Who Shot Frank Lawlor? – Encounters with the Irish Civil War

John Dorney tries to make sense of a killing in December 1922 during the Irish Civil War

The Irish Civil War was a murky little affair, a dirty, vicious, half-remembered little conflict. Its name often rattles through the air in Irish politics, but only as a ghost.

It’s something that happened, that’s true, most people know that. But, at least in mainstream discourse, it is little mentioned. Certainly, the ins and outs of who did what to whom are but dimly remembered. The firmer, more corporeal memories of it have faded, forgotten by all those except the few, now very few, militant republicans with an interest in preserving it.

A nation, like a person, remembers what it wants to. The past changes, to suit what the present can imagine and understand and also live with

A nation, like a person, remembers what it wants to. And memory is alive, the past changes, not so much to suit the present, but in accordance with what the present can imagine and understand and also live with. But just like a person, a nation’s past traumas mark it and trouble it, even when forgotten. The very act of forgetting can tell us that the event is too painful, or even worse, too incomprehensible, to remember.

This piece is about two things, therefore. Some incidents from the civil war that have surfaced in my life many years after the war’s end, and secondly, the memory of these things.

Ambush corner

I grew up along the river Dodder, where Rathfarnham meets Terenure in south Dublin. If you follow the river past my house, along the green and leafy riverbank, and go past a triumphal arch, once erected as an entrance to Rathfarnham Castle, and walk up the hill onto Orwell road, you will find yourself on what still has the feel of a country lane. A golf course and the Russian embassy, with its extensive grounds, have preserved the trees and hedgerows that enclose the road.

I grew up along the river Dodder, where Rathfarnham meets Terenure in south Dublin. If you follow the river past my house, along the green and leafy riverbank, and go past a triumphal arch, once erected as an entrance to Rathfarnham Castle, and walk up the hill onto Orwell road, you will find yourself on what still has the feel of a country lane. A golf course and the Russian embassy, with its extensive grounds, have preserved the trees and hedgerows that enclose the road.

About halfway down, the road swings sharply to the right and at this corner, there is a little monument to a dead IRA man, Frank Lawlor, no more than knee high, written in Irish in the old Gaelic script.

As I was growing up, my father used to call this, “ambush corner”. He used to tell us that the IRA man had died in an ambush, fighting the British at this corner in the War of Independence. He would surmise, logically enough, that the corner was an ideal spot for an ambush.

It had plenty of cover, and a lorry full of British soldiers or Black and Tans or Auxiliaries would have had to slow down as it turned the corner, allowing someone to throw a grenade at it.

He used to tell us how he admired the “bravery, or stupidity, or whatever it was”, that led the young IRA man into the laneway where he died. Wise or unwise, he had died for Irish freedom, fighting bravely against the British. When, in the early 1990s, the original monument was destroyed in a car crash, he contacted the National Graves Association (which maintains monuments to dead Republican fighters from the 19th century up to the present) to get it repaired. And so it was, complete with its Irish dedication and script.

“In memory of Frank Lawlor, 1st Company, 3rd Dublin Brigade of the Army of the Republic, who was murdered on this spot on the 29th of December 1922”.

But Frank Lawlor did not die in action confronting the British Empire in pursuit of Irish freedom. My father must never have looked closely at the memorial, because if he had, he would have noticed at least the date, 29th of December 1922, by which time Lawlor, “of the Third Dublin Brigade in the Army of the Republic”, according to the inscription, would have been fighting not British troops, but those of the newly created Irish Free State, in the Civil War.

I noticed this when I was in university but for several years still imagined that Lawlor had died in a gun battle, during an ambush of Irish soldiers.

“Frank Lawlor did not die in an ambush, a close look at the inscription will tell you he was ‘murdered at this spot’ “

In those years, when I passed, I used to wonder at the futility of it. Gunned down in an attempt to kill Irish soldiers for a cause that seemed obscure, almost indecipherable.

But again, my imagination was mistaken, for Frank Lawlor did not die in an ambush at all. A closer look at the inscription, and perhaps an Irish dictionary, will tell you that, ‘Francis O Labhlar’, “a dunmaruscaid ar an laithir seo.” (“who was murdered at this spot”). Part of the confusion lies in the Irish word ‘dunmaruscaid’, (was murdered) bearing a passing resemblance to the English word, ‘ambush’. Another reason, of course is that ‘ambush’ was what I had expected to see.

What really happened to Frank Lawlor?

The story of Frank Lawlor had suddenly got much darker than I had imagined. The perpetrator, Lawlor, was now the victim. The righteous, the Free State soldiers, were now the murderers. The ‘fair fight’, I’d had in my mind, with grenades flying and shots exchanged had become an execution.

Still, for a while afterwards, I had no details. It was not until a few years later that I found some, on the internet. I had searched many times for an ambush on Orwell road and then for a killing of any kind there during the civil war, when finally I found a small mention, in a column of An Phoblacht, the republican newspaper, devoted to the ‘the cause’ and its many martyrs. [1]

Frank Lawlor, it told me, was abducted from his home in the city centre, shortly after Christmas 1922, shot and dumped at the bend in Orwell Road. One can imagine Lawlor being bundled out of a troop lorry or car in the dark, perhaps still addled by sleep, perhaps beaten, perhaps pleading for his life, pushed to his knees and shot in the head. The story of “ambush corner” had come a long way from its origins.

How did this happen? How could Frank Lawlor have been killed so coldly, perhaps by his former comrades in the pre-split IRA?

Answering this question requires a digression away from personal recollection and into the history of the Civil War in Dublin. The signing of the Anglo-Irish Treaty in December 1921 and its approval by the Dail in January 1922, caused the IRA, which had always been to some extent, a loosely coordinated network of guerrilla groups, to splinter in several different directions.

An anarchic time

It was an anarchic time, the period between the Treaty’s approval and the outbreak of civil war. The old RIC Police force was disbanded and British troops were first withdrawn to barracks and then in phases, evacuated from the country. Into the vacuum rushed a quarrelling series of armed Irish groups.

In January 1922, Michael Collins took over Beggars Bush barracks from the British and garrisoned it with IRA men loyal to him, who were to be the nucleus of the new Irish Army. Collins’ personal relationship with the IRA’s Dublin Brigade and particularly with ‘the Squad’, a small but murderous unit of assassins he had created, kept many of them loyal to the Provisional Irish government created by the Treaty.

Many of those who had done the most killing in Dublin in the War of Independence thus ended up on the Free State side in the Civil War.

On the other side, motivated perhaps by an idealistic pursuit of the ‘The Republic’ abolished by the Treaty, or perhaps by youthful intransigence, or perhaps by the arrogance of men with guns for civilian authority, the majority of the IRA (though possibly a minority in Dublin itself) rejected the Treaty and the Free State.

An Anti-Treaty IRA convention met in the Mansion House on Dublin’s Dawson Street in April 1922 and repudiated the right of the Dail to approve the Treaty. Shortly afterwards, around 400 Anti-Treaty IRA men, led by Rory O’Connor, a railway engineer from Dublin, occupied the Four Courts, that vast slab of Georgian columns and domes that stands along the Liffey and which then as now was the centre of the Irish judicial system.

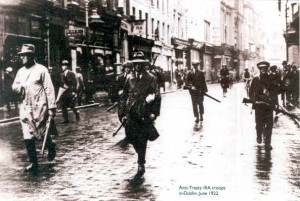

A famous photo of the time shows a heavily armed IRA party patrolling down Grafton Street, rifles trailing at their sides, some with hands reaching for revolvers inside their trench-coats and with hard, determined and set looks on their faces, staring out from under their nineteen- twenties-style hats.

O’Connor, who had been asked when leaving the Anti-Treaty IRA’s convention if his intention was to have a military dictatorship on the road to a re-born Republic, replied, “You can take it that way if you like”.[2]

On the same night as O’Connor’s men occupied the Four Courts, shots were fired under cover of darkness at pro-government troops guarding buildings around the city.

Looked at like this, the mystery becomes not how civil war between former comrades could have broken out, but why it took another two and a half months. For Collins and his colleagues in the Provisional Government did not attack the Four Courts garrison until the end of June 1922.

Moreover, reading accounts of the lead up to the outbreak of hostilities, one is struck by the air of unreality, as if neither side was yet taking the prospect of actual fighting seriously.

Vinnie Byrne, one of Collins’ Squad gunmen, was able to prevent Anti-Treaty fighters from occupying the Bank of Ireland, another grand Georgian building, once the seat of the Irish Parliament, by driving down there with a few men and persuading, gun in hand, the Pro-Treaty Volunteers there not to change sides. Oscar Traynor, an anti-Treaty IRA leader was waiting outside but didn’t interfere.[3]

The Four Courts garrison meanwhile sat in their building, fortified by fat legal books which they placed in the windows instead of sandbags and did nothing to prevent the establishment of the new government or its nascent army. Ernie O’Malley, at the time a harsh, even fanatical young guerrilla who was in military command of the Four Courts, wanted steps taken to take over the capital and force the British to re-start the war, but he went unheeded.

With the benefit of hindsight we can say that they sleep-walked into civil war, oblivious either to the consequences or to whether the result could even conceivably have been worth the cost.

Equally, on the other side, Collins, at heart a republican conspirator, tried to persuade the Anti-Treatyites to evacuate their positions peacefully. It took British pressure to finally edge the quarrelling groups over the precipice.

Henry Hughes Wilson, a retired British general, who had overseen the creation of Northern Ireland in 1921-22, was assassinated in London by two IRA men. At the time, Winston Churchill assumed it must have been the Anti-Treaty IRA in the Four Courts who were responsible and told Collins that if he would not assert his government’s control over its capital, British troops would do it for him.

Ironically or perhaps tragically, it now seems as if Collins himself was behind the killing.

In any case, the Four Courts garrison also supplied Collins with an appropriate excuse by kidnapping a Free State general and in response, Collins opened fire on the building with borrowed British artillery on June 28. [4]

Dublin Fighting

The set piece fighting in Dublin was over in just over a week. The Four Courts surrendered after two days of bombardment by artillery and the storming of the eastern wing of the complex by Free State troops. A massive explosion, captured forever in a photograph of a mushroom cloud rising over the Dublin quays, destroyed forever the records of local government in Ireland since the 12th century and also maimed up to 40 advancing Free State soldiers. It has never been truly proved whether the state archive was booby trapped, as the government claimed, or whether the bombardment set off the Republicans’ ammunition dump, as they were later to maintain.

The Anti-Treaty elements of the IRA’s Dublin Brigade also occupied the north eastern part of O’Connell Street, and several other places in the city after the fighting had broken out in the Four Courts. Over the following week their positions were slowly isolated and taken by the Free State forces armed with field guns and armoured cars.

The Anti-Treaty stronghold at the northern tip of O’Connell Street was bombarded and eventually set alight with incendiary bombs, forcing its defenders to evacuate it. Cathal Brugha, the republican leader, famously left the burning building last, alone and gun in hand, to die by Free State bullets. By June 7, the capital was firmly under government control and the remaining Anti-Treaty forces were dispersed southwards after a brief skirmish at Blessington, roughly 30 km to the south west of the city.

The fighting in Dublin was actually the largest engagement of the Irish Civil War, but it too, has a certain air of unreality, even playfulness, about it. On the surrender of the Four Courts, Ernie O’Malley and a youthful Sean Lemass, later Taoiseach of Ireland, surrendered to Free State troops but then simply asked to be let go.

The Provisional Government soldiers duly set them free. Liam Lynch, who would go on to command the Anti-Treaty IRA in the conflict, had a similar experience. O’Malley, while getting away over the Wicklow Mountains, was asked by a sheep farmer what all the trouble was about, “I think”, O’Malley recalled answering, “It’s about the next generation”.[5]

Liam O’Flaherty the First World War veteran and future short story writer, but then a communist who identified with the Anti-Treaty cause, fought in Vaughan’s hotel on O’Connell street, but escaped in time to watch Free State troops complete their taking of the street. Indeed, the government soldiers had to mount cordons to keep the crowds of onlookers away from the fighting.

Oscar Traynor, who commanded the Anti-Treatyites on O’Connell Street, towards the end of the fighting ordered his men to simply mingle into the civilian crowds and catch the tram to Blessington. Even Cathal Brugha, the republican martyr, was actually shot in the thigh, as the Free State soldiers wanted to capture rather than kill him, but bled to death as a result of a severed artery.

And yet the human cost of the fighting was real enough. Roughly 65 combatants were killed and several hundred injured and there were an estimated 250 civilian casualties of one kind or another. Around 400 Republican fighters were also taken prisoner. [6]

A Competition in Reprisals

What part Frank Lawlor played in these events I confess I have no idea. Nor do I know what he was doing as the civil war in the city become a low level, spasmodic guerrilla conflict.

In the months after fighting broke out, republicans would mount ambushes of Government troops in the city centre and at night would blaze away from rooftops of neighbouring houses at the thick walls of the city’s military barracks.

Fairly quickly, however, the relative mildness of the early weeks of the war disappeared and instead the conflict became a vicious competition in reprisals. Two events in August 1922 contributed to this.

One was the creation of the Criminal Investigation Department or CID, based at Oriel House in Westland Row. This was nominally a plain clothes police detective unit, but in fact was a 250 strong, mostly autonomous from the Police or Army and heavily armed unit manned by former IRA men, many of them from the ‘Squad’ or assassination unit, charged with putting down Anti-Treaty attacks in Dublin.

They did this by responding to attacks on their men with the brutally simple solution of finding and killing known republicans in reprisal. The second catalyst was the death of Michael Collins in an ambush in Cork on August 22. Collins had, on the whole, been a restraining influence on his men and his killing coincided with the first reprisals in Dublin. “The CID responded to attacks on their men with the brutally simple solution of killing known republicans“

Over the weekend after he was killed, four Republicans were found shot and dumped in remote areas around the city. [7]

This pattern was to continue until and indeed after the end of the civil war. Noel Lemass, Sean’s brother, disappeared in June 1923, a month after the end of the conflict and was found shot dead in remote spot in the Dublin Mountains in October of that year.

His memorial is on barren, windswept hillside, near Kilakee, in a little lane off the stony mountain road, surrounded by brown heather. Its inscription (written in English), simply states who he was, that he was “murdered at this spot” and that the monument had been “erected by his friends”. Twenty one Anti-Treatyites were killed in this way in Dublin in the conflict.[8]

The most harrowing story I have come across is that of two young Republicans (members of the Fianna or IRA youth wing), who were arrested in Dublin the day after Michael Collins’ death in an ambush in Cork. They were taken to a field in Whitehall, then, like the other killing locations, a rural townland, and shot. According to republican lore, they had buckets placed over their heads and asked repeatedly, “but what is it for?” as if they were facing an angry teacher and not an execution squad. [9]

Another three teenage Fianna members were arrested putting up posters in the city in September 1922 by troops under the command of Charlie Dalton, a former Squad member and now head of National Army intelligence. Their bodies were found in a field in Clondalkin.[10]

Martin Hogan, an Anti-Treaty IRA officer was arrested, killed and dumped, also in Whitehall, in April 1923. His girlfriend, who first tried to find him in one of the prisons, was told to enquire at Oriel House (CID headquarters), where she was told, “try the morgue”. His body was eventually found in a ditch in Drumcondra.[11]

I am struck by the vindictiveness of the reprisals, the cold cruelty. How did men who had almost light-heartedly allowed prisoners to walk free end up gunning down the most harmless representatives of their enemies?

One explanation may be the dynamics of guerrilla warfare. Confronted by an enemy who attacks and then disappears, the stronger side naturally lashes out at whatever targets are then available.

Besides which, the continuance of attacks on Government troops, in pursuit of a cause which must have seemed utterly futile as early as August 1922, when the Free State had taken all the major towns in the country, must have seemed like needless bloodshed to Free State soldiers.

On top of that, the Squad’s gunmen were used to the dynamic of revenge and had no doubt been brutalised by the repeated and close range killing they had done in the conflict against the British. It may have been no great leap to use the same violence against former comrades who were now enemies.

James Spain for example, a was seized and shot in revenge for an Anti-Treaty attack on Free State troops drilling in Wellington Barracks (now Griffith College) in November 1922, in which one soldier a civilian and two Anti-Treaty fighters were killed and 18 soldiers gravely wounded. [12]

State terror?

However, to attribute such happenings simply to undisciplined troops is to ignore another, rather better remembered aspect of the civil war. In November 1922, the Free State government passed emergency legislation allowing for the execution (with the signature of any two army officers) of anyone captured bearing arms against the state.

In December 1922, they began official executions in Dublin, with the shooting of four low ranking IRA members, followed closely by Erskine Childers, who had been the republican head of propaganda.

Eleven anti-Treatyites had been officially executed before the Republicans responded with the assassination of a pro-treaty TD, Sean Hales and the severe wounding of another as they were leaving a hotel on Ormonde Quay in central Dublin. They also issued orders, but never acted on them, to shoot unsympathetic judges and newspaper editors.

The day after the murder of Hales, an emergency cabinet meeting decided on the execution of the four republican leaders captured in the Four Courts; Rory O’Connor, Liam Mellowes, Joe McKelvey and Dick Barrett in response. “Government Ministers justified reprisals because they worked”

This was in no way legal, as the four had been captured months before the relevant legislation had been passed and in any case they could have had nothing to do with the killing of Hales, being in prison at the time. They were shot in equal parts as revenge and as a deterrent. Men who were ministers of the new Irish state, Richard Mulcahy, William Cosgrave, justified the executions because they worked – no more TDs were killed. Clearly the reprisal mentality was shared by government ministers as well as former Squad members.

Lawlor’s death in context

This brings me, finally, back to Frank Lawlor, killed on December 29th, 1922. His death, seen in the context of what came before, now looks unremarkable. The Republican Wolfe Tone annual of 1961 lists him as number 46 out of a total of 113 “unauthorised murders” of Republicans during the civil war. For good measure, they list another 77 “authorised murders” or executions and another 10 who died in imprisonment[13]

In the previous few days, there were several attacks on Free State troops in Dublin, including one on December 23 which fatally wounded a CID man. He died on December 29, the same day as Lawlor’s murder. [14]

Lawlor was number 46 out of what republicans called 113, ‘unauthorised murders’

Who exactly killed Lawlor and why he in particular we will probably never know, but it seems reasonable to suppose that he was killed in reprisal by National Army or CID men. Maybe they knew he had something to do with attacks on their troops, or maybe he was simply a known republican who fell victim to ‘one of them for one of ours’ logic by which the war was fought.

Through the testimony now available from the Bureau of Military History, we are now privy to rumours that Lawlor was killed in reprisal for the shooting of Seamus Dwyer, a former TD and a member of the Citizens’ Defence Force (an auxiliary police unit attached to Oriel House) on December 20th 1922.

According to Mary Flannerry Woods, an anti-Treaty Cumman na mBan activist, Dwyer, ‘was shot by the IRA as a spy and for whose shooting, Frank Lawlor was murdered on the golf links at Milltown.’ James Kavanagh, a friend of Dwyer’s, years later asked a pro-Treaty aquaintance if they had ever found who killed Dwyer, ‘he told me that they had … he couldn’t remember the fellow’s name but that his body was found in a ditch up at Milltown. The name of the man whose body was found in Milltown was Frank Lawlor, who from what I was told afterwards, could not have shot Seamus Dwyer as he was in another place when Dwyer was shot’.

The inquest into Lawlor’s death heard that he knew the CID were looking for him and they finally tracked him down to a friend’s house in Ranelagh on the night he was killed. Cahir Davitt the Advocate General of the National Army heard that, ‘a party of armed men, who described themselves as acting on behalf of “the Authorities”, called at the lodgings or a man called Francis Lalor and forcibly took him away. His dead body was found the following morning in the vicinity of Milltown Golf Course. This killing had all the appearance of being an “unofficial execution” carried out by some members of the Government’s forces’.

If Frank Lawlor was killed in revenge for Dwyers death, it appears, as Kavanagh suggested, that they got the wrong man, as according to IRA officer Sean Dowling it was another man, Bobby Bondfield who shot Dwyer, for which Bondfield was himself assassinated by pro-Treaty forces in March 1923. [15]

A memory that doesn’t make sense

In finding and remembering these bloody and depressing details, we are left with a double paradox. Two things that just don’t make sense. Firstly, these events have all but vanished from public memory.

We might expect, given that the defeated republicans of the civil war, or at least most them, came to be the dominant party in Irish political life in Fianna Fail, that the dominant popular perception of the civil war would be such admittedly small scale, but savage, repression.

But it is not. To the extent that the civil war is remembered at all, the dominant version is that of a noble, democratic, compromising Free State attacked by anti-democratic, militarist republicans.

I for example, having studied Irish history throughout school, left it with the impression that the republicans had started the civil war (which they didn’t, ultimately it was the Free State who fired first) and that the official executions were in reprisal for the assassination of TDs, when in fact the reverse was the case.

The more I looked into the civil war on my own, the more it was clear that the Free State side was guilty of at least as many, and probably rather more, of the war’s atrocities than its enemies (although, in yet another example of the popular amnesia that surrounds the period, the casualty figures of the war have never really been counted).

One reason for the official memory being rather ‘Free State’ is of course the effect of the political present on the past. With the Provisional IRA waging their campaign in Northern Ireland, in defiance of the southern state, the Republic’s political establishment was in no position to go into the nuances of a republican attempt to overthrow its predecessors back in 1922.

With advent of the peace process in Northern Ireland, Michael Collins was re-imagined as saintly figure, who accepted the value of compromise and peace, juxtaposed against the ‘intransigent’ and extremist’ De Valera. The real Michael Collins’ intentions towards Northern Ireland in 1922 were in fact rather hostile but this was either ignored or forgotten in the 1990s.

However, the second paradox is not the way the civil war is remembered but the fact that, despite many small reminders of it, such as Frank Lawlor’s memorial, it is simply not remembered at all. Whereas certain aspects of the 1916 Easter Rising and the 1919-21 War of Independence are prominent in public consciousness, the civil war is not. Most people are aware of its existence but very few know anything about the details. “The dead of the Civil War were never counted and certainly not celebrated.”

Whereas the Michael Collins, Kevin Barry and James Connolly are well remembered, Cathal Brugha, Liam Lynch and Liam Mellows are not. The dead were never counted and certainly not celebrated. The wars’ actions are not recalled in songs or stories as those against British have been.

The event is, I would suggest, simply much easier to forget than to remember. The struggle against the British can be imagined as having a point, a relatively clear structure and even a happy ending – the independence of most of Ireland.

The civil war can not be rationalised in this way. It had no clear aim to modern eyes and certainly no happy ending. In fact it barely had an ending at all. It simply fizzled out in May 1923. Moreover, once examined closely, the events do not flatter our perception of ourselves as plucky underdogs, nobly fighting a more powerful enemy.

The civil war tells us that we are vengeful, petty and cruel, that we would turn on each other and target the weak and those who couldn’t defend themselves. For this reason, Frank Lawlor’s place of execution can become, “ambush corner”. If we don’t know the truth we imagine it to be what we prefer it to be.

This brings me to my final point. It may be that modern Irish society prefers not to remember the civil war, in the way that people naturally prefer to repress uncomfortable and painful memories. However, in either the case of an individual or of a society, the event still happened. It still leaves its traces even if they go unremarked, perhaps even more so if they are not well remembered. So what effect did the civil war, this grubby and violent episode, have on Irish society?

It can’t be compared with, for instance, the Spanish Civil War of 1936-39, which amounted to a national calamity, with hundreds of thousands dead, hundreds of thousands more in exile, many more again imprisoned, ruined cities and which was followed by a prolonged period of near-famine and extreme hardship.

In Ireland the death toll was in the region of 2-4,000, probably closer to the lower estimate. The material destruction, while considerable, was never enough to seriously disrupt normal life. Dublin experienced a day or two of bread shortage in early July 1922 but that was all. Moreover, the civilian population was by and large not involved and were rarely targeted.

And almost incredibly, the government permitted its defeated enemies to participate in a fair election only months after the end of the conflict in August 1923 and all of the prisoners were released within a year of the war’s end. The CID was also disbanded and the Army’s size cut dramatically.

Nevertheless, it remains true that our state started out life with the use of official executions, internment, censorship and what amounted to tacitly approved death squads. In state papers that were eventually released in December 2008, it was revealed that the Free State Cabinet was aware of a group of Army officers (significantly Dublin Guards – former Squad members) known as the “visiting committee”, who were carrying out killings of prisoners in county Kerry (32 killed in March 1923). No action was taken and the papers were kept secret. There is no such direct evidence of whether the killings in Dublin had such tacit approval at top government level but certainly, no action was taken to stop them. [16]

An abusive state or an intolerant culture?

One is struck by the similarity with another recently revealed scandal, that of the Industrial Schools, in which thousands of children were secretly abused, physically and sexually over the first fifty years of the Irish state’s life. In both cases, extreme violence was tolerated and covered up by the state, carried out by groups (Christian Brothers or former IRA men) who had come from a culture of violence and obedience. One notes also that the Church was effectively an ally of the Free State in the Civil War, issuing in October 1922, a decree explicitly supporting the government and denying sacraments to Anti-treaty fighters.

The point here is not to invoke the enmities of the civil war in the state’s complicity in the Industrial Schools. Fianna Fail (the republican party) were, after all, in government for most of this time. The point is rather to highlight a strand of extreme intolerance in Irish nationalist life. The civil war came about because of a failure to communicate effectively and also a failure to peacefully tolerate difference within the nationalist movement. It was somehow easier to fight than to talk. “The civil war was a reflection of the worst side of ourselves and for this reason, best forgotten“

Once the civil war was on, the bitterness of its conduct appears out of all proportion to its causes, and once again, it was the government, backed by the church and with control of the press that was the most severe. It could be that Irish Catholic nationalism, for generations used to seeing the world as battle of its own community against outsiders, was intrinsically intolerant of dissent within its own ranks and was prepared to react with violence, if necessary, to restore conformity. Seen in this light, the civil war was a reflection of the worst side of ourselves and for this reason, best forgotten.

References

[1] An Phoblacht, August 31 2006, http://www.anphoblacht.com/news/detail/15742

[2 Michael Hopkinson, Green Against Green, the Irish Civil War, p67

[3] Hopkinson, Green Against Green, p75

[4] Hopkinson, Green Against Green, p121

[5] Ernie O’Malley, The Singing Flame, p55

[6] Niall C Harrington, Kerry Landings – An Episode of the Irish Civil War, p155, Tom Doyle, The Civil War in Kerry, p105

[7] Peter Hart, Mick, The Real Michael Collins, p412, O’Halpin, Defending Ireland p13-14

[8] Wolfe Tone Annual 1961, p24-27

[9] An Phoblacht, 31 August 2006, http://www.anphoblacht.com/news/detail/15742

[10] Eunan O’Halpin, Defending Ireland, The Irish State and its Enemies, p 14

[11] Nial Kelly, The murder of Captain Martin Hogan, IRA Commandant, 2005, http://www.belvederecollege.ie/History/History%20Award%202005.html

[12] Irish Times, November 9, 1922 and November 10, 1922

[13] Wolfe Tone Annual 1961, p24-25, My thanks to Michael MacDonncha for drawing my attention to this list.

[14] Jim Herlihy, Issues Effecting Irish Policing, http://www.esatclear.ie/~garda/issues.html

[15] For the statements of Kavanagh and Flannerry Woods, see here and here. For Dowling’s recollections, see Survivors, by Uinseann MacEoin, first published 1980, second edition, 1987. Publisher: Argenta Publications, 19 Mountjoy Square, Dublin 1, Ireland. Printed by The Leinster Leader Ltd, Naas, Co Kildare. p410 For the inquest see, Irish Times, January 1 1923, For Cahir Davitt’s statement see here.

[16] Irish Times, December 31, 2008

Post Script (2019)

When this article was written in 2010, there were very few means to track down the lives and IRA careers of ordinary volunteers such as Frank Lalor (the spelling on the monument is in fact mistaken). However with the release of the Military Pensions archive, we now have much more information on men like Frank Lalor, whose file (DP520) is now online.

I considered updating the article with all the new information but decided it would ruin the tone and flow of the original article. Instead, here is a summary of what the pension file tells about Francis Lalor.

He was resident in his family home at Rugby Road in Ranelagh, Dublin, and worked as an auditor at the Irish Agricultural Organisation in Merrion Square. His father had been a policeman in the Dublin Metropolitan Police. Frank joined the Volunteers (3 Battalion Dublin Brigade) in 1917 and served throughout the War of Independence, as did his brother George. Frank by 1922 was the captain of D Company. Evidently, both brothers took the anti-Treaty side in the split of 1922 over the Treaty, though there is no information in Lalor’s pension file regarding the role he or his brother played in the Civil War before December 1922.

His Battalion commander Joe O’Connor stated to the pension board that while ‘on the run’ in late 1922, he was arrested at a house on Castlewood Avenue, Rathmines by Free State forces and shot dead at Milltown Golf Links.Nor was that the end of the family’s troubles.

According to his mother, Katherine, the CID raided the family home 6 weeks after the killing of Frank, looking for his brother George, who was also on the run. They threatened to shoot her husband and to blow up her house. In fact they did neither, but according to Katherine Lalor, her aged husband suffered fits for years after the incident due to the trauma of the raid.

George Lalor survived the Civil War, but suffered grievously from unemployment in the post civil war period. After several years of lobbying, he eventually secured a posthumous War of Independence medal for his late brother Frank.