March 1923 – The Terror Month

March 1923, the penultimate month of the Irish Civil War, saw some of its most brutal acts. John Dorney looks at what Kerry Republicans remembered as, “the terror month”

The Irish Civil War broke out in late June 1922. What might have been a brief coming to blows between rival IRA factions instead dragged on for many months, in a small-scale but brutal guerrilla and counter-insurgency campaign between the new Free State government and the Anti-Treaty IRA.

As 1922 turned into 1923, it was becoming clear that the guerrillas were not going to topple the Free State, which took increasingly draconian measures –such as wholesale internment and selected executions of captured Anti-Treaty fighters.

The Irish Civil War could have ended long before March 1923

Towards the end of February 1923, the Executive of the Anti-Treaty IRA met in an isolated location named Ballingeary in Tipperary. IRA chief of staff Liam Lynch was told that the guerrilla army was on the brink of collapse. Their 1st Southern Division reported that, “in a short time we would not have a man left owing to the great number of arrests and casualties”. The Cork units reported they had suffered 29 killed and an unknown number captured in recent actions and, “if five men are arrested in each area, we are finished” [1].

Lynch chose to continue the war. The Free State had suspended executions in early February, in the hope that it would help to speed the end of the conflict and the meeting of the IRA leadership must have seemed like the ideal opportunity for them to call it off. For whatever reason, bloody mindedness, fanaticism and idealism are among those attributed to him, Lynch refused.

The following month, known among Kerry Republicans as the “terror month” – March 1923 – would demonstrate the cost in lives and bitterness of such a policy.

The following month, known among Kerry Republicans as the “terror month” – March 1923 – would demonstrate the cost in lives and bitterness of such a policy.

Kerry – last stand of Anti-Treaty republicanism

Kerry had seen more violence in the guerrilla phase of the war than almost anywhere else in Ireland.

The local IRA had been almost entirely Anti-Treaty, and after the National Army’s seabourne landings in August of the previous year, had resisted tenaciously. Kerry was occupied by sometimes brutal National Army troops of the Dublin Guard, a former IRA unit, turned into a regular Army formation but still officered largely by ex-Squad men. By March 1923, 68 Free State soldiers had already been killed there and 157 wounded – a total of 85 would die there by the end of the war [2].

From the start the fighting there had been less than chivalrous, on either side. The Anti-Treaty fighters had targeted medical orderlies and assassinated two local Free State officers – the Scarteen O’Connor brothers – in their beds. The Dublin Guard for their part beat, tortured and sometimes shot prisoners.

March 1923 would be the nadir of the Civil War in the county.

By March 1923, 68 Free State soldiers had already been killed in Kerry and 157 wounded – 85 would die there by the end of the war

The month started in Kerry with an Anti-Treaty attack on Cahirciveen. The Republicans were surprised before they could actually assault the town and dispersed, amid running fights, into the hills to get away. Three National Army and two Republican soldiers were killed and six IRA men captured[3].

A typical, if comparatively bloody, Civil War skirmish.

The Knocknagoshel and Ballyseedy bombs

Two of the dead were close personal friends and ex-IRA comrades of Paddy Daly, in command of the Free State’s Kerry forces.

He announced that in future prisoners would clear mined roads. The day after the Knocknagoshel bomb, nine prisoners from Kerry number one Brigade were taken from Ballymullen gaol in Tralee to Ballyseedy crossroads, ostensibly for this purpose. The troops made sure that they were, “all fairly anonymous, no priests or nuns in the family, those that’ll make the least noise”.[4]

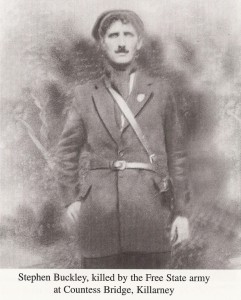

Some of the prisoners had already been beaten by the time they arrived at Ballyseedy, where they were tied around a landmine and literally blown to smithereens. One man, Stephen Fuller, was not killed but blown clear by the blast and lived to tell about the massacre. At the scene, the Free State troops shovelled the remains of the pulverised bodies into nine coffins and drove them back to Tralee with the story that they had been accidentally killed while clearing a mined road. A riot broke out in the town when the relatives of the dead tried to break open the coffins and identify the dead [5].

The ‘Visiting Committee’

If anyone believed that the explosion at Ballyseedy had been an accident, they would have trouble explaining the deaths of nine more Republican prisoners in the next four days.

In fact, the killings seem to have been highly premeditated, a coterie of Dublin Guard officers choosing sample prisoners in turn from each of the Kerry IRA units for ‘exemplary’ execution. Four members from Kerry number two Brigade were blown to pieces in Killarney, also on March 7. One man, Tadgh Coffey, was, like Fuller at Ballyseedy, blown clear and survived.

Five days later, on March 12, another five men, this time from Kerry number three were blown up at Cahirciveen, this time, to avoid any more escapees, having been first shot in the legs.[6].

Before the month was out, two more prisoners were killed in Kerry, simply shot out of hand – bringing the number of prisoners killed in reprisal for Knocknagoshel up to 19. Two prisoners were also officially executed in Tralee in April. [7].

Perhaps the most sinister aspect of the incidents was the Government response –which showed the extent to which they looked the other way at atrocities committed by their troops throughout the war. Richard Mulcahy defended Paddy Daly’s story of accidental deaths in the Dail and an Army inquiry cleared the soldiers concerned[8]. We now know, following the release of documents kept secret until December 2008, that not only did the government know that the prisoners had been murdered, they even knew who did it, a group of Dublin-based troops known as, “the Visiting Committee” in National Army circles [9].

In revenge for Knocknagoshel, 17 prisoners were killed in Kerry within four days and another seven before the month was out.

Wexford and Drumboe

Before March was over, there were two more long-remembered incidents of vicious revenge killings. In Wexford, which had been free of executions up this point, three Republican prisoners were shot on March 13. Bob Lambert, the Wexford IRA commander had three National Army soldiers captured and killed in retaliation [10]. The local Free State forces retaliated by assassinating at least two more local republicans.

In Donegal, National Army troops responded to the death of a soldier in an ambush by executing four prisoners who had been held in Drumboe castle since January[11].

The IRA and the underground Republican “government” proclaimed a period of national mourning for their dead and banned public entertainments and sporting events. An international boxing match in Dublin on March 17 had to be guarded by a battalion of Free State troops and the crowd attending it was attacked with a mine and gunfire[12].

To this dreary catalogue of atrocity could be added dozens of other forgotten incidents from the same month – a lone National Army sentry killed by a sniper in Tralee, four Anti-Treatyites gunned down by machine guns after a failed ambush in Wexford, two assassinations of suspected republicans in Dublin by Free State Intelligence, two off-duty Free State soldiers seized and shot in the same city; and so on. Such was the fruit of civil war. [13].

The end

On May 24th, he ordered the remaining guerrillas in the field to “dump arms”. This was not the same as a surrender – the Civil War never formally finished – but it was effectively the end.

The miserable death of a revolution

The Irish revolution, born out of violence, but also with great hopes, in 1916, died a miserable death in the back-roads of Kerry in the spring of 1923

The men on the ground, on both sides, were in the final stage of years of exposure to and practice of violence since 1919. Looked at in this light, the atrocities of the Civil War on both sides can largely be explained by a grim cycle of retaliation – the need to hit back for hurt caused to one’s own comrades. Many of these men, especially those in the Dublin Guard, had been inured to killing by years of casual and up-close acquaintance. March 1923 demonstrated the depths of cruelty they had reached.

At a higher level, the leadership of both sides failed to avert the descent into internecine slaughter. The Anti-Treaty side made the events of March 1923 possible by prolonging the conflict long after armed resistance to the Irish state made no political, military or tactical sense. On the side of the Pro-Treatyites, the government tolerated elements of their forces murdering prisoners out of hand -a practice they were well aware of. (My fuller thoughts on the character of the Civil War here)

The Irish revolution, born out of violence, but also with great hopes, in 1916, died a miserable death in the back-roads of Kerry in the spring of 1923, like so many revolutions, consuming its own sons.

See also

‘A terror to the countryside’: Civil War reprisals in Cork and Kerry

Listen to an interview with John Dorney on the events of March 1923 here.

The Story of the Irish Civil War is available here.

The Story of the Irish Civil War is available here.

References

[1] Michael Hopkinson, Green Against Green, The Irish Civil War p235-6

[2] Hopkinson, p241, Tom Doyle, The Civil War in Kerry, p324-6

[3] Doyle, p269

[4] According to Niall Harrington, cited in RTE Documentary, The Ballyseedy Massacre, 1997.

[5] Doyle p273-274

[6] Niall C Harrington, Kerry Landing, An Episode of the Irish Civil War, p241

[7] Doyle p270-80

[8] Hopkinson p241

[9] Irish Times, December 31, 2008

[10] Hopkinson p 246

[11] An Phoblacht, March 13, 2003

[12] Andrew Gallimore, A Bloody Canvass, The Mike McTigue Story, p122-134

[13] For a fairly full compliation of incidents, see http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Timeline_of_the_Irish_Civil_War#March_2

[14] Meda Ryan, Tom Barry, p193