What to do about the past?

John Dorney on the past, present and future of conflict resolution in Ireland.

Some of us, upon some months ago, hearing of the agenda of recent peace negotiations in Northern Ireland – flags, parades and what to do about the past – scoffed a little along the lines of, ‘ they have little to be worried about these days’.

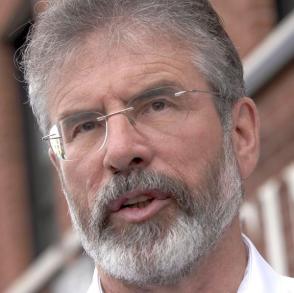

However, the recent arrest of Sinn Fein leader Gerry Adams and his detention and questioning for four days about the abduction and murder of Jean McConville in 1972 has brought the issue ‘what to do about the past’ into sharp focus. It turns out that the Police Service of Northern Ireland (PSNI) is still actively pursuing prosecutions from the thirty year low intensity conflict we still call ‘The Troubles’. What indeed is to be done about the past, or to be more precise whether those who committed violent acts but were never prosecuted can still go to prison, really is a live issue.

There appear to be many anomalies in how this question is being approached within Northern Ireland. Only a few months ago it was revealed, to the fury of unionists, that the London government was giving assurances to former IRA members that they were no longer being actively sought for offences committed prior to 1998 and the signing of the Good Friday Agreement. Furthermore, under the terms of that agreement, all paramilitary prisoners (republican and loyalist) whose political organs had signed up to the deal were freed, regardless of how long they had served of their sentence.

To make Adams’ situation stranger still, it has been made clear that although the identities of British soldiers who shot and killed civilians in Derry on Bloody Sunday in 1972 are known, they will not be prosecuted. In November of 2013, a BBC documentary retraced the steps of an undercover British Army unit charged with assassinating republican paramilitaries in the early 1970s, who were responsible for at least ten killings of unarmed civilians[1]. No calls were made by Police to the journalists in question to force them to hand over their interviews, nor to reveal the identity of their interviewees.

So it appears that Gerry Adams and Ivor Bell (the latter charged with the McConville killing) both of whom were reputed to be senior figures in the Belfast Brigade of the Provisional IRA in the early 1970s, have been singled out for special treatment. Why this is and who is behind it this article does not know and cannot speculate. Suffice to say that the killing of Jean McConville; a mother of ten, shot and secretly buried by the IRA as an alleged informer; has a particularly high emotional resonance and that both Bell and especially Adams were and in the latter case still is, an extremely senior member of the republican movement.

There is a wider issue here, however and one that has had to be faced many times before in Irish history. When is a war, often an undeclared, unrecognised insurgency, really over? Can a veil be drawn over what was done in times of ‘war’? Does peace mean, as in South Africa truth and reconciliation, where the perpetrators of violence admit what they did but face no punishment? Or does peace rather require what was called in post-Franco Spain, ‘a pact of forgetting’?

How to end an irregular war

As far back as 1641, the Catholic insurgents in the rebellion of that year sought as part of the terms with which they hoped to reach an agreement with Charles I, an ‘Act of Oblivion’ in which all acts committed in the uprising would be pardoned. (For the background to this episode see here).

In the 1650s the Cromwellians punished those they deemed had ‘murdered’ in the rebellion of 1641 but amnestied the regular Confederate Catholic soldiers after they had surrendered.

Later on in the 1650s, the remnants of the Confederate Catholic armies, now guerrilla bands, who had fought and lost against an English Parliamentarian re-conquest of Ireland, were faced with how to bring the conflict to an end without losing their lives and property to the victorious Cromwellians.

Interestingly, the forces of the English Parliament made a distinction between soldiers who fought in the regular Confederate armies, who once they surrendered before May 1652, could either leave Ireland to enter foreign service or go home, and the insurgents of 1641, especially those who had killed Protestant civilians. The latter were punished with death where caught. All Catholic landowners lost some land under the Cromwellian settlement but actual vengeance for ‘murders’ committed in 1641 was limited to several hundred hangings, which by the standards of other Parliamentarian actions in Ireland amounted to relative mildness.[2]

After the 1798 rebellion the British reaction was repression mixed with pragmatic use of amnesties.

This was simple pragmatism on the part of the Commonwealth regime. Executing tens or hundreds of thousands of former Confederate soldiers was simply not feasible. Moreover, the spirit of vengeance does not seem to have outlasted the Restoration of the monarchy in England in 1660.

If we skip forward in Irish history to 1798 and the aftermath of the defeated republican insurrection of that year, we find both severity and pragmatism in the British approach. The leaders of the uprising who were captured were sentenced to hang (notably Theobald Wolfe Tone who preferred instead to commit suicide in prison) and many more suffered transportation to Australia or exile for life in France or America. The Crown forces also committed many summary and revenge killings of ordinary insurgents after the fighting had died down.

However, an amnesty was also declared by the British government for rank and file United Irishmen; ‘notwithstanding the abhorrence which his Majesty justly entertains for the present unnatural rebellion raging in this country; yet wishing to exercise his Royal prerogative of mercy and by lenient means to bring back a sense of their duty to those deluded from their allegiance, holds forth a free pardon and oblivion for all past offences with such conditions as shall be deemed absolutely necessary for the public safety.’[3]

In short, although the amnesty contained the significant proviso that it was subject to ‘public safety’, the British approach was that once the fighting was over, there would be no further prosecution of ‘rebels’. The Crown forces never acknowledged of course the legitimacy of the republican insurgents, but they did accept, pragmatically, that different conditions pertained in peace than in war, whether the latter was recognised as such or not.

That said, in both of the early modern conflicts cited above the leaders of failed rebellions were either executed or exiled for life (or until in the case of the Cromwellians, their regime was ousted in England).

Ending the Irish revolutionary period

Perhaps though, these are spurious precedents from which to judge current events in Northern Ireland. The pre-industrial, pre-democratic world of the 17th and 18th centuries was very different from our own. Moreover the conflicts of 1641-52 and 1798 ended in clear victory for the English or British forces in Ireland, something that was not true of the Northern Ireland Troubles.

For both of these reasons perhaps more illuminating comparisons for the present day can be sought in the series of political and armed conflicts over Irish independence from 1912 to 1924 that for convenience sake we know call the Irish revolutionary period. How was this conflict (or conflicts) ended?

To take first of all the treatment of the insurgents after the Easter Rising of 1916. The British reaction to this defeated insurrection in many ways bears comparison with the repression of Irish rebellions in previous centuries. The leaders of the rebellion were executed or sentenced to long sentences of hard labour. The rank and file on the other hand were imprisoned but amnestied after a relatively short period – most, over 1,000, were home by the Christmas of 1916.

What was unusual about the reaction to the Rising was that even the most senior (and unrepentant) veterans of the rebellion, numbering about 200, were released and amnestied in the summer of 1917. This marks a real shift in British treatment of defeated Irish insurgents; an effort to make consensual politics work in Ireland and to refloat the compromise of Home Rule.

While The Rising retains its reputation as a relatively chivalrous affair, in reality it was no cleaner than any other military conflict. Leaving aside the excesses of the British military (who aside from inadvertently killing civilians through artillery bombardment had deliberately killed at least 15 civilians in one incident alone), the Volunteers had deliberately killed unarmed policemen and on occasion civilians who interfered with their barricades. Yet less than two years after their surrender in Dublin, all of them were again free and planning the next stage in the struggle.

Tactically of course the short imprisonment of most 1916 fighters proved a major miscalculation on the part of the British government. In the view of one policeman in Clare ‘the release of so many interned rebels instead of exciting gratitude appears to stimulate resentment. These men generally appear unsubdued by internment, and their release is by ignorant country folk regarded as proof that they were interned without any just cause and that the police who arrested them in pursuance of orders acted vindictively’[4].

The British government at first acted with great severity to the leaders and fighters of the 1916 insurrection in Dublin, but had released and amnestied all the surviving fighters of the Easter Rising by mid 1917.

In the next round of conflict from 1919-21 (conventionally called the Irish War of Independence), in which IRA guerrillas took on the state’s police and military, the British interned some 4,500 republican suspects and imprisoned some 1,500 more after trial, a total of over 6,000. The Truce of July 11 1921 that ended outright hostilities did not see the republican prisoners released, but it did see a commitment on the British side not to arrest or pursue IRA guerrillas for acts committed prior to the truce. Under the terms of the Anglo-Irish Treaty, signed in December 1921, all the republican prisoners were released in early 1922.

For the first time, the British state had not been victorious over a nationalist insurgency in Ireland. Although the British government preferred to view the establishment of the Irish Free State and Northern Ireland as the settling of the Irish Question by setting up two loyal dominions, in fact, in effect it left its enemies in power in the southern 26 counties. Loyalists marooned on the wrong side of the border lamented that there would now be no punishment for cowardly ‘murderers’ of the IRA. And indeed there was not.

High profile cases, that bear comparison with the McConville killing, such as the killing and secret burial of Mrs Lindsay – an aged loyalist who had given away an IRA ambush in County Cork and caused the death of a number of Volunteers – were never solved. There were of course, many more such cases on both sides, in a conflict in which 898 civilians were killed, at least 280 by the IRA and 380 by the British forces and another 236 by accident or unknown assailants. Forgoing retribution for these killings was the price of peace.[5]

This of course was not the end of the Irish Revolution, for it played out in what amounted to two civil wars in 1922-23. The first, an undeclared one, was effectively between north and south as IRA guerrillas tried to bring down the newly established Northern Ireland state. This episode, which raged with particular intensity in the first half of 1922 claimed around 500 lives, disproportionately of civilians (and disproportionately Catholics) in Belfast.

The second civil war, (the one which bears the name Irish Civil War) was fought for nine months in the Free State between pro and anti-Treaty republican factions over whether to accept the Anglo-Irish Treaty, did effectively end the Irish revolution. By its close the pro-Treaty Free State government had ground down the anti-Treaty IRA and held over 12,000 men and women prisoner. It had the added effect, for good measure of crippling any republican ambitions to overthrow Northern Ireland.

the Anglo_Irish Treaty effectively amnestied IRA guerrillas of 1919-21 and after the Civil War, the Free State declared a general amnesty in August 1923

The aftermath of this conflict in particular shows how ‘peace and reconciliation’ was achieved (or not) in 1920s Ireland. And here the results were highly ambiguous. The defeated republican prisoners in the Free State were released in dribs and drabs throughout 1924.

Terrible things had been done on both sides in the Civil War. Republicans had undertaken a determined and sometimes deadly arson campaign against the homes of Free State supporters as well as assassinating a number of pro-Treaty civilian supporters. Free State forces had judicially executed some 80 republicans and summarily executed over 100 more while prisoners or disarmed.[6] The Free State government often denied they had been in a war (as opposed to a situation of anarchy and armed crime) at all. The Civil War, moreover never properly ended. The anti-Treaty IRA dumped arms and went home but never surrendered or handed over their weapons.

And yet in August 1923 (with an Act of Indemnity for its own forces) and in late 1924 (with an act of General Amnesty for all prisoners) the Free State government enacted an amnesty for all acts committed in the Civil War.[7] There would in future be no prosecutions, nor any further official retribution for the horrors of 1922-23. This was in fact done as much to protect the government, many of whose actions had in fact been illegal, as to rehabilitate the anti-Treaty guerrillas but the fact remained that once the Civil War was over, it stayed over.

In Northern Ireland, the situation was somewhat muddier. Nevertheless, the Northern state began releasing its republican and (very few) loyalist prisoners in 1923. No amnesty was declared but as IRA men who had fled the six counties in 1922 began drifting back, many were quietly informed by the Royal Ulster Constabulary that they would no longer be pursued as long as they did not return to republican militancy. This did not stop some of them being interned during renewed IRA campaigns in the 1940s and 50s however.[8]

Dealing with memory

The controversy over Gerry Adams was sparked by a project by journalist Ed Moloney and republican activist turned historian Anthony McIntyre to collect statements for Boston College from veterans of the Northern Ireland conflict. It was agreed with the participants that their testimony would not be published until after their deaths. However the untimely deaths of two contributors, loyalist David Ervine and republican Brendan Hughes led to the publication by Moloney of a book – Voices from the Grave – based on Hughes’ and Ervine’s recollections. Included in Hughes testimony were allegations that Gerry Adams had been involved in the decision to kill Jean McConville in 1972.

The Bureau of Military History unlike the Boston College Tapes, was kept sealed until the last living survivor of the 1916-23 period was dead.

The Police Service of Northern Ireland then demanded that the tapes be handed over to them for the purposes of investigation and after a legal battle, they were.

This saga has a straightforward equivalent in the aftermath of the 1920s revolutionary period. The Irish Free State embarked in the 1940s and 50s on a much more extensive oral history project – the Bureau of Military History (BMH) – which collected over 1,500 statements from veterans (almost all nationalists or republicans) of the independence struggle. The key difference here is that the Bureau’s contents were not published until after the last veteran of the period had died. This was Dan Keating who passed away in 2006.

Though the decision to keep the BMH files locked away for half a century has been much criticised, with hindsight it may well have been wise and the Boston College project might have been well advised to follow suit. In his statement, for instance, IRA fighter Dan Breen details how his column in the Civil War abducted and killed and secretly buried two young Free State intelligence officers who were acting as ‘spies’.[9] Had this been published in his lifetime, how would the relatives of the dead have reacted to Breen – a sitting TD? Whether or not it was psychologically healthy for participants to bottle up (as almost all did) all the pain inflicted in the revolutionary years, politically it was indispensable.

Conclusion

This brings me to my final point. I have tried to point out in this article that Irish history is full of internal insurgencies and wars. After virtually all of them, amnesties were eventually declared. Whether one likes it or not, the same rules cannot apply to peacetime as to periods of armed conflict, when large elements of the citizenry confront each other. As a matter of practicality a line must be drawn under the conflict once it over. The most problematic aspect of the Adams case is that it opens the prospect of the imprisonment of hundreds or even thousands more people (in theory if not in practice).

Re-opening prosecutions risks re-opening old hostilities but silence about the past is not healthy either

On the other hand it can also be argued whether the veil of silence that for so long hung over the darker actions of the revolutionary years was a positive thing. Bear in mind in this connection that while the victims of the Northern Troubles have been painstakingly counted and named, we have only now got a rough idea of even how many died in Ireland between 1916 and 1923. It cannot have been healthy for southern Irish society that the widespread killing of informers in 1919-21 or the equally widespread torture and abuse of prisoners of the Free State was never openly confronted in any way.

This silence surely contributed to other silences in independent Ireland, such as that around the abuse of children in Church and state institutions or the remarkable secrecy of Irish cabinets until the present day.

In an ideal world, Northern Ireland would declare an amnesty from legal consequences for acts of political violence committed from 1969 to 1998 but would also force those – on all sides, not only one – who committed them to come clean and take responsibility for what they did.

References

[1] http://www.bbc.com/news/uk-24987465

[2]See John Cunningham, Conquest and Land in Ireland: The Transplantation to Connacht, 1649-1680, p25-26

[3] Sequel to Personal Narrative of the “Irish Rebellion” of 1798

By Charles Hamilton TeelingP191 online here.

[4]Michael Laffan, The Resurrection of Ireland, The Sinn Fein Part 1916-1923 p55

[5] Eunan O’Halpin, Counting Terror in, David Fitzpatrick (Ed.) Terror in Ireland 1916-1923, p154

[6]One such republican list records 77 ‘official murders’ and 105 ‘unofficial murders, Wolfe Tone Annual 1962.

[7]Breen Timothy Murphy, PHD Thesis, The government’s Execution Policy during the Irish Civil War, 1922-23, Maynooth, 2010.

[8]See for instance the experience of Tom Glennon IRA veteran who returned to Belfast in the 1930s, Kieran Glennon From Pogrom to Civil War, Tom Glennon and the Belfast IRA, p250-251.

[9]His statement is here p 182, He also discusses the execution for ‘spying’ of one Sgt McGrath of the Free State Army .