Democracy in Ireland – A Short History

A short history of democracy and the right to vote in Ireland, By John Dorney.

A short history of democracy and the right to vote in Ireland, By John Dorney.

Liberal democracy, since the end of the Cold War has been almost unchallenged as the hegemonic political idea of our age.

Even the most dictatorial regimes pretend to be democratic and make noises about citizens’ equality and the rule of law.

However, we often forget how comparatively recent a phenomenon mass democracy is. Before the First World War only a handful of states had anything approaching democratic systems by modern standards and even in the most representative republics – the USA and the French Third Republic, women were excluded. Only after 1989, with the fall of the Soviet backed regimes in central and eastern Europe did democracy with universal suffrage become the majority political system even in Europe.

We often take democracy for granted, forgetting how recent a phenomenon it is.

A government chosen by universal suffrage of the citizens is therefore not something to be taken for granted. Ireland benefited from the gradual democratisation of the United Kingdom in the 19th century and after the formation of the Irish Free State in 1922, that entity and its successors are one of the few examples of unbroken democratic governance throughout the 20th century.

But the route from monarchy to oligarchy to democracy has not been straightforward anywhere and Ireland’s story is no different in that respect. But Ireland also had the added complication of colonisation and religious discrimination.

This piece therefore attempts to show the highways, byways and dead ends along the road to universal suffrage in Ireland and to trace gradual extension of the right to vote.

The 18th century to Catholic Emancipation

The original Irish Parliament was an invention of the Anglo-Norman conquest. It dated back to 1297, when the Lord Chief Justice of the Lordship of Ireland, Sir John De Wolgan, first called an elected assembly of Anglo-Norman Lords, Bishops and Commoners. The Parliament met only when the King called it, in order to pass new laws or new taxes. The medieval Irish Parliament might, as it did in the 1570s, try to resist the imposition of new taxes, but no one expected it to act as the government of the country. To the extent that English control existed in Ireland outside the area around Dublin before the 17th century, it was administered by the Lord Lieutenant or more commonly the Lord Deputy.

The Irish Parliament in the 18th century amassed more power relative to the Crown, but remained all-Protestant. After Catholic Emancipation in 1829 the electorate was radically cut

This remained the case until the early 18th century, when in 1692 the Parliament declared it had, ‘sole right’ to legislate for taxes in Ireland. While only four parliaments were called in the whole 17th century, the body was in session throughout the 18th, with the sole exception of the years 1699-1703, gradually assuming more power. In 1782 it successfully asserted that the Westminster Parliament had no right to block laws passed in Ireland.

However, as the Irish elected assembly gained in power, it paradoxically became less representative. In 1613, in order to approve the seizure of Catholic owned land for ‘plantations’ or settlement of Protestant colonists, electoral boundaries were redrawn to give Protestants a majority. Catholics (around 80% of the population) were banned from holding public office (from the House of Commons in 1691 and from the Lords in 1716) and banned from voting altogether in 1728.[1]

This began to change in 1793, when Catholics and all male property holders of over 40 shillings were allowed to vote for the Irish Parliament. Still at this stage only Protestants could hold office. Constituencies were also very unevenly distributed.

Conceivably, this could have been the beginning of the evolution of an Irish democracy, but it was not to be. Liberal reformism headed by Grattan’s ‘Patriots’ ran into ‘Ultra-Protestant’ reaction. Radicals (Catholic, Anglican and Presbyterian) formed the Society of the United Irishmen, inspired by the revolution in France, to create an egalitarian, independent Irish republic, including universal male franchise. Of course, it did not happen. Instead the United Irish insurrection of 1798 was bloodily suppressed and just two years later the Irish Parliament, on the cajoling of the British government, voted itself out of existence altogether in the Act of Union.

Post union, people continued to vote in Ireland but the 103 Irish MPs in Westminster would forever be a minority there. The actual government of Ireland, based in Dublin Castle was formed by the Lord Lieutenant, the King’s representative, nominated by the Imperial government, The Chief Secretary for Ireland, an MP likewise appointed and the Under Secretary, a senior civil servant. Therefore, despite the extension of the right to vote in Ireland throughout the 19th century, there remained a democratic deficit, since those elected in no sense governed the country under the Union.

Moreover, until the third decade of that century, Catholics could not hold public office including the position of Member of Parliament. When in 1829 this demand, known as Catholic Emancipation was conceded, so that Catholics (and dissenting Protestants and Jews for that matter) could hold public office, the electorate in Ireland was actually radically cut so that Catholics would not dominate Protestants. In a population of c.8 million the electorate was cut from 216,000 to 37,000 men as the property qualification for voting was raised from 40 shillings to £10 income per year.[2]

Catholic emancipation in other words represented, in the short-term anyway, one step forward and two steps backwards for democracy in Ireland. However it did establish the principle that all male subjects of the realm were equal before the law – a step that should not be underestimated given that it was not until three years later that slavery was abolished in British possessions in Africa and the Caribbean.

Electoral Reform in Victorian Ireland

What the United Kingdom was moving towards was a system where government would represent all those who paid it taxes.

In 1832 the Representation of the People (Ireland) Act slightly extended the franchise by including £10 freeholders, those who held leases for life and leaseholders of at least 60 years. [3]

In 1850 the Reform Act gave the vote to every man with total property of 12 pounds, raising the electorate to c.16% of adult men in Ireland. It was again extended slightly in 1867. In 1872 the secret ballot was introduced so people did not have to fear reprisals, especially from landlords, for their votes.The 1884 Representation of the People Act lowered the property threshold again, so that about 50% of the adult male population had the vote (compared to about 60% in England, where incomes were higher).[4]

However, outside of simply counting the franchise, other anomalies existed in terms of democracy in Ireland. The principle of a hereditary right to vote was the principle one. One manifestation of this was the House of Lords – whose members simply inherited their seats. There were 28 Irish peers in the House of Lords throughout the 19th century.

The 19th century saw many democratic reforms in Ireland, but at its close, still only 30% of adult men had the vote.

Today the House of Lords in Britain is of largely symbolic importance, but up to 1909 it could veto any Bill passed in the (elected) House of Commons, this affected Ireland most clearly in 1893 when the Liberal government passed the Second Home Rule Bill –granting self-government for Ireland, only to see it voted down in the Lords.

The other area of hereditary voting was a relic of the medieval guilds, where ‘freemen’ – members of a guild and his male children – had the franchise in both local and general elections. Since the guilds had matured in the age of Protestant Ascendancy in Ireland, their members were all Protestant and in Dublin especially were bastions of working class Protestant resistance to electoral reform in the early 19th century.

Nevertheless, the freemen’s right to vote fell before the Liberal Under-Secretary for Ireland Thomas Drummond, who in 1840 reformed the election of Corporations so that voting was made on the basis of property (of over £10 per year) rather than religion and the freemen’s vote was abolished.[5]

In 1898, the franchise in local government elections was extended so that all householders and occupants of a portion of a house could vote in local elections.[6] While this is often hailed, not entirely without reason, as a major breakthrough for democracy in Ireland, it did not entirely respect the principle of ‘one man one vote’, as large rate payers could sometimes exercise more than one franchise – having as many votes as they had rate-paying properties. In the 20th century, especially in Northern Ireland, this would emerge as an issue of serious discontent.

1918 and after

The great watershed for democracy based on universal suffrage in Ireland came in 1918 at the end of the First World War. Mainly because it was recognised that to ask total war of a population entailed also giving it total representation, the vote was granted to almost all adult men and for the first time ever, to women.

An election was held in December of that year (just one month after the end of the Great War) throughout the United Kingdom, in which the vote was extended to almost all adult males over 21 and all women over 30 with some property restrictions. In Ireland, as yet undivided, this almost tripled the electorate from 700,000 to over two million[7].

Due to this and other factors such as the postponement of Home Rule, the Easter Rising and the campaign against conscription, the 1918 election in Ireland also had explosive implications in Ireland for the other facet of democracy, how much power to govern Ireland would elected representatives have?

The revolutionary First Dail of 1918 declared an independent Irish Republic in existence, whose sovereignty was based on the popular vote given to Sinn Fein the 1918 election. (For details of subsequent events see The Irish War of Independence – A Brief Overview).

The 1918 Representation of the People Act tripled the electorate in Ireland and also led directly to Irish independence.

Matters did not work out quite as they wished of course. The 1920 Government of Ireland Act created two Home Rule Parliaments, Southern Ireland based in Dublin and Northern Ireland based in Belfast. This partition of Ireland was confirmed under the 1922 Anglo-Irish Treaty, though Southern Ireland was replaced with the all-but-independent Irish Free State in all of the island outside the 6 north-eastern counties that comprised Northern Ireland.

Democracy in independent Ireland

Notwithstanding the Civil War of 1922-23, the Free State did emerge as parliamentary democracy. In 1923, the vote was extended to all women over 21 and the remaining property qualifications were also abolished. In 1973, after a referendum the vote was extended in the Republic to all adults over the age of 18.

However, some aspects of independent Ireland were actually less democratic than what had gone before. Power was stripped from local government by the Cumann na nGaedheal administration of 1923-32 and given instead to unelected ‘County Managers’. While this was in part due to Civil War animosities, it was also due to the belief, held also by many in Cumman na nGaedheal’s main political rivals, Fianna Fail, that the County Councils and Corporations since 1898 had been nests of corruption. Fianna Fail extended the County and City Manager system throughout the country in 1940[8]

Rates and their link of the vote in local elections to property were abolished in 1977 but this also meant that local government was even more dependent now on central government funding. While promises have sometimes been made about restoring power to local government, the current government (2013) has, as part of its austerity measures, proposed to abolish a range of urban and rural councils.

For some time after independence, slightly hostile attitudes towards democracy and the ability of the people to operate it, persisted for a surprisingly long time

What was more, for some time after independence, slightly hostile attitudes towards democracy and the ability of the people to operate it, persisted for a surprisingly long time among the Irish nationalist political elite. Ernest Blythe, for instance, a leading Cumman na nGaedheal politician, pondered in 1930 whether, ‘the gods of democracy have not feet of clay…the franchise in the hands of an ignorant and foolish populace is a menace to the country’.[9]

In 1939 Fianna Fail minister Sean MacEntee lamented that, ‘the married man and his wife has no more voice than the whipper-snapper or flapper [girl] of 21…we have carried the doctrine of political egalitarianism to such extreme lengths that it would be difficult to find a parallel in any predominantly Catholic country’.[10]

Though the Free State and from 1948 the Republic of Ireland have remained wedded to parliamentary democracy, one Irish political analyst identified, ‘deference to the views of established leaders and intolerance to those who dissent from these views’. Contributing to this has been, “a breakdown in the interface between Ireland’s public institutions and the Irish public” and “a presumption of secrecy that underpinned Irish government”.[11]

Democracy in Northern Ireland

Northern Ireland though, the unionist-dominated self-governing region of the United Kingdom created in 1920, had more serious problems with democracy – even leaving aside the nationalist argument that the whole entity was an undemocratic exercise in creating an artificial unionist majority.

Its government, based at Stormont, was elected to its Parliament from 1922 until its abolition in 1972. Like the Free State it extended suffrage to all men and women over 21.

Northern Ireland’s democratic deficit has been one of the principle reasons for conflict there

But through various means it diluted the votes of its Catholic and nationalist minority. The first of these was so-called, ‘gerrymandering’ where nationalists were grouped into constituencies for Northern Ireland elections which under-represented their voting strength. This was most pronounced in the city of Derry where a city with a 61% nationalist majority still elected a unionist majority on the city council.

The main area of contention was local government, where, like the Republic in the same period (though unlike the rest of the UK since 1945), rate-payers had votes calculated according to their property. However, in the North this had the added enervating effect that the mainly Protestant and unionist business community dominated local government even where Catholics were in a majority.

For these reasons, ‘One Man One Vote’ was one of the principle demands of the Northern Ireland Civil Rights Association, whose agitation and the state’s repressive reaction to it, touched off the conflict we still call ‘The Troubles’. [12]

The grievances of 1969 and before regarding voting were largely resolved in the early 1970s. In April 1969 the Unionist Parliamentary Party voted by 28 to 22 to introduce universal adult suffrage in local government elections in Northern Ireland and in 1972, electoral boundaries were redrawn and many services taken under British ‘Direct Rule’, as a means of trying to defuse nationalist grievances and drain support from republican paramilitaries. [13]

Today, with a restored Northern Ireland Assembly at Stormont operating since 2005, there is still arguably incomplete democracy as each Bill passed must receive, not simply an absolute majority but majorities among both unionist and nationalists representatives.

Democracy in both parts of modern Ireland is of course imperfect but it has had a very long evolution and will hopefully continue to develop in a more, not less, inclusive direction.

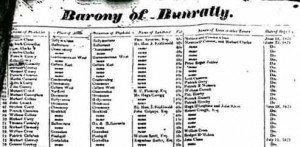

For a guide to historical Irish electoral registers at Irish Family History Centre see here, illustrating the expansion of the right to vote over the centuries.

References

[1] See Padraig Lenihan, Consolidating Conquest, Ireland 1603-1727, p203-211

[2] Patrick Geoghegan, King Dan, The Rise of Daniel O’Connell, 1775-1829

[4] James H. Murphy, Ireland, A Social, Cultural and Literary History, 1791-1891, p116. In 1911 the population of all Ireland was 4.3 million. 700,000 is roughly 16% of 4.3 million. If half the population was female then roughly 32% of all males had the vote in 1910. But if we include only adult males then it would be somewhat higher. According to the 1911 census, roughly 40 % of the population was under 21. Which means that about 50% or so of males over 21 had the right to vote in 1910.

[5] Hill, Jacqueline, The Protestant Response to Repeal, the case of the Dublin working class, in Ireland Under the Union, (Lyons and Hawkins eds), Clarendon 1980. p45-46

[6] http://www.limerick.ie/digitalarchives/limerickcitycouncilandlocalgovernmentcollections/franchiseandelections1869-1954/

[7] http://www.ark.ac.uk/elections/h1918.htm

[8] Tom Garvin, The Evolution of Nationalist Politics p159

[9] Fearghal McGarry, Eoin O’Duffy, A Self Made Hero, p190

[10] Joe Lee, Ireland 1912-1985, p284

[11] Coakley, Gallagher, 1999, Politics in the Republic of Ireland pp 53, 221, 267

[12] See ‘How much discrimination was there under the Unionist regime, 1921-1968?’ by John Whyte at http://cain.ulst.ac.uk/issues/discrimination/whyte.htm

[13] http://cain.ulst.ac.uk/issues/discrimination/chron.htm