‘Defacing our Deliverer’, The history of the William of Orange statue in Dublin

By John Dorney

College Green in Dublin city centre was once the centre of the Protestant Kingdom of Ireland. On one side stood the Parliament building, constructed in the 1730s (now the Bank of Ireland) and at the head of the street, Trinity College, the Protestant University, founded back in 1592.

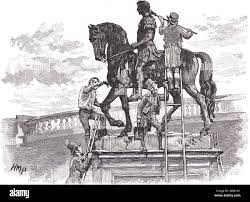

Facing them, once, was a statue of William of Orange, the hero and ‘Deliverer’ of Protestant Ireland. The statue depicted William as a conquering hero, sat astride his horse, sword at his side, dressed in the garb of a Roman emperor.

It was first erected in 1701 to commemorate William’s victory over King James at the Battle of the Boyne in 1690 and so the Williamite or Whig narrative went, securing the Protestant religion and civil liberty for his subjects in Ireland.

Dublin’s mostly Protestant population celebrated William’s victory at the Boyne in 1690 with relief.

In those days, Dublin was a majority Protestant city. It had been since the wars of the 1640s and 50s when Catholics were expelled from the city during the English Parliamentarian or Cromwellian regime. David Dickson writes ‘in 1644 Protestants for the first time formed a majority of the much shrunken urban population’ (68% of a population of about 8,000). By 1660, Protestants made up about 80% inside city walls [1] and in the first half of the following century, they would be nearly 70% of a population of about 150,000 people. [2]

Catholic Jacobites briefly repossessed Dublin in 1689-90 during the war between King William and King James, holding their own parliament there which demanded freedom of religion, restoration of confiscated Catholics lands and autonomy of Ireland from England. Among other things, during their rule over the city, they also took over Christchurch Cathedral for Catholic worship and closed down Trinity College, using it as an army camp and then a holding centre for Williamite prisoners.[3]

When William defeated James’ army at the Boyne therefore and James himself fled for France and his forces abandoned Dublin and William’s English, Dutch, Danish and Irish Protestant army marched into the city without a fight, it was no surprise that Dublin’s Protestants celebrated his arrival. One Protestant diarist wrote that ‘we crept out of our houses and found ourselves as if it were in a new world’.[4]

The Statue of ‘the Deliverer’

At William’s first birthday after the Boyne (November 4 1690) the authorities held a banquet in Clancarty House (formerly seat of a Jacobite notable) fireworks and celebratory gunfire echoed on College Green and a ‘hogshead of claret’ was set up on the street so that the common people could ‘drink the health of William and [his wife] Mary’.[5]

The equestrian statue itself was commissioned in 1700, by the lord mayor of Dublin, a Dutch merchant by the name of Bartholomew Van Homrigh, hiring the renowned artist Grinling Gibbons and opened in 1701.

Inscribed on the statue, in Latin, was an ode to William as the ‘saver of religion’, the ‘restorer of laws’ and ‘assertor of Liberty’. This was how William was seen, especially by ‘Whigs’ throughout the Three Kingdoms of England, Scotland and Ireland, as the man who had saved them from Catholic and absolutist tyranny. In Ireland of course, this had an added resonance as the Protestants comprised no more than 20% of the population in a majority Catholic country and many believed that in the case of a Jacobite victory they would have lost their property and even their lives to the vengeful Catholics.

The statue in College Green depicted William as a conquering Roman emperor and lauded him as the ‘saviour of religion’ and the ‘assertor of liberty’

For most of 18th century, William’s victory at Boyne was popularly celebrated by Irish Protestants on July 1 and the battle of Aughrim of 1691 was also the occasion of raucous bonfires on July 12th (it was not until the 1790s that the Boyne took over as the subject of commemorations on July 12). The state commemoration, however, in the eighteenth century was on November 4, William’s birthday, marked by a military parade past the statue by the Lord Lieutenant (essentially governor) of Ireland, which was seen as a celebration of the ‘Revolution of 1688’, ‘liberty; and the ‘Protestant constitution’.

The parade was given added significance by the presence of the Irish Parliament building there from the 1730s, William’s victory being seen as upholding the power of parliament against absolutist ‘arbitrary government’.

Catholics and Jacobites were not the only ones who disliked the statue and what it represented, however. So did ‘Tories‘ who supported the power of the monarch and the High (Anglican) Church and disliked the ‘Whigs’ who celebrated ‘resistance to tyranny’, ‘liberty’ and the power of parliament.

Tory students from Trinity College damaged the statue in 1710. Some considered it as a ‘studied Whig insult’ that the backside of William’s horse faced the front gate of Trinity. The two undergraduates responsible for the 1710 defacement were fined £100 each, sentenced to six months’ imprisonment and made to stand in front of the statue with placards reading, ‘I stand here for defacing the statue of our glorious deliverer, the late King William’.[6]

Whigs and patriots

A great irony of Irish history is that the Irish Whig tradition, who were generally more fiercely Protestant and more anti-Catholic in early 1700s, morphed into the ‘Patriots’ of late 18th century who advocated ‘relief’ for Catholics and more self rule for Ireland. Whereas the Tories, on the other hand, (once allies of Catholic Jacobites) evolved into the supporters of ‘ultra-Protestant’ reaction.

The Irish Whigs, famously led by Henry Grattan (whose statue now itself stands in College Green), saw themselves as still upholding the ‘liberty’ won in the ‘revolution of 1688’ by agitating for thoroughgoing reform of the Kingdom of Ireland in the late 1700s.

It seemed natural for the original Irish Volunteers (formed in 1778, initially to defend against a feared French landing during the American revolutionary war) and Grattan’s Patriots, to hold their famous rally in 1779, demanding more self government and free trade for Ireland, at the statue of William.

Grattan’s ‘patriots’ rallied in front of the statue, demonstrating for ‘liberty’ in 1779

In fact the occasion for the rally, immortalised in Francis Wheatley’s painting, was William’s birthday on November 4, in which the Lord Lieutenant and a regiment of regular troops were supposed to march from Dublin Castle past the statue.

Instead, on this occasion, some 10,000 Volunteers paraded from Stephen’s Green to College Green ‘upstaging’ the Lord Lieutenant and at the statue hung placards reading ‘The relief of Ireland’, ‘The Glorious Revolution’ and ‘Free trade – or else’.[7] In the subsequent ‘Revolution of 1782’, Grattan’s party achieved much of their agenda, including not only ‘relief’ for Catholics but also assuring the Irish parliament of the sole right to legislate for Ireland.

It is a reminder that modern Irish nationalism bears a paradoxical debt, at its foundation, to intellectual heritage of the victory of King William in 1690, or at least to how this was subsequently interpreted.

A ‘party’ symbol

But by 1790s, the statue of William in Dublin was taking on a darker, more sectarian hue, especially after the founding of the Orange Order in 1795, in south Ulster but which soon had a strong presence in Dublin too. William now represented ‘Protestant Ascendancy’ over Catholics as well as conservative hegemony over democratic reformers and revolutionaries.

Revolution, not reform was in the air, with the Society of the United Irishmen – initially advocates of radical reform, but after their banning in response to their support for revolutionary France, dedicated to the founding of a secular, revolutionary republic – plotting insurrection.

The Orange Order in Dublin, interpreting William’s statue in a much narrower sense than the Whigs, as representing solely a Protestant victory over ‘Popery’, took to holding rallies at it and to decorating the statue with Orange ribbons, which according to one observer, ‘every well wisher of peace and order would be pleased to have discontinued’.[8]

From the 1790s onwards the statue became a highly partisan symbol in a majority nationalist city with strong Orange tradition.

For by this time, Dublin had, as well as a lively radical political underground, again a Catholic majority among its roughly 250,000 inhabitants; a result of rural migration to the city during the second half of the eighteenth century.

As a result, the statue became a target anew for enemies of the established order in Ireland. In 1798, the year of the United Irish rebellion, William’s sword was removed and an attempt made to saw off the head. Further attacks were made on the statue in 1805, reportedly by supporters of Robert Emmet’s failed rebellion of two years before and in 1837, the latter mostly likely by supporters of Daniel O’Connell – the populist Catholic leader who campaigned for full legal equality for Catholics and the return of the Irish Parliament, abolished in 1801.[9]

But the statue tells us more also about the tortuous ironies of Irish history. The Orange Order and many ‘ultra-Protestant’ partisans opposed the Act of Union initially as it promised to give equal rights to Catholics in a United Kingdom. As a result, the British state (though it had found the Orange movement useful in suppressing the rebellion of 1798) subsequently disassociated themselves from the Orange tradition and even from King William himself.

The state parade to the statue on William’s birthday (November 4) was discontinued under Union in 1806, being seen as too divisive (a ‘party demonstration’ was the terminology of the time) by the Lord Lieutenant, John Russel, Duke Bedford, who wished to be seen as a conciliatory, reforming figure.[10] In the 1820s, Dublin Orangemen, much to their chagrin were forbidden by the Lord Lieutenant from parading past the statue of King William on July 12, causing a riot at one of the city’s theatres in response.[11]

The statue’s decline

Dublin was changing. Daniel O’Connell was elected Lord Mayor in 1841, the first Catholic to hold the position since 1689, after municipal elections were reformed in 1840 so as to give all male property holders (and not just the Protestant dominated ‘Freemen of the City’) the vote.

O’Connell magnanimously had the statue of William given a new coat of bronze paint but the statue suffered further after mostly Catholic nationalist Home Rulers came to dominate the city government from the 1880s. The Home Rulers allowed the statue to deteriorate and rarely had it cleaned. They also, however, refused an offer from Belfast to have the statue moved there.[12]

By the early twentieth century, the city’s political identity was overwhelmingly nationalist. In a rally on St Patrick’s Day (March 17), 1916, in hindsight a dry-run for the Easter Rising of a month later, the Irish Volunteers marched to College Green and were addressed by their leader Eoin MacNeill from beside the statue of King William, though they may have wished to channel the spirit of the Volunteers of 1779 rather than that of William himself.[13]

Nevertheless the statue survived the 19th century and even the Irish revolutionary period (1916-1923) when many of Dublin’s finest buildings were destroyed in open combat and political violence (in which over 1,000 people lost their lives in the city).

The statue was blown up by the IRA in 1928 on Armistice Day.

The statue could not however, survive the aftershocks of Irish independence, in which Irish republicans often sought to eradicate the symbolic presence of ‘imperialism’ from Dublin and elsewhere. A great many Dublin monuments, including one of King George II on Stephen’s Green and Field Marshal Hugh Gough in the Phoenix Park as well as the column in honour of the admiral Horatio Nelson on O’Connell Street fell to republican explosives over the following half century.

In 1928, on Armistice Day, November 11, the statue of William was blown up by the IRA. It was a part of a campaign by republicans, casting about for ways to remain relevant following their defeat in the 1922-23 Civil War, against Armistice Day in Dublin in which the Union flag was flown and ‘God Save the King’ sung by war veterans and unionists. On the same day, another bomb was placed at the statue of King George on Stephen’s Green. Rioting also took place between republicans and Poppy wearers in the city centre.[14]

The statue was so badly damaged that it was removed by Dublin Corporation the following year, 1929, and its head was later removed from a city repair yard by armed men.[15]

To Irish republicans of the 1920s, no doubt, King William’s statue represented a purely negative symbol; of the conquest of Ireland by English forces in the 1690s and more latterly, the hero of what they viewed a sectarian and anti-Catholic state in Northern Ireland that had existed since 1920.

So ended the 227 year history of King William’s statue in College Green. In 1966 it was replaced by a statue of Young Ireland leader Thomas Davis, first mooted in 1947 finally erected, designed by Edward Delaney, in 1966.

Thomas Davis was, like William of Orange, a Protestant, but also an advocate of Irish independence and of the revival of the Irish language. This was a symbol that the twentieth century Irish state could live with more comfortably.

If you enjoy the Irish Story and wish to support our work, please considering contributing at our Patreon page here.

References

[1] David Dickson, Dublin Making of a Capital city (Kindle version, 2014), p.68, 76

[2] Toby Barnard cites a Hearth Tax census of 1732, which showed that 68% of Dublin city’s population was Protestant by that time. (Barnard: ‘A New Anatomy of Ireland, p.2)

[3] Dickson, Dublin, p.101

[4] Dickson, p.104

[5] Maurice Craig, Dublin 1660-1860, The Shaping of A City, Liberties Press 2006, p.102

[6] Craig, Dublin, 1660-1860, p.103

[7] Dickson, p.199

[8] John Wharburton, A History of the City of Dublin from earliest Accounts to the Present Day, Vol 2. (1818) P.1098-1099

[9] The attacks are catalogued here: https://www.dublincity.ie/library/blog/statue-king-william-iii

[10] Dickson , p.297

[11] Craig, p.331

[12] https://www.dublincity.ie/library/blog/statue-king-william-iii

[13] Dickson, p449

[14] Fearghal McGarry, ‘Too Damn Tolerant’, Republicans and Imperialism in the Irish Free State, in Republicanism in Modern Ireland, UCD Press 2003 p.66

[15] Ibid.