Violence against Women in Belfast, 1920-22 – Part 2

Kieran Glennon

Part 1 of this article examined the first two of the forms of violence against women in the revolutionary period outlined by Marie Coleman: “The violence against women in Ireland during the years 1919 to 1921 can be categorised as physical, psychological, gendered and sexual.”[1]

This part investigates the extent to which Belfast women were subjected to gendered (or gender specific) and sexual violence.

Gender-based and sexual violence during the Irish revolution

In terms of defining gender-based violence, Gemma Clark says it “can be physical, emotional, psychological, and sexual (the latter encompassing rape, but also any sexual act performed without an individual’s consent).”[2]

Linda Connolly has offered a more detailed list of the types of violence inflicted on women during these years, including:

“(1) ‘sexual harassment’ … and rough searching; (2) hair cutting, cropping, shearing, pulling or ‘bobbing’; (3) hair-cutting assaults combined with other physical injury/assault/harassment; (4) physical attack and injury (such as a beating or assault with a rifle/implement/fist/belts); (5) assault and sexual attack involving rape and gang rape; (6) and murder or kidnapping combined with some or even all of the above.”[3]

A distinction can be made between violence such as forcible hair-cutting which is based on the victim’s gender but does not include sexual contact, and various degrees of sexual assault up to and including rape. However, it is important to note that, as Clark points out, sexuality also lay at the core of hair-cutting attacks:

“While it does not involve sexual contact, forced hair cutting nonetheless targets a part of the body ‘historically … associated with eroticism and sexuality’ … its removal thus marks out physically women who have transgressed social and sexual norms (by collaboration with the enemy, for example) – and symbolically defeminises the target.”[4]

The distinction between forcible hair-cutting and sexual violence lies in the fact that in this period, only the former was used as a prescribed, deliberate tactic against women.

Its use as a tactic was initiated by the IRA. In November 1919, the unionist Belfast News-Letter scoffed that “considerable amusement” met an announcement by IRA headquarters in Dublin which it went on to quote:

“‘It has been deemed proper, both for the safeguard of morality [emphasis added by author] and as a stoppage of bad example, to publish the names of culprits, also to warn them after certain dates after the publication of this proclamation those who persist in the above-mentioned scandalous and at the same time unpatriotic company-keeping, are liable to the punishment of being branded by having their hair cut off.’”[5]

IRA units around the country soon began enforcing the directive. According to Susan Byrne: “It was a tool to control women who were considered deviant and its execution was billed as a punishment. The woman was constructed not as a ‘victim’ but as a ‘perpetrator’, and her punishment was therefore deemed justified, both to the attacker and to the wider community.”[6]

Initially, forcible hair-cutting was an IRA tactic to penalise women who fraternised with the enemy. But it was later also adopted as a weapon by crown forces, though they were not following a similar explicit instruction from above in doing so:

“Hair shearing might be placed within a larger spectrum of unofficial reprisals against civilian populations, which also includes arson, deployed by British forces (‘Black and Tans’, Auxiliaries) in order to control the population and rout republican influence, during the War of Independence.”[7]

So, both sides attacked women in this way – as Mary McAuliffe has noted: “The crown forces, fighting a war it [sic] could not win, took its frustrations out on a civilian population, and from late 1920, on women suspected of aiding the enemy. The IRA, fighting for the cause of freedom, used gendered violence as a way of disciplining ‘its’ women.”[8]

The IRA often forcibly cut the hair of women as punishment for ‘keeping company’ with Crown forces in 1919-21, who retaliated in kind against republican women.

However, various historians have stated that, in contrast to other later conflicts elsewhere, sexual violence was not deployed as a deliberate tactic during the Irish revolution – for example, Louise Ryan says that “unlike colonial wars in other regions, British forces did not use rape as a weapon of war” while Clark says “G.B.V. [gender-based violence] was not used in a systematic way to realise political/military objectives.”[9]

Commentators have also pointed out that the various combatant organisations actually had strong reasons to discourage sexual attacks being committed by their forces. All parties to the conflicts would have been aware that such attacks on Belgian women by invading German soldiers in 1914 contributed to the characterisation of the “rape of Belgium” and would have been anxious to avoid similar negative publicity for themselves.

So, in relation to the War of Independence, Ryan says “Hence for both sides the treatment of women became an indicator of chivalry and courage or evil and cowardice.”[10] Accordingly, in July 1921, at the County Down Assizes in Downpatrick, a serving British soldier was convicted of indecent assault.[11] But Ryan also notes that “the need to publicize the brutality of the adversary sometimes outweighed the need to protect female reticence and innocence.”[12] As regards the Civil War, Clark states that “it did not serve the strategy or ideology of either warring side … to denigrate women en masse.”[13]

Coleman offers an additional argument – that the sense of comradeship between women and men arising from the close involvement of Cumann na mBan in the republican struggle may have militated against the IRA using sexual violence: “The significant role played by women in the Irish independence campaign is therefore a possible explanation for why male republican fighters did not resort to one of the most objectionable forms of violence against women.”[14]

Quantifying the extent of the various forms of violence against women is difficult.

Sexual violence was not used as a systematic terror tactic in the Irish Revolution, but levels of sexual assault do seem to have been higher than in peacetime.

In relation to forcible hair-cutting, Byrne carried out a survey of four newspapers: the Irish Times, being pro-unionist and pro-government, might be expected to eagerly highlight republican wrong-doing, while the Irish Independent was a nationalist paper with nationwide coverage and the Cork Examiner and Kerry People were both based in Munster, where the general violence was most intense.

She found that “between January 1919 and December 1923, thirty-two attacks were covered, with twenty-seven of these occurring in 1920. It was reported that fifty women had their heads shorn, with six ‘haircuts’ attributable to Black and Tans/Auxiliaries/British army, while thirty-one can be attributed to the IRA/Volunteers/Nationalists.”[15]

It should be pointed out that this was a very limited sample – as will be explained, if Belfast newspapers had also been included, she would have found a considerably larger number of attacks. In that respect, it almost certainly under-estimates the real number of hair-cutting attacks. Speaking at a recent conference, McAuliffe referenced her ongoing research in which she has so far found 254 hair-cropping incidents across Ireland in 1919-23.[16]

When it comes to the prevalence of sexual violence, the problem of measurement becomes almost overwhelming.

Due to the social inhibitions and sensibilities relating to sexuality in general, both reporting and prosecution of such crimes were extremely rare. Surveying British records for Ireland, Breathnach and O’Halpin note that:

“No judicial statistics were returned for 1920 or 1921. But even in normal times, the record of criminal investigations of sexual assault cases was abysmal. In 1919, the last year for which civil administrative records are available under British administration, only one case involving a sexual assault was recorded in the Irish judicial statistics, and there were no prosecutions. No instances of defilement of girls under 16 or 13 were reported, although two cases dating from earlier years saw the perpetrators receive some months’ imprisonment. Only one other sexual offence was reported, that of incest, and there were no rape prosecutions. Five cases of indecent assault were successfully prosecuted, with sentences ranging from 2 to 6 months.”[17]

However, against this not just low but almost non-existent bar, Connolly has identified nine cases of military rape and sexual assault in the Civil War period alone – one in Armagh and eight in the south.[18]

In addition, Ryan points to the contemporary Irish Bulletin, which highlighted a further case of rape and another of sexual assault, both carried out against named women by crown forces in 1921. While the Bulletin might be dismissed as an instrument of republican propaganda, Síohbra Aiken has pointed out that the original testimonies of the victims, one a handwritten sworn affidavit, remain in existence.[19]

Whether or not these cases qualify as “widespread” can be debated but they do represent an increase against peacetime levels.

It seems clear that hair-cutting attacks were more numerous than those involving sexual violence. Nevertheless, there were incidences of the latter. While it was officially frowned on by all combatant organisations, some of their members did act opportunistically to transgress against social behavioural norms and perpetrate such attacks against women. The conflicts provided the backdrop against which those attacks were made but unlike forcible hair-cutting, attacks involving sexual violence were not an integral tactic of those conflicts. As such, the motivation for them must be found elsewhere – a point which will be addressed below.

Sexual violence in Belfast

Did women in Belfast experience similar attacks from 1920-22?

Two Belfast men were prosecuted for indecent assault during this period – one pleaded guilty to common assault instead and received a suspended sentence, the other was convicted and sentenced to three months’ prison.[20]

On three occasions, nationalist women in the city were subjected to sexual assaults by Specials. The most serious of these was outlined in an affidavit sworn by Isaac Catney, husband of one of the women:

“On Monday the 3rd April 1922 I was in my own house 5 Joy Street Belfast having my tea. About 6.30 pm Mrs Carthy who lives next door to me, came in to see me and said there was a man with a Webley revolver, who was holding up her husband James. I then went into Mrs Carthy’s, and going up stairs I met a man coming down stairs with a Webley revolver, who ordered me down stairs and used filthy language. I then went back to my house and told Mrs Carthy it was a Special who was holding up her husband James. This Special got drunk and was arrested. On this occasion he attempted to rape my wife and another woman.”[21]

That was not the end of this particular incident. That night, according to Catney, a man accompanied by another Special came to investigate the conduct of the drunken Special. Ten days later, the house was broken into by Specials, windows and doors smashed, and shots fired. On the second occasion, Isabella Catney feared a repetition of her previous encounter with a Special:

“I ran into the adjoining flat for safety, and was followed by four of the men … The leader put his arms around me, and said ‘I know you, I met you a fortnight ago’ and he asked me where my husband was, and I replied that I did not know.”[22]

At the same time the Specials were raiding the Catneys’ flat, they were also raiding other flats in the same building which housed refugees from Ballymacarrett. Three members of the local IRA fired to repel the raid, then at a Lancia armoured car which arrived with police reinforcements, leading to the fatal wounding of Special Constable Nathaniel McCoo; three other Specials were also wounded. It was probably no coincidence that the Catneys swore their affidavits the very next day after this gun battle.[23]

There are three recorded cases of sexual assault by Ulster Special Constables against nationalist women in Belfast in 1920-22

Isaac Catney’s statement was later paraphrased by the Dáil Éireann Publicity Department in one of its press releases; in an illustration of how sensibilities around sexuality could override the impulse to reap the maximum propaganda benefit, the final line quoted above was amended to “He attempted to outrage my wife and another woman.”[24]

Euphemism was similarly deployed in May in a way that obscures the precise nature of the incident – it was stated that Specials tried to “criminally assault two young girls” in Park Street in the Carrick Hill area.[25]

However, the investigators for the Dáil Publicity Department were more explicit when they reported that on 25th May:

“Two uniformed Specials held up two boys and a girl, a sister of one of the boys, going for morning papers on Falls Road at 6a.m. The girl was called a filthy name and was told to hand over the ammunition she was carrying. She was forced against the wall and one of the Specials attempted to open her blouse. She screamed and some youths came to her rescue. The Specials fired at them and the fire was returned by the youths killing one of the Specials and wounding the other who escaped.”[26]

On this occasion, Special Constable James Murphy was killed, almost certainly by the IRA.[27]

But the Specials were not the only perpetrators of gender-based violence in Belfast.

Hair-cutting attacks in Belfast

There were fifteen incidents of hair-cutting during the 1920-22 conflict in Belfast – in three of them, an element can be seen to link them to the wider political/sectarian violence that gripped the city and in each of those three, it was nationalists who committed the attacks.

The first was in March 1921: Lily Stitt came home from shopping on the Newtownards Road to find two men in her kitchen, who asked for her brother, a Special; on replying that he wasn’t home, they cut off her hair. She fainted and they ransacked the house – they found a number of Orange sashes and regalia and a Union Jack which they burnt, muttering “This will not float any longer.” Before leaving they said they would “get Jimmy yet,” a reference to her brother.[28]

In the second, in October 1921, the sectarian aspect is implied when the micro-geography of the particular area is taken into account. Sarah Wilson, a Protestant woman was taking a shortcut through the nationalist Clonard area to her home in the Shankill – a number of men surrounded her, warned her that “You are going this road too often” and cut off her hair.[29]

There were fifteen incidents of hair-cutting in Belfast 1920-22 – most occurred in robberies but three had sectarian overtones.

The final hair-cutting incident linked to sectarianism was recorded in an RUC report of May 1922: two men entered the house of Mary Sherman, a Protestant woman living in the majority-nationalist Sailortown area and cut off her hair. According to the police, “The object of the outrage appears to have been to drive Mrs Sherman out of the locality.”[30]

While it is impossible to generalise on the basis of three incidents, they do share one thing in common: in contrast to hair-cutting attacks in the south, where the IRA punished women in its own community, these three Belfast attacks involved nationalist intimidation of women from the opposing community. In that respect, they more closely resemble similar attacks by crown forces in the south.

The newspaper report on one woman who was attacked in March 1921 is too scant to allow a precise motive to be determined: “The victim in this instance was Mary Robinson, who was accosted by two men on her way home to her residence, 182, Spamount Street. Her assailants, after having tied her hands behind her back, cut off her hair, and she was then allowed proceed home.”[31]

However, the majority of the fifteen hair-cutting incidents took place in the course of robberies and do not appear to be directly connected to the political strife in Belfast at that time.

The very first such attack to be reported was perpetrated on a woman named Tillie Best in the city centre in January 1921 – so it pre-dated the first of the sectarian hair-cutting attacks. Two men entered the office where she worked and demanded the week’s takings. She tried to flee to a storeroom but was caught and fainted; when she came to, “her tresses had been shorn” and the thieves had made off with only her handbag.[32]

Women had their hair cut during the course of three more robberies the following month: Charlotte Cunningham on 11th February in her family home off the Oldpark Road in north Belfast; Carrie Briggs on 26th February in the shop where she worked on the Lisburn Road in south Belfast; Violet Morrison on the same date at her home on Summer Street in the Oldpark area.[33]

Two more similar incidents followed in the next month: on 9th March, “… at the corner of North Howard Street [Shankill area], when a girl named Lucinda Irvine, who lives in Sixth Street, was attacked, robbed of between thirteen and fourteen shillings, and had her hair cut by the thieves.” Then on 14th March, a Mrs Lindores of Midland Street, also in the Shankill, opened her front door to a man who “asked for alms, and when she gave him a copper he was displeased, and assaulted her. She screamed for help, fainted, and collapsed, and when her husband arrived on the scene from next door, where he had been paying a visit, it was found that her hair had been cut on one side.”[34]

On 3rd April, a woman named Blanche Hamill was attacked by three men, robbed of her purse and had her hair cut in an incident in a lane off Rosetta Park, which at the time was in the very southernmost suburb of Belfast at the end of the Ormeau Road.[35]

After that, there were no more hair-cutting assaults on women reported until the following December, when Rebecca Stevenson in Ballymacarrett in the east of the city gave £2 to two armed robbers who broke into her home “but not content with robbery they seized her and cut off her hair close to the head.” The following month, a domestic servant, Georgina Smart, was robbed and had her hair cut by two men who broke into her employer’s home on the Antrim Road in north Belfast while he was at church.[36]

The final incident occurred in June 1922 in Dundonald, now a suburb but then a village to the east of Belfast; once again, two armed men demanded money, the unnamed woman initially refused but when they cut off her hair and threatened further injury, she gave them £12.[37]

Only two of these hair-cutting attacks had consequences of any kind. In March 1921, a man from the Lower Falls was convicted of assault and larceny for his part in the attack on Carrie Briggs the month before. In 1922, Blanche Hamill claimed £1,000 damages for the attack on her in Rosetta Park the previous year: “His Honour said he regarded the assault on the girl as a very serious matter. To have cut her hair was a very great indignity. Fortunately the girl had not sustained any permanent injury, though her nerves had undoubtedly been affected. He gave a decree for £50.”[38]

Apart from the fact that all of these attacks were made on women, the only common denominator is that they involved robbery. The number of perpetrators varied from one to three and they happened in all parts of the city, north, south, east and west, making it unlikely that the same men were involved each time.

In some cases, the robbers cut the woman’s hair to force her to reveal where money was to be found but in others, they cut her hair regardless, having already robbed her. The latter type of assault would suggest that there was an element of misogynistic trophy-taking overlaid on top of the robbery motive.

There was one hair-taking incident in Belfast where misogyny could not have been a factor because the victim was a male teenager: Alphonsus Moore, a York Street butcher’s assistant had his hair cut off by a lone attacker while at work, for no apparent reason; there was no robbery involved.[39]

However, it should be stressed that this hair-taking attack on a male was unique among such incidents in Belfast and it should be treated as an outlier.[40]

The robbery-related hair-cutting attacks are puzzling and problematic.

In any of the literature on gender-based violence during the revolutionary period, there are no references to similar attacks happening during non-political robberies in the south of Ireland.[41]

But such attacks were not unique to Belfast. Hair-taking attacks on women, some involving robbery, some not, were also reported in Britain in locations as far apart as Motherwell in Scotland and London, so this kind of assault was clearly not an exclusively Irish phenomenon.[42]

Were the Belfast robberies copy-cat attacks? Only a few days before the first hair-cutting attack, that on Tillie Best in January 1921, the Northern Whig had carried a report on a similar robbery at Ilford, near London, during which the thieves had cut the hair of a servant to force her to reveal where household valuables were kept.[43]

Further research on robberies which involved hair-cutting, not just in the south of Ireland but also in Britain, might throw some light on these questions.

Summary and conclusions

This article has attempted to use the forms of violence against women listed by Coleman in the introduction as a framework for examining the violence suffered by women in Belfast during 1920-22.

This article has attempted to use the forms of violence against women listed by Coleman in the introduction as a framework for examining the violence suffered by women in Belfast during 1920-22.

As previously outlined, the full extent of the psychological violence defies measurement. But based on the kinds of violence that can be measured – physical, gendered and sexual – it can be said that women and girls in Belfast faced two arcs of violence in this period. These were not of equal scale but they did intersect.

The first flowed from the political/sectarian conflict which swept the city in those years. In Belfast, this arc of general violence was directed at females to a far greater degree than was the case with political violence in the rest of Ireland. In the period up to December 1921, females represented 4% of the national fatalities according to The Dead of the Irish Revolution.[44] In Belfast across 1920-22, the female proportion was almost four times’ higher, at 15%; among nationalists, it was higher again, at 19%. As political violence in Belfast was primarily directed at non-combatants, women and girls in the city were far more likely to be killed than their counterparts in other parts of the country.

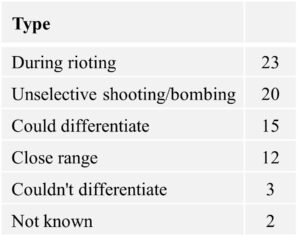

The types of incidents in which seventy-five females were killed in Belfast changed considerably over the course of the conflcit.

In general, prior to November 1921 they were mainly killed incidentally, as bystanders or the unintended consequences of military and police firing to break up rioting mobs. As The Dead of the Irish Revolution only surveys the period to the end of December 1921, Breathnach and O’Halpin’s assertion that “Only a handful of those deaths were the result of the deliberate targeting of females” is accurate in relation to Belfast for that particular timeframe.

This research has shown that only four killings of women or girls in the city in that period resulted from intentional attacks. There may have been taboos against killing women and children, but up to late 1921, they were largely not put to the test – although those four killings would suggest that any such taboos were fragile. However, after November 1921, they were shattered.

From then on, women and girls were mainly killed because their enemies actively wanted to kill someone, anyone – or preferably, a number of people – from that community: there was now both intent and a sectarian motive. These killings took a number of forms, most notably: unselective bombings or shootings directed at groups of women and girls or at houses where “the other side” lived, sniper attacks where the killers could differentiate between female and male targets but paid no notice to their targets’ gender and close-range killings, mainly in women’s homes or workplaces.

So, when the entire period of the pogrom is considered, it was very much the case that females were treated by both sides as legitimate targets.

The second, non-lethal, arc of violence had its root in the attitude that women were inferior to men and that men were entitled to treat them as such.

This discriminatory view underpinned the denial of the right to vote for all women in the UK until 1918; the franchise was extended to some women at that point, but those aged between 21-30 remained excluded until 1928 and those aged 18-21 until 1970. The same attitude was also at the heart of misogynistic behaviour towards women, extending to the various degrees of sexual violence.

In Belfast between 1920-22, that misogyny was expressed in the sexual assault of Catholic women by Specials but was also expressed in non-political settings such as the robberies, accompanied by hair-cutting, that took place. Some of the hair-cutting attacks were coercive – seeking to induce or punish particular kinds of behaviour – while some involved male triumphalism, where the woman’s submission to coercion was irrelevant as her hair would be treated as a trophy in any event.

In terms of how the two arcs of violence intersected, Clark has a useful formulation in which she talks of “Violence against women in wartime – as [being] distinct, though not divorced, from violence in domestic and/or social settings.”[45]

Bearing this in mind, the forcible cutting of Protestant women’s hair by nationalists can be seen as being a direct element – although not a common one – of the sectarian conflict, while the cutting of robbery victims’ hair and the Specials’ sexual assaults were opportunistic transgressive attacks that the men responsible perpetrated and felt they could get away with amid the chaos of the wider political violence. In a city awash with guns, armed robbery was rife, while the other men would not have been Specials but for the pogrom; in that sense, the pogrom created the opportunities and provided the backdrop against which these attacks happened.

The second arc – gender-based and sexual violence – also intersected with pogrom-related violence in a wider sense in that two Specials were killed by the IRA as a result, not because they were attacking women but because they were attacking Catholics. The attempted rape of Isabella Catney was the first in a chain of events in houses within a few doors of each other in Joy Street which culminated in the death of Special Constable McCoo, while the screams of the girl being sexually assaulted on the Falls Road drew the attention of an IRA patrol which then killed Special Constable Murphy.

These two arcs of violence that Belfast women faced in 1920-22 differed considerably both in magnitude and impact. Seventy-five women and girls were killed, compared to six that we know of who were subjected to sexual assaults and fifteen to hair-cutting attacks, and the fate of the seventy-five was objectively worse than that suffered by any of the victims of gender-based or sexual violence.

However, another critical difference between these arcs of violence was that one ended and one did not. The last pogrom-related killing was in October 1922 but long after that, misogyny continued to fuel sexual violence against women.

I would like to acknowledge the encouragement to write this article generously offered by both Ciara Breathnach and Margaret Ward.

If you enjoy the Irish Story and wish to support our work, please considering contributing at our Patreon page here.

References

[1] Marie Coleman, Violence against Women during the Irish War of Independence, 1919-21 in Diarmaid Ferriter & Susannah Riordan (eds) Years of Turbulence – the Irish Revolution and Its Aftermath (University College Dublin Press, Dublin, 2015), p139.

[2] Gemma Clark, Violence against women in the Irish Civil War, 1922–3: gender-based harm in global perspective, Irish Historical Studies (2020), 44 (165), p75–90.

[3] Linda Connolly, Towards a Further Understanding of the Sexual and Gender-based Violence Women Experienced in the Irish Revolution in Linda Connolly (ed) Women and the Irish Revolution: Feminism, Activism, Violence (Irish Academic Press, Newbridge, 2020), p106-107.

[4] Clark, Violence against women in the Irish Civil War, p86.

[5] Belfast News-Letter, 10th November 1919.

[6] Susan Byrne, ‘Keeping company with the enemy’: gender and sexual violence against women during the Irish War of Independence and Civil War, 1919–1923, Women’s History Review, Vol. 30, No.1 (2021), p108-125.

[7] Clark, Violence against women in the Irish Civil War, p87.

[8] Mary McAuliffe, The Homefront as Battlefront in Connolly (ed) Women and the Irish Revolution, p179-180.

[9] Louise Ryan, ‘Drunken Tans’: Representations of Sex and Violence in the Anglo-Irish War (1919-21), Feminist Review, No. 66, Political Currents (Autumn, 2000), p73-94; Clark, Violence against women in the Irish Civil War, p85.

[10] Ryan, ‘Drunken Tans’, p88.

[11] Northern Whig, 15th July 1921.

[12] Ryan, ‘Drunken Tans’, p90.

[13] Clark, Violence against women in the Irish Civil War, p78.

[14] Coleman, Violence against Women during the Irish War of Independence, p152.

[15] Byrne, ‘Keeping company with the enemy’, Appendix 1: Summary of hair-cutting attacks: 1919–1923, p124-125.

[16] Mary McAuliffe, Violence and indiscipline? The treatment of ‘die hard’ anti-treaty women by the National Army, 1922-1923, paper delivered at Irish Civil War National Conference, University College Cork, 17th June 2022.

[17] Ciara Breathnach & Eunan O’Halpin, Sexual assault and fatal violence against women during the Irish War of Independence, 1919–1921: Kate Maher’s murder in context, Medical Humanities 2022;48:94-103., p95.

[18] Connolly, Towards a Further Understanding, p106.

[19] Ryan, ‘Drunken Tans’, p89; Síobhra Aiken, Spiritual Wounds – Trauma, Testimony & the Irish Civil War (Irish Academic Press, Newbridge, 2022), p119.

[20] Northern Whig, 17th March 1921; Belfast News-Letter, 22nd August 1922. A third case, in which a man was acquitted of indecent assault, was only reported in the press on 21st July 1920, the day of the initial shipyard expulsions, so it clearly pre-dated the pogrom – for that reason, it is not included here; Belfast News-Letter, 21st July 1920.

[21] Statutory declaration by Isaac Catney 14th April 1922, in Statutory declarations by Belfast Catholics re atrocities perpetrated by members of Ulster Special Constabulary, National Library of Ireland (NLI), Ms 33,010. I am hugely grateful to Tim Wilson for sharing with me his research on these incidents involving Specials; normally, I follow other peoples’ footnotes the way that Hansel and Gretel followed the trail of breadcrumbs – here, Tim just gave me the whole gingerbread house.

[22] Statutory declaration by Isabella Catney 14th April 1922, in ibid.

[23] Statutory declarations by Maggie Boyle 14th April 1922, and Patrick Masterson 20th April 1922, in ibid; Henry Crofton, MSPC, Military Archives, MSP34REF00106. Crofton lived at 13 Joy Street, four doors away from the Catneys; apart from him, the other IRA members involved were Joseph McPeake and Joseph Doran. For a more extensive account of the raid on the refugees’ house, see Irish Weekly & Ulster Examiner, 22nd April 1922. McCoo died in early May – see Northern Whig 8th May 1922.

[24] Freeman’s Journal, 15th June 1922.

[25] Tim Wilson, Frontiers of Violence, Conflict and Identity in Ulster and Upper Silesia, 1918-1922 (Oxford University Press, Oxford, 2010), p77 n6.

[26] Statutory declarations by Belfast Catholics re atrocities perpetrated by members of Ulster Special Constabulary, NLI, Ms 33,010.

[27] Belfast Telegraph, 25th & 26th May 1922.

[28] Northern Whig, 4th March 1921.

[29] Northern Whig, 24th October 1921..

[30] Occurrences in Belfast 29/5/1922, in File of reports by R.I.C. on incidents in Belfast, April-May 1922, PRONI, HA/5/151A. Mary Sherman lived in Fleet Street in the predominantly nationalist Sailortown district off York Street, scene of the most intense violence in Belfast during this period.

[31] Belfast News-Letter, 16th March 1921. Spamount Street was in the then-mixed New Lodge area in north Belfast; the 1911 Census shows several women named Mary Robinson, of varying ages and religions, living in or near this area.

[32] Belfast Weekly Telegraph, 22nd January 1921.

[33] Belfast Telegraph, 12th February 1921; Northern Whig, 28th February 1921.

[34] Northern Whig, 11th March 1921; Belfast News-Letter, 16th March 1921.

[35] Northern Whig, 5th April 1921.

[36] Belfast News-Letter, 5th December 1921; Belfast News-Letter, 2nd January 1922.

[37] Irish Weekly & Ulster Examiner, 10th June 1922.

[38] Northern Whig, 23rd May 1922.

[39] Northern Whig, 13th October 1921.

[40] In May 1921, one of the Belfast newspapers reported an attack in Coagh, Tyrone on an 18-year-old male shop assistant: “His legs and arms were tied with ropes, and a label attached to his neck warned informers to beware, being signed by the I.R.A. The youth was badly beaten and his hair cut off.” Northern Whig, 2nd May 1921.

[41] Susan Byrne refers to a hair-cutting linked to a robbery in Derry in November 1920; Byrne, ‘Keeping company with the enemy’, Appendix 1: Summary of hair-cutting attacks: 1919–1923, p125.

[42] See, for example, Aberdeen Press & Journal, 11th September 1920; Leicester Evening Mail, 20th April 1921; Hartlepool & Northern Daily Mail, 23rd April 1921; Illustrated Police News, 28th April 1921.

[43] Northern Whig, 17th January 1921.

[44] O’Halpin & Ó Corráin, The Dead of the Irish Revolution, p12.

[45] Clark, Violence against women in the Irish Civil War, p77.