The First Battle for the Marrowbone, Belfast 1920

By Gus McKendry

This article is an attempt to examine and analyse the events on the night of 28th and the early hours of the morning of 29th August 1920 in the Marrowbone district of north Belfast, which came under sustained attack from loyalists. This was one week to the day after District Inspector Oswald Swanzy was assassinated in Lisburn on the orders of Michael Collins.

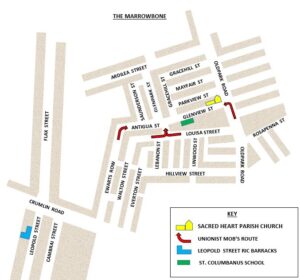

The incident became known as the ‘first battle of the Marrowbone’ during the time known to Irish nationalists as the ‘Belfast Pogrom 1920-1922’. It was the first of many ferocious battles engaged in by the local residents, defending their district from loyalist incursions. Six men from the Marrowbone district of Belfast died as a result of gunfire on the night of 28th and the early hours of the morning of 29th August 1920. Many more were injured. This was the single biggest loss of life in any incident, for the people from Ardoyne and the ‘Bone’ killed during the period. [1]

Six men were killed in Marrowbone in north Belfast in an attack on the area on August 28-29, 1920

The six victims were;

John Leo Murray, 11 Glenview Street.

Owen Moan, 36 Glenview Street.

Thomas Toner, 89 Ardilea Street.

Henry Kinney, 120 Ardilea Street.

William J Cassidy, 42 Glenpark Street,

Charles O’Neill, 9 Glenpark Street.

I have referred to these men as victims, but they also died defending their own families, their homes and their neighbours.

The lead up to the attempted invasion.

The Marrowbone (sometimes nicknamed ‘The Bone’) is a small working class Catholic district of fewer than one thousand people, adjacent to Ardoyne in North Belfast. The ‘Bone’ was surrounded by unionist districts.[2] The people of the Marrowbone district could see the build-up of aggression and attacks by the unionist population on Catholics from July 1920 onwards.

Senior commanders in the army and police were less than enthusiastic about defending nationalist districts, much less taking on the mobs of unionist attackers. There were close links between leading unionists and army and police commanders.[3]

The Royal Irish Constabulary, (RIC) in Belfast from 1919, was under the command of divisional commissioner, Brigadier-General Sir George Hackett Pain, an ultra-unionist and former chief of staff of the UVF. Hackett Pain had played a critical role in organising the 1914 Larne gunrunning. With Hackett Paine in command, there was no prospect of fair treatment for the nationalist population of the city.[4]

Events in Derry, Dromore and Lisburn in the summer of 1920 provided warnings for an attempted attack on the Catholic district of Marrowbone in August 1920.

The Curragh incident of 1914, in which British Army officers indicate they would not act against armed unionist opposition to Home Rule, showed the British officer class was deeply in sympathy with Empire loyalism and hostile to Home Rule. The subsequent issuing of a document, a guarantee, stating that the British Army would not be used against the Ulster Loyalists made it clear beyond doubt.

Some of the soldiers and even the RIC on the ground, may have been sympathetic to the plight of the Catholic community. The RIC rank and file in Belfast at the time were mostly Catholic. They had however, to take orders from their superiors who were unsympathetic and mainly pro-unionist. The security forces, during disturbances, were charged with keeping order but prioritised the protection of the Catholic institutions of Church and schools, as their destruction would be picked up by the International community. The loss of Catholic lives however could easily be excused as the result of intercommunity strife and allegations that those killed were themselves ‘Sinn Feiners’ .

Certainly the perception among the people of Marrowbone was that they had to defend themselves against what one resident described as ‘‘(a) the so called police, (b) the military, and (c) the orange mob’.

The residents of the Marrowbone district could see what was coming. The Derry gunbattle of June 1920 was an early warning. The inflammatory anti-Catholic speeches at Orange demonstrations in July 1920 created a powder keg atmosphere in unionism. Sir Edward Carson’s speeches, linking politics and religion, signalled to the Orange Order that action against supporters of Sinn Fein and the Church of Rome, which to many of his supporters were synonymous, had his tacit support. His inflammatory rhetoric were widely interpreted by working -class loyalists, fired up with Twelfth of July rhetoric, as a call to take action. It was not long before they took matters into their own hands. [5]

Catholic workers were chased from their employment in the shipyards that July, some having to swim for their lives across the River Lagan. Two of the workers injured in the shipyards, Michael Cassidy and Patrick Devlin were from the Marrowbone area while another, Henry Hennessy, a worker in Mackie’s Foundry was shot dead on his way home from work the following day. [6]

These disturbances in Belfast were followed by the Banbridge, Dromore and Lisburn anti–Catholic riots, burnings and lootings in late July which broke out after the assassination of Banbridge native, Colonel Gerald Smyth, an RIC divisional commissioner for Munster, assassinated on IRA Director of Intelligence Michael Collins orders, in the Country Club in Cork City.

One week to the day before the invasion of the Marrowbone district, on 22 August 1920, the Cork IRA, cooperating with Belfast Volunteers, carried out another assassination, that of District Inspector Oswald Swanzy, in Lisburn, again on the orders of Michael Collins. This was in revenge for Swanzy’s alleged role in the assassination of Tomas MacCurtain the Lord Mayor of Cork in March 1920. In the aftermath, local loyalists burned down Catholic owned properties, businesses and the parochial house.

After three days and nights of one-sided violence, in which at least one life was lost in Lisburn, over 1,000 Catholics had to flee from their homes and leave behind their businesses. The damage was assessed as being in excess of £810,000. Seven men were arrested, five were found guilty, their sentences were recorded and they were set free. [7]

The Marrowbone residents knew it would soon be their turn to be attacked, given what was going on throughout Belfast and Lisburn. It was obvious that they could not rely solely on the security forces for protection. In their exposed position they would have to protect themselves or face the same treatment as the Catholics in Lisburn a few days earlier.

The day of the Invasion

From early on Saturday morning the Marrowbone neighbourhood was disturbed by the threatening attitude of small bands from the adjoining unionist localities. As the day progressed these unionist groups began to gather at the corners of the street next to the Marrowbone and antagonised passers-by.

The situation was made worse by the crowd of Linfield supporters returning from a football match. Linfield played Cliftonville in the first match of the season in the Gold Cup, at 3:30 Saturday 28th August 1920, watched by 4,000 in attendance at Cliftonville’s ground at Solitude. The Linfield supporters were from a strongly Protestant unionist background and at that time the club was reluctant to sign Catholic players. As the Linfield supporters passed the Sacred Heart Catholic Church they used obscene language towards some men from the locality. The police had to intervene and the crowd was moved along. These, signs of what was to come, were not mentioned at the inquest.

From early on Saturday morning the Marrowbone neighbourhood was disturbed by the threatening attitude of small bands from the adjoining unionist localities.

Acting on the advice of the priests of the parish, the local people kept to their houses after dark. Things became worse after midnight and a guard of residents were placed around the Church and Parochial House. Threatening unionist mobs had gathered at every point of vantage around the district. This was obviously the preparation for a general attack. Catholic residents in exposed locations had to flee, leaving all their belongings and making their escapes through back yards, climbing walls and running up dark entries to escape drunken mobs. This continued until about one o’clock on Sunday, when the mobs made what was a pre-concerted attack from all quarters.[8]

The police had difficulty preventing the mob getting at the Chapel and Parochial House. The new school in Glenview Street was attacked by the mob who had gathered at Ewart’s Row. Protection of these buildings was a priority for the security forces. This mob was joined by another mob that had unsuccessfully tried to get up the Crumlin Road to attack the neighbouring Catholic district of Ardoyne.

They had been turned back from Ardoyne by a strong force of police and civilians. They retreated to Ewart’s Row in time to participate in the tragic happenings later. This mob, armed with firearms, opened fire upon the police, who were unarmed at this time, and the civilians who had to retreat. The civilians returned, pushing the unionist mob back into Antigua Street and Ewart’s Row. This is not how this incident was reported by the police at the inquest for the victims and does contradict the police evidence. The police stated that they did not see any unionist mob and blamed the residents for invading Antigua Street for no reason. This was to cover up their inability to adequately police the situation and in so doing were happy to blame the residents and victims.

The attack seems to have been premeditated, well planned, and not just the usual headlong rush of a mob fortified with alcohol. Snipers, who were positioned on a roof top, had apparent military experience and good rifles.[9]

The Marrowbone was already surrounded when the military arrived by armoured truck. The military opened fire but were unable to identify whether they hit anyone or not or even who they were shooting at. The unionist mob was observed waving a Union flag following behind the armoured car.[10] The military fired on the unionist snipers on the rooftops who slipped back into the safety of their own neighbourhoods. The military remained in the Catholic Marrowbone area patrolling the streets and shooting at suspected Catholic snipers.

At least two of the victims were shot by unionist snipers, who had secured a vantage point close to Glenview Street. Mr Cassidy had just come out of his shop door in Glenpark Street when he was struck by a bullet fired by a sniper on a rooftop and killed instantly. Thomas Toner and Owen Moan were shot dead in the street. Henry Kinney was wounded by a bullet and later died in the Mater Hospital.

The residents took refuge from the gunfire where they could, as the snipers on the roof commanded many of the streets. It took some time for the military to dislodge them from their position. The unionist mob continued throwing stones and occasionally firing revolvers. Their attempts to enter Glenview Street were prevented by the military and police. None of these incidents were mentioned by the police at the inquest for the victims.

The military erected barbed wire barriers across the points separating the two districts. Machine guns on the Oldpark Road were trained down Glenview Street into the Catholic area and at about 4am on Sunday morning things settled down. An armoured car patrolled in the afternoon, barbed wire barricades were erected around the Sacred Heart Church and machine guns were trained on several of the Catholic streets.

It did not look well internationally if Catholic churches were destroyed, as the parochial house in Lisburn had been the previous week. The Catholic residents however, were seen as a threat by the Crown forces. This is likely due to IRA attacks on the military throughout Ireland at the time.

Patrols of locals moved about the district advising the residents to remain indoors and a line of scouts were posted all around the district to give warnings of any further invasions.

At about 2pm Sunday, disturbances broke out at the Crumlin Road end of Ewart’s Row. The unionist mob surged forward and set fire to an off licence on Tennent Street corner. The police and Military with their armoured car drove off the looters. Rioting continued all day. A military picket was set up to protect the neighbouring Catholic district of Ardoyne and the crowds were dispersed. [11]

The Residents’ arrangements for their defence.

Residents of the Marrowbone gathered on the night of 28 August. Their role was to raise the alarm in the event of any incursion into the area. Look outs were posted around the district and a bugle was sounded to raise the alarm.

The three most likely clash points were the corner of Ewart’s Row and Antigua Street, the corner of Glenpark Street and Louisa Street, and the corner of Glenview Street and the Old Park Road next to the Chapel. A particular risk was losing the corner at Glenpark Street and Louisa Street, as that would expose those in Antigua Street to attack from behind. A break in the defences at any of these points would enable unrestricted access to the whole of the Marrowbone area. The logical conclusion being, the residents if they survived, turned out on the road with hundreds of others, their homes robbed and destroyed.

Some of those attempting to defend the area were members of the IRA or the Fianna, some were Hibernians and others ex-servicemen in the British Army.

It is not clear who all the organisations were, involved in planning of these defences. It is probable that almost every able-bodied man and women resident available, including armed IRA and Ancient Order of Hibernian members participated. Fianna members John Murray and Jack McNally took part, according to their later claims to the Free State Military Pensions Board as did IRA Volunteer Owen Moan.[12]

British army ex-service men were also engaged in defending the district. Thomas Henry McCallan of 55 Gracehill Street, originally from Carrickmore, County Tyrone, submitted a witness statement to the Military Pensions Branch in support of Mr Murray’s application. It states that he, assisted by a number of ex- servicemen, had to defend their homes against ‘(a) the so called police, (b) the military, and (c) the orange mob’. In doing so he received an injury to his eye from a bayonet.[13] There could not, however, have been many arms available or there would have been some unionist fatalities during the rioting.

At the same time of raising the alarm the residents were to extinguish the street lamps. They would know their way around in the dark, where all the holes in the walls were, all the entry and exit points, where the broken paving stones were stored for use as missiles and any open houses etc. This would give the residents a slight advantage.

RIC constables Richard Evans and John Reilly of Leopold Street barracks were on duty at Glenpark Street about 11:00 pm. They were less than effective at policing the situation due to a lack of numbers, foresight and planning.

They tried to get the residents, who had no faith in the RIC’s abilities, to disperse. Half the group moved off up Glenpark Street towards Ardilea Street while some remained on watch at the corner. At about 1:00am the alarm was raised, the area was under attack as anticipated. The residents at the Ardilea Street end of Glenpark Street rushed down Saunderson Street into Antigua Street pushing the unionist mob back and smashed the street lamps with rocks. The Street lamp at the top of Ewart’s row was not destroyed and remained burning. This enabled the residents to clearly see those invading their district.

Significantly there were no unionist fatalities in this district on the night of 28/08/1920 and the early hours of 29/08/1920.

The Inquest

The inquest held 8th September 1920, was all about the military and police justifying their actions on the night. Only evidence that supported their story was submitted in order to control the outcome. Police evidence of how the disturbances started were contradictory.

Witnesses from the locality were reluctant to come forward for fear of reprisals given the anti-Catholicism of the authorities. The coroner was Dr Graham and Mr Cecil Fforde, K.C. appeared for the military and police. The inquest did not identify who shot the victims but did conclude that the security forces shooting was justified.

Constable John Reilly gave evidence at the inquest that shortly after 1am stones were being thrown by both sides, from Ewart’s Row and from Antigua Street. He also stated that there were stones coming from Louise Street into Glenpark Street and the crowd in Glenpark Street were throwing stones in return. Shortly after, revolver fire was constant and a bugle was sounded. This does not fit well with the evidence of Head-Constable P. Clarke.

Only evidence that supported the Police’s story was submitted in order to control the outcome at the Inquest. Police evidence of how the disturbances started were contradictory.

Head-Constable P. Clarke gave evidence that at 12:55am on 28th August he passed the corner of Louisa Street and Glenpark Street and everything in the locality appeared to be very peaceful. He made no mention of, and seemed to be completely unaware of, the earlier events throughout the day. Head-Constable P. Clarke along with a sergeant and eight constables returned to the scene from Ewart’s Row after 1:15 am. It was evident that there were two large opposing forces engaged in a deadly conflict. He ordered his party to draw their batons and charge the rioters. Amazingly, it would seem, he was able to make his way through the Unionist mob in Ewart’s Row, identified by Constable J Reilly.

He and his men managed to get to the junction of Antigua Street and Saunderson Street in the nationalist area before they were allegedly, stopped in their tracks by revolver fire. This would indicate that the residents were armed. Still, he made no mention of the unionist mobs in Antigua Street and Louisa Street as reported by Constable Reilly. These unionist mobs must have been obvious. Residents reported these mobs waving union flags. [14]

The fact that he reported, that he had not seen any Unionist mob, excuses why he did nothing about them. Nor did he see them firing revolvers, such as the one that killed John Murray even though he was there at the time. Waving a union flag apparently gave some protection to unionists from the police and military who may have been uncomfortable opening fire on people carrying the same flag which they swore allegiance to.

By this time Head-Constable P. Clarke had been joined by Constables Evans and Reilly making twelve RIC officers in all. Head-Constable Clarke then sent some of his men back to the barracks for their carbines. They then fired a couple of rounds from their carbines to scare off the Catholic rioters. At this time a military armoured car arrived and took up the firing. There was also rifle firing from the direction of the Old Park Road.

Head-Constable Clarke gave evidence that the lamps in the locality were all extinguished and he could see nothing. Therefore, the shooting from the police could only be described as indiscriminate. They were not able to identify the individuals they were shooting at or even if they hit anyone. It is entirely possible this resulted in the deaths of some of the victims.

Constable Richard Evans gave evidence that there was a large agitated crowd in Glenpark Street from 11:00 pm to 1:00am. This contradicts the Head Constables evidence when he stated, all was quiet at 12:55pm. Constable Evans stated that the rioters from the Marrowbone were unopposed. This was contradicted by constable Reilly who stated that he saw stones coming from the direction of Ewart’s Row. Head-Constable P. Clarke gave evidence that when he returned to the scene from Ewart’s Row, after 1:15 am, it was evident that there were two large opposing forces engaged in a deadly conflict. This contradictory evidence cannot be reconciled.

The next to give evidence was Lieutenant Desmond Martin Fitzgerald, 1st Batt. Norfolk Regt. His evidence was that he arrived at the corner of Glenpark Street and Antigua Street in his armoured car. He fired a burst of fire from a Hotchkiss machine gun up Glenpark Street. He drove around the area of the ”Bone” in his armoured car and fired occasionally in the direction that he thought sniping was coming from. He did not know what the result of the firing was and returned to barracks about 10 a.m.

The actions of the military that night could only be described as patrolling the streets of the Catholic Marrowbone district, that were shrouded in complete darkness, during which time they shot indiscriminately at the residents. It is unclear who shot who, but the majority of the victims were likely killed by the military and RIC, who admitted firing when it was too dark to see clearly, as well as by unionist snipers. The police and military claimed that they did not know if they actually hit anyone. At an inquest on 10th September 1920 the city coroner Dr James Graham said, he did not think it was duty of the court to go into the question of who shot every victim. If they did, they would not conclude the investigation in a year.

Some of the victims were shot by the unionist mob, one before the military arrived. The significance of this is that the Catholic Marrowbone district was under fire from unionist mobs, the police and the military from both ends of Glenview Street, Antigua Street and the rooftops.[15] Undoubtedly the security forces contributed to the number of victims.

It is likely that many of the victims were shot by the police and army.

There is no evidence to suggest that any of the victims were involved in anything beyond attempting to defend their area. All the victims were shot in their own Catholic district of the Marrowbone and within yards of their own front doors. There is no evidence that any of the victims ever left their own district. None of the victims were reported to have committed any offence.

Mr Fforde K.C. addressing the jury for another inquest on 10th September 1920 said, 28 cases had been investigated, and that in all the cases it was gratifying to find that the juries came to the conclusion that the deaths which occurred were mainly accidental. He went on to say that he did not think that any of the 28 persons upon the evidence, could have been held to have taken part in the riots. He also admitted, that in a number of cases the deceased were killed by military fire, and in a small percentage of cases they were killed by civilians.[16] This was two days after the inquest for the Marrowbone men.

The rioting ceased about 3 am and started again at 6:30pm. A curfew was introduced between the hours of 10:30 p.m. and 5am, across the city of Belfast and came into force 12 noon Tuesday 31st August.

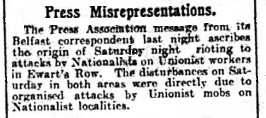

News coverage – Victim Blaming.

In their attempt to justify their actions, the military and police aided by the friendly press, again made victims of these men. The following article appeared in the Irish News Monday August 30th 1920.

In their attempt to justify their actions, the military and police aided by the friendly press, again made victims of these men. The following article appeared in the Irish News Monday August 30th 1920.

The local unionist media lost no time in blaming the local Catholic residents for instigating the events of 29th August. Father John Hassan had the following to say about the victim blaming antics, of the unionist press. – “They have immense advantages on their side in trying to cloak their guilt or even transfer it to their victims. The Press is their great weapon; for no judicial inquiries have been held, and the Belfast government have clearly made up their minds that none shall be made. The Orange party have three strong daily newspapers, with a wide local and considerable overseas circulation. The Catholics of Belfast have been cruelly handicapped in this matter of press propaganda”.[17]

The Irish Times began their coverage of these incidents by stating that the origin of the outbreak in that area is somewhat obscure, [The Irish Times, 30 August 1920] and then went on to regurgitate the official unionist line. The Irish Times owned by the Arnott Family was a staunchly unionist paper and hung on to this stance after independence. John Edward Healy, editor 1907-1934, was a staunch unionist. The paper’s unionist ethos was at its strongest under Healy, and this left the paper with a legacy that it found difficult to shake off.[18]

It is inconceivable that the Catholics of the Marrowbone in their vulnerable location would expose themselves to the wrath of the surrounding unionist majority by invading their areas. The Marrowbone district, a small Catholic enclave of little over a thousand in the midst of a surrounding Protestant population of at least forty to one.[19]

Only those with a knowledge of the geography of Belfast and North Belfast in particular, were able to read between the lines of the Unionist press and distinguish the aggressor from the victim.

The Victims

John Leo Murray, 19 years old, of 11 Glenview Street, Killed at Glenpark Street. John was the eldest of five children of John and Elizabeth Murry. They are recorded as living in Glenview Street in 1911. John Leo’s mother Elizabeth was born in Moneyglass, County Antrim. Elizabeth gave evidence at the Inquest that at 1:30am bugles sounded in the street and the doors were rapped to alert the neighbours that their homes were about to be attacked. John Murray left his house to defend his home, going in the direction of Glenpark Street.

His mother saw his dead body sometime later in a neighbour’s house. William Murray the younger brother of the deceased stated that at 1.30am he was standing at the corner of Gracehill Street and Glenview Street and was looking towards Lebanon Street, off Louisa Street. The deceased was on the footpath some eight feet away.

The Military at this time had not yet arrived on the scene. There was a loud report of a shot from the direction of Ewart’s Row or Louisa Street, and his brother John fell on his back and never spoke again. William ran to him and pulled him into an entry off Glenpark Street. A priest arrived on the scene and the body was brought to a Mrs Brown’s house. Mr Cecil Fforde, K.C. appearing for the military and police stated, “that shot obviously came from the crowd”. The military had not arrived at the time. [20]

John had a ticket for the boat to America in his pocket when he was shot. His brother William made use of the booking, traveling to America in John’s place, where he met and married a woman from Newry. He eventually returned to Dublin where he started a successful construction company and raised his family. His family still live in Dublin to date.

John Murray a nineteen year-old member of Fianna Éireann, A Company, 2nd Battalion, Belfast Brigade from October 1919, then known as the Willie Orr Sluagh.died on 29 August 1920 after he was injured while engaged in defending the civilian population in the Ardoyne area of Belfast during an attack by Government forces.[21]

John’s father made a pension application to the Free State government under the Army Pensions Acts. His application was unsuccessful as one of the witnesses to his service (Sean McNally) was in Crumlin Road Prison, detained under the ‘Special Powers Act’ and was unable to complete the necessary forms on time. (DP11172)

John was awarded the 1917-1921 Service Medal, (the Black and Tan) posthumously. The family received the medal in 2022. His name is inscribed on County Antrim Memorial, Milltown cemetery and states he died on active service. The family were denied the ‘Comrac Bar’ to the medal as the paperwork was not completed on time.

Owen Moan, 47 years old, 36 Glenview Street, was shot in the heart. He was dead upon arrival at hospital. Owen was born near Dromara in County Down and his wife Jane was born in Bellridge, County Kildare. Owen married Jane Nugent 11/10/1893 in the Sacred Heart Chapel, Belfast. They were both 19 years old when they married. At the time of their marriage Owen was living in 22 Glenpark Street and Jane was living in 25 Glenpark Street. In 1901 they were living in 44.1 Mayfair Street, Belfast with their two daughters Catherine and Margaret. Margaret Moan was living at 36 Glenview Street when she married David Campbell in the Sacred Heart Church on 10th October 1934. Owen Moan’s wife made a pension application to the Free State government under the Army Pensions Acts, claiming he had been an IRA volunteer. Her claim was rejected as it was sent in after the closing date. (MSPC;DP4303)

Thomas Toner, 19 years old labourer, 89 Ardilea Street was shot in the neck. He was dead upon arrival at hospital. Killed at Glenpark Street at 1:30am. Thomas was the fourth of five sons of Joseph and Sarah Toner. In 1901 the family were living in 46 Ardilea Street, Belfast and by 1911 they were living in 86 Ardilea Street. Joseph was a widower and his mother, Thomas’s grandmother Margaret Toner, was living with them. Thomas Toner’s father made a pension application to the Free State government under the Army Pensions Acts, claiming he had been an IRA volunteer. His application was rejected as it was sent in after the closing date. (MSPC;DP6741)

Henry Kinney, 48 years old, of 120 Ardilea Street. He was shot in the lung. In 1911 Henry was living with his wife Elizabeth and six year old son John in Ardilea Street. Henry was a packer in a flax mill and his wife was a reeler in a flax mill. Henry Kinney (32) married Elizabeth Mulholland (27) in Holy Cross Chapel Ardoyne 3rd April 1904. His address at the time of his marriage was 122 Butler St and Elizabeth’s was 46 Flax St.

William John Cassidy, 25 years old, 42 Glenpark Street, the eldest child of John and Ellen Cassidy. William was shot through the chest. Mr Cassidy had just come out to his shop door in Glenpark Street when he was struck by a bullet and killed instantly. William was born 9th April 1894 in Trillick, Buncrana, Co Donegal. His parents were John (a farmer) and Ellen Cassidy née McLaughlin. William is buried in the family grave at St. Mary’s Chapel, Cockhill, Fahan Lower, Buncranna, Co. Donegal.

John Charles O’Neill aged 40 of 9 Glenpark Street, a married man who worked as a labourer was shot in the chest 29th August. He was taken to the hospital where it was found that it was lodged in his lung. An operation was performed immediately and the bullet was removed. John Charles O’Neill died 10th September 1920.

John Charles O’Neill (24) married Anne Jane Marley (22) in the Sacred Heart Chapel on 23rd April 1905. His address at the time of his marriage was 22 Glenpark St and Anne’s was 12 Antigua St. His father was Patrick O’Neill a shopkeeper and her father was Michael Marley a labourer. John is recorded as living with his wife Anne Jane and their son Thomas Owen in Glenpark Street in 1911. Ann Jane was born in Portadown, County Armagh. They had the following children; Patrick 10th August 1907- 17th November 1908, Thomas Owen 25th December 1908 – Michael 27th June 1910- 2nd April 1911, Francis 17th May 1912- Twins Marion and Henry were born 16th February 1920. Marion lived for six weeks and Henry for seven months.[22]

A Tragic Chronology.

Marion died 29th March 1920. Her father, John Charles O’Neill, was shot 29th August 1920. He died 10th September 1920. Henry died 27th September 1920. That day while the child was being waked, the Marrowbone district came under attack from the unionist mobs. (an incident referred to the Second Battle for the Marrowbone). Shots were fired through the windows of the wake house. Mrs O’Neill took up the corpse from the bed and in fear for her life, fled out the back of the house and through the streets to safety.

Such was the struggle for survival in the Marrowbone of 1920. The press also listed seven men from the area wounded by gunshots. See appendix.

These men have not received the recognition they deserve. The Catholics of the Marrowbone, and the North of Ireland generally, by necessity, kept their heads down against a background of sectarian violence and discrimination. To do otherwise was to risk discrimination, loss of employment, and ultimately, their lives.

The first ‘battle of the Marrowbone’ was followed by at least three more major clashes in the area, interspersed with skirmishes. At least 13 more people were killed and dozens more wounded in the district.

The first ‘battle of the Marrowbone’ was followed by at least three more major clashes in the area, interspersed with skirmishes. The second major clash or ‘battle’ of the Marrowbone occurred on 28th September 1920. Fred Blair, a Protestant of 69 Louisa Street was shot by security forces during the riot. It was followed by another street battle at Marrowbone on 16th October 1920 when three Protestants were killed in the Marrowbone area during riots. John Gibson (55), of Byron Place and William L Mitchell (25), of 20 Downing Street were shot and Matthew McMaster (34), of Conlig Street was run down by an armoured car in the Marrowbone area during this riot.

The fourth and last large scale clash in Marrowbone in the period, took place from 17th to the 18th April 1922. James Fearon (56) a Catholic, of 22 Glenpark Street and William Johnston (27) a Protestant, 100 Louisa Street, were killed. Annie McAuley (24), 18 Glenpark Street, was shot 17th April 1922 and died 29th April. James Smith (14), Mayfair Street, was shot 18th April 1922 and died 11th May.[23] There were seventeen seriously wounded during this invasion of the Marrowbone area on that occasion and Antigua Street and Saunderson Street were also burned out.

In addition to the lives lost in the four large ‘battles’, in the Marrowbone at least five other lives were also lost in the district. (See below [24] [25] [26] )

The story of the Marrowbone during the Pogrom years is a story of remarkable community spirit and how people come together to support each other through injustice and prejudice. It was also a model of how oppressed communities can open their hearts and homes to protect people fleeing from sectarianism in other areas of Belfast. The tiny district known as the Marrowbone was a haven to many.

Appendix

The Wounded from the night of the first battle.

A local newspaper, The Irish News (Monday 30th August 1920), printed a list of the wounded.

| NAME | ADDRESS | INJURIES |

| P McGrane | 80 Gracehill Street | Bullet wound to leg |

| Alex Kane | Parkview Street | Scalp wound |

| Joseph Charleton | Glenview Street | Gunshot wounds |

These men named above, were all from the Marrowbone area. The next four men named are all from the neighbouring Catholic enclave of Ardoyne.

| NAME | ADDRESS | INJURIES |

| Thomas Foster | 7 Brookfield Street | Bullet wounds to hand and thigh |

| Michael Tobin (21) | 30 Flax Street | Bullet wound to thigh |

| Patrick McCloskey (52) | 56 Herbert Street | Scalp wounds caused by baton |

| Michael Toman | Flax Street | Gunshot wounds |

Notes

[1] Glennon, Kieran, The Dead of the Belfast Pogrom-Counting the Cost of the Revolutionary Period, 1920-22 https://www.theirishstory.com/2020/10/27/the-dead-of-the-belfast-pogrom-counting-the-cost-of-the-revolutionary-period-1920-22/

[2] Feeney Brian, ANTRIM, The Irish revolution, 1912-23, page 74.

[3] Feeney Brian, ANTRIM, The Irish revolution, 1912-23, pages 60-62.

[4] Feeney Brian, ANTRIM, The Irish revolution, 1912-23, page 63.

[5] The quote on so-called police etc is from John Leo Murray Military Service Pensions Collection, DP11172. For the events in Dromore and Lisburn, see Lawlor, Pearse, THE BURNINGS 1920, page 91.

[6] Belfast News-Letter, Thursday, 22nd July 1920, page 5, Re the wounded, The Irish News, Thursday, 22nd July 1920, page 5, Re The Mackie’s worker who was killed, Henry Hennessy, Parkinson, Alan F, Belfast’s Unholy War, page 52

[7] Lawlor, Pearse, THE BURNINGS 1920, page 152.

[8] The Irish News, Monday August 30th 1920, page 5.

[9] Feeney, Brian, ANTRIM, The Irish revolution, 1912-23, page 74.

[10] The Irish News, Monday August 30th 1920, page 5.

[11] The Irish News, Monday August 30th 1920, page 5.

[12] John Murray, Military Service Pensions collection (MSPC) 2RBSD107, Own Moan’s widow’s application, DP4303

[13] John Leo Murray Military Service Pensions Collection, DP11172.

[14] The Irish News, Monday August 30th 1920, page 5.

[15] Parkinson, Alan F, Belfast’s Unholy War, page 67.

[16] The Irish News, Saturday 11th September 1920, page 3.

[17] Kenna, G.B, (Fr J. Hassan), Facts and Figures of the BELFAST POGROM 1920-1922, page 46.

[18] O’Brien, Mark, THE IRISH TIMES , A History, page 37.

[19] Kenna, G.B, (Fr J. Hassan), Facts and Figures of the BELFAST POGROM 1920-1922, page 41.

[20] The Irish News, Thursday September 9th 1920, page 3.

[21] Hay, Marnie, NA FIANNA ÉIREANN and the Irish Revolution, 1909-1923, page 80.

[22] Department of Culture, Heritage and the Gaeltacht, “Civil Records,” database with images, IrishGenology.ie. Indexes of the Civil Registers (GRO) of Births, Deaths Civil Partnerships and Marriages. – National Archive: Census of Ireland 1911: census.nationalarchives.ie.

[23] Belfast News Letter, 2nd June 1922, page 5.

[24] 14th December 1921, Michael Crudden, Oldpark Road, shot in Glenview Street Parkinson , Alan F, Belfast’s Unholy War page175.

[25]27th December 1921, David Morrison, 27 Mayfair Street a Catholic shot dead by ‘B’ Specials. (MSPC; 1D168). 13th January 1922, Joseph Burns (16), 37 Parkview Street, member of Na Fianna shot accidentally. (MSPC; DP934) 12th May 1922, Michael Cullen (44) a Catholic was shot dead in the Bone district by a four strong gang who had asked him his religion. Parkinson , Alan F, Belfast’s Unholy War page 258 –Jim McDermott, Northern Divisions, The Old IRA and the Belfast Pogroms (2001), page 223.

[26] 26th May 1922, William Toal (17) a Catholic, of 42 Mayfair Street shot in the Marrowbone area died on this day. Kenna, G.B, (Fr J. Hassan), Facts and Figures of the BELFAST POGROM 1920-1922, pages 161-171. – Parkinson (2004) page 260. Also MSP- DP6722.