Today in Irish History, 22 June 1922 – The assassination of Henry Wilson

The killing of a British Field Marshal that helped to spark the Irish Civil War. By John Dorney

The killing of a British Field Marshal that helped to spark the Irish Civil War. By John Dorney

The assassination

On June 22, 1922, Field Marshal Sir Henry Wilson arrived back, by taxi, at his home on Eaton Square London. The 58 year old had been at the unveiling of a war memorial to the fallen of the Great War at Liverpool Street station.

Unknown to him he had been followed home by two Irish veterans of that war, Joe O’Sullivan and Reggie Dunne, the former had lost a leg at Ypres. Dunne and O’Sullivan were also, however, members of the Irish Republican Army and before Wilson had made it from the taxi to his front door, they gunned him down.

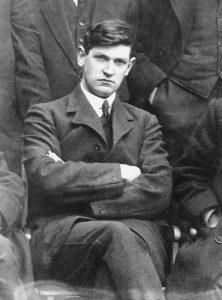

Henry Wilson, a British Field Marshall, was gunned down outside his home in London by two IRA men.

Two policemen were shot and wounded trying to stop the assassins’ getaway before they were set upon by a vengeful crowd. When more police arrived on the scene, possibly saving the two from a lynching, they were arrested and charged with murder. They were hanged in August of that year.[1]

Henry Wilson was the most senior British military or political figure to die during the Irish revolution and his death inadvertently triggered the outbreak of the Irish Civil War just six days later.

Who was Henry Wilson?

Henry Wilson was a hate figure for Irish Republicans.

He was at the time of his death in 1922, a field marshal of the British Army, the highest rank that one could attain in that force, in which he had served since 1881, though wars in Burma, South Africa and the Great War in 1914-18.

Born into a Protestant, landowning Irish family with extensive lands in county Longford, Wilson was both a convinced imperialist and an ardent Irish unionist. His father and brother had stood, unsuccessfully, in Longford constituencies as Unionist candidates in the 1880s and 90s and Henry Wilson, too, was stridently opposed to Home Rule for Ireland.

In 1914, when Ulster unionists organised in arms against Home Rule, Wilson, in his capacity as Major General, told his commander in Chief Sir John French that he would not fire on the unionists in support of Home Rule, nor would he deploy to Ulster to enforce it. Wilson’s truculence, along with the actions of other officers in the so-called Curragh mutiny, did much to derail the peaceful implementation of Irish self government and ultimately to radicalise Irish politics.

Wilson had served as Chief of the Imperial General Staff and was a staunch unionist.

Wilson served in the senior echelons of the British Army throughout the First World War, acting as liaison between the British and French forces, a pivotal role in attempting to coordinate the two allies. He served from 1918 as Chief of the Imperial General Staff.

He maintained his hardline stance on Irish affairs, favouring a policy of military suppression of the IRA and Sinn Fein, or as he put it, to ‘declare war on the Sinn Feins’; an attitude which led to him clashing on numerous occasion with Nevil Macready, commander in chief of the British military in Ireland, who maintained that the only solution to the problem was a political one.[2]

Wilson raged throughout the War of Independence against the government’s half measures in Ireland and disapproved of the deployment of paramilitary police in the Black Tans and Auxiliaries, whom he described as a group with ‘no discipline, no esprit de corps, no training, no cohesion’. He would have preferred instead to flood the country with up to 80 battalions of regular troops and to declare martial law [3].

When back channel talks looked like they might secure a ceasefire with the insurgent Irish Republicans in late December 1920, Wilson was ardently opposed. At a cabinet meeting which he attended in his military capacity on December 29, he voiced the opinion that it would be ‘absolutely fatal’ to agree to a ceasefire before the IRA was defeated and disarmed.[4]

He was also opposed to the truce of the 1921 which ended the War of Independence, insisting to the end that military victory was in sight. He told Prime Minister Lloyd George that, ‘we are having more success than usual in killing rebels and now is the time reinforce and not to parley’.[5] He described the Truce itself which came into effect on July 11, 1921, it as ‘rank filthy cowardice’ on the part of the British government.

Retiring as Chief of the general staff in January 1922, he became a military advisor to the new Northern Ireland government, where, at least he could vindicate his unionist goals in that part of the island. He was also elected as Unionist MP for North Down.

Wilson, the career soldier, disapproved of some of the actions of the Ulster Special Constabulary, which included the extrajudicial killing of many Catholic non-combatants in the spring and early summer of 1922. But with his hardline unionist views, Wilson largely took the blame in nationalist public opinion for the treatment of the Northern minority.

Michael Collins for one, now head of the Provisional Government in what was to become the Irish Free State, referred to him as a ‘violent Orange partisan’.[6]

A fraught context

The killing of Wilson was a decisive factor, as we shall see, in the outbreak of the Irish Civil War. As a result, who ordered the shooting and why remains a source of great controversy to this day.

It occurred at a particularly sensitive time, when the IRA had split into antagonistic factions over the Anglo-Irish Treaty.

The pro-Treaty faction organised in the Provisional Government, led by Michael Collins, was attempting to get the Irish Free State off the ground. Their political representatives had just secured a majority in the Free State’s first general election on June 16.

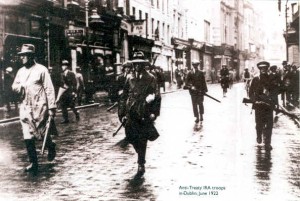

The Wilson assassination occurred at a time of great tension with the IRA having split into hostile factions over the Anglo Irish Treaty.

The anti-Treaty faction, and particularly an intransigent group in Dublin, which had taken over the Four Courts in the centre of the city, continued to flout the rule of the Provisional Government and their response to the June election had been to declare their intention to resume war against the British forces still in Ireland – either in Dublin or in the North – in order to collapse the Treaty.[7]

Meanwhile, to complicate matters even further, Collins, though his government was by this time supported and supplied by the British government, himself had recently cooperated clandestinely with the anti-Treatyites in a disastrous ‘Joint Northern Offensive’ against Northern Ireland in May and June 1922, in an effort to re-unite the Republican factions. This had even involved Collins handing over British arms to the anti-Treaty IRA faction.

Wilson was particularly reviled in Republican circles for his militarist views prior to the Truce and subsequently for his role as military advisor to the Northern Ireland government, at a time when hundreds of northern Catholics had been killed in the violence in Belfast.

Who ordered the killing?

There were thus reasonable suspicions on at least three groups for the killing of Henry Wilson; Michael Collins and pro-Treaty forces, the Four Courts garrison of the anti-Treaty IRA or possibly the London battalion of the IRA acting independently.

Ordering the killing would fit with Collins’ aggressive posture on the North from early 1922 onwards, and would be consistent with attempts to reconcile pro and anti-Treaty factions in Ireland with an action they would all approve of.

On the other hand, it does seem hard to believe that he would have risked hitting such a high profile target at such a delicate time, especially when he needed the backing of the British government.

Surprisingly, however, the circumstantial evidence for Collins’ involvement in the assassination is quite strong. Pro-Treaty military officer Joe Sweeney later told Ernie O’Malley that Collins was ‘very pleased’ when he heard of the killing, and that Collins had told him that he had ‘arranged it’. Similarly, Frank Thornton, one of Collins’ key intelligence officers was adamant that the shooting was carried out on the orders of [pro-Treaty IRA] ‘GHQ’.[8]

Several pro-Treaty figures went on record in saying that they believed Michael Collins had ordered the killing of Wilson.

Another pro-Treatyite, PS O’Hegarty thought that Collins had acceded to repeated requests by London IRA leader Sam Maguire to kill Wilson.[9] And Reggie Dunne, one of the assassins had met with both Collins and anti-Treaty leader Rory O’Connor in Dublin earlier in June 1922.[10]

Furthermore, whether he ordered the killing or not, Collins certainly looked into sending Squad and Dublin Active Service Unit (ASU) men on a rescue mission to free the gunmen before they were hanged.

According to Joe Dolan, by that time an officer in Irish Military Intelligence in Oriel House, Collins ordered him to go to London to meet Sam Maguire, and to look into a rescue effort. Dolan reported that snatching the prisoners on their way to court was feasible if he had six Squad or ASU men. But by the time he got back to Dublin the Four Courts had been attacked and the Civil War was on, putting paid to the plan.

Dolan stated; ‘There is nothing more I can say from my personal knowledge on this incident except to express my firm belief that Collins did instruct Dunne to carry out the execution of Wilson. The Belfast pogrom was still going on and we all knew that Wilson was one of the chief forces at the back of it’.[11]

Anti-Treaty IRA Intelligence in 1924, in the wake of the Army Mutiny claimed that Richard Mulcahy, secretly acknowledged that Collins’ men were behind the Wilson shooting.[12]

At the time, however, Collins’ cabinet colleagues, including Mulcahy were, reportedly ‘incensed’ by the assassination of Wilson of which they had known nothing.[13]

The British government blamed the anti-Treaty faction and put great pressure on Collins to attack their base in the Four Courts.

On the other side of the Treaty split, despite Reggie Dunne having previously met with Rory O’Connor, the Four Courts garrison leadership appear to have known nothing about the killing, though they did not disapprove.

Anti-Treaty political leader Eamon de Valera, somewhat evasively, said of the shooting, ‘Killing any human being is an awful act but the life of a humble worker or peasant is the same as the mighty. I do not know who shot Wilson or why, it looks as if it was British soldiers [the two gunmen were Great War veterans] but life has been made hell for the nationalist minority in Belfast especially for the last six months… I do not approve, but I must not pretend that I misunderstand’.[14]

George White an anti-Treaty Volunteer, also met with a London IRA commander, Kelleher, about the possibility of rescuing Dunne and Sullivan, and even anti-Treaty IRA Chief of Staff Liam Lynch was approached, who said he would do what he could. According to White, Kelleher also spoke with Collins in Portobello Barracks but was afterward put under arrest. It appears therefore as if the London IRA appealed to both pro and anti-Treaty IRA factions to attempt to rescue the men.[15]

However, if the evidence against the anti-Treatyites is thin and the evidence against Collins is not conclusive, the possibility remains that the London IRA acted on their own.

The Scotland Yard detectives who investigated the case thought that Dunne and O’Sullivan acted without wider sanction and later, in August 1922, the British Home Secretary would report to the government that ‘we have no evidence at all to connect them, so far as the murder is concerned, with any instructions from any organised body’.[16]

The fallout

Whatever the truth is, for the British government, who, not unnaturally, given that the Four Courts garrison were making loud noises about declaring war on them, assumed the anti-Treaty IRA were responsible, the assassination was the last straw.

On June 22nd the same day as the assassination of Wilson, a letter arrived in Dublin, addressed to Collins from the Prime Minister Lloyd George.

It read,

‘the assassins of Henry Wilson had documents clearly identifying them as individuals with the Irish Republican Army and they further reveal the existence of a deeper conspiracy against law and order in this country. We have information that the Irregular elements of the IRA are to resume attacks on upon lives and property of British subjects both in England and in Ulster…

The ambiguous position of the Irish Republican Army can no longer be tolerated by the British government. Still less can Rory O’Connor be permitted to remain with his followers and his arsenal in the heart of Dublin in possession of the Courts of Justice organising and sending out from this centre enterprises of murder in your jurisdiction, the six counties [Northern Ireland] and Great Britain.

The British government feels entitled to formally ask you to bring it to an end forthwith. We are prepared to place at your disposal the necessary pieces of artillery…or otherwise to assist you as may be arranged. Continued toleration of this rebellious defiance of the principles of the Treaty [is] incompatible with its faithful execution…Now that you are supported by the declared will of the Irish people in favour of the Treaty they [the British Government] have a right to the necessary action to be taken by our government without delay’. [17]

It was the decisive step toward the outbreak of civil war, which formally broke out six days later.

When the Provisional Government sent back a noncommittal reply, Winston Churchill and the British Government, at a meeting in London ordered their military Commander in Ireland Nevil Macready, to attack and take the Four Courts.

Macready initially agreed but when he returned to Dublin changed his mind and took no action, writing back to London that the Provisional Government should be given another chance to take the Four Courts. The order for British troops to move was rescinded at the last moment. [18]

It was National Army troops, after a series of further provocations by both sides in Dublin, that would open fire on the Four Courts on June 28, sparking off nine months of Civil War – probably the very opposite of what the assassins of Henry Wilson had been trying to achieve.

References

[1] For an account of the assassination see Michael Hopkinson, Green Against Green, the Irish Civil War, p112

[2] Charles Townshend, , The Republic, the Fight for Irish Independence, pp.150, 142

[3] Charles Townshend, The Republic, the Fight for Irish Independence, p.139

[4] Michael Hopkinson, The Irish War of Independence, p.184

[5] Dorothy Macardle, The Irish Republic, p.414

[6] Keith Jeffrey, Field Marshal Sir Henry Wilson, a Political Soldier, pp273, 279

[7] Sean MacBride notes on June 18 convention, cited in Anne Dolan, Cormac O’Malley, No Surrender Here, p26-27.

[8] Hopkinson, Green Against Green, p.112

[9] Anne Dolan, Will Murphy, Michael Collins the man and the revolution, Kindle version loc1592

[10] Hopkinson, Green Against Green, p.113

[11] Joe Dolan, BMH WS 900

[12] Accordong to the IRA’s report, he ‘gave complete details of every murder by them (including Sir Henry Wilson) and declared that his attempts to have them brought under control were the cause of the internal troubles Twomey papers P69/11 DI to CS 29/5/1924

[13] Hopkinson, Green Against Green, p.114

[14] De Valera Papers UCD P150/1588

[15] George White BMH WS 956

[16] Cited in Peter Hart, The IRA at War, p.201

[17] Lloyd George to Collins 22 June 1922, Mulcahy Papers UCD P7/B/244

[18]Hopkinson Green Against Green p116-117