Hugh O’Neill and Nine Years War, 1594-1603

By John Dorney

In the early part of the 16th century the English Tudor monarchs had embarked on a project to bring all of Ireland for the first time under the control on their Crown.

By the 1590s, the Fitzgerald magnates of Munster had been smashed in the Desmond Rebellions. South Leinster was extensively garrisoned by English troops and in the west ruthless commanders named Drury and Malby enforced a pacification settlement known as ‘composition’ on the local lords.

There still remained one province of Ireland still unoccupied by English garrisons and out of the control of Lord Deputy Fitzwilliam in Dublin – Ulster.

It was in the northern province that the final, most destructive and most decisive war between the Gaelic lords and the encroaching English state would be fought; the Nine Years War.

A New ‘Prince of Ulster’

Hugh O’Neill, the son of the murdered Lord, Fear Dorcha O’Neill, educated in the Pale and reinstated in Gaelic Ulster by the English, would cast a long shadow over the future of the province. His own story so dominates that of Ulster and of Ireland in the late 16th century that it is worth looking at in detail.

The irony of Hugh O’Neill’s early life is that it looked as if his career would be tied to success of English government in Ireland. His father, who was held both the Irish title of O’Neill and the English one of ‘Earl of Tyrone’ was killed and his sons banished from Ulster as a child by his rival Shane O’Neill.

The Nine Years War was to a large degree the collision of the ambitions of Hugh O’Neill, Earl of Tyrone and of the advancing English state in Ireland.

Hugh O’Neill was fostered to a Pale family named the Hovendans. Hugh was supposed to be a model of English reform in Ireland. Like several other Gaelic noblemen of his generation, he had been brought up as an English gentleman and was supposed to bring “civility” with him into Ulster. Certainly, Hugh was capable of operating in the world of the English aristocrat. He attended parliament in Dublin and Court in London and cultivated powerful allies there, both Irish and English, such as the Earls of Ormonde and Leicester.

In 1587, he persuaded Elizabeth I to make him Earl of Tyrone, the English title his father had held. In the 1570s and again in the 1580s he fought with the English against Irish insurgents in Ulster and Munster, where Grey remarked he was, “the first Irish lord to shed blood”.[1]

But if the English were under the impression they had in Hugh O’Neill a man who would faithfully do their bidding, they were greatly mistaken. Hugh, as his actions would make clear, was as attached to autonomy and independent military power as any of his ancestors had been, and more shrewd, innovative and ruthless than any of them.

The real signifier of power in Ulster was not the legal title of Earl of Tyrone, but the position of The O’Neill, still held in the 1580s by the ageing Turlough Lineach. This title gave its holder the right to the obedience of all the O’Neills and their dependents in central Ulster. Turlough Lineach was now an old man and could not on go on forever.

Internecine fighting soon broke out among those O’Neills who wanted to succeed him. The position of tanaiste (second in command and probable successor) was contested by Hugh and the MacShane O’Neills, sons of Shane O’Neill – the late, self proclaimed, Prince of Ulster. The MacShanes name gave them greater prestige than Hugh, and they were the preferred choice of Turlough Lineach. However, their weakness was their lack of allies. The neighbouring clans hated them for the cruelties of their father Shane and had no desire to have one of them as an overlord. Further afield, the MacShane’s dynastic allies, the Fitzgeralds, had been annihilated in the Munster rebellion and could be of no help to them.

Hugh O’Neill, while he had less support within Tir Eoin, made intelligent use of his neighbours’ hatred of the MacShanes by making alliances through marriage with the most powerful of those neighbours. The most important ties he forged were with the O’Donnells of Tir Connell (modern Donegal), in particular a young pretender called Aodh Rua – Red Hugh, and the MacGuires of Fermanagh. From Red Hugh O’Donnell he got a supply of Scottish mercenaries – O’Donnell’s mother, Inion Dubh, was from the MacDonald clan of western Scotland – and a threat to Turlough Lineach’s seat at Strabane.

In return, he supported O’Donnells own claims to chiefdom. O’Neill was equally astute in his alliances outside Ulster. These included the Earl of Ormonde, the Earl of Leicester, the Earl of Argyle (in Scotland) and even Lord Deputy Fitzwilliam, whom he bribed throughout his tenure in office. As a result, Hugh received money and some soldiers from the English and a willingness to look the other way when he broke English law – as he regularly did.[2]

After much vicious bloodshed within Tir Eoin, Hugh finally forced Turlough Lineach to name him tanaiste in 1592. This made him effective ruler of the O’Neill lands, although Turlough Lineach did not die until 1595.

Hugh had cut his teeth in the utterly ruthless world of Gaelic Ulster’s high politics. The brutality which the now-mature Hugh was capable of included the killing of all of the MacShanes, one of whom, Niall Grabhalach, he was said to have hung with his bare hands over a hawthorn tree. [3]

To win out in internal succession disputes within the O’Neill lordship, Hugh made himself into a powerful warlord and made important alliances with neighbouring lords.

Within Duiche Ui Neill, Hugh made himself a kind of absolute monarch. Not satisfied with the customary tribute or rents from his fine, he extended his control directly over the territory. Within this domain, he tied the peasantry to the land, making them effectively serfs and guaranteeing his supply of labour. His revenue eventually translated into £80,000 a year. To put this into perspective, as late as the 1540s, the total tax revenue of the Tudor monarchy amounted to about £31,000.[4] While it had expanded since then, it was clear that O’Neill had made himself rich enough to rival the state.

To arm his military, he used his increased cashflow to buy muskets, ammunition and pikes from Scotland and England. Like his predecessor Shane, he made full use of his man-power by pressing all classes into military service. Ultimately, he was able to arm and feed over 8,000 men, unprecedented for a Gaelic lord. Far from introducing “civility” into the north he became the most powerful Gaelic warlord that the Tudors ever encountered in Ireland.[5]

It was inevitable that before long Hugh’s own ambition would collide with the advancing Elizabethan state. By 1587, the English were already suspicious enough to kidnap his ally, Red Hugh O’Donnell and hold him in Dublin Castle, thus temporarily delaying Hugh O’Neill’s victory in the internal power struggle in Tir Eoin.

In December 1591, after a number of failed attempts, O’Neill engineered O’Donnell’s escape (probably through bribery at high levels in Dublin) to the Wicklow mountains. There he found shelter with the Gabhal Raghnail O’Byrnes, whose chief, Fiach MacHugh, was among O’Neills web of allies. An O’Byrne search party found the fugitives near death and covered with snow near Glendalough.

The young O’Donnell lost his big toe to frostbite in the freezing December weather and his companion, Art MacShane O’Neill, died of exposure (although suspicious minds claimed he had been murdered by the O’Byrnes to eliminate him as a rival to Hugh O’Neill). The experience left Red Hugh with a bitter hatred towards the English, which was subsequently reinforced by his contact with Franciscan friars based in Derry. O’Donnell would henceforth be regarded as the most zealous of the Ulster lords. Not that he, or any of the northern lords, needed a personal reason to fear the English state. Events to the south of them provided much more pressing reasons. [6]

Composition

By the early 1590’s, northern Connacht and the southern rim of Ulster was engulfed by Lord Deputy Fitzwilliam’s “reforming” agents who applied the “composition” formula that had been hammered out in Munster and southern Connacht.

There was a short but bloody war in the Mac William Burke (northern Connacht) country, in 1588, when over a thousand Scottish gallowglass were imported by the Burkes to prevent the introduction of an English sheriff. All of them died in a murderous battle with Bingham, the President of Connacht at Ardnaree.[7] Having pacified Connacht, Fitzwilliam prepared to move on to Ulster.

War was triggered when it was mooted that Ulster would be governed by a provincial president – probably Henry Bagenel, an English colonist, English garrisons introduced and the existing Gaelic lordships broken up.

It was envisaged that Ulster would be governed by a provincial president – probably Henry Bagenel, an English colonist settled in Newry. The first subjects of the composition experiment in Ulster were in Longford, Cavan and Monaghan. In 1591, Fitzwilliam broke up the MacMahon lordship in Monaghan when the Lord (another Hugh) resisted the imposition of an English Sheriff. Hugh MacMahon was hanged and his lordship divided eight ways between his fine.

These were not to be independent political players, but simple landlords on the Queen’s land. Moreover, the freeholders (gradh fheine or free-men in Gaelic terms) were granted property rights to their land. They would pay rent to their local lord and to the Queen (2.5d and 1.5d respectively) but the lords would not have political or legal control over them. [8]

Similar solutions were applied in Longford and Breifne (Cavan) to the O’Rourke and O’Reilly lords respectively. Hugh O’Neill must have looked at these developments with horror. Firstly, the introduction of a sheriff would end his control over Tir Eoin that he had spent the better part of two decades fighting for. Secondly, it would reduce his property strictly to his own demesne, when he was trying to extend it to the land held by his fine. Thirdly, by giving legal status to the free-holders it would completely eliminate all of his personal political power by ending his ability to muster and maintain an army.

What was more, the MacMahon and O’Rourke chiefs had actually been hanged after their lordship was “reformed” and O’Reilly had been driven into exile. It was the threat that this settlement would be extended into his dominion that brought Hugh O’Neill into direct conflict with the English authorities. To the more devout, such as Red Hugh O’Donnell, English authority was not only the eclipse of his power, but also the eclipse of the One True Faith by heresy. The ensuing conflict, known to history as the Nine Years War, shook English rule in Ireland to its very foundations but ended with the final victory of the Tudor state over the old Gaelic order.

By 1592, the year of the two Hugh’s victories in their respective succession conflicts, O’Neill’s alliances had hardened into a confederation of the northern Gaelic chiefs. Even more significantly, since 1591 O’Donnell had been communicating (at O’Neill’s request) with Phillip II of Spain for military aid against the English heretics. His Most Catholic Majesty duly supplied them with arms, money and military advisors.

This was not merely a romantic gesture in support of fellow Catholics but a hard-headed strategic policy on the Spaniard’s part. The minutes of a meeting of Spanish Council of State records the benefits of helping O’Neill and O’Donnell, namely to tie down English troops which could be used against Spain in the Netherlands. Better yet, if Ireland was gained for Spain, it would increase the prestige of the Spanish monarchy, and give the Spanish a say in the choice of the next English monarch.[9]

In 1592, Red Hugh drove a Captain Willis (Sheriff of Tir Connell) out of Tir Connell – he having been more of a freebooter than a lawman in any case. In 1593, Maguire and O’Donnell combined to resist Willis’ introduction as Sheriff into Maguire’s Fermanagh and began attacking the English outposts along the southern edge of Ulster.

A negotiated settlement was still possible though. As yet, O’Neill stood aloof from the rebellion, although he was directing proceedings, hoping as a compromise to be named as Lord President of Ulster himself. Elizabeth I, though, had correctly perceived that O’Neill had no intention of being a civilised English landlord. Rather, his ambition was to usurp her sovereign power and be, “a Prince of Ulster”.

For this reason she refused to grant O’Neill provincial presidency or any other delegation of power which would have given him authority to govern Ulster on the crown’s behalf. She also had scathing words for his ingratitude, he, as far as she was concerned, having been raised into his position by English benevolence. [10]

O’Neill’s treachery was seen by many in London as a personal betrayal. For Hugh however, not to stand up to the English encroachment onto Tir Eoin would probably have been more costly than going along with it. If he had not defended his territory, as The O’Neill was required to do, another of his derbh fhine could have won the support of the O’Neill swordsmen and ousted and killed him.

For whatever combination of reasons, in 1595 Hugh O’Neill joined his confederates in open rebellion by attacking the English fort on the Blackwater river. It was also in this year that Turlough Lineach O’Neill died, so that Hugh was inaugurated The O’Neill at the traditional O’Neill inauguration site at Tullaghoe. It was a formal rejection of English authority. As one contemporary put it, “Tyrone [Hugh’s English title] was a traitor, but O’Neill none”.[11]

A War for Ireland

O’Neill was a politician of great shrewdness. He was anything but a consistent fighter for the Gaels or for Catholicism, in fact he had attended Protestant services up to 1594. In the early years of the war, he wanted a modest, negotiated settlement with the English. But by assuming the role of a Gaelic and Catholic crusader against the English Protestants, he was able to rally disaffected chiefs and lords throughout Ireland to his rebellion.

Moreover, the better things went for the rebels, the more ambitious O’Neill got. In his minimum demands, he wanted freedom of the Catholic religion and all public positions in Ireland to be filled by Irishmen. But later, he came to be fighting for an independent Ireland under Spanish suzerainty. In proclamations issued around Ireland he turned the language of the conquest on its head, saying he fighting for,

“the delivery of our country [from] infinite murders, wicked and detestable policies by which the kingdom was hitherto governed, nourished in obscurity and ignorance, maintained in barbarity and incivility and consequently of infinite evils which are too lamentable to be rehearsed”.[12]

In O’Neill’s proclamations, contrary to what English discourse had long maintained, it was the English, not the Irish who were the ignorant, murderous barbarians!

Hugh O’Neill initially went to war for a negotiated settlement but as the war went on, he declared he was fighting for Irish self government and the Catholic religion.

The above passage was written for the consumption of the Palesmen, appealing to their sense that the English government was infringing their constitutional and religious liberties by forcing them to pay extra-parliamentary taxes, quarter soldiers and denying them freedom to practise Catholicism.

This traditionally loyalist community generally maintained their political loyalty to the English Crown, despite their discontent. Their loyalty however was shaky and was put under severe pressure during the course of the war. English soldiers were required by decree to be housed by the townsmen of Dublin and they spread disease and forced up the price of food.

The wounded lay in stalls in the streets, in the absence of a proper hospital. In 1597, the English powder store in Winetavern street exploded, accidentally killing nearly 200 Dubliners. The O’Byrnes raided within two miles of the city, at one stage burning the townland of Crumlin, while the Ulster forces looted the north of the Pale repeatedly.[13]

The importance of O’Neill’s proclamations lay in their idea that Ireland should become a state to which its own elite would pledge their first loyalty. This was a huge innovation for a previously fragmented society. The longer the war went on, the more radical the rebels became and the more it became a self-declared Holy war.

In 1600, O’Neill wrote to the Gaelic lords of Munster, announcing his imminent arrival into the province, “I would come to learn the intentions of all the gentlemen of Munster regarding the great questions of the nation’s liberty and of religion”.[14] By 1601, O’Neill wrote to Florence McCarthy, his ally in south Munster, hoping “that you will do a stout and hopeful service against the pagan beast… our army is to come into Munster and do the will of God”.[15]

But despite their separatist and religious rhetoric, O’Neill and his allies were still traditional Gaelic lords and their objectives were the same as ever; to keep their own personal power and that of their clans intact. Many of them had concluded that the only way to do this was to get rid of the English.

The division between those natives who went into rebellion and those who did not was not in the final analysis cultural, or ethnic or even religious, but between those who could forsee a place for themselves in the new order and those who could not. Lord Barry Mór of Cork, for instance, whose father was imprisoned for life for his part in the Desmond rebellions, rejected O’Neill’s exhortations because he was firmly ensconced in his lands and had secured legal charter to them. He dismissed religious arguments on the grounds that he had never been troubled in the exercise of his religion.[16]

The greater part of the Irish elite flirted with both sides during the war, wanting to be on the winning side, but large numbers of them clearly preferred a future that would be determined by themselves rather than the English.

O’Neill’s years of Triumph

From the outset, O’Neill’s alliances made the rebellion felt far beyond Ulster. Dublin Castle soon realised that they had a nation-wide insurrection on their hands. Indeed, the first English reaction to O’Neills rebellion was to march on Wicklow to try and secure the Pale from Fiach MacHugh O’Byrne, who was once again attacking English garrisons and settlements. Equally importantly, O’Neill had learnt the military lessons of the Desmond rebellion. It was not enough to do as Shane O’Neill or the Fitzgeralds had done and use guerrilla tactics, thus exposing your own countryside to destruction as Munster had been during the Desmond rebellions.

From the outset, O’Neill’s alliances made the rebellion felt far beyond Ulster

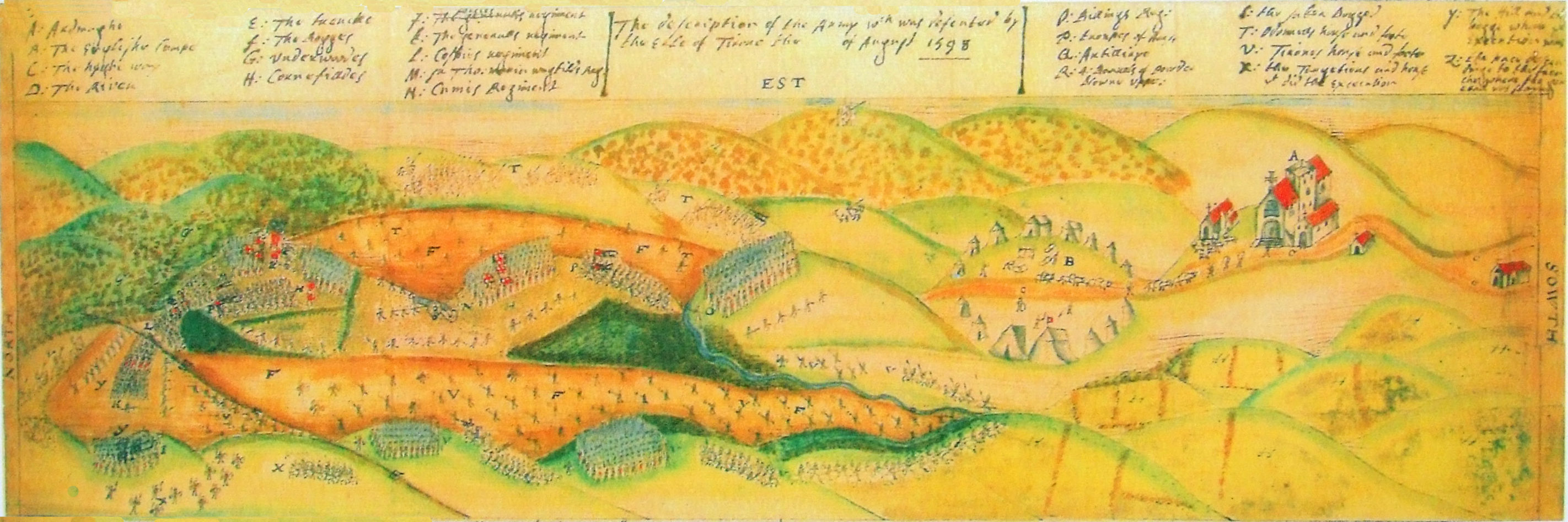

Ulster was to be defended at what was then the only points of access for a large army, that is in south Armagh and northern Sligo (the other routes into Ulster were covered by bog and woodland). When, after abortive negotiations in 1596, English armies tried to break into the province, they were met with thousands of musketeers in prepared positions, as well as the traditional Gaelic gallowglass, kerne and horsemen. Successive English offensives were driven back at Clontibret and Yellow Ford. At this last battle in 1598, between 800 and 2,000 English troops were killed, along with their commander Henry Bagenell, having been ambushed on the march to Armagh. [17]

The victory prompted rebellions all over Ireland, assisted by mobile contingents from Ulster. O’Donnell, imposed a sympathetic chief on the MacWilliam Burkes of Mayo and, with the aid of Scottish mercenaries and midlands lords such as Nugent of Westmeath, massacred the nascent English settlement in Connacht. Hugh O’Neill appointed James Fitzthomas Fitzgerald (a nephew of the late Earl Gerald) as the new Earl of Desmond (referred to by his detractors as the sugan or “straw-rope” earl) and Florence MacCarthy as the MacCarthy Mór.

The disaffected in Munster, and they were many, rallied to them. As many as 9,000 men came out in rebellion. In addition, O’Neill dispatched over 2,000 men from Ulster to the south, partly to aid the rebels, but also to take supplies he would need to sustain his troops throughout the winter. The Munster plantation was utterly destroyed, the colonists, among them Edmund Spenser and Walter Raleigh, fled for their lives.

The Annals tell us, “ in the course of seventeen days [the rebels] left not, within the length or breadth of [Munster] which the Saxons had well cultivated and filled with habitations and various wealth, a single son of a Saxon whom they did not either kill or expel”.[18]

Earl Ormonde, who stayed loyal, complained that most of the colonists had “shamefully” fled rather than try to defend their lands. Only a handful of native lords (Barry, Clanrickarde, O’Brien) remained consistently loyal to the crown and even these found their kinsmen and followers defecting in droves to the rebels. MacCarthy Reagh was able to mobilise only 80 of his closest kinsmen for the English, the rest having sided with the rebels.[19]

In Wicklow, Fiach MacHugh O’Byrne’s long career of raiding was finally brought to a close when his mountain stronghold at Ballinacor, Glenmalure, was burned and his territory garrisoned. He himself was tracked down and beheaded in a cave in 1597. However, his son Phelim Mac Fiach carried on guerrilla attacks from the mountains of south Wicklow.

Hugh O’Neill, unable to take walled towns, made repeated overtures to the Palesmen to join his rebellion, appealing to their Catholicism and to their alienation from the Lord Deputies and the New English. For the most part, however, the Gaill remained hostile to their hereditary enemies. Nevertheless, the English state in Ireland had never looked more shaky.

It is often assumed in hindsight that the Nine Years War represents a doomed struggle of a backward people against the might of the English state. But it was not so. Elizabethan England did not have a large standing army, nor was the state strong enough to extract enough taxation to pay for long wars – despite it being among the richest countries in Europe. Moreover, it was already involved in a war in the Spanish Netherlands. As it was, the war in Ireland (which cost over £2 million) came very close to bankrupting the English exchequer by its close in 1603.[20]

Had Spanish troops landed in force in 1598, it would have been next to impossible for the English to hold or re-conquer the island. Luckily for the English, they did not. Nevertheless, cooped up in the Pale and the walled towns, the future for the English must have seemed very bleak indeed.

In 1599, the Earl of Essex arrived in Ireland with over 17,000 English reinforcements, a huge army for the time and place. He dispersed them in garrisons all over the country to stamp out rebellion in Muster and Leinster, but was unable to meet the Ulster forces in battle, instead signing a humiliating truce with O’Neill. Those expeditions he did organise were disastrous. A sortie into the Wicklow mountains was mauled by Phelim MacFiach O’Byrne, as was a force crossing the Curlew mountains in Sligo by O’Donnell.

Thousands of his troops, shut up in unsanitary garrisons, died of diseases such as typhoid and dysentery, to which the English in Ireland seemed to be particularly vulnerable. As a last resort, Essex challenged O’Neill to single combat to settle the war. O’Neill, icily pragmatic as ever, did not respond. Essex was recalled to England in disgrace in 1600, where he was executed after attempting a court putsch. He was succeeded in Ireland by Lord Mountjoy, who proved to be far more able commander. Tough and ruthless veterans named George Carew, and Arthur Chichester were given commands in Munster and Ulster respectively.[21]

The tide turns

Carew managed to more or less quash the rebellion in Munster by mid 1601 by a mixture of conciliation and military force. By the summer of 1601 he had retaken most of the principle castles in Munster and scattered the rebel forces.

Fitzthomas and Florence MacCarthy were arrested and sent to the Tower of London, where both of them eventually died in captivity. Most of the rest of the local lords submitted once O’Neills mercenaries had been expelled from the province.

The main war however, was in the north. Mountjoy managed to penetrate the interior of Ulster by sea-borne landings at Derry under Henry Dowcra and Carrigfergus under Arthur Chichester, while trying himself to break through overland through south-east Ulster.

English forces used the brutal tactics of the Desmond wars, devastating the Ulster countryside and killing the civilian population at random. Their military assumption was that without crops and people, the rebels could neither feed themselves nor raise new fighters.

Dowcra and Chichester (the former helped by Niall Garbh O’Donnell, a rival of Red Hugh) used the brutal tactics of the Desmond wars, devastating the countryside and killing the civilian population at random. Their military assumption was that without crops and people, the rebels could neither feed themselves nor raise new fighters. Chichester reported of one such raid;

“We have killed, burnt and spoiled …within four miles of Dungannon…we have killed above 100 people of all sorts, besides such as were burnt, how many I know not. We spare none of what quality or sex soever, and it hath bred much terror in the people…The last service was upon Patrick O’Quinn, whose house and town was burnt, wife, son children and people slain”[22].

This report is typical of English tactics all over the country, which deliberately targeted the civilian population. This attrition quickly began to bite, and particularly so after Chichester began launching raids across Lough Neagh into the heart of Tir Eoin. It also meant that the Ulster chiefs were tied down in Ulster to defend their own territories. Although O’Neill managed to repulse another land offensive by Mountjoy at Moyry Pass near Newry in 1600, his position was becoming desperate.

‘Immense and countless was the loss in that place’ – The Battle of Kinsale and after

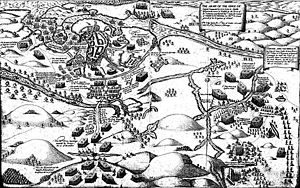

In 1601, the long-promised Spanish expedition finally arrived in the form of 3,500 soldiers at Kinsale, Cork, virtually the southern tip of Ireland.

English commander Mountjoy immediately besieged them with 7,000 men. O’Neill, O’Donnell and their allies marched their armies south in freezing December weather to sandwich Mountjoy, whose men were starving and wracked by disease, between them and the Spaniards.

At the battle of Kinsale, a Spanish expedition to aid O’Neill and O’Donnell was defeated, ending their hopes of winning the war.

Kinsale has become an iconic battle in Irish history, and rightly so. It did not end the war and it did not by itself destroy Gaelic culture or the Gaelic aristocracy, but it decide the future outcome of the war and therefore of the English presence in Ireland. The point is, after Kinsale, the chance of an Irish victory had passed, and the question was not whether Ireland would be English, Spanish, or independent, but what terms the rebels could hold out for.

For such a historical turning point it was a rather confused and inconclusive battle. The Irish advanced in a driving thunderstorm, but their attack stumbled on the advancing English cavalry, and part of the Irish infantry panicked and fled. They were then pursued for miles by the English horse who killed several hundred of them. The remainder of the Irish withdrew as did the Spaniards, who surrendered in an orderly fashion days later and were allowed to return to Spain.[23]

The Irish, amid bitter recriminations among their leaders for the defeat, headed home to Ulster to defend their own lands. The Ulstermen lost many more men in the retreat through freezing and flooded country than they had at the actual battle of Kinsale. Eoghan O’Sullivan Beare held out in his territory in Kerry for several more months before fleeing for Ulster himself with his kinsmen and followers.

Hugh O’Donnell left for Spain, where he died in 1602, pleading in vain for another Spanish landing. He left his brother Rory to defend Tir Connell. Both he and Hugh O’Neill were reduced to guerrilla tactics, fighting in small bands, as Mountjoy, Dowcra, Chichester and Niall Garbh O’Donnell swept the country, burning and killing as they went. Mountjoy smashed the O’Neill’s inauguration stone at Tullaghogue, symbolically destroying an order that had lasted for hundreds if not thousands of years.

Famine soon hit Ulster as a result of the English scorched earth strategy. Chichester’s forces found that the locals were reduced to cannibalism, in one instance coming upon five children eating a dead woman. Fynes Morrison, Mountjoy’s secretary, recorded that;

“No spectacle was more frequent in towns and ditches and especially in the wasted countries, than to see multitudes of these poor people dead with their mouths all coloured green by eating nettles”.[24]

In the midst of this horror, it is not surprising that O’Neill’s uirithe or sub-lords (O’Hagan, O’Quinn, MacCann) began to surrender, the most important of whom was Donal O’Cahan. Rory O’Donnell surrendered on terms at the end of 1602. Nevertheless, despite a large reward being put on his head, and despite being driven to the woods with only his creaghts (cattle herders) and a small armed force, the English found it impossible to track down O’Neill. With a secure base in the large and dense forests of Tir Eoin, O’Neill held out until 30 March 1603, when he surrendered on good terms to Mountjoy. Had he known that Elizabeth I had died a week before, he would probably have struck an even harder bargain. As it was, he wept with frustration on hearing the news.[25]

The End of the War

The really surprising thing about the end of the Nine Years War, considering the enormous cost it took the English to win it, and the outright treason involved – conspiring to give the kingdom of Ireland to a foreign power – is the generosity of the terms which the rebels got on surrendering. At the Treaty of Mellifont, O’Neill, O’Donnell and the other surviving Ulster chiefs received full pardons and the return of their estates.

At the Treaty of Mellifont in 1603, O’Neill, O’Donnell and the other surviving Ulster chiefs received full pardons and the return of their estates.

The stipulations were that they abandon their Irish titles (thus becoming Earls of Tyrone and Tyrconnell rather than O’Neill and O’Donnell), abandon the Brehon laws, private armies, their control over their uirithe and swear loyalty only to the Crown of England. O’Neill was even given authority over O’Cahan, whom he never forgave for his desertion during the war. In 1604, Mountjoy declared an amnesty for rebels all over the country.

In the short term, it was difficult to work out what all the bloodshed had been for, as disgusted New Englishmen like Arthur Chichester pointed out. The simple truth was that the Crown was broke, it could not afford to carry on the war in Ireland any longer. In the long term, though, the war marked not only the end of the century but the end of the Gaelic order. With the last independent military powers conquered, the true confiscation, Anglicisation and Protestantisation of Ireland could begin.[26]

Counting the Cost

In human terms, the Nine Years War was nothing short of a catastrophe. Most of the country had been fought over at some stage, its land ruined, civilians of all sides killed and looted.

Ulster and north Connacht was utterly devastated, burned and plundered, the people starved, killed and driven to the hills and woods for refuge.

For years afterwards, Ulster was still ridden with “wood-kerne” or bandits who had fought in or been displaced by the war. Munster had had its third war in 20 years, and its young English community had fled. The Pale had been ruined by the quartering of thousands of English soldiers there and the raids of the rebels

How many died between 1594 and 1603? Irish sources claimed that as many as 60,000 people had died in the Ulster famine of 1602-3 alone.[27] Even if this is an exaggeration, counting the unknown number killed in battle or massacred, an Irish death toll of over 100,000 is not excessive. Considering that the population of Ireland at the time was less than 1 million, this means that around one in ten people in Ireland may have died as a result of the war. In addition, thousands of Scottish Gaels fought in the war as mercenaries (mainly, though not only, on the rebel side), several thousand of whom were killed.

For the common people of the west of England and Wales, the war was also a tragedy, for it was their sons and husbands who were, mostly unwillingly, conscripted to fight in Ireland. At least 30,000 English soldiers died in Ireland in the Nine Years War, mainly from disease. O’Neill himself claimed 70,000, “in action and otherwise”.[28] The morale of the English soldiers in Ireland was in general very low. Many thousands deserted and sold their weapons to the Irish. A proverb noted at the time in Chester went, “better to hang at home [for evading conscription] than to die like a dog in Ireland”.[29] When O’Neill (or Tyrone as he then was) travelled through Wales with Mountjoy on his way to the court of the new King James I, he was pelted with stones and mud by the relatives of dead soldiers.[30]

So the total death toll for the war may have been in the region of 150,000 people, if not more. Perhaps the only winners of the Nine Years War were the Spaniards, who, for a relatively small investment, tied down thousands of English troops, and bled their treasury dry. Not only that, but when the war was over, they began to reap a rich harvest of exiled Gaelic Irish nobles and their clan followers who gave over 80,000 men to the Spanish Army in the first half of the 17th century.

Two highly significant events rounded off the Tudor conquest (which was actually finished under the James Stuart King of Scotland who also assumed the English throne in 1603). The first took place in 1603, not long after O’Neill’s surrender at Mellifont.

The Old English towns of Munster, including Waterford, Cork and Limerick rebelled, expelling Protestant ministers, imprisoning English officials, seizing the municipal arsenals and demanding freedom of worship for Catholics. They refused to admit Mountjoy’s army when he marched south, citing their ancient charters from 12th century. Mountjoy retorted that he would, “cut King John his charter with King James his sword” and arrested the ringleaders, thus ending the revolt.

The effect of the episode though, was to show just how estranged the Old English had become from the Protestant state. It was an ominous sign for the coming century. [31]

The second defining event of the decade happened in 1607, when O’Neill, O’Donnell and many other Ulster chiefs left for Spain, in what is known as the Flight of the Earls. At first sight it is puzzling why they abandoned such a favourable settlement as they got at the end of the Nine Years War.

Hugh O’Neill and the other surviving Ulster lords fled Ireland in 1607, paving the way for the Plantation of Ulster.

After all, they were returned their lands and given responsible positions in the new order. However, after Mountjoy, with whom O’Neill had a good relationship, resigned as Lord Deputy, he was replaced by Arthur Chichester, who had a much less conciliatory attitude. Chichester harassed O’Neill, forced him to attend Protestant services, accused him of treasonable plotting with Spain, and may even have been trying to assassinate him (O’Neill certainly believed that he was). O’Neill referred to Chichester’s policy as “destruction by peace”.

Recent research done in continental archives shows that the Flight of the Earls was really a “planned tactical retreat” to enlist more Spanish or Catholic help and return to remove the English from Ireland altogether. This proved to be a terrible mistake on their part. O’Neill was told politely that Spain could not help the Irish Catholics right now, as Phillip III was hoping for peace with the new British monarch. O’Neill was not even allowed to enter Spain and died in exile in Rome in 1616. [32]

In the absence of their Earls, the Gaelic land of central and west Ulster was confiscated en masse and planted with thousands of Protestant English and lowland Scots. The “loyal Irish” (that is those who had fought with the English in the war) received a quarter of the worst land. Two of these, Cahir O’Doherty and Niall Garbh O’Donnell, launched a futile rebellion in protest, which succeeded only in getting themselves hanged.

The new settlements were banned from taking native tenants or employing them as labourers – thus banishing the Gaelic Irish to the worst land in the hills and bogs. In east Ulster, a private plantation occurred on the lands of the Clandeboye O’Neills, which had been almost depopulated during the war. Only the MacDonnells in Antrim survived relatively intact, having good contacts with the new Scottish monarch, James I.

Six thousand Gaelic former soldiers were sent abroad into the Swedish service, although they eventually defected to Catholic Spain. They were followed by thousands of others, whose clan leaders were allowed to return to recruit them – so anxious were the English to get them out of Ireland.[33]

Gaelic Ulster had been changed forever. In Munster, the plantation of the 1580’s was reconstituted, with many of the original settlers returning. The English and Protestant interest in Ireland now had a secure foothold. Nevertheless, a great many of the native Irish elite survived the re-conquest on their own territory, albeit under state military and legal control. It was the coming century that would finally displace them.

References

[1] Hiram Morgan, Tyrone’s Rebellion, The Outbreak of the Nine Years War (1993), p94

[2] Colm Lennon, Sixteenth Century Ireland the Incomplete Conquest, (1994) p283-286

[3] Sean Connolly, Contested Island, Ireland 1460-1630 (2007) p229

[4] Roger Schofield, Taxation under the early Tudors, 1485-1547, p70

[5] Nicholas Canny, Hugh O’Neill, Earl of Tyrone and the Changing Face of Gaelic Ulster, Photocopy 9262 UCD Library.

[6] Lennon p289

[7] Lennon p254-255

[8] Stephen Ellis, Ireland in the Age of the Tudors (1998), p298

[9] Constantia Maxwell, Irish History From Contemporary Sources (1509 – 1610), George Allen & Unwin Ltd., London 1923, p674

[10] Morgan, Tyrone’s Rebellion p177-178

[11] Morgan, Tyrone’s Rebellion p189,

[12]Hiram Morgan, Hugh O’Neill and the Nine Years War in Tudor Ireland, The Cambridge Historical Journal, 1993, 21-27

[13] Lennon, p295

[14] McCarthy Daniel The Letter Book of Florence MacCarthy Reagh, Tanist of Carberry, p227

[15] O’Neill to Florence MacCarthy, 27 January 1601, (Cal. S.P Ire 1601-1603, p.392)

[16] Calender of State Papers Ireland 1599-1600, p493-494

[17] Lennon p296

[18] Annals of the Four Masters

[19] Ormonde to Queen Elizabeth, October 1598, McCarthy, Letter Book p.177

[20] Lennon p302

[21] Lennon p297-298

[22] Calendar of State Papers, Ireland, Vol CCVII, pt 2, p91

[23] Connolly p 252, Lennon p300-301

[24] Connolly p254

[25] Lennon p301

[26] Nicholas Canny, Making Ireland British, 1580-1650, p166-169

[27] Michilene Kearney Walsh, Destruction By Peace, p205

[28] John McCavitt, The Flight of the Earls (2002), p51

[29] John McCavitt, The Flight of the Earls, p8

[30] Ibid. p54

[31] McCavitt, p53

[32] McCavitt, p89-91

[33] Padraig Lenihan, Consolidating Conquest, Ireland 1603-1727, p48