Violence against women in Belfast, 1920-22 – part 1: Killing and lethal violence

By Kieran Glennon

Between July 1920 and October 1922, at least 499 people lost their lives in the city of Belfast due to political violence in the period known to nationalist memory as the ‘Belfast Pogrom’. Of these, seventy five were women or girls.

In recent years, increasing attention has been paid to the issue of violence committed against women during the course of the Irish revolution. Marie Coleman says this took a range of forms: “The violence against women in Ireland during the years 1919 to 1921 can be categorised as physical, psychological, gendered and sexual.”[1]

This article argues that in Belfast between 1920-22, women and girls faced two arcs of violence: one political/sectarian, one gender-based; while the former was often lethal and the latter was non-lethal, at times they intersected.

The first part, below, will deal with lethal violence against women.

Physical violence: women and girls killed during the Belfast pogrom

Ciara Breathnach and Eunan O’Halpin have examined the death of a Tipperary woman named Kate Maher in 1920; they state that:

“Between 1917 and 1921, there were 98 female deaths (4 per cent) within the 2346 recorded as linked to political violence. The great majority were clearly unintended, the women and girls involved dying either in traffic accidents with official vehicles (15 per cent), killed as bystanders during engagements between Crown forces and the IRA, or casualties of indiscriminate firing during intercommunal violence in Belfast city (where 27 per cent of all female fatalities arose).”[2]

They also say that “Only a handful of those deaths were the result of the deliberate targeting of females.”[3] This echoes a comment by O’Halpin in his introduction to The Dead of the Irish Revolution: “In general, females were not regarded as legitimate targets for any of the contending forces.”[4]

The circumstances in which the first woman was killed during the Belfast pogrom support their statement.

Killings of women in Belfast in 1920 tended to be the unintended consequences of rioting and shooting in urbans areas, but this changed as the violence grew more bitter.

At about midnight on 21st July 1920, Margaret Noade left her home in the Short Strand to visit her dying mother who lived across the river in the Market area. Crossing the Albert Bridge, she found the Market convulsed in rioting which had been going on since teatime – in response to the expulsions of Catholics and so-called “rotten Prods” from their workplaces in the city’s shipyards earlier that day, local residents had attacked trams bringing Protestant shipyard workers home.

By the time Noade arrived in East Bridge Street the street lights had been smashed. Attempting to evade the violence, she was shot and killed by a Royal Irish Constabulary (RIC) Sergeant, Henry Slacke. At the inquest into her death, Slacke stated that he had fired to scatter the rioters and claimed that while chasing them, he had stumbled and fired the fatal shot inadvertently.[5]

However, the incident in which the last woman was killed in Belfast in this period was far removed from “indiscriminate firing.” On the morning of 5th October 1922, Mary Sherlock had just left a butcher’s shop on the Newtownards Road when someone walked up behind her and shot her in the head at point-blank range.[6]

Between those two dates, seventy-five women and girls were killed in Belfast. In many respects, these killings followed the wider patterns of fatal violence in the city in this period.

In terms of chronology, only a minority of twenty occurred prior to the watershed month of November 1921, after which the Unionist government of Northern Ireland assumed direct control of policing and security and the violence intensified.

As regards location, twenty-two, or almost a third, took place in the York Street-North Queen Street area, which saw the highest overall number of killings of any part of Belfast.

As was the case with politically-related killings generally, a disproportionate number of the females killed were from a nationalist background – fifty-four or 72% of the seventy-five; in the 1911 Census, Catholics accounted for only 24% of the city’s population.

Sixteen of the females killed were teenagers and eight were aged 12 or younger, so almost a third of them were not yet adults. The oldest was Rose McGreevy, aged 83; the youngest was Isabella Foster, aged just 6 months.

The nature of the killings

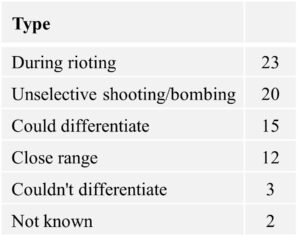

The incidents in which these women and girls were killed can be grouped into five types: those in which they were victims of generalised firing during rioting, unselective attacks on groups of opponents rather than individuals, attacks in which snipers could discriminate between male and female targets but chose not to, attacks in which they could not discriminate as easily, and killings that happened at close range.

Twenty-three, or almost a third, of the killings happened during rioting – these correspond to the description offered by Breathnach and O’Halpin. Many can be attributed to firing by the RIC or British military in order to quell disturbances, but that is not to say that those killed were necessarily engaged in rioting.

Some simply fell victim to stray shots or ricochets, as was the case with Mary Ann Weston: on the evening of 23rd July 1920, she was standing at the corner of Welland Street and the Newtownards Road, talking to her sister, when she was hit by a bullet – roughly half a mile away, soldiers near St Matthew’s church had fired a volley to disperse rioters.[7]

Some were not even outside on the street when killed. Maggie Savage, aged 18, was sitting in the front room of her parents’ house in Burke Street in the New Lodge area while rioting was in progress nearby on 26th March 1922: a bullet came through the window, killing her instantly.[8]

In the remaining fifty-two killings of females, the motive was political/sectarian – the women and girls were killed primarily on account of their membership of either the nationalist or unionist community; their gender was almost irrelevant.

The second-largest group of killings consists of incidents in which twenty women or girls were killed as a result of sectarian violence directed at members of one or other community – these can be termed unselective as the targets were not individually chosen.

The most notorious such case was an attack which took place in Weaver Street in north Belfast on 13th February 1922 when a bomb was thrown at a group of children playing on the street – four girls aged between 11 and 15, as well as two adult women, were killed.[9]

This was not the only attack like this – Elizabeth McCabe was killed on 23rd April 1922 when a bomb was thrown at churchgoers entering St Matthew’s on the Newtownards Road; Louisa Cannon was killed on 14th September 1922 when a bomb was thrown at a number of women and teenagers standing chatting on Cullingtree Road in the Lower Falls.[10]

By 1922 women were being targeted deliberately, simply for being members of the ‘enemy’ community.

Not all such unselective killings involved bombs. On 14th June 1921, Kathleen Collins, aged 18, was shot dead in Cupar Street off the Falls Road as members of the Ulster Special Constabulary (USC, or “Specials”), returning from the funeral in the City Cemetery of a colleague who had been killed, began firing wildly. Mary McGowan, aged 13, was machine-gunned from a police Lancia armoured car in the Lower Falls on 11th July 1921 as the RIC and Specials mounted a generalised attack on the area in the aftermath of the Raglan Street ambush, in which a policeman had been killed.[11]

The third group of killings was those in which the killers could differentiate between male and female targets, but chose not to.

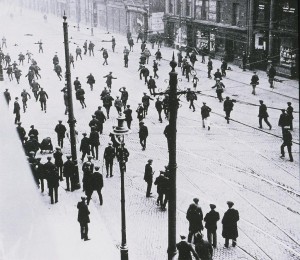

As the image to the right shows, in the 1920s, women and men had distinctively different clothing, with women typically wearing long, often ankle-length dresses, while men wore trousers. This meant that women and men could easily be told apart, especially while on the street in daylight hours. In the case of girls, a further distinguishing feature was the common wearing of pinafores, a lighter-coloured apron worn over a dress.

Such clear identification of females proved to be no deterrent in fifteen cases. At 10am on 23rd November 1921, 70-year-old Ellen Bell was shot dead by a sniper in Great Patrick Street, off York Street, as she went to visit her son; at the inquest into her death, there was no reference to any rioting or other disturbance in the area at the time.

Nellie McMullan was killed by a sniper in Great Georges Street just before teatime on 16th May 1922 as she made her way home from her place of work, Gallagher’s Tobacco in nearby York Street.[12]

Shortly after 5pm on 20th May 1922, Bridget Skillen’s mother gave her a penny to go and buy herself a bun; it is inconceivable that she would have done so if there had been rioting going on in the area. Apart from her distinctive clothing, Bridget’s small stature would have told the sniper who killed her that she was not an enemy combatant – she was 3 years old.[13]

Three women were killed by snipers at night-time, when it might not have been as possible to differentiate between women and men.

In the remaining group of twelve killings, the killers would have been in no doubt that they were shooting women, as the victims were shot at very close range, often by intruders into their homes or shops. On 30th May 1922, the bodies of Mary Ann McIlroy and her daughter Rose were found at the rear of their home on the Old Lodge Road – they had vainly attempted to escape their killers by fleeing to their tiny back yard.[14]

Mary Hogg was perhaps the most overtly-targeted woman of the seventy-five to be killed: on the evening of 11th January 1922, some men called to her house in Fifth Street in the Shankill and asked for her by name – when she came to the door, they shot her in the head and chest.[15]

While it is likely that many hundreds of women and girls survived efforts to kill them, it is worth mentioning one failed attempted killing that took place in June 1922, as it was horrific even by the standards of Belfast violence of the time and had no parallel with any other incident elsewhere in Ireland. The intended victim, Susan McCormick, made a statutory declaration to a Commissioner of Oaths in Belfast, in which she gave a first-hand account of what had been done to her:

“‘I remember the night of June 1, 1922, between 9 and 10, when a man came to the door of Doctor McSorley’s surgery, and rang the bell. I opened the door, and the man at it asked if Doctor McSorley was in and I replied that he was out on a sick call. While speaking to him, two other men came forward and said that they would wait inside until the Doctor returned. I said that it would be better for them to call back again. They then forced their way in and said they would wait. They then immediately pushed me back, and I fell. They must have thrown something in my eyes, as my eyesight failed me. When on the ground they kicked me about the head, face, body and legs. When I had been thoroughly beaten and kicked, they then threw petrol on me and struck a match and lighted, it, and at the same time lighted the hall lamp. When I was ablaze I managed to get a hold of the handle of the door, otherwise I would have been burned to death. When I got to the door the men decamped, and the neighbours came to my assistance.’”[16]

Over the course of the pogrom, the killings evolved between the different types. Historian Tim Wilson has noted,

“… the Great War had militarised the business of crowd control. Rioting was now routinely suppressed using automatic weaponry … Such tactics help explain why the massive set-piece rioting of July and August 1920 was not repeated. Street disturbances did not disappear in Belfast, but they do seem to have become smaller.”[17]

The majority of the female fatalities during rioting occurred prior to November 1921 – sixteen of the twenty-three women and girls killed in this way throughout the pogrom; conversely, only four of the twenty female fatalities in the period July 1920 to October 1921 did not happen during rioting.

But from November 1921 onwards, targeted killings became the norm. All but two of the unselective shootings and bombings aimed at either community happened after that point. Similarly, all but two of the incidents in which snipers killed identifiably female victims came after the same month – eight of them in May 1922 alone. All the point-blank killings of women (and one teenage girl) were carried out from December 1921 onwards.

But from November 1921 onwards, targeted killings became the norm. All but two of the unselective shootings and bombings aimed at either community happened after that point. Similarly, all but two of the incidents in which snipers killed identifiably female victims came after the same month – eight of them in May 1922 alone. All the point-blank killings of women (and one teenage girl) were carried out from December 1921 onwards.

In general, up to November 1921, female fatalities occurred on the peripheries of larger-scale communal clashes. But from then on, as the sectarian violence became increasingly unsparing, and woman and girls were directly targeted, whether in groups or individually, as members of the ‘enemy’ community.

Women’s role in the violence

As far back as the period before the Easter Rising, the Belfast branch of Cumann na mBan had provided rifle training to its members – at Christmas 1915, it organised a shooting competition with the local battalion of the Irish Volunteers: the women took the first and second prizes.[18]

While there is no documented evidence of women participating in the pogrom fighting as combatants, neither were they simply docile victims of the other side’s violence.

Cumman na mBan were heavily involved in republican armed activities in Belfast, as to a less documented degree were women attached to loyalist groups

The women of Cumann na mBan played a vital supporting role to the Belfast IRA in transferring weapons from arms dumps to the locations of incidents and returning them afterwards. So, for example, Elizabeth McClean gave evidence to the Military Service Pensions Board in 1941 concerning her activity:

“During this period your house was used as a dump for arms. Some arms were kept in a dump in the ceiling and these included four rifles and 2 or 3 Thompson machine-guns. There were also some margarine butts containing small arms and ammunition. There was another dump under the floorboards in the bed-room, which was mainly used for keeping ammunition. There were as many as 9 rifles kept also at times in your wardrobe in the front room …

On 7 or 8 occasions, when Vol[unteer]s were going on jobs, you took up to 2 or 3 revolvers to them to appointed places. You also took revolvers back again from them and brought them back to the dump …

About April, 1921, you shifted a basket of revolvers and ammunition from Alton Street to the dump at your house. Your sister helped you in this work.

With your sister you also helped shift a dump of 9 rifles from Marchioness Street to your own place …

Now would that be a fair statement of your activities before the Truce?

Yes. I think that is very fair.”[19]

The members of Cumann na mBan were not the only women engaged in such activities. In May 1922, a Royal Ulster Constabulary (RUC) report noted that:

“At 10 p.m., two girls named Agnes Forsythe, (P[rotestant]) 71 Joseph Street, and Minnie Patterson, (P) 37 Foreman Street, were arrested in Alfred Street, having in their possession a U.V.F. rifle, by Const. Fitzpatrick, College Square. They were conveying the gun from Sandy Row to Shankhill [sic] Road.”[20]

Relatively little has been written about non-state loyalist paramilitaries during the Belfast pogrom; further research would be required to establish whether there were counterparts to Cumann na mBan on the loyalist side or if the pre-war UVF women’s auxiliary was revived.

Psychological violence against women in Belfast

The second form of violence against women listed by Coleman is psychological violence. Trying to estimate the impact of this on Belfast women in this period – and afterwards – highlights the many potential sources of trauma for them.

While 75 women and girls were killed, so were 424 men and boys – they left behind grieving widows, mothers, daughters and sisters.

As well as men, women were expelled from their jobs, thus depriving them of economic agency. Brendan O’Leary quotes an estimate that 1,000 women were victims of workplace expulsions in the summer of 1920.[21]

Women and children made up the bulk of Belfast refugees from the city in the spring and summer of 1922.

Families were driven from their homes – women were particularly affected by this emotionally because in the 1920s, the domestic space was still very much seen as their domain. No one has yet completed a comprehensive tally of the number of families burned out of their homes during rioting – it was definitely measured in the hundreds, most likely over a thousand and possibly as many as two thousand. Fear of suffering the same fate and in many cases, receipt of threatening letters, prompted thousands more to “flit” from their homes before they were burned out – Robert Lynch references 8,000 Catholics and 2,000 Protestants who were forced to move within Belfast.[22]

Even more fled Belfast altogether, some to Scotland but the majority of them to Dublin – Lynch quotes three different estimates ranging from 10,000 to 30,000 leading him to conclude that “in many senses, the Belfast Catholics were Ireland’s partition refugees.”[23]

The emotional impact of bereavement, violent loss of employment and being forced to flee one’s home can at least be estimated. What can only be imagined is the constant mental strain of living for over two years with the dread that rioting or shooting might break out in the neighbouring streets, that hostile mobs might invade the area where you lived or that troops, police or Specials might arrive at any time to search and ransack your home.

The full psychological violence suffered by Belfast women was beyond measure.

Part 2 of this article will examine the extent to which Belfast women suffered gendered and sexual violence in this period.

If you enjoy the Irish Story and wish to support our work, please considering contributing at our Patreon page here.

References

[1] Marie Coleman, Violence against Women during the Irish War of Independence, 1919-21 in Diarmaid Ferriter & Susannah Riordan (eds) Years of Turbulence – the Irish Revolution and Its Aftermath (University College Dublin Press, Dublin, 2015), p139.

[2] Ciara Breathnach & Eunan O’Halpin, Sexual assault and fatal violence against women during the Irish War of Independence, 1919–1921: Kate Maher’s murder in context, Medical Humanities 2022;48:94-103.

[3] Ibid.

[4] Eunan O’Halpin & Daithí Ó Corráin, The Dead of the Irish Revolution (Yale University Press, London, 2020), p13.

[5] Belfast News-Letter, 3rd August 1920.

[6] Northern Whig, 7th October 1922.

[7] Belfast News-Letter, 11th August 1920.

[8] Belfast Telegraph, 27th March 1922.

[9] Belfast News-Letter, 4th March 1922.

[10] Belfast News-Letter, 1st June 1922; Belfast Telegraph, 23rd September 1922.

[11] Northern Whig, 29th June 1921; Belfast Telegraph, 11th August 1921.

[12] Belfast News-Letter, 12th January 1922; Northern Whig, 20th June 1922.

[13] Irish Weekly & Ulster Examiner, 24th June 1922.

[14] Northern Whig, 19th July 1922.

[15] Belfast News-Letter, 25th January 1922.

[16] Statutory declaration by Susan McCormick, 9th May 1922, in Statutory declarations by Belfast Catholics re atrocities perpetrated by members of Ulster Special Constabulary, National Library of Ireland (NLI), Ms 33,010.

[17] Tim Wilson, The Belfast Troubles at One Hundred in Caoimhe Nic Dháibhéid, Marie Coleman & Paul Bew (eds), Northern Ireland 1921–2021: Centenary Historical Perspectives (Ulster Historical Foundation, Newtownards, 2022), p32.

[18] Ann Matthews, Renegades – Ireland’s Revolutionary Women 1900-1922 (Mercier Press, Cork, 2010), p113.

[19] Elizabeth McClean, Pensions & Awards files, Military Service Pensions Collection (MSPC), Military Archives, MSP34REF27554.

[20] Occurrences in Belfast 24/5/1922, in File of reports by R.I.C. on incidents in Belfast, April-May 1922, Public Record Office of Northern Ireland (PRONI), HA/5/151A. Both Joseph Street and Foreman Street were in the unionist Shankill area in west Belfast.

[21] Brendan O’Leary, A Treatise on Northern Ireland, Volume 2: Control (Oxford University Press, Oxford, 2019), p22.

[22] Robert Lynch, The Partition of Ireland 1918-1925 (Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 2019), p171.

[23] Ibid, p175-176.