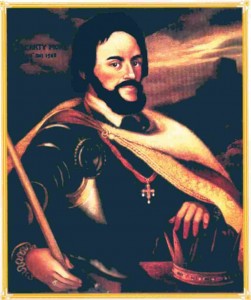

Florence MacCarthy, the last MacCarthy Mor, 1560-1640

John Dorney looks at the career of Florence MacCarthy, one of a generation of Gaelic aristocrats swept away by the Elizabethan English conquest of Ireland.

John Dorney looks at the career of Florence MacCarthy, one of a generation of Gaelic aristocrats swept away by the Elizabethan English conquest of Ireland.

Introduction – Survival in a whirlwind of change

Towards the end of the 16th century, Irish society underwent a series of social and political earthquakes.

The English state in Ireland, which had been slowly and painstakingly extending its authority over the island since the 1530s, suddenly and dramatically speeded up the process. Two devastating wars in Munster and Ulster and a host of other, smaller, conflagrations for the first time established the rule of the English Kingdom of Ireland over the whole island. In one short lifetime, from roughly 1570 to 1603 it managed to smash the native power-holders or co-opt them into its own legal, political and social system.

Two devastating wars established the rule of the English Kingdom of Ireland over the whole island

By the first decade of the 1600s, the traditional order had been turned upside down. Whereas in 1500, Ireland had been ruled by series of competing clan-based lordships, by 17th century all this had changed. The autonomy of the Gaelic and Old English lords was at and end – their private armies had been outlawed and they were subject to a central state based in Dublin. Some had lost their lands altogether and many more had seem them sub-divided among their kinship groups. The Irish legal system was outlawed, as was the traditional system of inheritance. Thousands of acquisitive settlers had arrived from England.

And of course many tens of thousands had died in the wars and rebellions that marked this process.

Alongside this – the English also brought with them a kind of cultural revolution. Whereas in 1500, the English had been worried about the Irish language becoming the lingua franca of the Pale itself, by 1600, the tide had been dramatically turned. Any lord who wanted to survive the whirlwind of change had to learn English, frequent the Court in London and even adopt English dress.

In a much more haphazard and much less successful manner, the English also brought with them the Protestant reformation – a fact that gave native resistance to the English state a religious and crusading character.

The Irish lords who found themselves in the way of the Tudor monarchy’s campaigns in Ireland were not nationalists as we would understand the term. Personal loyalty to the King of England was in their eyes, no disgrace. Rather, the problem they faced was one analogous to a series of gang leaders, used to small scale rivalry with each other, suddenly faced with the entry into their world of a military superpower, demanding obedience.

Irish lords had to duck and dive, adapt and conform, choose between the relative merits of rebellion or collaboration if they were going to survive

The rules of the game as they understood them were suddenly of no use. They had to duck and dive, adapt and conform, choose between the relative merits of rebellion or collaboration if they were going to survive.

One such lord was Florence MacCarthy – the last credible claimant to the title of MacCarthy Mor – lord over all the McCarthys and their dependents in the south of Ireland. His career took him in and out of rebellion, into the Tower of London as a prisoner, into the Court of Elizabeth I as a guest, into the hills of west Cork with his kerne and finally into captivity in London.

A look at his life can show how native lords tried to, at different times, resist, cooperate with and adapt to the arrival of the English state.

Florence MacCarthy, a short biography.

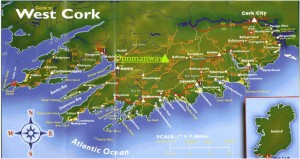

He was born as Finian MacDonagh MacCarthy in around 1560. He later acquired the name Florence during his dealings with the English. His father Donagh was the MacCarthy Reagh, chief of the McCarthy line of Carberry in modern west Cork and Kerry. Of the three McCarthy lordships, Desmond (McCarthy Mor lands), Muskerry and Carbery, the latter was the second biggest and the most fertile. The English authorities calculated that the McCarthys could muster about 5,000 fighting men if necessary, of whom the McCarthy Reagh of Carberry could command 1,200.

When Florence’s father died in 1581, he was succeeded as McCarthy Reagh by his Tainiste or Tanist (and Florence’s, uncle) Owen. It was understood however, the Florence would follow Owen as chief. At this stage, Irish lords held their position by two overlapping titles – by the Gaelic position of head of a clan or “sliocht” (line) and by an English title such as Earl – which had been granted to Irish lords in the 1530s.

At this time, the MacCarthy Reagh clan were much in favour with the English authorities – having sided against the Fitzgeralds of Desmond in their doomed rebellion against the English expansion into Munster. Florence led his kinsmen and followers on the English side in the later stages of the Desmond rebellion, and helped to drive the dwindling Geraldine forces out of McCarthy territory into northern Kerry.

He was arrested in 1589, not for committing a crime by because he had fallen foul of English policy

In later years Florence MacCarthy often cited his military record as proof of his loyalty to the Crown. In the short term Florence was popular with the English authorities in Munster, and was not looked on as a threat to the Plantation that was established in the aftermath of the rebellion. He was however reported to have learned Spanish and to keep the company of Spaniards on the south coast.

In 1589, Florence was arrested for the first time. He had committed no crime, but had fallen foul of English policy – to “dissipate” the military power of the indigenous lords. Put simply, the Lord President of Munster, Warham St Leger, feared he was making dangerous alliances and may become too powerful. Florence had proposed to marry Ellen MacCarthy, the daughter of Donal the McCarthy Mor, and would have been eligible to inherit the title of McCarthy Mor and to command all the McCarthys and their dependent clans.

St Leger, who had wanted Ellen to marry an English settler named Valentine Browne decided having the young MacCarthy, potential head of 5,000 armed men was too much of risk. For this reason, St Leger had him “restrained” and held in London “at discretion”. He spent 2 years in the Tower of London until Ormonde (an ally of the MacCarthy Reagh family) paid a bond of £1000 so he could live in freedom but within 3 miles of London.

In late 1593, Florence was allowed to return to Ireland. However the issue of his inheritance of either the McCarthy Mor title or the lands of the Desmond was not settled. Florence spent much of the next 6 years in legal wrangles with the Browne family – English undertakers who had taken possession of some of Desmond having mortgaged it from Donal, the McCarthy Mor.

Another enemy of Florence was Lord Barry, with whom Florence also had a longstanding land grievance. However, his most dangerous foes were within his own family.

His cousin, Donal na Pipi, MacCarthy Reagh, who had been passed over by Florence in Gaelic succession, wanted the English to grant him all of Carbery by English statute. Meanwhile, Florence also had a deadly rival for the position of MacCarthy Mor.

Donal MacCarthy, the illegitimate son of the McCarthy Mor, proclaimed himself the legitimate successor and took to the hills with an armed following to attack anyone who tried to fill the position or occupy MacCarthy Mor lands.

There was constant low level violence in south Munster in this period, with “wood-kerne” like Donal (always “the bastard” in Florence’s correspondence), making continuous attacks on English settlers such as the Brownes – possibly with the connivance of his father. Donal McCarthy Mor died in 1596.

Thomas Norreys, the Lord president of Munster subsequently pardoned Donal, despite his history as a rebel, to prevent Florence, who had a far greater following and landed base, from becoming McCarthy Mor.

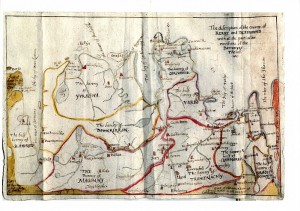

The English might have found a way to defuse these local conflicts in Munster, but instead the province was rocked by the importation of war from Ulster – the partly feudal Gaelic revolt, partly Catholic crusade led by Hugh O’Neill and High O’Donnell that we know as the Nine Years War (1594-1603). The war saw Florence MacCarthy’s years of triumph and disaster.

The Nine Years War saw Florence MacCarthy’s years of triumph and disaster

Hugh O’Neill sent mercenary contingents to Munster prop up local figures who might be sympathetic to his rebellion. He chose those who had either been ousted from lands and title by the English or who had lost out in internal power struggles, such as James FitzThomas Fitzgerald (the “sugan” Earl of Desmond) and Donal (“the bastard”) McCarthy Mor.

However, after correspondence with Florence, O’Neill switched his allegiance, recognising Florence instead. Florence, meanwhile, playing both sides off against each other, offered to secure the McCarthy territories for the English provided that they recognised his claims to the McCarthy Mor title and the lands of Desmond.

Despite being granted these requests, Florence received O’Neill on his coming into Munster and accepted a contingent of mercenaries. He was also in contact with Spain. He was probably instrumental in planning the Spanish landing at Kinsale in 1601, which lay within his territory and which he reconnoitred personally with O’Neill. And all the while he kept up a stream of letters to London and Dublin proclaiming his loyalty to Elizabeth I. In this way, he managed to get both sides to recognise him as MacCarthy Mor (or the Earl of Clancarthy as the English saw it).

By playing the Crown and rebels off against each other, Florence had both sides recognise him as MacCarthy Mor

The English authorities in Munster, especially the Lord President George Carew, were convinced that Florence was in rebellion. He insisted that the mercenaries were only to protect his “country”. During the fighting in Munster in 1598-1601, he tried to hedge his bets and helped neither FitzThomas (O’Neill’s main ally) and the rebels nor Carew and the English .

Florence’s forces fought only one skirmish in this time, ambushing an English expedition that was ravaging his territory in Carbery. Carew granted Florence a pardon for the attack on English troops, but resolved to bring him down at the first opportunity.

To this end, he recruited Florence’s “enemy within”, Donal “the bastard” MacCarthy, who changed sides from rebel to loyalist, to fight his family rival, Florence.

In 1601, when the rebellion in Munster had been crushed, Carew moved to arrest Florence and sent him, along with the rebel leader Fitzthomas, to the Tower of London. Searches of Florence’s papers discovered an extensive correspondence with O’Neill and the northern rebels. The arrest happened just a month before the Spanish landing at Kinsale and the war’s decisive campaign, in which the Spanish and rebel forces suffered a crippling defeat.

Florence was arrested a month before the Spanish landing at Kinsale in 1601

Florence was held from 1601 to his death in 1640 in varying degrees of captivity. For the remainder of his life, he continued to lobby to secure at least some of his inheritance in Carbery and Desmond. He was finally granted some land in Desmond in the 1630s, which was passed on to his sons.

The Gaelic order in south Munster. Adapting to change.

See also, The MacCarthys and the Munster Plantation.

The McCarthy lordships were a series of hierarchical kin groupings, with the ruling sept, or line, at the top. The power of chief figures like Florence McCarthy was essentially their ability to command the lesser septs to do their bidding. Some evidence shows that this was maintained by coercion – the first mention of Florence in the state papers is when he accompanied his father (and others like Donal na Pipi) on an expedition to “extort” food, drink and money off a minor chief in Carberry named Finian MacDermot.

At other times, there is evidence of mutual trust, for example, the inhabitants of Carbery appear to have been eager to host and foster Florence’s wife and young son during his first imprisonment. Later, Florence stressed in letters to Carew how he was obliged to keep an armed force to protect “his people” from violence during the Nine Years War.

Throughout his career, Florence was able to draw on his clan affiliations for support. While resident in Munster, he was able to call on a large “following”, and English sources warned he was “greatly embraced in Munster”. Even in exile in London, Florence maintained a large number of retainers, who were also for the most part McCarthys of Carberry or Desmond.

The Gaelic landed order differed from the English model, and the English found difficulties trying to adapt it. One aspect of this was the election of chieftains, which was essentially the securing of the approval of the most powerful of the dependent septs, notably O’Sullivan Mor in Florence’s case.

Throughout his career, Florence was able to draw on his clan affiliations for support

A powerful chieftain symbolically gave a rod to a successor to approve his election. Succession could also be imposed or given weight by an outside force, as in Florence’s case by Hugh O’Neill and the Catholic clergy of Munster. In introducing primogeniture inheritance (where everything went to the eldest son of the incumbent), the English disrupted the norms of Gaelic succession.

There was a long and bitter dispute between Florence and Donal na Pipi over whether the English grant of the MacCarthy Reagh lands should go to the incumbent chief and his heirs, or whether it must be passed on intact to the Tanist or successor. Florence wrote some letters defending Irish laws and customs such as Tanistry and his authority over “his people”.

This would indicate that there was respect for the titles of McCarthy Mor and McCarthy Reagh within Munster. Florence wrote that after Donal the bastard had been named McCarthy Mor by Hugh O’Neill, “the country people follow him in a manner”. Given Florence’s long absences from Carberry, his authority there could not be maintained by face to face contact with the inhabitants so his brother, Dermot Moyle, enforced loyalty among the inhabitants of Carberry.

Self-interest was always a more reliable predictor or Irish lords’ actions than was loyalty to principle.

However, at other times, Florence MacCarthy advocated the breaking up of the lordships, providing that he inherited the largest estates in Carbery and Desmond. Self-interest was always a more reliable predictor or Irish lords’ actions than was loyalty to principle.

Inter-clan violence remained a feature of life in south Munster during Florence’s lifetime. Even at the height of the Nine Years War, there were sharp skirmishes between the McCarthys of Carberry and O’Leary sept of Muskerry (followers of another McCarthy overlord) over stolen cattle. Significantly though, the English authorities, hostile to private wars, forbade Cormac MacDermot McCarthy of Muskerry to take revenge for the killings of his followers.

English policy in south Munster

English policy after the 1580s had two principle objectives. First, to remove powerful Irish lordships as potential military threats by breaking them up into their constituent parts. This involved granting landholding rights to minor chieftains and “freeholders” to eliminate the power of important chiefs to command large numbers of dependants. Secondly, to introduce English settlements into land confiscated as a result of the rebellion.

English policy was to break up the native lordships into smaller units and to introduce English settlements

This was left in the hands of “undertakers” who were responsible for settling allotted areas with English farmers and artisans. Both policies were pursued with the aim of introducing “civility” and “loyalty” to English government. This was understood to mean introducing the English language, law, dress and customs.

However, there was a lot of disagreement between the relatively liberal attitudes of men such as William Herbert and the more intolerant and militarist views of Warham St Leger and George Carew.

In practice, “reform” in south Munster was conducted in a very piecemeal manner, with intermittent bursts of repression. FitzThomas claimed that he went into rebellion because Irishmen could not get justice from English government, citing a long list of judicial killings of Irishmen by the authorities.

One settler wrote of Florence MacCarthy, “he cannot forget…the loss of so many of his near kinsmen and friends, if he would, his followers and kinsmen, who have ever been bloody and desirous of revenge, would never forget”. This shows the continuous low level violence that was taking place on the ground between the natives, planters and agents of the state.

Florence himself attacked “unjust” English policy in Munster, in particular his own lengthy imprisonments without charge.

The first Munster plantation appears to have been a rather chaotic affair on the ground. A report compiled in 1589 by St Leger showed that the number of English settlers imported by the undertakers was substantially below the number anticipated.

Furthermore the plantation was badly administered, with one undertaker being granted land already allotted to someone else, and, having transported a large number of workers from England, was obliged to return them there again.

Similarly, some Irish lords with legal title had their land confiscated in the plantation, and jury hearings had to be suspended for a period to make sure that Englishmen came to take possession.

William Herbert (himself an undertaker in Munster) complained consistently of the aggressive behaviour of his fellow colonists and English soldiers towards the Irish. He recommended a series of reforms such as the abolition of private troops allotted to the undertakers, the levying of new garrison troops, and the use of the Irish language for “reforming” the natives both to common law and the Protestant religion. For his criticisms of the undertakers, Herbert himself fell victim to campaign of slander form English soldiers, colonists and administrators.

The power of Irish lords was dissipated by granting rights to freeholders and minor lords whom they had previously dominated

In the aftermath of the Nine Years War, Carberry and Desmond were substantially bought or granted to English settlers such as the Browne family and Richard Boyle, the famous earl of Cork. Native lords such Donal “the bastard” and Donal na Pipi were also accommodated, although their authority over their followers and dependent septs was dissipated by the granting of independent land rights to “freeholders” and minor lords.

As Florence’s second period of imprisonment went on, it becomes clear in his legal correspondence that his former territories were now substantially held by Englishmen, not only because of confiscations, but also because native landowners commonly sold or mortgaged their patrimonies to settlers to raise money.

Cultural conflict and change.

Florence was educated by both Irish “ollamhs” and Catholic clerics of Old English extraction. He was highly proficient in writing English prose and in the use of English common law. Most of his correspondence, with the exception of his letters to the Ulster chieftains, was in English.

However, he made no discernible effort to introduce English “civility” within his own territory as the English were pressing lords to do. In his second imprisonment, he wrote a short history of Ireland in a letter to the Earl of Thomond. John O’Donovan commented in his translation from Irish that the author clearly had an excellent grasp of classical written Irish.

In his semi-mythological history, Florence defended the Irish from the charges of violence and barbarism, blaming the Anglo Norman baron’s lawlessness for subsequent rebellions.

He also stressed that the Stuart Kings (who succeeded the Tudors in 1603) were “of our nation” since the Scottish nobility were descended from the Irish. In common with contemporary writers like Keating and Lynch, McCarthy accepted the Stuart sovereignty over Ireland but hoped for fair treatment and respect for the Irish by the Scottish kings.

It is impossible to speak of nationalism in late 16th century Ireland, but there was a cultural and ethnic dimension to conflict.

It is impossible to speak of anything like nationalism as we would understand it in late 16th century Ireland – the idea that populations should give their loyalty to a state based on their cultural allegiance. First of all, most of the population did not have a choice – they had to follow the dictates of whichever landed power was in control of their locality. For the landed and noble elite the priority was the best interests of themselves and their families. Cultural solidarity came a very distant second.

Nevertheless, there was a cultural and ethnic dimension to war in the 1580s and 90s in Ireland. Florence MacCarthy, when trying to prove his loyalty to the English, dressed in English clothes and reported that he spoke English to the rebels in “searing speeches” on their duty of loyalty to the sovereign.

Donal “the bastard” MacCarthy, who spent most of his career attacking English settlers, tried to undermine Florence’s position among his MacCarthy kinsmen by spreading word that he was “a damned counterfeit Englishman”.

It was understood that such things as clothes, language and appearance were all markers of political allegiance. To support the Irish language (in the form of patronising Gaelic poets), wear Irish clothes and practise Irish customs was deemed by the English to be marks of “incivility” and “disloyalty”. Those in rebellion, by contrast, emphasised these things to attract support.

Religion

Florence was a Catholic, and was in touch throughout his life with relatives of his who were priests in Spain. Already, by the time of the Nine Years War, religion had become a battle line in Ireland –used as a rallying point for all those opposed to English influence.

It is difficult to judge the depth of Florence MacCarthy’s commitment to religion, however. The English governor George Carew mentioned that he was known for speaking disrespectfully to Catholic priests in public. It is most likely that they wanted him to take a more committed part in the “Holy Action” against the English, while Florence preferred not to commit himself openly to either side.

However, Florence was known to have hosted outlaw seminary priests in Carberry, and while in London was alleged to have facilitated the escape of several Irish catholic clergy to the continent.

Irish Catholic political identity was hardening but it did not yet dictate political attitudes.

As in many other ways, Florence MacCarthy’s religious outlook represents a society in transition. Irish Catholic religious identity as something distinct from the religion of the state was a fact that was hardening towards the end of the late 16th century. But it did not yet dictate political attitudes. MacCarthy’s neighbour, the Catholic Lord Barry, for example, refused to join the rebel side in the Nine Years War on the grounds that he had, “never been troubled for my religion”.

Political Allegiances.

See also, The MacCarthys and the Nine Years War.

It is difficult to speak of firm political allegiances among the Irish lords of late 16th century Munster. Virtually all of them were in rebellion at some point, professing in their letters zeal for the Catholic religion and for the “liberty of their country”.

However, the same people are almost always to be found fighting on the English side at other times, against neighbouring lords or even rival members of their own sept. Typically, the actions of Gaelic aristocrats were motivated solely by whether their personal interests were served by one side or the other.

Gaelic aristocrats were motovated almost solely by their personal interests

Similarly, it was commonplace for them to change sides during a conflict to remain on the winning, side. Florence was no different to the others in this respect, alternately pledging his allegiance in the Nine Years War to the rebels and to the government, causing both sides to complain of his faithlessness.

However, Florence may perhaps be defended from charges that he was utterly unprincipled. His responsibility as McCarthy Reagh tanist and MacCarthy Mor was to militarily protect his “followers and dependants” who lived in Carberry and Desmond. Throughout his career, Florence’s actions could be seen as being consistent with this principle, driving the Geraldine rebels out in the 1580s, keeping out English forces during the Nine Years War and accepting a rebel contingent on his own terms.

He does not seem to have succeeded in saving his lands from destruction however. Carberry was “considerably wasted” by the end of the war.

Conclusion

Florence McCarthy’s generation of Irish lords was the last to grow up in society that was still largely Gaelic in culture and social structure. The Elizabethan English state engulfed them in a tidal wave of change; military, political, social and economic.

Most, like Florence MacCarthy, did whatever they could to survive the storm and emerge on the other side. Many, like him were instead swept away.

This article is based on an MA thesis. Longer and footnoted versions may be made available on request.