The Dublin Brigade IRA 1917-1921

The evolution of the Irish Volunteers in Dublin during the Irish War of Independence. By John Dorney.

After the Easter Rising of 1916, the Irish Volunteer movement in Dublin looked dead and buried, but by 1921 the Volunteers, now renamed the Irish Republican Army or IRA, had built a new formidable urban guerrilla organisation to fight the British presence in the Irish capital.

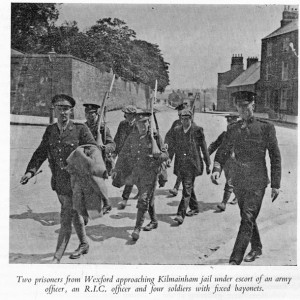

Up to 90 Volunteers of the Dublin Brigade and Citizen Army men lost their lives as a result the 1916 Rising and a further 1,000 were interned [1] , leaving only a shadow organisation left in Dublin. This might have been the end of the Volunteers in Dublin, had the British policy of repression been pushed through to its logical conclusion – the Volunteers interned serving out their long sentences of penal servitude. The organisation also lost most of its weapons.

The Dublin Brigade might have been finished after the failure of the Easter Rising, but British leniency allowed them to regroup in 1917.

But in fact the British response swung erratically from harshness to lenience. Most of the rank and file Volunteers were released in December 1916 and even the surviving leadership of 1916 were released in mid 1917.

Not all of the Rising veterans remained active after their release, but the Dublin Brigade was rebuilt in 1917 and 1918. The Dublin Brigade, like most Volunteer units around the country, received an influx of thousands of new recruits as it prepared to resist conscription, which the British government extended to Ireland in April 1918. Dublin Volunteers helped to marshal a General strike against conscription in April 1918 and were also involved in activities such as seizing food set to be exported to Britain and distributing it among the Dublin poor.[2] [3]

In the general election of December 1918, the Dublin Volunteers campaigned for Sinn Fein, stewarded their rallies and on occasion rioted with the families of those whose relatives were in the British Army. Sinn Fein won the election, not only in Dublin in all of Ireland and declared Irish independence and the formation of its own Parliament, the Dail.

On January 19, 1919, the Dail, met for the first time in Dublin’s Mansion House, and declared Irish Independence. Out of 75 TDs, 27 could not attend, however, being imprisoned.

On the same day in Tipperary Volunteers shot dead, in shootings unauthorised by the Volunteer command, two RIC constables were shot dead at Soloheadbeg in County Tipperary. Together the events, though unconnected, signalled the beginning of a new insurrection against British rule in Ireland.

Dublin Volunteers such as Todd Andrews Rathfarnham Company of the Dublin Brigade 4th Battalion, like all IRA Volunteers around the country, took an Oath of Allegiance to Dail Eireann and the Republic in the autumn of 1919, in his case in Ballyboden library.[4] The oath administered by GHQ went, ‘I will support and defend the Irish Republic and the Government of Ireland, which is Dail Eireann, against all enemies, foreign and domestic’.[5] From this point onwards they began to refer to themselves by a new name, the Irish Republican Army or IRA.

The Squad

Guerrilla war did not come immediately to Dublin however. Though 1919 saw some shootings in the city, it was not until mid 1920 that something akin to a war situation developed in Dublin.

The resumption of political violence began with Michael Collins’ formation of a shooting ‘Squad’ – fulltime paid operatives – in his Intelligence Department to eliminate Detectives of the Dublin Metropolitan Police. This was initially a reactive measure –a response to mass arrests of Sinn Fein activists in 1918-19.

The Squad according to one of its founder members, James Slattery, was formed on the 30th of July 1919 at a meeting on North Great George’s Street.

Dick McKee, the head of the Dublin Brigade, asked selected men, mostly from the north inner city second battalion if they had objections to shooting enemy agents. Many did. Their notion of warfare was akin to the ‘stand up fight’ of 1916, not clandestine assassination. But at least 6 men at the initial meeting did accept the task of premeditated targeted killing.[6]

The Squad the IRA Intelligence assassination unit was not formally part of the Dublin Brigade.

The Squad had an anomalous place within the IRA, being part of no recognised unit, independent even of the Dublin Brigade and answerable only to Collins himself as Director of Intelligence. In the Military Pension files it is described as the ‘GHQ Active Service Unit’.

The Squad started out with about 6 men and later grew to 12 men, hence the popular nickname, ‘The Twelve Apostles’ and had no more than 21 members by the time of the Truce in July 1921. The Intelligence Department had according to one founding member, Frank Thornton, only 6 men in 1919, though this also expanded considerably during the armed conflict.[7]. The numbers serving in Inteligence are hard to pin down exactly but together the Squad and Intelligence Department seem to have numbered about 50 men by the Truce.[8]

The Intelligence Department assembled information on targets, and according to Bernard Byrne, ‘came along to point out targets’. James Slattery recalled that orders for ‘jobs’ were given by Intelligence officers Liam Tobin and Tom Cullen and occasionally from Collins himself[9]. In practice though, the two units tended to bleed into each other. Squad men occasionally found targets for themselves.

On one occasion for instance, Tom Keogh and Bernard Byrne happened across a British Intelligence officer, Captain Cecil, ‘by chance’, followed him back to his hotel room on Wicklow Street and shot him beside his wife.[10] Conversely Intelligence men often went on ‘jobs’ themselves, not only pointing out the target but frequently pulling the trigger too.[11].

Over them all was ‘the Big Fella’, Michael Collins. Although Collins in theory held the rank only of Director of Intelligence in the IRA, everyone knew that in practice, he was the boss. His authority was based not on his official rank but on his personal charisma and this was true especially over his authority over the Intelligence Department and the Squad.

An Army inquiry in 1924 asked Charles Russell, a First World War veteran, junior IRA officer as of 1921 and later National Army Colonel, about Collins special position. Was Collins, the Inquiry asked, subject to Richard Mulcahy the IRA Chief of Staff? ‘No’, Russell replied, ‘he was Director of Intelligence, Commander in Chief and “the man”…. He was everything, he was General Collins, anyone knows that’. ‘He was chief man regardless of his position as D.I.’.[12]

The Intelligence Department and Squad were Collins’ men alone, according to Charles Russell; ‘if certain things that were carried out were done through ordinary Army channels they might not be carried out so well… they [Collins’ men] were if you like, the shock troops’.[13]

The Squad who were directly responsible to Michael Collins, carried out at least 25 assassinations in Dublin.

After a ‘job’ or a ‘plugging’ as the Squad came to call killings, they would report to Collins personally at Kirwan’s Bar or as Frank Thornton remembered, Devlin’s Pub on Parnell Street.[14] By the Truce of July 1921 they had killed at least 25 people. Collins’ targeting was selective but startlingly ruthless.

A list later compiled by Todd Andrews of those ‘executed’ on the orders of IRA Intelligence in Dublin lists 10 civilians killed by the Squad, including 6 in June 1921 alone, along with one ‘unknown man’, 13 DMP and RIC detectives, two ‘agents’ and one British Army officer. The civilians were mostly alleged informers but some like Allan Bell was a Magistrate investigating the ‘Dail Loan’ and Frank Brooke was a railway magnate advising the British Army on moving troops by train.[15]

Andrews’ figure of 25 dead at IRA Intelligence’s hands in Dublin is certainly an underestimate of the Squad’s tally, as he did not include the most spectacular assassination attack. This occurred in the early morning of November 21st, 1920 – later christened Bloody Sunday – when the Squad and Intelligence officers, along with several dozen gunmen from the Dublin Brigade were sent to over 20 addresses in central Dublin to kill British Intelligence officers and their informants – from a list compiled by Collins and the Intelligence Department.

Some of the targets were not in, others escaped but by daybreak 14 people had been shot dead; eight of them were British officers, of whom six were confirmed Intelligence agents, two Auxiliaries, the rest either bystanders or civilian informers [16]. They were killed mostly in their beds. In retaliation the Crown forces – RIC and Auxiliary police took the lead – opened fire on Gaelic football match at Croke Park, killing another 14 civilians. Three Republicans including Dick McKee, commander of the Dublin Brigade were also arrested and killed by Auxiliaries that night in Dublin Castle.[17]

The up close killing that the Intelligence Department and the Squad were asked to carry out and the constant stress of their battle of wits against British Intelligence took its toll on them. According to Charles Russell, ‘these men carried out the most objectionable work side of pre-Truce [War of Independence] operations’ which ‘left them anything but normal’. ‘If shell shock existed in the IRA prior to the Truce, the place to look for it was among these men’.[18]

Liam Tobin, the head of the Intelligence Department ‘looked like a man who had seen the inside of hell’.[19] Mick McDonnell, the original commander of the Squad was sent to California to recuperate in January 1921, ‘for health reasons’, though it is not clear if these were physical or psychological.[20] He was replaced first by James Slattery and then Paddy O’Daly.

It is hardly surprising, given that he was surrounded by a ruthless assassination unit, responsible to him alone, that Michael Collins’s position created tension with other leaders of the movement. So, to a lesser extent, did the authority of the IRA Chief of Staff Richard Mulcahy, who directed much of the IRA guerrilla campaign.

Both men had a difficult relationship with Cathal Brugha the Dail’s Minister for Defence. Brugha was unhappy with what he perceived as Collins’ personal authority –far beyond his official role of Director of Intelligence – over the IRA.

In fact on a number of occasions Brugha flexed his muscles and intervened to veto or modify a number of IRA operations in Dublin. Most notably on Bloody Sunday itself, Brugha reduced Collins ‘hit list’ from over 50 names down to 35 on the grounds that there was not enough evidence against some of those marker for death.[21]

The Dublin Brigade

The Dublin Brigade of the IRA was divided into four main battalions, 1 and 2 north of the river Liffey (First Battalion to the west of O’Connell Street and Second to the East), 3 and 4 south of it (Third Battalion in the inner city and Fourth in the more suburban area to the west and south). These formations tallied so closely with the Dublin Metropolitan Police Divisions, that it seems almost certain they were originally based on them[23]. Fifth Battalion was engineers and Sixth Battalion covered south county Dublin and neighbouring Wicklow.

The commander of the Dublin Brigade was Dick McKee, who was killed by Auxiliaries in Dublin Castle in revenge for the mass killing of British agents on Bloody Sunday in November 1920. He was replaced by Oscar Traynor, a veteran of the1916 Rising and Vice Commandant of Second Battalion.

The numbers in the Dublin Brigade fluctuated from about 2,000 in 1916 to a much larger number of temporary recruits in the conscription crisis of 1918, down to about 2,100 Volunteers in 1920-1921, though the active total was much smaller[24]. Generally speaking the rank and file Volunteers in Dublin came from a specific social stratum – the Catholic skilled working class and lower middle class.

Social Profile of the Dublin Volunteers

Todd Andrews remarked that in his Company of 4th Battalion, ‘the men were men of no property. Except for what little furniture the few married men had accumulated … But they were all in regular employment even if their jobs were menial, very badly paid and insecure. None of them were destitute. They had a minimum of food, clothing and shelter.[25]

Andrews himself spent his early years in Dublin’s tenements but his father and mother both ran their own small businesses meaning that by the time he joined the Volunteers in 1917 his family lived a comfortable life in suburban Terenure.

Though about a third of Dublin city’s 320,000 inhabitants lived in the slums and made a meagre and erratic living from unskilled labour, they were under-represented in the IRA. A study of 507 Dublin Volunteers found that 46% of them were skilled workers while only 23% were unskilled, with shop and clerical workers making up most of the remainder.[26]

The average Dublin Volunteers was a skilled worker and the average Dublin IRA officer was clerical worker.

Apart from the greater tendency to the very poor to serve in the British Army (much more regular payers than the IRA), this can probably explained by the fact that Volunteers had to pay a subscription of 3d a week to the organisation to pay for weapons and other costs. Dublin’s lumpen proletariat by and large did not have this much disposable income.

It may not be a coincidence that the fulltime Volunteers of the IRA in Dublin, in the Squad, the Intelligence Department, the Active Service Unit (ASU) and the Republican Police (together only about 200 men), were paid at the rate of a skilled worker, at about £4 per week. This was more than twice the average labourers’ wage which was 16-18s for a 48 hour week. [27]

A little higher up in the IRA, those who attained the rank of officer were generally of the lower rungs of the middle class. A study of 86 Dublin IRA officers found the largest single class were shop or clerical workers.[28] Frank Henderson for instance, commander of the Second Battalion was a clerk. Joseph O’Connor of the Third (nicknamed ‘Holy Joe’) worked as a civil servant in Dublin Corporation, Frank Thornton the Intelligence Officer worked for the New Ireland insurance firm[29].

For this reason, part of the IRA psychological make up was a feeling that they represented the ‘common people’ of Ireland. Not the ‘Imperialist’ or ‘Castle Catholic’ upper class, nor the ‘rabble’ that joined the British Army.

Todd Andrews remarked that the average Dublin Volunteer was a ‘Christian Brothers’ boy. It was rare to meet any ‘Diocesan boys’ – from the elite Catholic fee-paying schools (though there were some) and he hardly ever met a Protestant in the IRA, though again there were a handful. Andrews noted that IRA prisoners –he himself was interned from early 1921 – ritually said the rosary together as act of defiance.[30]

Another interesting demographic feature of the Dublin IRA is how many of its Volunteers were university students – Kevin Barry, hanged in November 1920 was a medical student at the ‘National’ or Catholic University College Dublin (UCD), as was Frank Flood, an ASU man hanged in March 1921, as were IRA officers Ernie O’Malley, Todd Andrews and Andy Cooney. At a time when only a small proportion of the population typically made it to third level education, it seems certain that university students too were over-represented in the Dublin IRA.

Finally, a significant number of Dublin IRA Volunteers were not originally from Dublin at all. Many, including all the above named university students apart from Andrews and Flood, were originally from elsewhere – Barry was from Carlow, O’Malley was born in Mayo, Cooney was from Nenagh County Tipperary. Analysis of the IRA men killed in Dublin from 1916 to 1921 indicates that about 20-30% of Republican fighters in Dublin were not natives of the city, but like many of the city’s inhabitants, migrants from the rest of Ireland. [31]

Arms and ambushes

Richard Mulcahy the IRA Chief of Staff wrote to embattled rural guerrilla commanders in 1921 that ‘Dublin is by far the most important military area in Ireland… The grip of our forces in Dublin must be maintained at all costs… no victories in distant provincial areas have any value if Dublin is lost in as military sense’.[22]

There were never even nearly enough weapons to arm all the young men who belonged to the Dublin Brigade. The British Army thought that even after the Truce when the IRA’s armament had improved somewhat, only about 10% of the ‘rebels’ in Dublin had access to rifles, 25% to revolvers and 35% to ‘bombs’. Given that most rifles in Dublin were sent to rural areas in mid 1920 this was probably an overestimate of the Dublin Brigade’s armament[32]

Until after Bloody Sunday, most IRA actions in Dublin were arms raids – as was for instance the raid in North King Street in which two British soldiers were killed and for which Kevin Barry was hanged. But most arms raids did not involve overt violence. Todd Andrews’ Company raided the local Big House for arms. Joe O’Connor’s Third Battalion bought and stole hundreds of rifles out of Wellington Barracks along the Grand Canal with the complicity of the Barracks Quartermaster.[33]

Up to late 1920, most of the Brigade’s activities were arms raids. Thereafter they concentrated on hit and run ambushes.

It was not until late December 1920 that IRA GHQ really committed the Dublin Brigade, as opposed to the Squad and Intelligence Department, to the fight. What the young men in the companies were expected to do, especially from late 1920 on, was to meet weekly for ‘parades’, where they would collect arms from a ‘dump’ and to ‘patrol’ their company areas. If and when they encountered British forces they were to attack them and make a quick getaway.

A typical IRA party on a ‘job’ in Dublin in 1921 carried improvised grenades and handguns only. [34]

The close presence of so many British troops and paramilitary police meant that prolonged fire-fights in urban situations were suicide for the IRA and making a quick getaway (and mingling into civilian crowds) was more important than firepower.

After the ‘job’ the revolvers and grenades were again hidden in a dump. Rank and file IRA Volunteers, when not ‘on patrol’ did not routinely carry weapons on the streets.

‘Factories’ were set up particularly in urban areas to manufacture grenades. In Dublin one clandestine workshop was churning out up to 1,000 improvised grenades per week by late 1920.[35] These were not always the most reliable weapons however. Often they did not explode and sometimes they exploded in the hands of the thrower.

The ‘patrol actions’ accounted for most IRA operations in Dublin. In the beginning, in early 1921 these were amateurish in the extreme. Todd Andrews recalled that in January 1921 his 4th Battalion Company had its first taste of action at Kenilworth Square; ‘We heard a lorry approaching from Terenure. We pulled our ‘dogs’ (we each had 45 Webley [revolvers]). It [the lorry] was packed with soldiers. They were all singing a popular song of the time ‘I’m forever blowing bubbles,’ We immediately opened fire, with Kane shouting, ‘we’ll give you f_ing bubbles’. The soldiers returned fire and the lorry accelerated just as [our men] threw their bombs at it’. Two soldiers were wounded.[36]

The IRA company ambushes evolved into something considerably more deadly in the coming months however. In March 1921 for instance, three British soldiers were killed and five wounded in a grenade attack on Wexford Street – a stretch leading from city centre to Portobello Barracks known as the ‘Dardanelles’ such was the frequency of ambushes on it.[37] The IRA in Dublin like all guerrillas, went through ‘combat evolution’, in other words, those who were reckless or careless were killed or captured. Those who remained learnt competence.

Mulcahy the Chief of Staff acknowledged the most active Battalions in Dublin were the Second and Third, ‘Most attacks are done by Battalions 2 and 3’, ‘1 and 4 are being worked up’. He advised in the spring of 1921, cutting transport, sniping and killing informers, or as he put it an ‘anti-tout offensive’. He also suggested that Volunteers rely on hand guns more than grenades in ambushes. [38]

The ASU

For more targeted attacks the Brigade set up an Active Service Unit (ASU) in December 1920. Like the Squad, these were fulltime, paid Volunteers. The aim was to recruit 100 men to the ASU but in fact there were closer to 50, divided into four sections along the lines of the Dublin Brigade Battalions. Unlike normal Volunteers they carried arms at all times.

One young recruit was Padraig O’Connor, a railway worker from county Kildare, a member of Fourth Battalion. Like the Squad, he recalled, they were given orders for ‘jobs’ by the Intelligence Department.

One of the ASU’s first operations ended in disaster however, when an attempted ambush in Drumcondra saw an entire section captured, six of whom were executed in March 1921. [39]

The Dublin Active Service Unit comprised about 50 men split into four sections. they were paid and carried arms at all times.

On the rare occasions where the IRA in Dublin were forced to stand and fight, their hand guns and ‘bombs’ were no match for British rifles and machine guns, especially when combined with armoured vehicles. One such occasion was the Great Brunswick (now Pearse) Street ambush in March 1921 when a patrol of Auxiliaries raided a Third Battalion base just as the Company patrol had returned. In five minutes of firing, seven people were killed, two men on both sides and three civilians. Two IRA men were captured, and another four wounded. Joe O’Connor remarked that it showed the dangers of Volunteers disobeying his explicit instructions to avoid prolonged engagements.[40]

An even worse setback was the IRA operation to burn the Custom House (centre of local government) in May 1921. Insisted on by Eamon de Valera, President of the Republic, the operation was a disaster especially for the Second Battalion. Out of over 120 Volunteers committed to the operation, none was armed with anything heavier than a pistol and improvised grenade – some had only a revolver and six rounds. When the building was surrounded by heavily armed Auxiliaries and British soldiers, five guerrillas were killed and 70-80 captured with only four Auxiliaries injured.[41]

Such were the numbers captured that the Squad and the Dublin ASU had to be amalgamated afterwards into a new formation – the Dublin Guards under Paddy O’Daly.

Though the IRA in Dublin was in general kept up under tighter control than units elsewhere and was therefore less free to pursue private vendettas, they certainly became more ruthless as the clandestine war went on. Only 2 civilians were killed as informers in Dublin until early 1921 but in the following six months over a dozen were shot in quick succession, mostly in May and June. At least 9 of these men were ex-servicemen and three were Protestants.[42]

By the summer of 1921 and the Truce of July 11, the British Army thought they were getting on top of the IRA in Dublin, but the guerrillas were far from finished in Dublin by that date.

By the end, with the British executing their fighters both officially and unofficially after capture, IRA units attacked British soldiers whenever they had the opportunity, whether they were on duty or not. A cricket game at Trinity College for instance was shot up in June 1921 because soldiers were playing; one woman spectator was killed. A mass assassination attack (a second ‘Bloody Sunday’) was planned on British Intelligence officers on the shopping thoroughfare Grafton Street in the summer of 1921 but never came off.

By the summer of 1921 and the Truce of July 11, the British Army thought they were getting on top of the IRA in the city; many had been arrested and interned. The guerrillas however were far from finished in Dublin by that date. There was no shortage of new recruits and the pace of attacks slackened only a little, even after the disaster of the Customs House attack. The Dublin Brigade recorded 67 attacks in the city in April 1921, 103 in May and 92 in June.[43] Ammunition was certainly a problem, in some cases IRA ‘factories’ in the city were put to work at the risky task of converting .303 rifle ammunition into .45 revolver bullets.[44]

However the IRA was also adapting. The first batches of Thompson submachine guns had arrived in the city and were used in several ambushes in Dublin in June 1921. There was also a turn towards avoiding combat altogether and destroying British war infrastructure. A raid on the Military transport depot in June 1921 destroyed 40 vehicles including five new British armoured cars, without any shooting taking place.[45] Whether the IRA was on the verge of collapse, particularly in Dublin or whether it was in a position to keep going later became a bitterly contested point.

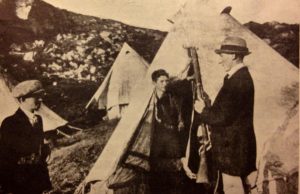

When the Truce with the British was agreed for July 11, 1921, the initial reaction among the IRA in Dublin was one of relief. Todd Andrews, who had been interned since January 1921 escaped from a military camp at Newbridge and made his way back to the city with the aid of sympathisers in Kildare. Back in south Dublin he found that he and his comrades were suddenly popular. The Squad and ASU men established a training camp in the remote Glenasmole valley in the Dublin Mountains.

A British Army report in October 1921 on the possibility of the resumption of hostilities reported that IRA, ‘in a desperate situation before the Truce’, with’ their ASUs an columns being chased and harried from pillar to post, defeated and broken up’, was now ‘a more formidable organisation’. They reported that the IRA was recruiting ex-soldiers to help with training was now better armed, including with the Thompson sub machine gun and also had far more rifles with which to carry out sniping attacks.[46]

Casualties

Some 300 people died violently in Dublin between January 1919 and July 11th 1921 and hundreds more had been wounded.[47]

The IRA counted 54 of their Volunteers killed in Dublin[48] and according to British figures, another 70 guerrillas at least were wounded in action and over 1,400 arrested and imprisoned.[49]

The British military admitted their losses in the city as 25 soldiers killed and 68 wounded, but a careful modern count found 35 killed by the IRA in the city with another 42 non-combat deaths due to firearms or other accidents, 3 murders of fellow soldiers and 12 suicides. [50]

Over 300 people were killed in Dublin in political violence between 1919 and July 1921. Due to the Truce there was no conclusive military result.

Some 40 policemen were killed in Dublin by IRA action, including 8 DMP officers, mostly detectives killed by the Squad, 11 Auxiliaries and 22 RIC or Black and Tans officers. In total, therefore about 75 Crown forces were killed in action in Dublin in 1919-21, a number that rises to about 110 once accidental deaths are included.[51] This would indicate around 150 civilian fatalities in the city, once combatants are subtracted from Eunan O’Halpin’s figures. [52]

Did the Dublin IRA win their war? Richard Mulcahy claimed that the Dublin IRA had, ‘pinned 1/6th of English armed forces [in Ireland] in the city without too much effort’.[53] The truth was though that in Dublin and elsewhere, the Irish War of Independence had no military conclusion. It was ended by a political compromise before a military decision was reached.

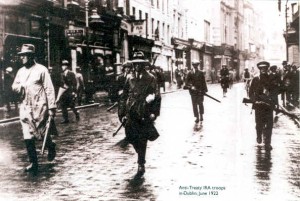

Disputes over the Anglo Irish Treaty, signed on December 6 1921 provoked a split in the Dublin Brigade and throughout the IRA. By and large, the Squad and the ASU in in Dublin sided with Michael Collins and the pro-Treaty side, while the majority of the Dublin Brigade’s battalions went anti-Treaty. It took a civil war between them before the Irish revolutionary period came to an end.

References

[1] 62 insurgents were killed in the fighting and between those who subsequently executed in the city (14) and those during or as a result of their imprisonment, (16 more either from wounds of sickness) the total of dead in the Dublin Brigade of the Volunteers rose to 90 (counting the Citizen Army men as Volunteers and also Thomas Ashe who died after force feeding on hunger strike in 1917)The Last Post pp 93-98

[2] Yeates City in Wartime pp 227, 234-236,

[3] Laurence Nugent WS 907

[4] Andrews, Dublin Made Me, p120

[5] IRA General Orders, Mulcahy Papers UCD P7/A/45

[6] James Slattery BMH Statement WS445

[7] Joe Leonard’s BMH statement says that by the end of the War of Independence the Squad was up to 21 members, Frank Thornton in his BMH Statement lists six men in the original Intelligence Department in 1919, though this later expanded considerably.

[8] The Military Pensions of 1924 list 17 men as having been Squad members at one time or another ten at least as members of Collins’ Intelligence Department, but these are understatements. Military Service Pensions Collection, online at Ton Ennis for example is named James Slattery as being a founder member of the Squad but this is not stated in his pension file.

[9] See James Slattery, Bernard Byrne BMH Statements

[10] Bernard Byrne BMH

[11] Ibid. James Slattery recalled that Intelligence officers Frank Thornton and Joe Dolan were given the job of killing an RIC Sergeant on Capel Street in October 1920 for instance, while Bernard Byrne recalled that Intelligence officer Frank Bolster was one of the gunmen who shot 2 RIC officers on Parliament Street in February 1921. Vinny Byrne lists Bolster, usually counted as an Intelligence officer, as a Squad member. Vincent Byrne BMH

[12] Charles Russell Testimony to Army Inquiry, 1924,Mulcahy Papers UCD P7/C/29

[13] Ibid. P/7/C/28

[14] Bernard Byrne BMH

[15] Andrews Papers UCD, P91/87

[16] Jane Leonard, ‘English Dogs or Poor Devils?’The Dead of Bloody Sunday Morning, in Terror in Ireland, p130

[17] See Michael Hopkinson, The Irish War of Independence, p 89-90,

[18] Russell Testimony to Army Inquiry, Mulcahy Ppaers UCD P/7/C/20

[19] Cited in Anne Dolan, ‘Ending War in a Sportsmanlike Manner’, in Thomas Hachey Ed. Turning Points in Twentieth Century Irish History., p35-36

[20] Michael McDonnell, Pension File

[21] T Ryle Dwyer the Squad, p190

[22] ‘War Overview, Richard Mulcahy to IRA Commanders, 4/3/1921, Mulcahy Papers UCD P7/A/47

[23] Eamon Broy in his BMH statement outlines the 6 DMP Divisions in Dublin. They correspond very closely with the IRA Battalions. Two north of the river Liffey, to south of it and G Division, the Detectives performing an analgous role to the Squad and IRA Intelligence.

[24]James Durney, ‘How Aungier/ Camden Street became known as the Dardanelles’, The Irish Sword, Summer 2010 No. 108 Vol. XXVII p245

[25] Andrews, Dublin Made Me, p113

[26] Hart, Peter, The IRA at War p119

[27] For labourers’ wages Yeates, a city in Wartime P48 For IRA wages, see Maire Comerford Papers UCD

[28] Hart, IRA at War, p119

[29] Frank Thornton BMH

[30] Andrews, Dublin Made Me, p134-135

[31]Out of the 80 Volunteers killed or executed in Dublin in the Rising of 1916, 27 were from outside the city (including 2 from Britain) and out of 54 IRA Volunteers killed in Dublin from 1919-21, 16 were from other parts of Ireland The Last Post p93-130

[32] Sheehan, Fighting for Dublin p126

[33] Andrews, Dublin Made Me, p121 Joseph O’Connor BMH

[34] Joost Augusteijn, From Public Defiance to Guerrilla Warfare, p165

[35] Joost Augusteijn, From Public Defiance to Guerrilla Warfare, p149

[36] Andrews, Dublin Made Me, p174-175

[37] James Durney, ‘How Aungier/ Camden Street became known as the Dardanelles’, The Irish Sword, Summer 2010 No. 108 Vol. XXVII p249

[38] Mulcahy Papers UCD P7/A/47

[39] O’Connor, Sleep Soldier Sleep, p33-34

[40] Great Brunswick St is no Pearse St. For the ambush see WH Kautt, Ambushes and Armour, The Irish Rebellion 1919-1921, p207-208, O’Connor BMH for his reaction.

[41] See Today in Irish History, the Raid on the Customs House.

[42] Joost Augusteijn counted 15 informers killed in Dublin, Padraig Og O Ruairc counts 13, of whom 9 were former soldiers or sailors, see Truce p101-102.

[43] Joost Augusteijn, Public Defiance to Guerrilla Warfare, p 173

[44] Maire Comerford Papers UCD LA/18

[45] Charles Townshend, The Republic, The Fight for Irish Independence, p290

[46] In Mulcahy Papers, P7A/48

[47] The figure is from Eunan O’Halpin’s ‘Counting Terror’ in Fitzpatrick Ed. ‘Terror in Ireland’ is 309 killed in Dublin. Though this may overestimate violence in Dublin a little as it includes those wounded elsewhere who died in hospital in the city. The death toll included at least 58 IRA members (per the Last Post), 25 British Army soldiers killed in action ( Per their report re-published in Wiliam Sheehan, Fighting for Dublin, p130 though more died there due to accidents, illness or suicide) and about 40 police, which would indicate well over 150 civilian fatalities in the city.

[48] See the Last Post

[49] Sheehan, Fighting for Dublin, p129-130

[50] Sheehan, Fighting for Dublin, p129-130 and the Cairo Gang website, here http://www.cairogang.com/soldiers-killed/list-1921.html

[51] Abbot, Police Casualties in Ireland It does not seem reasonable as some studies do, to include as conflict related casualties those soldiers, guerrillas or civilians who died of illness such as the ‘Spanish flu’ in 1918-19, which killed at least 2,600 people in Dublin alone. Padraig Yeates A City in Wartime p270-273

[52] Sheehan, Fighting for Dublin, p130

[53] Mulcahy Papers UCD, P7/A/47