Robert Emmet, the 1803 Proclamation of Independence and the ghost of 1798

Maeve Casserly examines the thinking of Robert Emmet, architect of the 1803 rebellion.

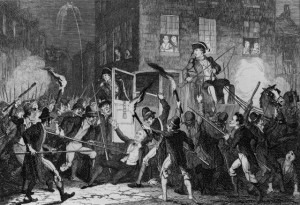

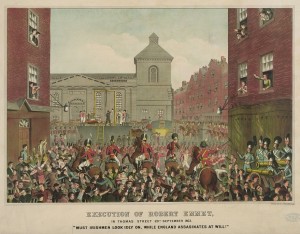

In 1803 in Dublin, Robert Emmet and a small band of republican revolutionaries proclaimed the independence of Ireland. After a haphazard rebellion, that turned out to be little more than a calamitous, bloody riot on Dublin’s Thomas Street, his hopes lay in ruins. Emmet, after fleeing to a safe house in the Wicklow mountains, was subsequently arrested, tried for treason and put to death along with 15 of his followers.

Why would the young Emmet, a man of talent and ambition, have put his name to such an ignominious failure? The answer lies in the long shadow cast on the young revolutionary by the much larger, bloodier, but also unsuccessful uprising of 1798

And those who were laid at rest,

Oh! Hallowed be each name;

Their memories are forever blest –

Consigned to endless fame.Robert Emmet, Arbour Hill. Unknown Date.

This poignant ode to the veterans of the 1798 Rebellion is an example of the truly profound affect that the ’98 Rebellion had on the young Robert Emmet, and, consequently, his own revolutionary attempts. The impact of the ‘Myth of ‘98’ on the formation of Emmet’s own politics and ideology cannot be overstated, especially within the framework of his relationship with the United Irishmen [Emmet’s older brother, Thomas Addis Emmet, was a senior member of the United Irishmen in the 1790s, and was arrested and imprisoned in Scotland for his part in the failed rebellion].

The impact of the ‘Myth of ‘98’ on the formation of Emmet’s own politics and ideology cannot be overstated, especially considering the involvement therein of his older brother, Thomas Addis Emmet

This influence is particularly obvious when looking specifically at Emmet’s connection with the veterans of 1798. It is also evident in Emmet’s changing views on the need for French military aid during the two year period he spent in France, between 1800 and 1802, where he associated both with the Irish exiles and the French military government.

To demonstrate the influence of 1798 on Emmet, it is useful to draw from the text of the the 1803 Proclamation of the Provisional Government itself. Its highlights the overarching feeling of bitterness which Emmet felt as a result of his contact with the veterans of 1798, their treatment by the British government, and his attempts to secure French military aid. While the rousing language of Emmet’s famous speech from the dock have been the subject of extensive research and discussion, the lesser known 1803 Proclamation is equally as significant in revealing the political and ideological implications of 1798 on Emmet.

The contextual analysis of the 1803 Proclamation will concern the time period immediately following the 1798 Rebellion and up until the 1803 Rising itself, particularly focusing on the preparations and motivations of Emmet surrounding the insurrection. This essay will explore three main points: firstly, the overarching feeling of betrayal and bitterness among Emmet and the 1798 veterans following the Rebellion and its aftermath.

Loss of confidence in France

The wording of the Proclamation exposes Emmet’s feelings of betrayal in the wake of 1798, and his consequent clandestine restructuring of the United Irishmen. The Proclamation also demonstrates his ideological shift towards an autonomous insurrection for Irish independence.

It is, however, important not to ‘read history backwards’. Emmet’s 1803 Rising was not an inevitable outcome of the failure of 1798. As late as 1802, when Emmet was preparing to journey home to Ireland from his self-enforced exile in France, he still was not sure what he would do upon his return.

Like Tone and the United Irish leadership, Emmet initially put great hope in fraternal aid from revolutionary France. The period of the late 1790s was a time when the idea of the nation at arms, that is, the fusion of the nation state, independence and war, all became intrinsically linked. The opening paragraph of the Proclamation neatly summarises Emmet’s belief in Irish independence; ‘You are now called upon to show the world that you are competent to take your place among the nations . . . as an independent country.’[1] In the confused context of the first years of the Act of Union in Ireland, when national identities were still defined by the Franco-British conflict, these words demonstrate the impact of 1798 on Emmet.

By 1803 Emmet had given up hope of military aid from revolutionary France

In much of the scholarship surrounding the strategic alliance of France and Ireland, historians have often concluded that it was one of ‘abject failure.’ This has resulted in an ‘over-concentration on the outcome [of the alliance] and not the process itself.’[2] Emmet’s time in France can however, be seen as a positive experience. It was here, in his ‘host country’, that Emmet solidified his belief in Ireland as ‘une nation, un peuple [‘a nation a, a people’].’[3]

In historian Thomas Bartlett’s discussion on confused identities and allegiances in the aftermath of the 1798 Rebellion, he points to the increasing socio-cultural manifestations of Britishness in Irish everyday life and consequently an almost subconscious distancing from France. This detachment from France was heightened by the failure of the 1798 Rebellion.[4] Emmet’s provocative words in the 1803 Proclamation, attest to this new ideological stance which was profoundly influenced by his time in France and his association with the exiled veterans of 1798.

The change in relationship with France is apparent in the following words, ‘[the Rising will be fought] without the hope of foreign assistance. [5] It is significant that Emmet uses the word ‘hope’ rather than ‘help’ here, as by late 1802 and his return to Ireland, Emmet had all but given up on the promise of French aid. In the Proclamation Emmet alludes to his new political stance towards France and his aversion to a French invasion as a result of the failures of 1798, ‘That confidence which was once lost by trusting to external support . . . has been again restored. We have been mutually pledged to each other to look only to our own strength.’[6]

This section may also reflect his awareness of a devastating meeting in Paris on 30th May between his brother Thomas Addis, in exile after his release from Fort George in Scotland in 1802, and General Berthier. During this meeting the French minister revealed that the navy might not be ready to assist the United Irishmen for a further six months. As the 1803 Rising had been planned to take place in June 1803, this late notice of the postponed French military aid only served to further reinforce Emmet’s view of the need for a distancing between the Irish rebels and the French government.

Secretive military tactics

The United Irishmen, once an open and popular mass movement, had transformed by necessity during the 1790s into an underground elite. The high level of clandestine conspiracy, Emmet’s extensive use of codes, invisible ink, aliases and severe lack of documentation available from this period, are all symptomatic of Emmet’s fear of informers as a result of the experiences of the veterans of 1798 during the Rebellion.

‘If the secrecy with which the present effort has been conducted shall have led our enemies to suppose that its extent must have been partial, a few days will undeceive them.’

The Proclamation illustrates Emmet’s belief in highly secretive military tactics, ‘If the secrecy with which the present effort has been conducted shall have led our enemies to suppose that its extent must have been partial, a few days will undeceive them.’[7] In his analysis of Emmet’s military tactics, historian Patrick Geoghegan concludes that, ‘the blueprint [for 1803] was an extra revolutionary programme, fully justifying Emmet’s reputation for military planning . . . successfully combined elements of guerrilla warfare and street-fighting, and displayed a masterful grasp of the requirement of battle.’[8]

Emmet’s confidence in his abilities as a military strategist is shown in the bold statement, ‘Nineteen counties will come forward . . . neither confidence nor communication are wanting.’[9] The Proclamation reveals Emmet’s belief that both military tactics as well as rebellious spirit had improved in the years following the failed 1798 rebellion.

‘Men of Leinster! . . . to the courage which you have already displayed is your country indebted . . . but . . . if six years ago you rose without arms, . . . what will you know effect, with that capital, and every other part of Ireland, ready to support you?’[10]

Here Emmet refers not only to the veterans of 1798 and flatters their previous courage, but he also references the improvements in military tactics and his optimistic ideas of how many men on the ground would actually support the rising. By stating that, ‘Accused by your enemies of having violated that honour by excess . . . the opportunity for vindicating yourselves is now . . . by carefully avoiding all appearance of intoxication, plunder or revenge,’ Emmet wishes to put forward the image that the new United Irishmen are more professional, trained soldiers, and more disciplined that those of 1798.[11]

The influence of Emmet’s keen studies of the military tactician Colonel Templehoff, who emphasis the need for the element of surprise, is apparent in the following statement, ‘We had hoped . . . to have taken them by surprise . . . though we have not been altogether able to succeed’[12] This is a reference to the unfortunate explosion in the Patrick’s Street depot on July 16th 1803, which Emmet felt took away the vital element of surprise.

Social radicalism and the memory of repression in 1798

The Proclamation also contains allusions to the widening of the political agenda of Emmet and the United Irishmen following the failure of 1798. Thomas Russell, a highly influential veteran of 1798 and radical campaigner for economic and social reform, is a key influence on Emmet here. An important example of this is the stipulation that, ‘tithes [taxes to the established Church] are forever abolished.’[13]

In addition to democratic parliamentary reform, the 1803 Proclamation announced that tithes were to be abolished and church lands nationalised

The historian James Quinn proposes that here Russell may have had some say in the measures proposed in the revolutionary Proclamation of 1803. In addition to democratic parliamentary reform, the Proclamation announced that tithes were to be abolished and church lands nationalised, although its social measures probably did not go as far as Russell would have wished.’[14]

The 1803 Proclamation thus demonstrates that the United Irishmen had to redefine and broaden their programme, ‘involving a widening of range of grievances . . . and an ability to politicise poverty’ as a result of the failures of the 1798 Rebellion.[15]

The Proclamation expresses Emmet’s feeling of bitterness following his impression of the British government and the techniques it employed in dealing with the rebels of 1798 and the widespread violence in the countryside, ‘The first introduction of a system of terror, the first attempt to execute an individual in one country, should be the signal of insurrection in all.’[16] Emmet, uses the people’s experience of repression in this ‘system of terror’ as a call to arms.

It is important to remember that during this time the Irish Yeomanry and militia had acquired a reputation for indiscipline and sectarian violence. In Wexford, between the years 1798 to 1801 the local yeomanry corps were almost certainly behind the epidemic of chapel burning that resulted in some thirty chapels going up in flames.[17]

This sentiment from the Proclamation demonstrates Emmet’s belief that not only were the post-1798 methods of repression employed by the British government unjust and immoral, but that there was also a deep seated resentment among the Irish people that no foreign country, that is, the French Republic, came to Ireland’s aid.

‘Shake off your slumber and oppression!’

The Proclamation is also important in demonstrating Emmet’s relationship with rebels in the North of Ireland and their significance in the 1803 rising, ‘We call upon the North to stand up and shake off their slumber and their oppression.’[18]

The Proclamation is also important in demonstrating Emmet’s relationship with rebels in the North of Ireland and their significance in the 1803 rising, ‘We call upon the North to stand up and shake off their slumber and their oppression.’[18]

In the recruiting of men following the 1798 uprising, Emmet and the United Irishmen tried to lower the sectarian temperature of their announcements in order to ease Catholic-Presbyterian tensions in mid-Ulster and make possible renewed United Irish recruiting there. Thomas Russell, the only United Irishman whose career spanned the founding of the society and the insurrection of 1803, was a key figure in the North in the drafting of both new men and reluctant veterans of 1798.

Emmet appealed in vain for areas of Ulster and Leinster which had been active in 1798 to join his insurrection

Emmet, who was anxious to recruit as many experienced veterans as possible, summoned Russell back to Ireland, from his enforced exile in France, and gave him the task of raising Ulster. In July 1803, Russell travelled to former United Irish strongholds throughout Antrim and Down. But almost everywhere he was greeted with apathy or even hostility. The political situation in Ulster had changed dramatically in the seven years of Russell’s absence, during which time its enthusiasm for a renewed rising had been dampened by the lurid accounts of sectarian atrocities that had occurred in the south in 1798, and the ‘sight of France becoming yet another plundering imperial power.’[19]

A Popish plot?

‘Whomsoever presumes . . . that this is a religious contest, is guilty of the grievous crime [of misunderstanding]’.[20] Here, Emmet underlines his awareness of sectarian clashes, and by removing the subject of religion, attempts to quell conservative Protestant fears and give the rebellion a universal appeal. Historian Kevin Whelan stresses that responses to the rebellion in print developed with remarkable rapidity.[21]

‘Whomsoever presumes . . . that this is a religious contest, is guilty of the grievous crime [of misunderstanding]

The first of these portrayed 1798 as the result of a deep-seated popish plot with tentacles stretching all the way to Rome and embedded in Irish history. It sought to establish parallels between the rebellions 1641 and 1798, and to depoliticise the history of 1790s. The classic viewpoint of this formulation was Sir Richard Musgrave’s Memoirs of the Various Rebellions in Ireland.

The first edition of this, which was published simultaneously in London and Dublin in March 1801, sold out its 1,250 print-run in two months. The book’s enormous vogue among ultra-loyalists produced an equal and opposite vilification from radicals.[22]

Emmet’s attempts to address the sectarian politics in the period following the 1798 Rebellion are evident in the following sentiment, ‘We are not against property – we war against no religious sect – we war not against past opinions or prejudices – we war against English dominion.’[23]

Despite his attempts to give the Rising a universal appeal, Emmet’s insurrection was still plagued by religious division. By the 1840s, political leaders like Daniel O’Connell sought to distance Catholics from the implications of the failures of 1798. Catholic involvement in 1798 was, therefore, only an example of ‘second-hand sedition’ and the rebellion itself ‘had solely defensive and protective aims, into which Catholics had been unwillingly driven by brutal repression.’ [24] The 1803 insurrection, once again led by Protestants, such as Russell and Emmet, demonstrated exactly the same point.

Conclusion

In conclusion, it is difficult to over-estimate the vast implications of the 1798 Rebellion on the young Robert Emmet. The overarching feeling of bitterness and resentment can be found throughout the 1803 Proclamation. However, this mood was influenced not only by Emmet’s close relationship with the veteran’s of 1798, but his subsequent decision to restructure the organisation of United Irishmen, and his changing opinion of Irish self-identification as a result of his experiences in exile in France.

Emmet, like most 1798 leaders, a member of the Protestant Ascendancy, continued on with his doomed rebellion as a result of his particular understanding of national independence, which were centred on the sacrifice of the individual for une nation and evolved out of Emmet’s close ties with 1798 and the dark shadow which the ghosts of ’98 cast upon him.

Emmet himself, summarises the need to break away from the religious and political shackles of 1798, in his direct address to the Irish people and the British government, ‘Of the efficacy of a system of terror . . . you have already had experience . . . We will not imitate you in cruelty.’[25]

In the end we must ask, just why did Emmet continue with the rebellion, even though he knew it was doomed to failure? In the days leading up to the rebellion it seemed as if everything that could go wrong did. It began with the explosion at the St. Patricks ammunition depot on 16th July, alerting the authorities to their plans a week before the planned insurrection. On the very night of the rebellion only eighty of the planned 2,000 men actually turned up at the Thomas St. Depot, many of whom were drunk, having stopped at local taverns en route. Why then did Emmet fool hardily continue with this presumably suicidal mission?

Did he have a death-wish; was he obsessed with the need for a blood sacrifice, an idea cemented in the national conscious over a century later by Patrick Pearse. Or was it even the desire to go down in history as a great martyr for the cause? On the other hand, was it a more altruistic reasoning which compelled Emmet to go ahead with the rebellion? Perhaps he inherently understood the burden of leadership, a leadership which came with the ethical dilemma of an inevitable death, yet knowing the importance of his act of defiance.

Many similarities can be found with the rebellions led by the United Irishmen in 1798 and 1803. They both contained an elite group of members of the Protestant Ascendency at their core, French aid had been promised to both and failed to materialise. However the crucial difference between the rebellion of 1798 and that of 1803 was the Act of Union.

Whereas the rebels of 1798 were rising against an ostensibly Irish government in College Green, Emmet’s insurrection was directed against a British administration in the newly formed United Kingdom. Emmet rebellion was thus a straightforward fight for Ireland’s freedom and independence, more so than even the veterans of ’98 could claim Emmet continued on with his doomed rebellion as a result of this new impetus for Irish independence. This particular understanding of national independence, which had become become the basis of his political and ideological beliefs, was centred on the sacrifice of the individual for une nation and evolved out of Emmet’s close ties with 1798 and the dark shadow which the ghosts of ’98 cast upon him.

Bibliography

Primary

Emmet, Robert. ‘The 1803 Proclamation of the Provisional Government’, in Patrick Geoghegan Robert Emmet, A Life. Dublin 2002. pp. 287-294.

Secondary

Bartlett, Thomas. The Rise and Fall of the Irish Nation, Dublin: 1992.

Bartlett, Thomas, ‘Britishness, Irishness and the Act of Union,’ in Dáire Keogh and Kevin Whelan (eds.) Acts of Union, The Causes, Contexts and Consequence of the Act of Union. Dublin: 2001. pp. 243-261.

Elliott, Marianne. Robert Emmet: The Making of a Legend. London: 2004.

Keogh, Dáire, ‘Catholic Responses to the Act of Union,’ in Dáire Keogh and Kevin Whelan (eds.) Acts of Union, The Causes, Contexts and Consequence of the Act of Union. Dublin: 2001. pp. 159-170.

Kleinman, Sylvie. ‘Social and linguistic perspectives on Robert Emmet’s mission to France’, in Dolan et al (eds.), Reinterpreting Emmet, Dublin: 2007. pp. 56-76.

Geoghegan, Patrick. Robert Emmet, A Life. Dublin 2002.

O’Donnell, Ruán. Robert Emmet and the Rising of 1803. Dublin: 2003.

Quinn, James. ‘Revelation and Romanticism’, in Dolan et al (eds.), Reinterpreting Emmet, Dublin: 2007. pp. 26-38.

Whelan, Kevin. The Tree of Liberty. Cork: 1996.

References

[1] Robert Emmet, ‘The 1803 Proclamation of the Provisional Government, in Patrick Geoghegan, Robert Emmet, Dublin, 2002. p. 288.

[2] Ibid.

[3] Ibid., pp. 72-3.

[4] Thomas Bartlett, ‘Britishness, Irishness and the Act of Union,’ in Dáire Keogh and Kevin Whelan (eds.) Acts of Union, The Causes, Contexts and Consequence of the Act of Union. Dublin: 2001, p. 256.

[5] Emmet, ‘The 1803 Proclamation.’ p. 288.

[6] Emmet, pp. 288-9.

[7] Emmet, p. 288.

[8] Geoghegan. p. 145.

[9] Emmet, p. 289.

[10] Emmet., p. 289.

[11] Geoghegan, p. 142.

[12] Geoghegan, pp. 104-5. Emmet, p. 290.

[13] Emmet, p. 293.

[14] James Quinn, ‘Revelation and Romanticism’, in Dolan et al (eds.), Reinterpreting Emmet, Dublin: 2007, p. 27

[15] Whelan, The Tree of Liberty, p. 155.

[16] Emmet, p. 289.

[17] Thomas Bartlett, The Rise and Fall of the Irish Nation, Dublin: 1992, p. 240.

[18] Emmet, p. 289.

[19] Quinne, p. 26.

[20] Emmet, p. 290.

[21] Whelan, p. 135.

[22] Dáire Keogh, Catholic Responses to the Act of Union,’ in Dáire Keogh and Kevin Whelan (eds.) Acts of Union, The Causes, Contexts and Consequence of the Act of Union. Dublin: 2001, p, 161.

[23] Emmet, p. 291.

[24] Whelan, p 151.

[25] Emmet, p. 293.