Wellington Barracks, Dublin, 1922 – A Microcosm of the Irish Civil War

John Dorney looks at Wellington Barracks during the first 6 months of the Irish Civil War. We often concentrate on the emotional impact of this conflict, rather than its military aspect, but what was actually happening on the ground?

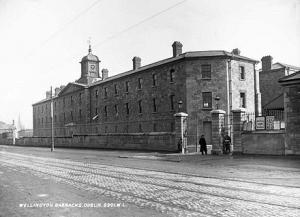

On April 12 1922, Wellington Barracks was one of the first British garrisons to be handed over to the new Irish Free State. [1]

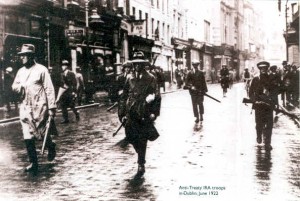

What would eventually become the Irish Army were still calling themselves, “Official IRA troops” – so recent was their transition from the guerrilla organisation. The other significance of the title “official” was to distinguish them from the “Irregular” IRA, the one that had rejected the Anglo-Irish Treaty and was opposing the establishment of the Free State.

At Wellington Jim Harpur, an officer in the National Army stationed at Beggars Bush, was told by Tom Ennis, “that Irregular elements were contemplating having the barracks handed over to them. He instructed me to get a company together and proceed to Wellington Barracks at 0800 hours. He undertook to inform the British O/C. ” The next morning when the Irish troops marched into the barracks, the British officer commanding duly presented arms, showed Harpur around the barracks and marched his men out with the band playing.

The Army issued a terse statement, “at 8 o’clock this morning, Wellington Barracks Dublin was taken over by Official IRA troops of the 2nd Eastern Division under Commandant T Ennis.” The Irish Times noted, “There was a complete absence of ceremonial and the formal handing over of the barracks [by the British Army] attracted little attention”.[2]

At that stage, despite tensions over the Treaty, the new garrison would have had no idea that, in their first year in the barracks, they would be charged with putting down a guerrilla campaign conducted against them by fellow Irishmen.

The Garrison

What was the composition of this garrison? It was, during the civil war, the centre of the Free State’s Eastern command under Dan Hogan, a former IRA commander from Monaghan. [3]

The garrison was mix of former IRA men, ex British soldiers and raw teenage recruits

It also housed the Army’s Intelligence Department under Charlie Dalton, brother of Emmet Dalton who was one of the National Army’s senior commanders. Both Daltons had been assassins for Michael Collins’ Squad in the struggle against the British. So had several members of his Intelligence unit in Wellington Barracks – such as Joe Dolan. [4]

During the Civil War, we can identify three separate functions of the garrison at Wellington. First, the Intelligence Department gathered information, launched raids on republican safe-houses and arrested and interrogated suspects. Their methods were sometimes brutal – of which more later. Most of the Intelligence Department’s officers were former IRA men.

Secondly, the troops were tasked with general patrolling in Dublin city, to guard against anti-Treaty IRA attacks and also to maintain civil order. Less than a kilometer away was Portobello (now Cathal Brugha) barracks, which housed another two battalions of National Army troops. They would have aided the Wellington Barracks garrison in patrolling. The strength of Wellington’s garrison in the November 1922 military census was listed as 612 officers and men.

Thirdly, Wellington Barracks was also a training depot where new recruits were knocked into shape before being sent to areas of guerrilla activity elsewhere in the country. Most of the NCOs who were in charge of this training seem to have been veterans of the British Army and of the First World War. [5]

The vast bulk of recruits, however were veterans neither of the British Army nor the IRA. Many were only boys of 16 or 17, recruited for a job, regular wages, meals and a place to live. The overwhelming majority of them were from Dublin’s working class inner city. Extreme youth, as we will see, was a characteristic of both sides in the civil war.

First attacks

Months before the official start of the Civil War, things were far from peaceful

Even in April, with the official start of civil war still months away, things were far from peaceful. Within days of taking over the barracks, the garrison at Griffith was attacked twice by Anti-Treaty IRA fighters. The Army statement said, “men dressed in civilian clothes came up to the gate and fired point blank at the men in the square” .Two men were wounded. The attackers sped away by car, only to be stopped at a roadblock and arrested. They were carrying two automatic pistols.

Only two days later, another, more determined attack was made. It was 11:20 and the troops were under curfew. Only the sentries at the gates of the barracks were still up, Suddenly fire opened from the rooftops all around the barracks. The sentries scrambled for cover behind a steam roller and bullets pinged off the granite bricks. For an hour, the two sides exchanged fire. Two attackers tried to rush the front gate, throwing grenades at the soldiers inside. They replied with bombs of their own. A total of five men were wounded in the skirmish.[6]

The incident happened during a rash of unclaimed attacks that coincided with Anti-Treaty forces’ occupation of the Four Courts.

Civil War

In late June, the undeclared civil war became official. Tom Ennis, the Commandant of Wellington Barracks, was in command of the Free State Government Troops who took the Anti-Treaty Republican’s position in Dublin. Within a month, the original garrison was sent to different parts of the country to break up anti-treaty resistance. By land and sea to Wexford, Cork, Kerry and elsewhere.

The original garrison of Wellington was sent by land and sea to Wexford Cork and Kerry, soon their bodies were coming back for burials

Soon soldiers’ bodies were coming back to the Barracks for funerals. Michael Campion for example, was only 17 when joined the Army. A native of Church Street in the Liberties area. He died in Wexford on 25 July, killed in an ambush while escorting a train.[7]

Another, Volunteer Cuddell, a driver attached to motor transport in Wellington Barracks, was killed near Fermoy in Cork, with two other soldiers. A mine blew the Crossley tender he was driving, “to fragments” and “the right side of his face was almost blown away”. [8]

In Dublin itself, the young soldiers in the barracks found themselves policing a restive population, without training or guidance. Some died in accidents, such as Francis Denham, (18), who was mistakenly shot by another Free State soldier while on guard duty at Harcourt Street train station.[9]

Another boy soldier, Sean Sullivan, a Sergeant Major at only 16 years and 10 months, died in a scuffle while trying to clear a street outside a pub in the north inner city. The crowd, the Irish Times reported, “used insulting language to the officer”. He fired a shot over their heads, only for it ricochet back off a roof and kill young Sullivan. [10]

And all the time, menacing the raw, nervy young men, was the threat of attack. Most days, the troops in Dublin were ambushed with a sudden volley of shots, or a grenade thrown at a passing troop lorry. There were also regular sniping attacks on the barracks, which sometimes produced casualties.

Most days troops in Dublin were ambushed with shots and grenades

In one incident, a lorry heading back into Wellington barracks was ambushed at Curzon Street, across the South Circular Road. A grenade flew through the air, only to miss the troops and land in Williams’ newsagents. Maureen Carroll, a girl of only seven and another civilian were hit in the ensuing firefight.

The soldiers bundled out of their lorry and chased the ambushers down the maze of red brick streets. They caught them on Bishop Street. The troops claimed that the two, Sean McEvoy and John Hardwood, tried to “bolt”. Both men were shot in the back. One, McEvoy, died. [11]

The ambushers, like the soldiers, were not yet out of their teens, both were 19. As the above examples will show, the Irish Civil War, in this corner of Dublin at least, was fought by very young men. Of all the casualties listed in and around the barrack so far, none was over 20.

The Republicans

Who were the Republican guerrillas who were attacking the garrison of Wellington Barracks? By August 1922, the Anti-Treaty IRA had already taken two hard knocks in Dublin. In the initial fighting in early July, some 20 had been killed and another 400 captured by the Free State forces.

In late August, an IRA intelligence officer, captured in south Dublin, revealed plans of an operation destroying all the bridge s leading into the city, leading to the capture of another 100 or so Anti-Treaty fighters – this amounted to some 90% of their officers in Dublin. So by September they were down to four full-time guerrilla columns of ten men each with several hundred more part-time fighters. [12] With up to 90% of their officers arrested by August 1922, the IRA men in Dublin were young and inexperienced

What remained were often very young and inexperienced. The Dublin Brigade 4th Battalion (south Dublin), which was probably the one with which the Wellington garrison had most of its problems, had an active service unit in the city and there was also at least one flying column living rough in the Dublin hills.

Frank Sherwin, a 17 year old republican ,who had deserted from the Free State Army after the attack on the Four Courts, found them, in September 1922, tending their wounded from an attack on a barracks and avoiding the roads for fear of Free State patrols. Sherwin himself was attached to a group of 6 Fianna members, who lived in the mountains for a while but then came back down to the city, where they flitted from safe-house to safe-house. [13]

The activities of the republicans were minor in scale. Sherwin and his comrades robbed post-offices, destroyed communications and stuck up grocery stores for supplies. The flying columns could snipe at barracks and mount small scale ambushes, but were not in a position to take on the Regular troops in prolonged fighting.

Rather their aim was to obstruct the establishment of a working Free State Government by sabotage and attrition. This disruption of everyday life does not appear to have been popular in Dublin. Frank Sherwin remembered, “most of the people were against us in the civil war”. [14]

Why, given this situation, the Republicans were fighting at all, is a puzzling question. However, suffice to say, for the purposes of this article, that they believed they were waging a defensive struggle against a regime that was dismantling the Irish Republic. For many of them, the Free State’s attack on the Four Courts was the catalyst for them taking up arms against the new state.

While much of the Anti-Treaty IRA activity in the Civil War appears anarchic, it was actually directed to some extent. The orders for small scale attacks, destruction of communications and robberies for funds came from Liam Lynch, the IRA Chief of Staff, via Ernie O’Malley, Eastern Commander, to the officers on the ground. While they had little actual control over how men acted on their orders, there was a hierarchy at work among the guerrillas.

The Dirty War

Combating the Republican guerrillas meant finding out who they were, where their safe-houses were located and then arresting or killing them. This was primarily the job of Charlie Dalton’s Intelligence Department.

Most of them had been part of Michael Collins’ select band of assassins in the IRA before the Truce with the British. Now they used the same methods to terrorise the Anti-Treaty IRA guerrillas in Dublin. Dalton’s men raided houses used by suspected Republicans and brought the suspects themselves back for interrogation to Wellington Barracks.

By September 1922, 140 prisoners were held behind barbed wire in the barracks by November the number was 250. A number escaped; a tunnel was found from the prison camp in October, emerging on the other side of the Grand Canal, along with over 200 rounds of ammunition. But of those who remained imprisoned there, disturbing stories soon emerged of the treatment they had received. Disturbing stories soon emerged about the treatment of prisoners in Wellington, but some of those brought there never came out at all

On Saturday September 30th, an urgent request was sent to nearby Mount Argus Church for a priest to see a prisoner, Fergus Murphy. He had been wounded in the head. The priest, Kieran Farrelly, raced to the barracks, but troops there told him: “it’s nothing, a minor scalp wound”. Unconvinced, he went looking for Murphy among the prisoners. Standing at the barbed wire, he found him,

“As he drew near, I had a sickening feeling, because I had never before seen a man after torture. His head, from the eyes and ears upwards, was heavily bandaged. His eyes were blacked and twitching with pain. His face on both sides of the nose was also black. His right cheek was terribly swollen”. “I asked him what had happened him. He motioned to the Intelligence Department and said, “They took me down there last night and left me as you see me”. [14]

Some of those taken to Wellington never came back at all. On October 6, 1922, Dalton arrested three youths in Drumcondra, putting up Republican posters and brought them to the Barracks for questioning. They were interrogated by officers there and then discharged. The following day their bodies were found at the Red Cow in Clondalkin, shot in the head. Edwin Hughes and Brendan Holohan were 17. Their friend, Joseph Rogers was a year younger. [15]

An inquest was held the following month, prosecution counsel asked for a verdict of murder to brought against Dalton. The Jury, perhaps afraid of crossing the Army, declined. In fact, Dalton was put under arrest by the CID, a police counter-insurgency unit largely made up of former IRA men, with an equally grim record, but never charged. [16]

The Intelligence Department was not subtle, but, despite complaints that they preferred raiding to intelligence work, it was effective. They had extensive knowledge of how the IRA worked in Dublin, being former IRA men themselves, had good contacts and other information was, quite simply, battered out of their prisoners.

This all led to the gradual arrest of most high ranking republicans. On October 31, for instance, they picked up Joseph O’Connor, the commander of the Dublin IRA’s 4th battalion, at his place of work. On November 4, 1922, they had an even bigger scalp, when they captured Ernie O’Malley, head of the IRA’s Eastern Division, in a raid on his safe-house on Aylesbury Road. In the firefight at the house, O’Malley killed one soldier and wounded another before being badly wounded himself.

The barracks was also the site for the first two Military Courts martial in Dublin on November 7th in which four IRA men (Peter Cassidy, John Gaffney, James Fisher and Richard Twohig) were sentenced to death. They were executed at Kilmainham Gaol on November 17th. Another court martial shortly afterwards at Wellington sent three more anti-Treaty Volunteers to the firing squad at Beggars Bush Barracks on November 30th. [17]

The attack on Wellington Barracks, 8 November 1922.

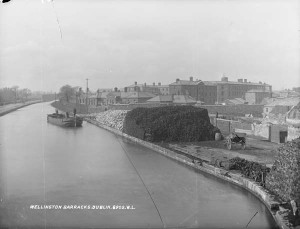

Early on the morning of November 8, 1922, the Republicans made their most determined attack on Wellington Barracks during the Civil War.

The attack seems to have been part of general “hit-up” by the Republicans in the city. other military barracks around the city were also attacked in the same week.

The Barracks’ orderly clerk was attending the morning parade, where the soldiers, mostly unarmed, were listening to the orders of the day, read by the regimental sergeant major. When he heard machine gun fire, the clerk at first thought it was practice firing. Then he saw spurts of dust spring up from the ground as the bullets landed around him. He flung himself to the ground.

Another soldier told the Irish Times, “ The first outburst crashed in on us just like a flash of lightening, and did most of the damage. All of us that could crawled around for cover, it was simply death to walk in the square at that time”

The Republicans had occupied the upper stories and roofs of the houses across the canal, at the back of the barracks. From there, they raked the parade square with gun fire. The sound was deafening to the stricken soldiers. One said, “It seemed as if marbles were being rained down from an immense height”.

The Republicans occupied houses across the canal and raked the parade square with machine gun fire

A total of 18 soldiers were hit. One was killed instantly and 18 badly injured, of whom one died later. As the firing started, a butchers van owned by one R. McGurk of Harolds Cross was making a delivery to the barracks. The storm of bullets peppered the unfortunate deliverymen, killing their horse and mortally wounding the driver.According to the soldier, “the whole thing lasted about 15 minutes, the rest of the soldiers came out then and started some Lewis guns going.”

One hundred soldiers had been lined up on the square shoulder to shoulder. The National Army thought the IRA had used a Lewis machine gun and told the press there were up to 40 attackers armed with rifles and machine guns. But in fact the IRA reports show that their squad, a party from the Dublin Brigade Active Service Unit or ASU, led by William Roe, had only eleven men, broken up into 4 parties and only two of these did any firing; 90 rounds with a Thompson submachine gun and 15 with a ‘Peter the Painter’ Mauser automatic.

The Republicans made their escape across country, through the villages of Kimmage and Crumlin, pursued by Free State troops. They were seen carrying two badly wounded men of their own. The Army later claimed the two were killed in the fire-fight, but there is no indication that this was true.

Listen to former Irish Army officer Declan Power talk about the attack on Wellington Barracks, below.

Reprisals

Free State troops flooded the area around Wellington Barracks after the attack and ambulances dashed to and from the hospital with the casualties. Most of the attackers had got away. But in the aftermath, the Free State soldiers managed to exact some revenge for the attack. In the aftermath of the attack, Free State soldiers managed to exact some revenge

James Spain was a local republican, who had participated in the attack. An hour after the gun battle at the barracks, he was spotted in the neighbouring streets, wounded in the leg, trying to find a friendly house.

A Mrs Doleman, of 22 Donore Road, was feeding her chickens, when a young man approached her, wounded in the leg, saying, “For God’s sake let me in! Jesus Mary and Joseph help me, if they get me they’ll shoot me!” She let him in, but hot on his heels was a Lancia armoured car with five soldiers in it. They pulled him out of the house. His body was dumped in nearby Susan Street, shot five times in the chest and head.

In the Barracks itself, according to IRA prisoner Joseph O’Connor, 250 prisoners were locked into the gymnasium, and in reprisal for the attack, National Army troops fired their submachine guns through the wooden door, mercifully only wounding five men. [18]

In sweeps of the immediate area, the Free State troops picked up another 20 or so Republican suspects. Among them was Frank Sherwin. He and five other youthful guerrillas had been carrying out attacks in Dublin, but not, apparently the one on Wellington barracks. When the soldiers burst into their safe house, they found five revolvers and six grenades.

Sherwin remembered, “we were marched to Wellington barracks, about a mile away. Some of the people on the street shouted and jeered at us. Perhaps they knew some of the soldiers who had been shot that morning”.

He was brought into the office of the Intelligence Department into the custody of Joe Dolan, one Charlie Dalton’s Squad men. There he was punched and kicked, to try to get the name of his commanding officer, Charles O’Connor. He refused.

“My clothes were dragged off me until I was naked…I was lashed for about twenty minutes”. The following day they tried again. They hit him in the head with a revolver and poked him with wire. Intelligence officer Joe Dolan jabbed him with a bayonet and stuck a rifle into his mouth. He even produced a razor and threatened to cut the prisoner’s throat.

In the end they decided he wouldn’t talk and threw him back in with the other prisoners. Sherwin recalled, “My face was swollen, my nose was broken, several teeth were missing and I had cuts and lumps on my head, with bruises all over my body. I could not stand or move for nine days”. He was never to fully recover the use of his right arm. [19]

Sherwin’s experiences, recorded in his memoir, show how the Intelligence Department used what can only be described as torture on prisoners. It seems to have had a dual aim – to extract information, but also to instill terror in the guerrillas still at liberty.

Epilogue

In terms of casualties inflicted, both killed and wounded, the 18 Free State soldiers hit in the attack on Wellington on November 8 represented the high point for the Anti-Treaty guerrilla campaign in Dublin. Two days later there were simultaneous, 20 minute attacks on both Wellington and Portobello barracks, including an attempt to kill National Army commander Richard Mulcahy, who lived inside the Portobello complex. Two civilians and one IRA man were killed in the attack on Portobello. A soldier was shot in the head but survived. [20]

On November 24, there was another “ineffective” sniping attack on Wellington that caused no casualties. In the new year, on March 29 and May 26, 1923, the republican night attacks put some more bullet holes in the walls of the barracks but failed to hit anyone. Two more sentries at the barracks were also shot and killed at close range in separate incidents in March 1923, but compared to the initial months of the war, casualties among Free State troops in Dublin had dropped steeply. [21]

The National Army was reorganised in early 1923 and Wellington’s role was considerably downgraded. its function as a holding centre for prisoners was discontinued in the new year and prisoners were now processed at either Kehoe or Portobello Barracks. The National Army Eastern Division was broken up into smaller more manageable commands and the new Dublin command and Intelligence Department were also moved elsewhere in the city in early 1923. Wellington now housed troops from the Railway Maintenance and Protection Corps (detailed to counter the anti-Treatyite’s campaign against the rail network). [22]

The National Army troops in Dublin, despite an improving organisational apparatus, never quite managed to squash the Anti-Treaty IRA in Dublin, but they did manage to reduce it to very small scale activities by the end of the war in May 1923. While street ambushes occurred almost daily in late 1922, by the spring of 1923, they had become a rarity. Two columns in south Dublin were rounded up in March and April of that year. In early May 1923, the National Army Intelligence service reported that the IRA, which had been perhaps 4,000 strong in June 1922, was down to 155 active men still at large, and those that remained were very poorly armed. The Fourth Battalion, for instance, now comprised of only 15 men with 8 guns. [23]

By the end of the war, some 81 prisoners had been officially executed by the Free State, and up to 150 more killed, like James Spain in on-the-spot reprisals. The Republicans lost because of insufficient military organisation and above all, lack of popular support

In Dublin the death toll amounted to about 250 on all sides. (See here). The total number of dead and wounded in the Civil War has never been counted, but we know that around 500-800 Irish Army soldiers were killed and over 450 IRA Volunteers lost their lives along with perhaps 2-300 civilians. Some 12,000 Republicans were imprisoned by the war’s end, around 3,500 of them from Dublin. Most of them, like Frank Sherwin, were not released until 1924.

The war in and around Wellington barracks is in many ways a microcosm of the conflict. First, fighting started considerably earlier than the official start in late June 1922 in disputes over the occupation of barracks. Second, the Republicans, were quickly beaten in conventional warfare and resorted to small-scale hit and run tactics. Although they had the option of amnesty, they pursued their campaign with as much vigour as they were able.

That they were unable to unseat the Free State was down to three main factors. First, they lacked sufficient manpower and military organization and training to do so. Secondly, the Free State proved willing to use the most draconian means at its disposal to put them down. Their troops, while far from elite, had enough local knowledge and, at times, ferocity, to accomplish this task. And thirdly, fatally for any guerrilla group, the Anti-Treaty IRA did not have sufficient popular support for its campaign.

Notes

[1] Wellington Barracks was situated on the South Circular Road, in central Dublin. It later became Griffith Barracks and later still, when sold by the Irish Army, Griffith College.

[2] Comdt. P.D. O’Donnell Griffith Barracks Dublin, Barracks and Post of Ireland, An Cosantoir, November 1978, Irish Times, April 13, 1922

[3] Paul V Walsh, The Irish Civil War, a study of the Conventional phase.

[4] Frank Sherwin, Independent and Unrepentant p18

[5] For Strength of the barracks see Military census online, entry for Wellington here. Irish Times, November 10, 1922 –an orderly sergeant at an inquest, for instance spoke with an English accent, though he defensively maintained he was an Irishman, and said he, “was no stranger to machine gun fire”.

[6] Irish Times April 20, 1922,

[8] Irish Times, August 31, 1922

[9] Irish Times, September 18, 1922

[10] Irish Times, October 21, 1922

[11] Irish Times, Spetember 13, 1922. The republican Wolfe Tone Annual 1962, lists McEvoy as, “murdered on the streets of Dublin after arrest”.

[12] O’Malley, No Surrender Here, p192

[13] Frank Sherwin, Independent and Unrepentant p15-18

[14] On the prisoner numbers and escape attempt see National Army Civil War papers, Cathal Brugha Barracks, CW/OPS/07/01 for the reports of prisoner mistreatment,Irish Times, October 7, 1922

[15] Wolfe Tone Annual 1962, p 25, Irish Times, October 19, 1922

[16] Eunan O’Halpin, Defending Ireland 49

[17] On O’Malley’s capture; Cormac O’Malley, Anne Dolan, No Surrenders Here, the Civil War papers of Ernie O’Malley, p350-353, for the Courts Martial at Wellington, John Duggan, History of the Irish Army (Gill & MacMillan 1991) p 101-102

[18] For the IRA report on the action see Twomey papers UCD p69/77 OC IRA Dublin 1 Bde to CS and p69/29 OC Dublin 1 Bde to Ernie O’Malley. For the National Army report see Military Archive, Cathal Brugha Barracks, cw/op/07/01 On the attack and the aftermath, including the killing of James Spain, Irish Times, November 9-18, 1922. For the firing on prisoners in the gymn, Joseph O’Connor Witness Statement Bureau of Military History, WS 544.

[19] Sherwin, Independent and Unrepentant, p18-21

[20] Irish Times, November 10, 1922

[21] Irish Times, November 24, 1922, March 29, 1923, May 26, 1923.

[22] National Army Civil War papers, Military Archives, Cathal Brugha Barracks (CW/P//03/06) and CW/OPS/07/03

[23] National Army Archive, Dublin Command Intelligence reports, General Reports No. 1 2 May, 1923 (CW/OPS/07/16)

John Dorney’s short book on the Irish Civil War is here

Podcast: Play in new window | Download