholic Church also flexed its muscles – forbidding the union’s plan to send children to socialist households in England for the duration of the strike, lest they be exposed to irreligious influences.

The Lockout was also a rare time when Ireland was at the centre of broader European trends. The years before the First World War saw waves of strikes across western Europe and saw the consolidation of mass union organisations in many countries.

Although in the short term it was a defeat for the ITGWU, in the longer term the 1913 struggle is seen by labour activists as a kind of founding myth – a heroic sacrifice that helped to found their movement. Larkin’s ITGWU is the ancestor of SIPTU, the largest union in Ireland today. Although, as Padraig Yeates, the director of the 1913 commemoration committee jokingly remarks, 100 years later the fight for union recongition is still ongoing. ‘It’s like when Lincoln freed the slaves in 1862 and it was the 1960s before full civil rights for black Americans was achieved’, he says.

The iconic status of the 1913 strike in labour memory can be seen on the banners, now being collected in Liberty Hall by Sam McGrath and Kevin Brannigan of the commemoration committe. The dark navy banner of the ITGWU No 19 Branch, for instance, reveals layers of working class Dublin identity. Alongside the union emblem are the symbols of the four Irish provinces and also of Dublin itself. Under an embroidered image of workers being baton-charged in 1913 are portraits of the ‘Lockout martyrs’, ‘Murdered on the Streets of Dublin’ and under that, ‘Ni saoirse gan saoirse na lucht oibre’ – ‘no freedom without freedom for the working people’.

Among the commoration events planned are tapestry, a display of historic banners and an oral history project

Other banners reflect militancy from further afield. One commemorates ‘those who suffered in the Cork General Strike of 1870’. Another, bright red, with five hangman’s nooses, is a tribute to the Molly Maguires, Irish miners hanged in Pennsylvania in 1877. One of the more off-beat, a banner representing health workers, depicts an arch-angel Gabriel slaying Satan. A representative mix of the eclectic nationalist, socialist and religious influence on Irish labour politics perhaps.

A tapestry, after the style of the Bayeux Tapestry, is planned to depict the Lockout, also in the works are an oral history project to recover grassroots memory of the dispute and a community archeology project.

It is important, Padraig Yeates, argues that the union commemoration of 1913 not be overshadowed in the upcoming, so-called, ‘decade of commemorations’ which will mostly remember the events that led to Irish independence and partition. Not only was the social convulsion of the Lockout dramatic, but it exposed many of the contradiction that had to be worked out, often painfully, in independent Ireland.

You can visit the 1913 Commemoration Committee’s site here.

You can listen to Padraig Yeates speak about the Lockout here and here.