Irish Clans in the Sixteenth century

By John Dorney

The word clan seems to have entered English via Scots Gaelic, where it was used to describe the social organisation in the Highlands, where it lasted until the late 18th century. But its origins are in Ireland, the cradle of Gaelic culture.

Clan (clann) is a Gaelic word, meaning ‘family’, though the Irish kin-based organisations were usually called ‘septs’ in English, from the Irish sliocht, or line. In this article though, I will refer to them as clans.

A Gaelic clan was a territorial group with a common name, who believed they were descended from a common ancestor – thus the O’Neills were supposed to descend from Niall, the O’Donnells from Domhnal and so on. The territory of the clan was their duiche – native place. A chief (ceann cine) was selected to protect the integrity of this territory and that of his kinsmen (fine).

The fine were bound to each other by the practice of fostering their children to each other, thus making concrete what was a very distant blood relation. Technically, the chief or lord was elected by the free men of the clan, but in practice, by 1500, the candidate with the most muscle (that is who had the widest backing and the greater amount of soldiers) tended to prevail.[1]

Election and succession

In theory, the holder of this office was elected by his kinsmen, but in practice, he was often selected by negotiation, brute force or outside interference.

In theory, the holder of this office was elected by his kinsmen, but in practice, he was often selected by negotiation, brute force or outside interference.

The Gaelic Irish practised ‘agnatic patrilineal descent’, in other words the membership of family included all those descended from a given ancestor on their male side. In the case of the MacCarthys, lords of what is now west Cork and south Kerry, this was Carthy, hence their name, ‘the son of Carthy’, or collectively, Clan Carthy – ‘the race of Carthy’. Each sept (branch) of this clan had a chieftain, with authority over his kindred and their territory.

According to George Carew, the Lord President of Munster in the late 1590s, election and the approval of an overlord (‘giving of the rod’) were equally important in the succession of a chieftain, ‘the rod avails nothing except he be chosen by the followers, not yet the election without the rod’[2]

In theory the head of Gaelic clan was elected by the ‘true kin’ from a wide pool of relatives.

One MacCarthy chieftain, Florence MacCarthy would in the late 16th century, tell the English that it was a title that, ‘the O’Sullivans and the rest of the gentlemen, freeholders and followers of the country laid on me’[3] However there were times where there was no election process at all. In the caseof the McCarthy Reagh lordship in Florence’s lifetime, succession was decided by negotiation within the ruling kindred, with a hierarchy of seniority being decided in advance of the death of a chieftain, without any reference to the inhabitants of their territory of Carberry.

A Gaelic aristocrat could therefore aspire to authority over a very wide kin group as well as over his dependants and tenants. This extended hierarchical kin group was a mixed blessing for a Gaelic lord. On the one hand, he was to receive protection and manpower from his ‘kindred and friends’ (which is the literal translation of fine).

On the other hand, the wide pool of potential successors to chieftainship in the Irish system was the source of endless conflict between the lord and kinsmen of equal rank. For this reason, the English described ‘tanistry’, or election of chieftains as a barbarous method of succession and generally attempted to impose primogeniture inheritance, by which the first son inherited both land and title from his father.

Upon accession of a new chief, the land was redistributed among the fine in a practice the English knew as “gavelkind”. These kinsmen were in return expected to feed the lord, maintain his residence, and give him military service in his “rising out” – though this was limited to a few summer months each year.

Although this system implied mutual obligations on behalf of all classes, it did not mean, as 19th and 20th century Irish nationalists would assume, that Gaelic society was egalitarian. In fact, Gaelic law laid down hereditary legal rank; descending from the derbh fhine (“true kin”) – those eligible to inherit the leadership, to the fine (“kin”) who collected tributes or rents and mobilised the lordship for warfare, to professional classes like clerics, doctors and poets, in service of the fine.[4]

Land and labour

Most of the land was actually held by smallholders, the “free men” of the clan who produced food for tribute or rent – they were referred to as biatach, food producers and their townlands as baile biatach, anglicised as “ballybetaghs”.[5]

Significant portions of the population, known as caoireacht or “creaghts”, were semi-nomadic, living with herds of cattle and driving them seasonally to fresh pastures where they constructed temporary dwellings.

Gaelic Ireland was a predominantly subsistence economy, with livestock – particularly cattle – used as currency. This was why cattle-raiding was so common in Gaelic Ireland. The countryside was very heavily wooded and covered with bogs.

Small areas of the best land were cleared for agriculture, with the result that the tilled area of a lordship tended to sprawl in a series of unconnected plots. The staple crop was corn, which had the considerable disadvantage that it was difficult to grow and easy to destroy. [6]

Gaelic society was densely layered by social class.

At the bottom of the Gaelic social order were the landless peasants, referred to by contemporaries as bodaigh or “churls”. When exactions in any area became too demanding (for example obliging them to quarter soldiers for too long) the Irish landless class would migrate to other areas, including the Pale, to escape them. During the 16th century Gaelic lords such as the O’Neills, Con Bacach, Shane and Hugh would attempt to solve this problem by tying this class to the land.[7]

A large unit such as Duiche Ui Niall (‘the O’Neills’ country’) was composed of many small clans or septs who owed loyalty to the same lord. Outside of a powerful clan’s own territory, it controlled a ‘country’ – Tir – which was populated by clans who acknowledged the supremacy of a major dynasty. The heads of these sub-clans were known as uirithe – “sub kings” (singular: ur-ri). One example is the O’Cahans of Derry, who provided the tribute collectors and standard bearers for the O’Neills.

The fragmented nature of a Gaelic lordship could be a serious liability. When faced with a military threat superior to his own, the Irish lord could only count for sure on the support of free men of his own sept, a fairly small number. Subordinate clans and those who owed him tribute – even rival branches of the derbh fhine – were liable to switch to the winning side in times of crisis. In fact, many successions within Gaelic clans were marked by debilitating feuding within the derbh fhine.

War and warriors

The power of a ruling sept relied, in the final analysis, on military strength, both to fend off the incursions from neighbouring lordships and on occasion to coerce their own followers into obedience.

It was for this reason that subordinate clans were required to quarter mercenaries and provide a ‘rising out’. George Carew made a report in 1600, at the height of the Nine Years War, on the type of military mobilisation that could be expected in the Clan Carthy area.

Firstly, there was the gairm slua, or hosting; ‘a rising, upon a warning given, of all the able men of the country; every man to be furnished with sufficient weapon and three days victuals; and for every default, to be fined at a choice cow or xx livres of old money’[8].

Next there were ‘gall oglaigh’ or ‘gallowglass’, paid warriors, usually of Scottish descent, armed with axes and broadswords and ‘charged on the country’ in time of war. The lower classes were not usually armed and mobilised by the Irish clans until the late 16th century. Instead Gaelic lords had come to rely heavily on mercenaries in their personal service.

By the 16th century, Gaelic lords relied heavily on Scottish mercenaries known as gallowglass,

Whole clans of warriors (“galloglass” – gall oglaigh – foreign warriors) were imported from Gaelic western Scotland and settled in the service of major clans – for example the MacSweeney sept in north Tir Connell (Donegal) in the service of the O’Donnells. The MacCarthys Reagh permanently quartered 2 gallowglass septs on their territory named the MacSweeneys and MacSheehys who, Carew recorded had been settled in Carberry by ‘Diarmuid an Dúna’[9].

In the 16th century, the galloglass were joined by “redshanks” from Scotland who were hired out by the clans of western Scotland and the Isles for the duration of the campaigning season. Indigenous Irish mercenaries known as buanachain also emerged, armed, like the galloglass, with two-handed swords and axes. [10]

Carew’s third category of Gaelic soldiers was ‘kernty’ (ceatharnaigh or ‘kerne’), ‘a company of light footmen’ who were quartered in the same way as the gallowglass. The kerne who acted as lightly-armed mobile infantry in contrast to the heavily armed Scots. As such, they were perfect for raiding and ambushes, which most warfare in Ireland consisted of. Finally, there were ‘musteroon’, ‘a charge of workmen put in upon the Earl’s own tenants both for their wages and victuals, for any work or building he wanted to undertake’[11].

The law

The Gaelic Irish were not, as the English claimed, lawless, but followed instead “Brehon law”, which was written down in the 8th or 9th century, and whose name referred to the legal caste breitheamh or Brehons.

The Brehons had to study the seanchas mor book of Gaelic law for up to 20 years – a code designed to arbitrate disputes between warring parties such as those caused by feuding or cattle-raiding, by a system of negotiation and reparations. Thus, if a member of a clan was killed by another clan, his relatives were entitled to demand an eraic or “body price” from the offenders.

The kin-group rather than the individual was responsible for paying fines and as a result the family was supposed to prevent kinsmen from committing crimes in the first place. For important members of the fine, this had the advantage that their kinsmen of the clan had to pay reparations for their crimes, giving them virtual immunity.

The price of an eraic was determined by the social importance of the individual killed. Only for the murder of a king (by the 16th century, this title was the equivalent of an important lord) did the law demand execution. While the English and Palesmen held this custom up as the definitive proof of Irish barbarism (murder being punished only by a fine), it was in fact quite successful in preventing low level violence such as cattle-raiding or feuding from producing out-and-out bloodbaths. It was essentially a way of limiting violence in a chronically violent society. [12]

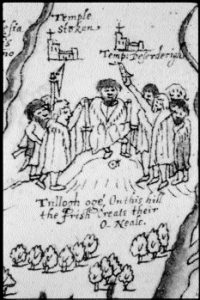

Gaelic lords arbitrated disputes via legal case known as breitheamh or brehons.

The Anglo-Irish lords also used Brehon law when convenient. The other function of the Brehons was to keep a record of the rights and tributes of lord to whom they owed allegiance. Thus the O’Neills had an ancient scroll laying down Ceart Ui Neill (O’Neill’s rights).

The Gaelic order was also buttressed by the poets and annalists, who like the Brehons, were hereditary classes, but who also had to study arduously to attain the status of ollamh or master. The learned classes wrote in an archaic formal dialect that was learned by the upper classes of Gaelic Ireland and Gaelic Scotland, between which the learned classes travelled freely. Their standard genre was “praise poetry” and satires, either flattering or disgracing a lord as the situation demanded. [13]

Gaelic Identity

The Gaelic Irish shared a common language (although different dialects were spoken in different provinces), a common culture and social system, and a common history of defeat at the hands of the English. Gaelic literature tells us that they identified themselves as Eireanach (Irish) as opposed to the English (Sasanaigh – “Saxons”) and as Gaedhil (Gaels) as opposed to Gaill (“foreigners” – the Palesmen).

We know that they resented the English slander of them as barbarians and pointed to their schools of bardic poetry, medicine and religion as proof of their civility. Indeed, most Irish lords had a command of Latin as well as Irish, though few in 1500 bothered to learn English. The Irish upper classes did not feel any sense of inferiority to the English, on the contrary, they were known to mock the Palesmen about their lowly ancestry.

Gaelic Ireland had a strong sense of cultural but not political identity.

An O’Neill chieftain is reported to have declared in Irish, when asked why he would not learn the language of the Pale, “thinkest thou that it standeth with O’Neill his honour to wryeth his mouth in clattering English?”[14]

However, the political unit of Gaelic Ireland was not the state, to which, in contemporary Europe the “political nation” (the noble elite) owed their allegiance. Still less was it “the nation” of later centuries to which every individual of an ethnic or civic group gave a more or less equal allegiance.

In Gaelic Ireland, the primary political loyalty of a person was to their clan or sept. For this reason, despite whatever cultural or ethnic solidarity they may have felt with one another, the Gaelic lords were just as likely to ally themselves with the English in times of conflict as with each other. Even within the major clans, because of disputed successions, it was fairly common for subordinate septs or rival family branches to co-operate with outside forces.

By 1500, the position of powerful Irish and Anglo-Irish lords had much in common. Both lived in stone castles. Both raised private armies (of Irish kerne and galloglass mercenaries). Both patronised Irish culture such as bards, poets and musicians (so for example, Old English as well as Irish lords began to have their military feats recorded and praised in Gaelic literature). Both engaged in fairly regular violence against one another and against urban settlements – mainly in the form of raiding and extorting protection money. They intermarried without ethnic distinction, so that Irish and Anglo-Irish lords were often related to each other.

The only real difference between them was that those dynasty descended from Anglo-Norman conquerors held their land with an English title –the Earls of Desmond, Ormond end Kildare for instance, and passed it intact, where possible to their eldest sons.

English policy on Clanship in Ireland

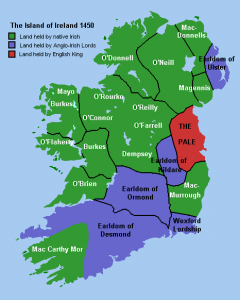

In 1500, most of Ireland was unde the control of independent, either Gaelic Irish or Hiberno Norman, lords.

In 1542, Henry VIII first began the process of conquering Ireland for the English Crown, declaring himself King of Ireland. A major part of this process was ending the Galeic social order of self-governing kinship groups.

What Henry Tudor needed was a cost-effective new policy that protected the Pale and England’s vulnerable west flank from foreign invasion via Ireland. What he came up with was an ambitious policy called ‘surrender and regrant’. Rather than rely on local Earls to police a half-conquered colony, Henry decided to extend Royal protection to all of Ireland’s elite without regard to ethnicity. In return the whole country would obey English law.[15]

All Irish lords were to officially surrender to the Crown and receive title to their lands by Royal Charter. Ireland was to be Kingdom rather a ‘Lordship’ as previously. What was intended to happen was that the Gaelic upper classes would become loyal subjects, abandon their ‘barbarous’ Irish ways, and gradually become assimilated into the English aristocracy. The analysis behind this policy was that Ireland’s chronic violence was caused by the permanent quartering of mercenaries by local lords (known as “bonnacht” to the Irish and “coign and livery” to the English).

Tudor English policy was to break the link between lords and their armed followers.

With all titles to lands regularised and legalised under surrender and regrant, this would no longer be necessary. Peace and civility would reign. The “common sort” would welcome the end of these “tyrannical” exactions and become model Englishmen themselves.

According to Richard Stanihurst, a Palesman, writing in the 1540’s, an English re-conquest would,

“reduce them [the Irish] from rudeness to knowledge, from treachery to honesty, from savageness to civility, from idleness to labour, from wickedness to Godliness, whereby they may the sooner espy their blindness, acknowledge their looseness, amend their lives, frame themselves pliable to the laws and ordinances of his Majesty whom God with his gracious assistance preserve, as well to the prosperous government of the Realm of England as to the reformation of her realm of Ireland”. [16]

Initially this was enforced by a type of military rule by provincial governors or ‘Lords President’ known as ‘composition’. However, the English shared with the Gaelic aristocracy a respect for social hierarchy. Important clans, previously the overlords in the region did not have to pay taxes to the Lord President. Rather, they were paid a set rent by other local landowners. The system of landholding was regularised, with legal rights accorded to local lords and freeholders.

While this had its disadvantages, it being difficult to assign landholding strictly to members of a Gaelic fine, who had previously shared a common territory, it was broadly successful in some areas in integrating the Gaelic lords into the English aristocracy. In many ways, it represented a legalised, demilitarised version of the old order. [17]

This policy would appear to support the argument that English officials in Ireland did not, initially, have a systematic policy to dispossess Gaelic Irish landowners per se, but rather to break the link between large landed estates and thousands of followers and dependants.

However, after the Second Desmond Rebellion (1579-1583), a new element was introduced: plantations, or the seizure of land and its settling with English colonists. A lord Deputy, Sidney, for example, wrote in 1583, advising ‘the dissipation of the great lordships; if among the English the better, if not, yet that they be dissipated’[1].

Widespread resistance to English rule, especially in Ulster, ultimately resulted in the dispossession of most of the native landowning class there. Even where this did not happen, however, the English, once their hold over the country became solidified after the defeat of Hugh O’Neill in the Nine Years War, abolished old Irish social system.

The legacy of the clan system

Life changed a lot in Ireland in the new century. New settlers introduced new methods of farming and even industry, opening mines, mills and iron works.

The old elite struggled to keep up with the entrepreneurial newcomers, often bankrupting themselves in the process and losing their ancestral lands. Nor were state land confiscations at an end, it became common practise to confiscate a portion of a native lord’s land and grant it to English settlers before giving him legal charter to the rest.

The old cultural order was definitively at an end. The Brehons, bardic poets and swordsmen struggled to secure a share of the much reduced patronage on offer – the rest were reduced to beggary or to exile.

The legacy of the clan system lasted probably into the 18th century.

The Irish language was no longer used in official business (although it remained the language of almost all the people) and Irish customs and dress were discouraged. One of the biggest changes in the new century was the elimination of private violence.

The English put an end to feuding, raiding and maintaining private armies on pain of death. Lords converted their fortified tower houses into renaissance mansions. The former Irish military classes were redundant and either became bandits (toraithe or “tories”) or emigrated as mercenaries to the continent. Even the landscape changed, Ireland changed in a century from one of the most wooded countries in Europe to one of the least – Irish oak being particularly in demand for the construction of ships.

However, some evidence appears to indicate that in estates that remained under their traditional leaders, little may have changed in the relationship between Gaelic lord and their followers in the first half of the 17th century. Take, for example, the following contemporary description of Viscount Muskerry (Donagh MacCarthy)’s mobilisation of south Munster during the rebellion of 1641-42;

‘He was left a plentiful fortune by his provident father, who contrary to the known custom of the natives of Ireland, was free from any engagement of mortgage or any other encumbrance… [he had] many kindred and a multitude of dependants…[and he] raised an army of his tenants armed with skiens, darts, javelins and pikes…[to join] that cause wherein his kinsmen and friends were already engaged’.[18]

Similarly, an anonymous writer in 1686 wrote of one chieftain, ‘Of all the MacCarthys, none was ever more famous than…Florence, who was a man of extraordinary stature (being like Saul higher by the head and shoulders than any of his followers) and as great policy with competent courage and as much zeal as anybody for what he falsely imagined to be the true religion, and the liberty of his country… his grandson and heir Charles is to this day owned and styled MacCarthy Mór’.[19]

Conceivably, it was only the upheavals of the Cromwellian conquest and the decimation of the Irish Catholic land-owning classes that finally ruptured this relationship.

References

[1] Sean Duffy, Ireland in the Middle Ages p17-18

[2] McCarthy, Daniel, The Life and Letter book of Florence McCarthy Reagh, Tanist of Carberry, Dublin 1867. Carew to Cecil, McCarthy, Letter Book p. 12

[3] Florence to Carew, May 14 1600, McCarthy, Letter Book p.281.

[4] Connolly, Sean, Contested island: Ireland 1460-1630, p.10-13

[5] Connolly, p11

[6] Lennon, Colm Sixteenth Century Ireland, p.35-40,

[7] Hiram Morgan, Tyrone’s Rebellion, p19

[8] Carew MSS vol.625, McCarthy, Letter Book p.222

[9] McCarthy, Letter Book p.217

[10] Lennon p55-56

[11] Carew MSS vol.625, McCarthy letter book p.222

[12] Duffy, p15, Allan MacInnes, Clanship, Commerce and the House of Stuart, 1603-1788, p2-4

[13] Lennon p62-63

[14] Stanihurst, Holinsed’s Irish Chronicles, p.17

[15] Lennon, p155-159

[16] Stanihurst, p116

[17] Lennon, 249-254

[18] J.T., Gilbert, Ed., Richard Bellings, History of the Confederation and War in Ireland, Vol. I, pp 67-68, 70.

[19] cited in O’Donovan, Florence MacCarthy to Thomond, This was the son of Daniel MacCarthy who converted to Protestantism.