The Dead of the Belfast Pogrom – Counting the Cost of the Revolutionary Period, 1920-22

By Kieran Glennon

The “Belfast pogrom” was the term given to a period of intense political violence in that city which lasted from 1920 to 1922.

While it largely corresponded with the Irish War of Independence, it had a different chronology from events in the rest of Ireland.

The violence in Belfast also had an added dimension in that it was part of a reaction by unionism against the struggle for Irish independence. This article is the product of research carried out over a number of years to ascertain the number of deaths this caused.

Introduction

By the time violence erupted in Belfast in the summer of 1920, the War of Independence was already eighteen months old. Although the latter was brought to a close in the south with the signing of the Treaty in December 1921, the Belfast pogrom continued well into 1922 while at the same time, the northern IRA continued its War of Independence by mounting attacks against the Unionist government of Northern Ireland until the summer of that year.

This article is an attempt to count and analyse the nearly 500 deaths in Belfast due to political violence in 1920-22.

The use of the term “pogrom” to describe the events of that period in Belfast is disputed. It is almost never used by unionists. Some historians have challenged its use, most notably Robert Lynch, who said that what happened in Belfast “lacked many of the key characteristics that are inherent in the term ‘pogrom.’”[1]

This author acknowledges that what happened in Belfast does not strictly conform to dictionary definitions of the word “pogrom” as that term began to be understood in the early twentieth century, most notably in the wake of pogroms directed at Jews in eastern Europe. However, the term was widely used at the time by nationalists, as those against whom the vast majority of the violence in Belfast was directed felt that what was being done to them corresponded with what they understood a pogrom to entail. Respecting that lived experience, I use the word.

Nor is there agreement about the impact of the pogrom in terms of the number of fatalities involved.

The starting point for most historians is a list of 455 people – 267 Catholic, 185 Protestant and 3 “unascertained” – who were killed in Belfast from July 1920 to June 1922; this list was contained in the pamphlet Facts and Figures of the Belfast Pogrom, written in 1922 under the pseudonym G.B. Kenna by a Belfast priest, Fr John Hassan. For reasons that will be explored below, Hassan’s list is incomplete and in some respects, inaccurate.[2]

His list has since been added to, with different authors arriving at different totals for the number of deaths. Belfast local historian Joe Baker had a more extensive list of 469 deaths. Robert Lynch had a total of 464, while Peter Hart had two different totals, 409 and 470; neither of these writers identified the fatalities individually by name. Using accounts in contemporary Belfast newspapers, Alan Parkinson had a figure of 498 and the circumstances of most of these deaths are described in his book Belfast’s Unholy War.[3]

This author cross-referenced the lists compiled by Hassan and Baker, Parkinson’s accounts and reports in the Belfast newspapers as well as summaries compiled for the Provisional Government’s North East Boundary Bureau. In order to be included in the database here, three separate sources were required. The total arrived at by this process matched Parkinson’s figure of 498.[4]

The chronology of killing

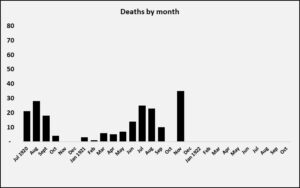

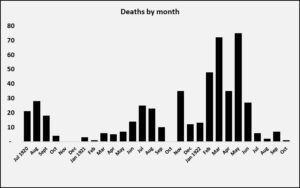

In this section, deaths are recorded as far as possible on the dates on which the incidents occurred, rather than the date of death. Victims could sometimes cling on for weeks or even – in some instances – months after sustaining the injuries that would ultimately prove fatal, so capturing the dates of the incidents gives a more accurate picture of the pattern of violence.

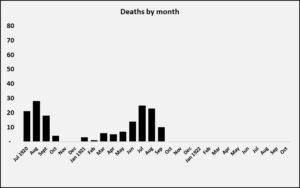

Four distinct peaks can be seen in the killings, the summers of 1920 and 1921, late 1921 and the bloodiest period in the spring 1922.

Four distinct peaks can be seen in the killings.

The initial outbreak of violence was on 21st July 1920, when thousands of Catholics and “rotten Prods” – socialists and trade unionists, also viewed as “disloyal” – were expelled from their jobs in Belfast’s shipyards. Similar expulsions took place in other prominent Belfast firms in the following days. Sectarian rioting broke out and in four days, twenty-one people were killed.[5]

For a month, Belfast was relatively quiet, but worse violence flared after the funeral of RIC District Inspector Oswald Swanzy on 25th August; he had been killed by the IRA in Lisburn several days earlier. In the week that followed, thirty-three people were killed.

(Click on graphs and maps to enlarge)

The next major outbreak came at the end of September, following the killing by the IRA of RIC Constable Thomas Leonard while attempting to disarm him; he was the first policeman to be killed in Belfast since the start of the pogrom. Ten people died over the next few days, including the first victims of what nationalists came to call the police “murder gang” – a group within the RIC who carried out reprisals for the deaths of policemen, killing nationalists and republicans in their own homes and in nearly every case, leaving witnesses behind, usually family members.[6]

The next major outbreak came at the end of September, following the killing by the IRA of RIC Constable Thomas Leonard while attempting to disarm him; he was the first policeman to be killed in Belfast since the start of the pogrom. Ten people died over the next few days, including the first victims of what nationalists came to call the police “murder gang” – a group within the RIC who carried out reprisals for the deaths of policemen, killing nationalists and republicans in their own homes and in nearly every case, leaving witnesses behind, usually family members.[6]

In the spring of 1921, a new active service unit in the IRA began targeting police in Belfast’s city centre. In three separate attacks, they killed seven members of the RIC, although none of those were members of the Belfast RIC: two were officers from the south escorting a witness to the trial in Belfast of an IRA member, two were Auxiliaries on leave in Belfast and three were Black & Tans in Belfast to collect lorries and bring them back to their depot in Gormanstown, Co. Meath. Two of these incidents prompted revenge killings by the RIC “murder gang.”[7]

The second peak in killings came in the summer of 1921. On 10th June, the IRA killed Constable James Glover, who they had identified as a member of the “murder gang.” Thirteen people were killed over the next few days, including three Catholic civilians killed by the “murder gang.”

Of the twenty-five people killed in July, all but one died in the aftermath of an IRA ambush on an RIC patrol in Raglan Street in the Lower Falls on 10th July, the day before the Truce came into effect, but one which became known as “Belfast’s Bloody Sunday”. The killings in August were similarly concentrated, all but two of the twenty-three coming in the last three days of the month.

The third peak came in November 1921, which was the worst month yet.

Two significant developments led to thirty-five killings in the last ten days of that month. The first was that responsibility for security and policing was handed over from the British government to the Unionist government of Northern Ireland, established earlier that year under the terms of the Government of Ireland Act. One of their first acts was to re-mobilise the Ulster Special Constabulary (USC), known as the “Specials”, who had been stood down under the terms of the Truce.

The second development was that the IRA began mounting indiscriminate sectarian attacks on trams: on 22nd November, a bomb, or grenade, was thrown into a tram carrying shipyard workers in Corporation Street, killing three (their names were omitted from Hassan’s list of deaths). A similar attack happened in Royal Avenue two days later, this time targeting a tram destined for the unionist Shankill Road – four people were killed.[8]

The final, most savage and most prolonged peak of killings was not in response to the signing of the Treaty but came in the spring of 1922. This period differed from earlier upsurges in that the killings were not concentrated in a few days – now, they were continuous and sustained.

In the four months from February to May, 230 people were killed, more than in the preceding nineteen months combined. This period also saw the three worst incidents of the whole pogrom period in terms of multiple fatalities.

On 13th February, a bomb was thrown into a group of Catholic children playing in Weaver St in north Belfast: four children and two women were killed.[9]

On the night of 23rd – 24th March, in response to the killing by the IRA of two Special Constables earlier that day, the RIC “murder gang” broke into the home of publican Owen McMahon; all the male members of the household were lined up in the front room, at which point the police opened fire on them. McMahon, four of his sons and his lodger were all killed; two of his sons survived.[10]

The “murder gang” struck once more on the night of 1st – 2nd April, again in response to the killing of a policeman. In what became known as the “Arnon Street killings” (although two attacks took place in other streets), five people were killed in their homes, among them a seven-year-old boy and also including the boy’s father, who was bludgeoned to death with the sledgehammer used to smash open the family’s front door.[11]

May saw the launching of the IRA’s ill-fated Northern Offensive, organised with the assistance of both sides of the Treaty split in the south. This was the single worst month of the entire pogrom period, with seventy-five killings.

May also marked another overtly sectarian attack mounted by the IRA, this time in a cooper’s yard in Little Patrick Street in the north of the city: five workmen there were lined up and asked their religions, the single Catholic was let go and the four Protestants were shot – three were killed.

The failure of the IRA’s offensive and the introduction of internment by the Unionist government, as well as other provisions of the Special Powers Act, meant the scale of violence gradually diminished over the summer of 1922.

On 5th October, a Catholic woman, Mary Sherlock, went to buy food for her family’s dinner. As she queued in a butchers on the Newtownards Road in east Belfast, a gunman walked up behind her and shot her in the head. She was the 498th person to be killed but she was the final fatality of the pogrom.[12]

Deaths not included

Among the list of deaths compiled by Fr Hassan, there are sixteen which, for various reasons, are not included in the total of 498.

In compiling the database, accidental deaths were excluded. While not all victims were individually targeted in particular by their killers, a clear intention to kill someone was required for inclusion – for example, those killed in the IRA tram bombings.

Four of those named by Hassan were victims of accidental shootings, fatally wounded when guns went off unintentionally. Matthew Parke was the stepson of a policeman who, on 9th August 1920, found his stepfather’s gun in a drawer and was playing with it when he pulled the trigger by mistake and shot himself.[13] Private Frederick Bundy was killed on 21st November 1920 when a fellow soldier was cleaning his rifle and it went off.[14]

Deaths due to firearms accidents have not been counted.

The family of William Cowan were at pains to point out that his death on 14th April 1922 had been accidental – in the death notice they placed in the Northern Whig newspaper, they stressed that there should be no retaliation.[15] On 30th April 1922, Ellen Greer was examining the gun of a friend who was a Special Constable when it went off, killing her.[16]

Two of those listed by Hassan were victims of incidents which happened outside Belfast. On 4th November 1920, RIC Sergeant Sam Lucas died in a Belfast hospital – however his wounds had been received in the course of an IRA attack on the RIC barracks in Tempo, Co. Fermanagh.[17] Hassan recorded the death of a “Private Hepworth” on 25th February 1921; in reality, this referred to the death of RAF Flight Officer Hepworth Ambrose Vyvian Hill, who was shot when he failed to answer the challenge of a sentry at Aldergrove Aerodrome near Lough Neagh.[18]

Two deaths on Hassan’s list were not pogrom-related. William Bell, who died on 2nd December 1920, was killed when a wall fell on him during a thunderstorm.[19] Head Constable John Boyd was killed on 22nd March 1922 when he was shot by a suspected burglar whose house he was searching.[20]

Two of the victims were double-counted by Hassan. The first of these cases involved Henry Bowers, shot on 30th August 1921 and “Robert Barnes” also listed on that date, a likely mis-hearing of Bowers’ surname and for whose death no corroboration could be found in any of the Belfast newspapers.[21] The second case of double-counting was that of Charles Harvey, who Hassan listed on the day that he was wounded, 30th August 1921, and again when he died on 6th September 1921.[22]

Six of the deaths listed by Hassan could not be corroborated by reports in any of the Belfast newspapers.

A final death as a result of an accidental shooting was not included in Hassan’s list, nor is it included in the total of 498 here – that of Joseph Burns, who died having been shot on the night of 12th – 13th January 1922. He is named as a member of Na Fianna on the Co. Antrim Memorial to Republican dead in Belfast’s Milltown Cemetery, but for years, an element of mystery surrounded his inclusion on this memorial, as his death was not reported in any of the Belfast newspapers.

The mystery was only finally resolved when his Military Service Pension Collection (MSPC) file was released: this describes how Burns was cleaning weapons along with two IRA members that night, when a gun went off, fatally wounding him. In 1932, Burns’ mother wrote to the MSP Board, saying that “I had to take his death quietly as the police were making active enquiries in the case…” [23]

Identities of those killed

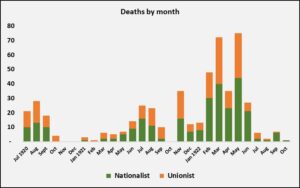

If “nationalists” are defined as members of the IRA or Na Fianna and Catholic civilians, and “unionists” defined as British troops, members of the RIC, RUC or USC and Protestant civilians, then we can see an immediate disparity in the fatalities.

Catholics or nationalists were highly over-represented in casualty figures given their share of Belfast’s population.

The population of Belfast in the 1911 Census was split 24% Catholic and 76% Protestant.[24] But the 498 killings were split 56% nationalist and 44% unionist, so nationalists’ share of the fatalities was more than double their share of the population.

In addition, if we look at the relative numbers of killings over time, then the pogrom can be seen to be composed of two distinct phases.

In the sixteen months up to October 1921, there were 165 killings – 81 nationalists and 84 unionists. In other words, an almost-even split.

But as noted above, in November 1921, the Unionist government of Northern Ireland gained control of policing and security and re-mobilised the USC. In the twelve months from then until the end of the conflict in October 1922, there were 333 killings, twice as many as in the first sixteen months. However, in this period, the tide turned decisively against nationalists – they were the victims in 199, or 60% of these killings.

Civilians were far more likely to be killed in Belfast than soldiers, policemen or paramilitaries, but many civilians who died were engaged in rioting and therefore ‘combatants’ of a sort.

If we sub-divide those killed according to which organisation (or none) they belonged to, then we see that the state forces – British military, RIC, RUC and Specials – made up only 7% of the total. Four British soldiers were killed, twenty regular police (including the seven southern-based officers killed in the spring of 1921) and thirteen Specials.

Using intelligence supplied by sympathetic policemen, two of the RIC officers killed had been identified by the IRA as being members of the “murder gang”: Constable James Glover, already mentioned, and Constable Christy Clarke, killed on 13th March 1922.

One soldier and one Special Constable were killed by state forces in what would nowadays be termed “blue on blue incidents”: on 31st August 1920, Private James Jamieson walked across the line of fire of other members of his patrol who were shooting at rioters on Linfield Road and on 12th March 1922, Special Constable Charles Vokes was killed by British soldiers while attempting to escape from a military patrol which had arrested him earlier that evening.[25]

On the nationalist side, twenty-three members of the IRA and six of Na Fianna were killed. There is an important caveat about these figures: successive releases of files from the MSPC have revealed that some nationalists killed, previously thought to have been civilians, were actually members of one of the Republican organisations; it is quite possible that future MSPC releases will reveal more such cases.[26]

So far, MSPC files have been released for fifteen of the twenty-three IRA members killed.[27] In addition, three other IRA members killed were identified as such in the pension files of other veterans of the Belfast Brigade. One of these had also previously been named as an IRA member by relatives speaking to the authoritative Belfast historian Jim McDermott.[28]

Little doubt surrounds the membership of the remaining five IRA members killed: two were victims of the RIC “murder gang”, Seán Gaynor, killed on 26th September 1920 and Dan Duffin, killed on 23rd April 1921, both listed on the Co. Antrim Memorial in Milltown Cemetery.

Murtagh McAstocker, killed on 25th September 1921, was given an IRA funeral, as was Edward McKinney, an employee and lodger of Owen McMahon, killed in the same incident as the family members. Frank McCoy, killed on 14th February 1922, was another named as an IRA member by McDermott.[29]

MSPC files have been released for five of the six Fianna members included in the total of 498.[30]

However, members of all combatant organisations, whether state or Republican, make up only 13% of the killings. The remaining 432 are split between 251 Catholic and 181 Protestant civilians. To describe all of these as “non-combatants” would be a misnomer, as many were killed during rioting.

But many more were innocent of any violent activity at the time they were killed: people shot in their homes by stray bullets; people abducted and killed by the police “murder gang”; people shot by snipers from the other side while trying to flee to safety; people killed at, or on their way to or from work; children killed while playing or on their way to Sunday School; people caught by hostile mobs in the wrong place or on the wrong tram.

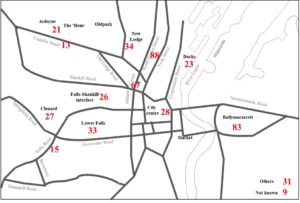

The geography of killing

Having looked at the when and the who, the final area to examine is where the killings occurred.

The lists compiled by Hassan and Baker gave the home addresses of those killed, but in this section, deaths are recorded as far as possible in terms of where the fatal incidents took place – again, the intention is to provide a more accurate picture of the patterns of the violence.

For example, in the initial outbreak of July 1920, three men who lived in the unionist Shankill area were killed – but they were all shot either in or on the edge of the nationalist Clonard district; recording their deaths as having happened in the latter is more informative.

A previous study analysed the deaths according to the city’s local electoral wards.[31] However, for the sake of familiarity, this analysis uses twelve broad areas where most of the killings took place: Ardoyne & The ‘Bone (Marrowbone), Ballymacarrett, the city centre, Clonard, the Crumlin Road, the docks, the Falls – Shankill interface, the Falls Road itself, the Lower Falls, Millfield & Carrick Hill, the New Lodge & Oldpark and York Street & North Queen Street.

The worst of the violence took place in north and east Belfast.

The definitions of these areas are admittedly subjective and some of the boundaries used are somewhat arbitrary; for example, Weaver Street, where the children were attacked while playing, was actually off the York Road, which is a continuation of York Street, but here, Weaver Street is included under “York Street & North Queen Street.”

Areas where fewer than ten killings took place – for example, the Market – are grouped together under “Others.” Finally, some casualties, either already dead or fatally injured, were carried into hospital and it is unclear from press reports where they had been wounded – these are treated as “Unknown.”

Given that the largest concentration of nationalists in Belfast lived in the west of the city – on the Falls Road and in the districts off it (Clonard, the Lower Falls and the streets of the Falls – Shankill interface) – then one might expect that this was where most of the killings took place.

But as the map below shows, it was actually north Belfast – stretching from the docks through to York Street & North Queen Street, Millfield & Carrick Hill, the New Lodge & Oldpark and on out the Crumlin Road to Ardoyne & The ‘Bone – which bore the brunt of the violence. York Street & North Queen Street was the district with the single highest total of killings, at 88.

Across the river in east Belfast, Ballymacarrett was a significant outlier: largely consisting of, but not confined to, the nationalist Short Strand district, this part of the city had the second-highest number of killings, at 83.

A further level of detail can be seen if we sub-divide the killings in each district according to the presumed allegiances of the dead.

| Nationalist | Unionist | Total | |

| Clonard | 20 | 7 | 27 |

| Falls – Shankill interface | 8 | 18 | 26 |

| Falls Road | 8 | 7 | 15 |

| Lower Falls | 24 | 9 | 33 |

| Sub-total west | 60 | 41 | 101 |

| Ardoyne & The ‘Bone | 12 | 9 | 21 |

| Crumlin Road | 10 | 3 | 13 |

| Docks | 18 | 5 | 23 |

| Millfield & Carrick Hill | 40 | 27 | 67 |

| New Lodge & Oldpark | 18 | 16 | 34 |

| York St & North Queen St | 60 | 28 | 88 |

| Sub-total north | 158 | 88 | 246 |

| Ballymacarrett | 38 | 45 | 83 |

| Sub-total east | 38 | 45 | 83 |

| City centre | 3 | 25 | 28 |

| Other | 16 | 15 | 31 |

| Not known | 5 | 4 | 9 |

| Sub-total others | 24 | 44 | 68 |

| Total | 280 | 218 | 498 |

In west Belfast as a whole, nationalists made up 60% of the 101 fatalities, but in both Clonard and the Lower Falls, the figure was over 70%. Across the whole of north Belfast, nationalists were 64% of those killed, but in the worst district for violence, York Street & North Queen Street, this rose to 68%. Once again, Ballymacarrett in east Belfast was an outlier but in another sense, being one of only three districts where more unionists were killed than nationalists.

So why, if most nationalists lived in west Belfast, did two-thirds of the total number of killings take place in north and east Belfast? There are two possible explanations.

One is that, precisely because so much of the city’s sectarian geography was well-established by 1920 and nationalists were concentrated in west Belfast, the greater homogeneity on and around the Falls Road meant nationalists in west Belfast had strength in numbers as a defence against attack from outside.

In contrast, the communities in north Belfast were, at the time, more mixed – even as late as the 1960s, unionists still lived in the New Lodge which nowadays would be considered a republican stronghold.

In north Belfast, being less concentrated, nationalists were more vulnerable to attack. Similarly, they were relatively weak in east Belfast – there, a small nationalist enclave had its back to the River Lagan but was otherwise surrounded by unionist opponents.

The other potential explanation – perhaps related – has to do with the development of the IRA in the city.

The Belfast Battalion was initially established in the nationalist heartland of west Belfast and it was not until September 1920 that a 2nd Battalion was formed – its constituent companies were based in various nationalist pockets elsewhere in the city: A Company in Ardoyne & The ‘Bone, B Company in Ballymacarrett, C Company in the Market and D Company in the New Lodge and North Queen Street. Two more battalions were formed after the Truce of 1921, but the records that remain of these battalions are so scant that it is impossible to say with certainty where they were based.

Of the 984 Belfast Brigade members still living in Ireland in the 1930s whose addresses are known, 636 or almost two-thirds, lived in west Belfast.[32] Even though many of these 1930s addresses may obscure the degree to which people had moved between districts in the city since the 1920s, it is clear that the IRA was far more organised in west Belfast and thus in a far better position to provide some level of armed defence to the nationalists living there. In north Belfast, by contrast, the IRA was much weaker and so could offer less protection to nationalists.

Conclusions

There were two distinct periods within the pogrom.

In the first, from July 1920 – October 1921, while the general level of underlying violence was almost incessant, actual killings generally peaked when unionists reacted violently to particular actions of the IRA – for example the killings of DI Swanzy, Constables Leonard and Glover and the Raglan Street ambush.

However, the balance of killings between the two sides was almost even in this period, indicating that while the IRA and others could not completely defend nationalist areas from attack, nationalists could at least give as good (or bad) as they got.

The turning point of events in the south was the signing of the Treaty in December 1921. But the turning point in Belfast came a month earlier in November, when the Unionist government gained control of the RIC and re-mobilised the Special Constabulary.

Violence in 1922, after the Northern Ireland government took over security, was considerably more one-sided than what went before.

This represented a significant realignment of forces and ushered in the second period of the pogrom, which lasted until October 1922. Now, rather than being sporadic and concentrated into periods of a few days, the killings were almost constant. Now, while there continued to be violent responses by the police “murder gang” to IRA actions – as with the McMahon family and Arnon Street killings – broader unionist violence was less reactive and seemed more aimed at suppressing nationalism entirely. However now, rather than holding their own, nationalists began to be overwhelmed by unionists in and out of uniform and made up 60% of those killed.

The geographical spread of killings within Belfast shows that the worst of the violence took place not, as might be supposed, in west Belfast where nationalists were at their most numerous, but rather in the north and east of the city, where they were at their most vulnerable – in the case of the former, where the communities were less homogeneous, and in the latter where a pocket of nationalists was isolated.

Along with Dublin and Cork, Belfast was clearly one of the most violent places in Ireland, but the proportion of civilians killed was far higher in Belfast.

Some context for the killings in Belfast during the pogrom is provided by The Dead of the Irish Revolution: this catalogues 2,344 people who died from political violence in Ireland between 1917 – 21.[33] This total includes 212 in Belfast, so leaving 2,132 who died elsewhere on the island, the vast majority of them in the three-year period from January 1919 to December 1921. In Belfast, 498 people were killed in just over two years.

So along with Dublin and Cork, Belfast was clearly one of the most violent places in Ireland during the entire revolutionary period. What distinguishes it from anywhere else on the island is the degree to which that violence was consciously directed at civilians – 87% of those killed in Belfast were not members of state or Republican combatant organisations.

The violence in Belfast was not one-sided, nor were sectarian attacks the exclusive preserve of one side. But as previously noted, in a city in which nationalists made up just under a quarter of the population, they were the victims in over half of the killings. So, it is clear that the political violence of the Belfast pogrom was perpetrated against this minority to a hugely disproportionate degree.

For a 2022 update to this research see: The Dead of the Belfast Pogrom, Addendum.

Kieran Glennon is the author of From Pogrom to Civil War – Tom Glennon and the Belfast IRA

References

[1] Robert Lynch, The People’s Protectors? The Irish Republican Army and the “Belfast Pogrom,” 1920–1922, Journal of British Studies, Vol. 47, No. 2 (April 2008), p377

[2] G.B. Kenna. (pseudonym of Fr John Hassan), Facts and Figures of the Belfast Pogrom 1920–22 (O’Connell Publishing, Dublin, 1922 – reprinted, Belfast, 1997), pp161-172

[3] Joe Baker, The McMahon Family Murders (Glenravel Publications, Belfast, 2003); Robert Lynch, The Northern IRA and the Early Years of Partition 1920–1922 (Irish Academic Press, Dublin, 2006), p227; Peter Hart, The IRA At War 1916–1923 (Oxford University Press, Oxford, 2005), p248; Alan Parkinson, Belfast’s Unholy War (Four Courts Press, Dublin, 2004)

[4] In seven cases, two sources were accepted, provided that at least one of these was a contemporary Belfast newspaper

[5] Parkinson, Belfast’s Unholy War, p33; Michael Farrell, Northern Ireland: The Orange State (Pluto Press, London, 1980), p28; Austen Morgan, Labour and Partition, The Belfast Working Class 1905-23 (Pluto Press, London, 1991), pp270-1

[6] For an extensive description of the activities of the RIC “murder gang”, see Confidential Report on D.I. Nixon, Blythe Papers, UCD Archives Department (UCDAD), P24/176

[7] Roger McCorley statement, Bureau of Military History (BMH), Military Archives (MA), WS 0389; Séamus Woods interview with Ernie O’Malley in Síobhra Aiken, Fearghal Mac Bhloscaidh, Liam Ó Duibhir & Diarmuid Ó Tuama (eds) The Men Will Talk to Me: Ernie O’Malley’s Interviews with the Northern Divisions (Kildare, Merrion Press, 2018)

[8] IRA member Seán Montgomery admitted in an unpublished memoir to having been involved in the Corporation Street attack: Statement of Seán Montgomery, O’Mahony Papers, National Library of Ireland (NLI), Ms 44,061/6

[9] For a detailed account of this incident, see https://treasonfelony.wordpress.com/2016/02/04/the-weaver-street-bombing-and-not-dealing-with-the-past/

[10] Parkinson, Belfast’s Unholy War, p230-231; Baker, The McMahon Family Killings, p6-21

[11] Extracts from statutory declarations on Arnon Street and Stanhope Street massacre, National Archives of Ireland, D/Taoiseach S1801

[12] Freemans Journal, 6th October 1922

[13] Belfast News Letter, 10th August 1920

[14] Named by Hassan as “Private Arthur Bundry” – Kenna, Facts and Figures of the Belfast Pogrom 1920–22, p161; https://www.cairogang.com/soldiers-killed/bundy-fa/bundy.html

[15] Northern Whig, 17th & 20th April 1922

[16] Belfast News Letter, 4th May 1922

[17] Belfast News Letter 24th November 1920

[18] https://www.cairogang.com/soldiers-killed/hill-hav/hill-hav.html

[19] Belfast News Letter, 4th December 1920; two others died in the same incident but their names were not listed by Hassan

[20] http://policerollofhonour.org.uk/forces/ireland_to_1922/ric/ric_roll.htm

[21] Kenna, Facts and Figures of the Belfast Pogrom 1920–22, p164

[22] ibid

[23] Joseph Burns file, Military Service Pensions Collection (MSPC), MA, DP934; Burns’ death, though not the circumstances of it, was reported in the Freemans Journal, 14th January 1922

[24] http://www.census.nationalarchives.ie/exhibition/belfast/main.html

[25] https://www.cairogang.com/soldiers-killed/jameison/jamieson.html; Belfast News Letter, 21st March 1922

[26] For example: John (or Jack) Coogan, killed on 30th August 1921 in North Queen Street – he is referred to as an IRA member at https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_members_of_the_Irish_Republican_Army#K_3; Augustine Orange, killed on 19th March 1922 in Clermont St off the Albertbridge Road in Ballymacarrett – he is listed in the pamphlet, Antrim’s Patriot Dead (Belfast, National Graves Association, n.d.), p75. In either of these cases, an MSPC file could confirm their IRA membership, but none has yet been released.

[27] John O’Brien, MSPC, MA, 2RB109; Edward Trodden, MPSC, MA, 1D153; Michael Garvey, MSPC, MA, DP376; Alexander Hamilton, MPSC, MA, 1D147 – claim rejected but listed as a member of A Company “killed in action” in Nominal Roll of 3rd Northern Division, 1st Brigade (Belfast), 4th Battalion, MA, MSPC/RO-406; James Ledlie, MSPC, MA, 1D325; Frederick Fox, MSPC, MA, 1D38; Bernard Shanley, MSPC, MA, 1D145; David Morrison, MSPC, MA, 1D168; Thomas Gray, MSPC, MA, DP1832; James Morrison, MSPC, MA, 1D212; Andrew Leonard, MSPC, MA, 1D398; James Magee, MSPC, MA, 1D213; John Walker, MSPC, MA, 1D446; Arthur McCaughey, MSPC, MA DP8007; William Thornton, MSPC, MA, 1D127

[28] Thomas Giles, killed on 22nd July 1920, and John McCartney, killed on 25th July 1920 (not to be confused with another Belfast IRA member, Seán McCartney, killed on 8th June 1921 at Lappinduff, Co. Cavan), both identified in David Matthews, MSPC, MA, MSP34Ref60258; Henry Mulholland, killed on 10th July 1921, identified in Robert Graham, MSPC, MA, MSP34Ref6078; Jim McDermott, Northern Divisions – The Old IRA and the Belfast Pogroms 1920–22 (Beyond The Pale Publications, Belfast, 2001), p283, note37

[29] McKinney was buried in his native Donegal; Montgomery statement, O’Mahony Papers, NLI, Ms 44,061/6. Re McCoy, see McDermott, Northern Divisions, p168

[30] John Murray, MSPC, MA, 2RBSD107; Thomas Heathwood, MSPC, MA, DP4309; William Toal, MSPC, MA, DP6722; Leo Rea, MSPC, MA, 2D504; Joseph Hurson, MSPC, MA, 2D502. The sixth, for whom no MSPC file has yet been released, was James Smith, shot on 18th April 1922 in Mayfair Street in The ‘Bone and listed on the Co. Antrim Memorial in Milltown Cemetery as “J.P. Smyth”, killed on the same date

[31] Niall Cunningham, Mapping the Doctrine of Vicarious Punishment: Space, Religion and the Belfast Troubles of 1920–22, paper delivered to European Social Science History Conference at Glasgow University on 14th April 2012

[32] Nominal Rolls, 3rd Northern Division, 1st Brigade (Belfast), MSPC, MA, MSPC/RO/402-406A; Applicants Resident in the Six Counties General File, MSPC, MA, SPG/10; Special Investigation of Six County Cases, MSPC, MA, SPG-10A2; Thomas Gunn memoir, ‘Reorganisation in Antrim’, Michael Collins Papers, MA, MA/CP/062/001; 1917-21 Medal recipients, http://mspcsearch.militaryarchives.ie/brief.aspx

[33] Eunan O’Halpin & Daithí Ó Corráin, The Dead of the Irish Revolution (Yale University Press, New Haven, USA, forthcoming)