Today in Irish History, January 3, 1602, The Battle of Kinsale

The Decisive battle of the Nine Years War. By John Dorney

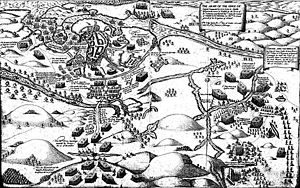

On Christmas Eve 1601 by English reckoning and January 3 1602 by Irish and Spanish calculation[1], Irish, English and Spanish soldiers met in battle outside the town of Kinsale on Ireland’s southern coast.

Musket shots rang out, tearing into tightly packed ranks of pikemen, horsemen slashed at foot soldiers with their swords, the infantry levelled their pikes en masse to ward off the cavalry.

The engagement marks one of the great turning points in Irish history. By the end of the day the Irish forces of Hugh O’Neill and Hugh O’Donnell were streaming back northwards in defeat, the Spaniards at Kinsale were preparing to surrender to the victorious English forces of Lord Mountjoy.

‘Immense and countless was the loss in that place, although the number slain was trifling; Annals of the Four Masters on the battle of Kinsale.

The Annals of the Four Masters later lamented;

‘Immense and countless was the loss in that place, although the number slain was trifling; for the prowess and valour, prosperity and affluence, nobleness and chivalry, dignity and renown, hospitality and generosity, bravery and protection, devotion and pure religion, of the Island, were lost in this engagement”.[2]

To Kinsale, the Annals and most subsequent accounts attributed the final success of the English conquest of Ireland and the demise of the Gaelic order and eclipse of the Catholic religion. Kinsale was a battle, the Annals wrote, fought for ‘their patrimony and religion’ and the Irish had lost. The future belonged to the English, Protestant Kingdom of Ireland.

But was the background to and the outcome of the battle of Kinsale so straightforward? Hugh O’Neill who led the Ulster Irish forces had once been a staunch ally of the English Crown. Among Mounjoy’s English forces was Barnaby O’Brien the Gaelic Irish (and Catholic) Earl of Thomond.

What was really fought for at Kinsale and who really won?

The Nine Years War

The English Tudor monarchy needed to secure Ireland to prevent it from falling into hostile foreign hands. This question was especially pressing following Henry VIII’s break with the papacy, leaving England exposed to a possible Catholic counter attack.

To this end, Ireland was formally made a Kingdom in 1542 and the English spent a century by turns conquering, colonising, but also trying to assimilate the native Irish lords into obedience. Ireland was a patchwork of militarised lordships, both Gaelic Irish and ‘Old English’ (or Hiberno-Norman) in origin as well as the odd pocket of fortified English settlement such as the towns of Dublin, Wexford or Cork.

Irish lords had to choose between resistance to the advancing state based in Dublin, assimilation to its demands and in return being granted English titles, or as many chose instead, a combination of the two.

The 16th century saw the expansion of English authority in Ireland at the expense of the native lords.

What followed was a near century on of on-off warfare. In Munster, two Desmond Rebellions saw the bloody smashing of the Fitzgerald dynasty in the 1570s and 80s. By the 1590s, the English project was beginning to penetrate Ulster, which was controlled by the usual complex collection of clans and lordships, but predominantly by two dynasties, the O’Neills of Tyrone and O’Donnell’s of Tirconnell.

Hugh O’Neill, the Earl of Tyrone had been brought up by a foster family in the English Pale around Dublin, was fluent in the English language and even conformed to the Protestant Church for a time. During the Desmond Rebellions he had fought on the English side. But he had also waged a bloody decades long internal struggle within Tyrone to make himself lord of the O’Neills and was not about to hand over power in the north to an English sheriff and to reduce himself to the status of simple landlord.

His close ally, Hugh O’Donnell, Earl of Tyrconnell began what the English called Tyrone’s Rebellion and the Irish the Nine Years War in 1592 by driving out the English garrisons in what is now Donegal. The following year he and Hugh Maguire of Fermanagh began attacking English outposts all across south Ulster.

At first, O’Neill stood aloof from the rebellion, although he was directing proceedings, hoping as a compromise to be named as Lord President (governor) of Ulster himself. Elizabeth I, though, had correctly perceived that O’Neill had no intention of being an English-style landlord.

Rather, his ambition was to usurp her sovereign power and be she thought, “a Prince of Ulster”. She refused to grant O’Neill provincial presidency or any other delegation of power which would have given him authority to govern Ulster on the crown’s behalf. She also had scathing words for his ingratitude, he, as far as she was concerned, having been raised into his position by English benevolence. [3]

In 1595 Hugh O’Neill joined his confederates in open rebellion by attacking the English fort on the Blackwater River. It was also in this year that Hugh was inaugurated The O’Neill at the traditional O’Neill inauguration site at Tullaghoe. It was a formal rejection of English authority. As one contemporary put it, “Tyrone [Hugh’s English title] was a traitor, but O’Neill none”.[4]

The Nine Years War began as a regional dispute but ended as holy war.

With Spanish arms, money and training, O’Neill and O’Donnell created a formidable military force. In 1598, their forces crushed an English army at the Battle of the Yellow Ford in County Armagh. For a time it seemed as if Ireland was in their grasp.

By now, they were publicly calling their war, not a private affair for local power, but a holy war to free Ireland of Protestant English rule. To the mostly English-speaking but Catholic townsmen of Dublin he wrote that he was fighting for,

“the delivery of our country [from] infinite murders, wicked and detestable policies by which the kingdom was hitherto governed, nourished in obscurity and ignorance, maintained in barbarity and incivility and consequently of infinite evils which are too lamentable to be rehearsed”.[5]

And to the southern Irish lords he wrote,

“I would come to learn the intentions of all the gentlemen of Munster regarding the great questions of the nation’s liberty and of religion”.[6] By 1601, O’Neill wrote to Florence McCarthy, his ally in south Munster, hoping “that you will do a stout and hopeful service against the pagan beast… our army is to come into Munster and do the will of God”.[7]

Pressure on Ulster

Many Irish lords though, simply did not trust O’Neill, whom they had always known as a wily and self-interested player of power politics. Others calculated that the English would ultimately win and that therefore their best interests lay in siding with them. So, many lords and most of the walled towns did not join O’Neill and O’Donnell’s crusade.

By 1601, the attempts to spread the war all over Ireland were faltering and the rebellion’s stronghold in Ulster was under pressure.

The English managed to quash the rebellion in the southern province of Munster by mid-1601 by a mixture of conciliation and military force. The two principle rebel leaders there, James Fitzthomas and Florence MacCarthy were arrested and sent to the Tower of London, where both of them eventually died in captivity. Most of the rest of the local lords submitted once O’Neills forces had been expelled from the province.

The main war however, was in the north. Lord Mountjoy the English commander managed to penetrate the interior of Ulster by sea-borne landings at Derry and Carrigfergus, while trying himself to break through overland through south-east Ulster. His commanders, helped by Niall Garbh O’Donnell, a rival of Red Hugh, devastated the countryside, killing the civilian population and their livestock and destroying crops. Although O’Neill managed to repulse another land offensive by Mountjoy at Moyry Pass near Newry in 1600, his position was becoming desperate by late 1601.

Spanish landing

It was at this point, in September 1601 that the long-promised Spanish expedition finally arrived in the form of 3,500 soldiers under Don Juan del Aquila, landed at Kinsale, County Cork, virtually the southern tip of Ireland. Ireland had featured in Spanish plans to invade England in 1588, but in the event its involvement with the ‘Invincible Armada’ was mostly limited to Irish lords (including Hugh O’Neill himself) opportunistically attacking Spanish shipwreck victims in its aftermath.

The Spaniards landed at Kinsale in September 1601 to aid Hugh O’Neill and his allies

Now though, the rebel alliance, supported by Irish Catholic Bishops successfully lobbied Phillip II of Spain for an invasion of Ireland to aid their fellow Catholics and to strike at Elizabeth I, who was aiding Phillips rebellious Protestant subjects in the Netherlands. An armada was assembled in Lisbon in 1596, but never set sail. In 1601, under the new King Phillip III a more modest force was finally dispatched to Ireland.

O’Neill had broached a landing in Munster with the Spaniards, but only if the force was over 6,000 men. If less, he had wanted them to come directly to the north, but bad weather forced the Spaniards to land on the Cork coast, much to O’Neill and his allies’ dismay.

At Kinsale, the English commander Mountjoy immediately besieged them with 7,000 men, while a naval fleet blockaded the harbour to block any reinforcements from Spain. O’Neill, O’Donnell and their allies marched their armies south in freezing December weather to sandwich Mountjoy, whose men were starving and wracked by disease, between them and the Spaniards.

Kinsale has become an iconic battle in Irish history, and rightly so. It did not end the war and it did not by itself destroy Gaelic culture or the Gaelic aristocracy, but it decide the future outcome of the war and therefore of the English presence in Ireland.

After Kinsale, the chance of an Irish victory had passed, and the question was not whether Ireland would be English, Spanish, or independent, but what terms the rebels could hold out for.

Battle

For such a historical turning point it was a rather confused and inconclusive battle. The Irish advanced in a driving thunderstorm, but their attack stumbled on the advancing English cavalry, and part of the Irish infantry panicked and fled. They were then pursued for miles by the English horse who killed several hundred of them. Though most of the Irish forces of some 8,000 men was unaffected, they retreated in disarray and the planned joint attack with the Spaniards never came off.

Generally Irish tactics up to Kinsale had relied on guerrilla warfare or defence of carefully prepared defensive positions. At Kinsale they had tried to march into battle in tercios, large square of pikemen and musketeers and had come to grief.

The Spaniards reported that the Irish weakness was lack of regular discipline, one writing, ‘if the Irish had resisted just half an hour instead of withdrawing… we would have won a renowned victory and… expelled once and for all the English from Ireland…But there is no discipline among the Irish. They have made war so far by ambushes in tough territories… and do not know how to make the squadron’.

The Annals thought the problem was rivalry between O’Neill and O’Donnell, which threw the Irish forces, advancing towards Kinsale into confusion,

Manifest was the displeasure of God, and misfortune to the Irish of fine Fodhla [Ireland], on this occasion; for, previous to this day, a small number of them had more frequently routed many hundreds of the English, than they had fled from them, in the field of battle, in the gap of danger, up to this day.

For such a historic turning point, the battle of Kinsale was an undistinguished encounter.

The English claimed that they had killed up to 1,200 ‘rebels’ but one Irish source, Philliip O’Sullivan Beare, put the Ulstermen’s casualties as low as 200. Nevertheless they retreated back north in defeat and disarray. English losses in battle are hard to determine, as many more of their men died of disease during the siege of Kinsale than on the field itself. In the battle on January 3, they claimed to have lost only three men killed. But Carew, the English Lord President of Munster reported to his superiors that about 6,000 of his English troops had died during the siege.[8]

The remainder of the Irish withdrew as did the Spaniards, who surrendered in an orderly fashion days later and were allowed to return to Spain.[9]

The Irish, amid bitter recriminations among their leaders for the defeat, headed home to Ulster to defend their own lands.

Donal O’Sullivan Beare, their only important ally in the south by this point, held out in his territory in Kerry for several more months before fleeing for Ulster himself with his kinsmen and followers. Hugh O’Donnell left for Spain, where he died in 1602, pleading in vain for another Spanish landing. He left his brother Rory to defend Tir Connell.

Both he and Hugh O’Neill were reduced to guerrilla tactics, fighting in small bands, as English commanders Mountjoy, Dowcra, Chichester and Niall Garbh O’Donnell swept the country, burning and killing as they went. Mountjoy smashed the O’Neills’ inauguration stone at Tullaghogue.

With a secure base in the large and dense forests of Tyrone, O’Neill held out until 30 March 1603, when he surrendered on good terms to Mountjoy. Had he known that Elizabeth I had died a week before, he would probably have struck an even harder bargain. As it was, he wept with frustration on hearing the news.[10]

He left Ireland in the ‘Flight of the Earls’ in 1607, never to return. His defeat at Kinsale in January 1602 meant that we will never know if he was really an Irish patriot, Catholic crusader or self-interested warlord. It is possible to say that at different times in his career he was all three.

The battle of Kinsale did not mark the end of Gaelic Ireland on its own. But it did mean that the future of Ireland would be in English hands.

References

[1] The English were still using the Julian calendar and the Spanish the newer Gregorian one.

[2] Annals of the Four Masters, http://www.ucc.ie/celt/published/T100005F/

[3] Hiram Morgan, Tyrone’s Rebellion, the Outbreak of the Nine Years War, 1993. p177-178

[4] Morgan, Tyrone’s Rebellion p189,

[5]Hiram Morgan, Hugh O’Neill and the Nine Years War in Tudor Ireland, The Cambridge Historical Journal, 1993, 21-27

[6] McCarthy Daniel The Letter Book of Florence MacCarthy Reagh, Tanist of Carberry, p227

[7] O’Neill to Florence MacCarthy, 27 January 1601, (Cal. S.P Ire 1601-1603, p.392)

[8] For the Spaniard’s opinion on the battle see Oscar Recio Morales, Spanish Army attitudes to the Irish at Kinsale, in The Battle of Kinsale, 2001, p96-97. For the battle itself see Hiram Morgan, Disaster at Kinsale in Ibid. p.128-130. See also John McGurk, The Battle of Kinsale, History Ireland, 2001, http://www.historyireland.com/early-modern-history-1500-1700/the-battle-of-kinsale-1601/

[9] Sean Connolly Contested island: Ireland 1460–1630, Oxford University Press, 2007 p 252, Colm Lennon Sixteenth Century Ireland – The Incomplete Conquest, Gill & Macmillan, Dublin 1994 p300-301

[10] Lennon, Sixteenth Century Ireland, p301