Today in Irish History – 21st July 1920: The Start of the “Belfast Pogrom”

By Kieran Glennon.

In the middle of July 1920, thousands of “disloyal” workers in Belfast were driven out of their workplaces by unionist mobs. In the immediate aftermath, rioting between nationalists and unionists left nineteen people dead.

But this outbreak marked the start of a prolonged period of savage political violence that left almost five hundred dead and which became known by nationalists as “the Belfast pogrom.”

By the middle of 1920, Ulster unionism felt threatened by three separate though related sets of developments.

Class tensions

The first was an increase in trade union militancy that had begun after the end of the Great War in response to the post-war recession. This, coupled with alarm at the growing support across Europe for Russian-style Bolshevism, led to the formation in June 1918 by leading Unionist politicians of the Ulster Unionist Labour Association (UULA).

Their objective was to maintain the cross-class unity on which unionism depended: “The UULA was designed to counter working-class independence of a secular kind, the greatly-strengthened trade union and labour movement, since this threatened unionist solidarity.” [1]

Initially, this strategy seemed to be bearing fruit when three UULA candidates were elected as MPs in the December 1918 General Election. However, just over a month later, the limitations of the UULA strategy were exposed by a huge strike in Belfast.

By the middle of 1920, Ulster unionism felt threatened by class conflict, IRA violence and nationalist electoral advances.

Prior to and during the war, a 54-hour working week had been the norm in the engineering and shipbuilding industries. After the war, unions began to negotiate for a reduction in hours, and employers offered a 47-hour week to begin from January 1919, but the Belfast unions demanded a 44-hour week.

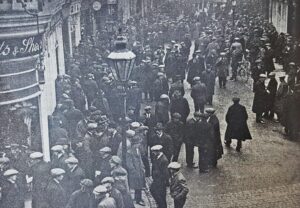

On 25th January 1919, roughly 40,000 workers in the two Belfast shipyards and the main engineering firms went on strike. The strike committee assumed joint responsibility with the municipal authorities for the provision of electricity, gas and water. Tram drivers joined the strike and bread began to be rationed. Despite military intervention, the strikers continued to hold out until 17th February but then some began drifting back to work; by the 24th, the strike had finally been defeated.

However, the spirit of working-class militancy that had prompted the strike remained strong and a march of 100,000 was held to the city’s Ormeau Park on the following May Day. [2]

Electoral reversals

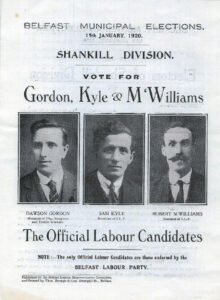

The same spirit was still evident by the time of the municipal local elections which were held on 15th January 1920. In the election to Belfast Corporation, the Unionist Party retained its majority but while the UULA won six seats, ten Belfast Labour Party and two Independent Labour candidates were elected.

Thus, the combined Labour representation was double that of the UULA and even exceeded that of the Nationalist Party and Sinn Féin combined – each of them had won five seats. [3]

However, it was elections elsewhere which prompted consternation among unionism.

For the first time, control of Derry Corporation fell into nationalist hands when only nineteen Unionists were elected, as opposed to ten Nationalist Party, ten Sinn Féin and one Independent Nationalist. The Independent Nationalist, Hugh C. O’Doherty, became the first Catholic mayor of the city since 1688. [4]

In the local elections of 1920, nationalists took Derry city Corporation and the unionist vote in Belfast was split by labour candidates.

The elections for rural and county councils were held on 12th June. An alliance of Nationalists and Sinn Féin retained control of Fermanagh County Council, but a similar alliance won control of Tyrone County Council for the first time. Although the Unionist Party retained control of the County Councils in Antrim, Armagh, Down and Derry, “Both sides of northern nationalism were jubilant at what they regarded as irrefutable evidence of the unworkability of partition.” [5]

Unionism was far less jubilant.

IRA violence encroaches on the north

The final source of concern for unionism was that the violence of what it viewed as the “Sinn Féin rebellion” was no longer confined to the south and west of Ireland, but from early 1920, was gradually encroaching on the north as well.

The IRA attacked RIC barracks in Ballynahinch, Co. Down in February, and in both Crossgar, Co. Down and Cookstown Co. Tyrone in June. [6]

At Easter, in parallel with other IRA units performing similar actions across the country, the Belfast Brigade burned the Custom House and income tax offices in Ann St, North St and Donegall Square on 5th April. [7] RIC officers were killed in Derry in May and in south Armagh in June. [8]

IRA violence spread to the north in the summer of 1920.

Between 20th – 24th June, Derry experienced the most intense violence yet seen in the north, as rival groups of IRA and UVF gunmen fought sniping duels and killed civilian opponents. Altogether, twenty people were killed in Derry during this period. [9]

This series of violent outbreaks culminated on the very doorstep of unionism when, on 2nd July, Head Constable Samuel Perrott became the first policeman to die from political violence within Belfast itself; he had been injured during rioting by loyalists in the Sandy Row area several days previously. [10]

Carson lights the fuse

If labour unrest, electoral reversals and IRA violence were the three powder kegs which unionism faced, Carson lit the fuse with a fiery speech at “The Field” in Finaghy, following the annual Orange Order march on 12th July. He told the crowd:

“We must proclaim today clearly that come what will and be the consequences what they may, we in Ulster will tolerate no Sinn Féin – no Sinn Féin organisation, no Sinn Féin methods … But we tell you [the government] this – that if, having offered you our help, you are yourselves unable to protect us from the machinations of Sinn Féin, and you won’t take our help; well then, we tell you that we will take the matter into our own hand …. And these are not mere words. I hate words without action.” [11]

‘Ulster will tolerate no Sinn Féin – no Sinn Féin organisation, no Sinn Féin methods’: Edward Carson.

Republicans were not the only opponents he denounced, as he had not forgotten the impact of the engineering strike the previous year:

“…These men who come forward as the friends of Labour care no more about Labour than does the man in the moon. Their real object, and the real insidious nature of their propaganda is that they mislead and bring about disunity amongst our own people and in the end before we know where we are, we may find ourselves in the same bondage and slavery as is the rest of Ireland in the South and West.” [12]

Carson’s speech set the tone for what was to follow.

Killing of Lieutenant Colonel Smyth

On 19th June, at Listowel barracks, the newly-appointed RIC Divisional Commissioner for Munster, Lieutenant Colonel Gerald Bryce Ferguson Smyth, had made an inflammatory speech in which he called on policemen to adopt a shoot-to-kill policy:

“They [the RIC] are not to confine themselves to the main roads but take across country, lie in ambush, take cover behind fences, near the roads, and, when civilians are seen approaching, shout ‘hands up’. Should the order be not immediately obeyed, shoot, and shoot with effect. If the persons approaching carry their hands in their pockets or are in any way suspicious looking, shoot them down. You may make mistakes occasionally and innocent persons may be shot, but this cannot be helped and you are bound to get the right persons sometimes. The more you shoot, the better I will like you, and I assure you that no policeman will get into trouble for shooting any man.” [13]

The immediate effect of the speech was to prompt a police mutiny, but it also made Smyth a marked man in the eyes of the IRA. On 17th July they tracked him to the Country Club in Cork city, where they killed him.

The immediate spark for the violence in Belfast was the IRA assassination of RIC officer Gerald Smyth in Cork.

As his parents were natives of Banbridge, County Down, his body was sent north for burial, although railwaymen initially refused to transport it. A special train was laid on to bring mourners from Belfast to Banbridge.

His funeral on the afternoon of 21st July sparked an eruption of sectarian violence in Banbridge. The day after the funeral, a mob of over 2,000 loyalists went around the local linen mills, chasing Catholics from their jobs; Smyth’s mother announced that the family’s two mills would no longer employ Catholics.

Over the next couple of days, Catholic-owned pubs and businesses were looted and burned and eighteen Catholic families saw their homes fully or partially burned. The RIC either could not or would not stop the loyalist mob and order was only restored with the arrival of a detachment of British troops two days later. [14]

Expulsions

Belfast had two shipyards: Harland & Wolff was the larger and more famous, while Workman Clark was known as “the wee yard.” The workforces of both were due to return from the annual “Twelfth” holiday on 21st July, the same day that Smyth was to be buried in Banbridge.

Belfast had two shipyards: Harland & Wolff was the larger and more famous, while Workman Clark was known as “the wee yard.” The workforces of both were due to return from the annual “Twelfth” holiday on 21st July, the same day that Smyth was to be buried in Banbridge.

That morning, the Belfast Protestant Association (BPA) posted notices in both shipyards, calling for a meeting of “all Unionist and Protestant workers of the shipyards” to be held at 1:30pm outside the wee yard. About 5,000 workers attended and moved a resolution demanding the expulsion of all “non-loyal” workers. [15]

By 3:30pm, a mob had arrived outside Harland & Wolff, the gates of which had been shut:

“The gates were smashed down with sledges, the vests and shirts of those at work were torn open to see if the men were wearing Catholic emblems, and then woe betide the man that was. One man was set upon, thrown into the dock, had to swim the Musgrave Channel, and having been pelted with rivets, had to swim 2 or 3 miles, to emerge in streams of blood and rush to the police in a nude state.” [16]

While the most enthusiastic perpetrators of the expulsions were the craftsmen’s apprentices, prominent members of the UULA were among the leaders. [17]

The next day, the BPA turned its attention to some of the other prominent employers across Belfast: “disloyal” workers were expelled from the Sirocco Works in Ballymacarrett, Mackie’s Engineering on Springfield Road, Gallagher’s Tobacco in York St, Combe Barbour, Musgraves and many linen mills.

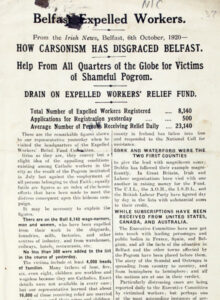

Loyalists forcibly expelled 7,500 workers from the Belfast shipyards, including nearly 6,000 Catholics and 1,800 Protestant left wing activists.

Altogether, nearly 7,500 workers were expelled from their workplaces. While Catholics constituted the majority, this number included roughly 1,850 Protestants – these were the so-called “rotten prods”, trade unionists and socialists, who were adjudged to be equally as disloyal as Catholics and “Sinn Féiners”; one of them, James Baird later told a conference of the Trade Union Congress:

“Every man who was prominently known in the labour movement, who was known as an I.L.P.-eer [Independent Labour Party] was expelled from his work just the same as the rebel Sinn Feiners. To show their love of the I.L.P. they burnt our hall in North Belfast … The district chairman of the AEU, a very moderate and quiet Labour man, was beaten not once but two or three times because he persisted in returning to his work.” [18]

Violence

News of the expulsion of Catholics from the shipyards spread quickly among their co-religionists and that evening, the remaining shipyard workers were attacked as they made their way home.

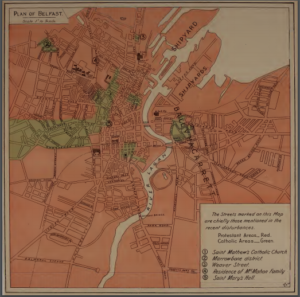

Trams were attacked first in Short Strand in the east of the city and the violence soon spread across the River Lagan as the trams made their way across the Albert Bridge and through the nationalist Market area, where they were stoned.

A rival loyalist mob formed in nearby Donegall Pass and soon a full-scale riot was in progress, with the police baton-charging both sides. [19]

A Catholic woman, Margaret Noade, who had left her home in Ballymacarrett to visit her sick mother in the Market, was shot and killed by a policeman as she turned a corner into Verner St. [20]

Elsewhere in the city, when trams carrying Protestant shipyard workers home to the Shankill arrived, trouble quickly broke out in the streets between there and the nationalist Clonard district. The British military was called on to restore order and, a short distance away, they shot and killed two Catholics, one on the Falls Road, one just off it. [21]

The level of violence increased the next day, as the expulsions spread to workplaces beyond the shipyards – three people had been killed on the 21st, but nine more died on the 22nd.

Once word of the shipyard expulsions reached the rest of the city, rioting broke out between Catholics and Protestants, leading to the British military being called out.

All but one of these killings took place in Clonard, where once again the military were called on to separate the rival rioters. However, several of these deaths were surrounded in controversy: four Protestant men were killed, two each in Kashmir Road and Cupar Street, but the military denied that they had fired into those streets. [22]

Other military statements were refuted in the investigation into the death of Brother Michael Morgan, one of the monks in Clonard Monastery, who was killed the same night by a burst of fire from a Lewis gun. Initially, the military claimed they had been shot at from the monastery itself and were simply returning fire.

That version of events was contradicted at the inquest into Br Morgan’s death, when “District-Inspector Attridge said that on the invitation of the Rector of the Monastery he visited the building, but could find no trace of recent firing from the building or any sign of firearms.” [23]

Trouble also erupted again on the 22nd in the east of the city. Among the few trades dominated by Catholics in Belfast were those of publican and spirit grocer and over the course of this period, three-quarters of the spirit groceries in Ballymacarrett were damaged and many looted.

On the evening of the 22nd, a loyalist mob attacked St Matthew’s Catholic church on the Newtownards Road; attempts were made to burn the Cross & Passion convent beside the church and the attackers were only driven off when a detachment of British troops arrived and opened fire. Over the next few days, two of those shot by the soldiers would subsequently die. [24]

The following night, St Matthew’s and the convent were again attacked; a detachment of military had been stationed inside the church grounds to protect the buildings and they opened fire on the mob – two Protestants were fatally wounded. [25]

However, over the next few days, a relative peace descended on Ballymacarrett, due in no small part to the efforts of John Redmond, rector of St Patrick’s Church of Ireland parish in the area. He organised a “peace picket” made up of ex-servicemen who acted as vigilantes, intervening to defuse potentially violent incidents. [26]

Armed nationalist response

On the other side of the political / sectarian divide, there is contradictory evidence relating to the provision of armed defence to nationalists.

Seamus McKenna was an IRA officer at the time; he later said:

“… at the beginning the Volunteers were ordered not to take part in what was regarded as fratricidal strife. After a week or two, however, it was obvious that, if the Catholic population were to survive at all, it would be necessary for the Volunteers to protect them in some way, and accordingly the IRA became involved in a struggle against disciplined and undisciplined Orange factions, whilst at the same time having to bear in mind that their main object was to carry out aggressive action against the British forces of occupation.” [27]

However, McKenna’s recollection may have been faulty.

Two of the Catholics killed in Clonard during the first few days after the shipyard expulsions were members of the IRA: Joseph Giles, killed in Bombay St on the 22nd, and John McCartney, who was shot in Kashmir Road on the 22nd and died on the 24th. However, as both were Clonard residents, it is unclear whether or not they were killed while on IRA duty. [28]

The most direct evidence that the IRA were in fact in action is in a sentence in a newspaper report: “Irish Volunteers patrolled the Falls road and urged Nationalists to keep away from the areas in which trouble was raging.” [29]

The IRA attempted to defend Catholic areas and were joined by other nationalist groups such as armed members of the Ancient Order of Hibernians and

They may not have been the only armed nationalists involved. Within northern nationalism, there was a long-standing, bitter rivalry between republicans such as the IRA and Sinn Féin on the one hand, and the nationalist Ancient Order of Hibernians on the other. Roger McCorley later went on to become O/C of the IRA’s Belfast Brigade, but he inadvertently alluded to the presence of armed Hibernians at this time:

“On the outbreak of the pogrom we had got information through our Intelligence that a Catholic clergyman outside Belfast had sixty Martini-Enfield rifles which had been the property of the old National Volunteers who were no longer in existence. He had sent information into Belfast to the Hibernian element that he had these arms and he asked them to call out and collect them for use in the defence of the nationalist areas. The information from our Intelligence Department was such that we were able to call out at the appropriate time and collect these arms ourselves. The clergyman instructed our man, he being under the impression that we were of the Hibernian element, that under no circumstances were these arms to get into the hands of the IRA. Our people assured him that they would make sure no one would get control of the arms other than themselves.” [30]

It can safely be assumed that if the rifles had reached the intended recipients, they would have made use of them for the intended purpose.

The start of a ‘Pogrom’?

Over the course of four days from 21st to 25th July, a total of nineteen people were killed and almost two hundred injured in Belfast; in addition, some of those wounded by gunfire during this period would later succumb to their injuries in the coming weeks.

The dead included nine Protestant and eight Catholic civilians and two members of the IRA. In terms of locality, Clonard and the Falls bore the brunt of the deaths, with thirteen killed; four died in Ballymacarrett and two in the Market.

All but two of the deaths were attributed to British troops, although military responsibility for four killings was disputed. One curiosity of the violence is that for the most part, although the RIC was ordinarily an armed force, unlike police elsewhere in the UK, they were not armed during these disturbances – the solicitor for the RIC and military at the inquests stated:

Over the course of four days from 21 to 25 July 1920, a total of nineteen people were killed and almost two hundred injured in Belfast.

“He also desired to say that the police throughout the whole of these riots [in Clonard] never fired a shot. They had no arms at all except batons. Any firing that was done was done by civilians, and then there was the response by the military to that fire.” [31]

Why the RIC were sent to quell the riots armed only with batons is unclear, but it meant the military was quickly called on to use lethal force to restore order.

Apart from the deaths for which troops were responsible, one woman was killed by an RIC officer and the death of Catholic Henry Hennessy, shot in Kashmir Road on 22nd July is, by consensus, attributed to a Protestant gunman. [32]

Roughly 7,500 Catholics and “rotten prods” were expelled from their workplaces and dozens of people on both sides of the divide were driven from their homes by mobs, in many cases their houses burned after they had fled. Pubs and spirit groceries, mainly Catholic-owned, were attacked and looted.

Did this constitute the start of a pogrom?

The Encyclopaedia Britannica defines a pogrom as “a mob attack, either approved or condoned by authorities, against the persons and property of a religious, racial, or national minority.” The events that began in Belfast on 21st July 1920 fail to meet this definition on two grounds.

The events that began in Belfast on 21 July 1920 fail to meet the definition of a pogrom as the authorities, specifically the military, intervened to stop the violence

The first is that far from condoning the attacks, the authorities – in the form of the military – intervened to stop the violence. Not only that, they did so in a remarkably even-handed, if ruthless, manner: they shot and killed eight Catholics and nine Protestants.

The second way in which the Belfast violence fails to meet the definition of a pogrom is that the initial attacks in the shipyards, as well as those that followed in the other significant industrial workplaces, were not perpetrated on a single religious or national minority – both Catholics and “rotten prods” were the victims.

However, what began with workplace expulsions and nineteen deaths near the end of July 1920 became an enduring horror that would go on to grip the city for over two years and see almost five hundred deaths. By any metric, the minority nationalist community suffered disproportionately from this violence – it was for this reason that they remembered 21st July 1920 as the start of “the Belfast pogrom.”

Kieran Glennon is the author of From Pogrom to Civil War – Tom Glennon and the Belfast IRA. See also, Podcast: Belfast violence 1920-1922 with Kieran Glennon

References

[1] Austen Morgan, Labour and Partition, The Belfast Working Class 1905-23 (London, Pluto Press, 1991), p215

[2] Christopher J. V. Loughlin, Labour and the Politics of Disloyalty in Belfast, 1921-39: The Moral Economy of Loyalty (Cham [Switzerland], Palgrave & Macmillan, 2018), p9

[3] Ian Budge & Cornelius O’Leary, Belfast: Approach to Crisis – A Study of Belfast Politics 1613–1970 (Cham [Switzerland], Palgrave Macmillan, 1973), p139

[4] Adrian Grant, Derry: The Irish Revolution, 1912-23 (Dublin, Four Courts Press, 2018), pp93-4

[5] Éamon Phoenix, Northern Nationalism: Nationalist Politics, Partition and the Catholic Minority in Northern Ireland 1890–1940 (Belfast, Ulster Historical Foundation, 1994), p85

[6] Belfast News Letter, 24th February 1920; Roger McCorley statement, Bureau of Military History (BMH), Military Archives, WS0389; Fergal McCloskey, Tyrone: The Irish Revolution, 1912-23 (Dublin, Four Courts Press, 2014), pp 90-1

[7] Belfast Brigade activity report, Military Service Pensions Collection (MSPC), Military Archives, MA/MSPC/A/48

[8] Grant, Derry: The Irish Revolution, 1912-23, p97; Freeman’s Journal, 7th July 1920

[9] Grant, Derry: The Irish Revolution, 1912-23, pp97-102

[10] Irish Independent, 3rd July 1920

[11] Michael Farrell, Northern Ireland: The Orange State (London, Pluto Press, 1980), pp27-8

[12] ibid, p28

[13] Jeremiah Mee statement, BMH, Military Archives, WS0379

[14] Pearse Lawlor, The Burnings, (Cork, Mercier Press, 2009), pp67–78

[15] Alan Parkinson, Belfast’s Unholy War (Dublin, Four Courts Press, 2004), p33

[16] Farrell, Northern Ireland: The Orange State, p28

[17] Morgan, Labour and Partition, pp270-1

[18] Parkinson, Belfast’s Unholy War, p36

[19] ibid, p42

[20] Belfast News Letter, 3rd August 1920

[21] Irish Independent, 3rd August 1920

[22] Parkinson, Belfast’s Unholy War, p54

[23] Freeman’s Journal, 26th July 1920

[24] Jim McDermott, Northern Divisions – The Old IRA and the Belfast Pogroms 1920–22 (Belfast, Beyond The Pale Publications, 2001), p40

[25] Belfast News Letter, 24th July & 12th August 1920

[26] Parkinson, Belfast’s Unholy War, p46-8

[27] Seamus McKenna statement, BMH, Military Archives, WS1016

[28] McDermott, Northern Divisions, n37 p283; Pension file of David Matthews, MSPC, Military Archives, MSP34Ref60258

[29] Freeman’s Journal, 23rd July 1920; as the IRA were not uniformed, it is likely that the reporter was only able to distinguish them from civilians by the fact that they were armed

[30] Roger McCorley statement, BMH, Military Archives, WS0389

[31] Belfast News Letter, 12th August 1920

[32] Parkinson, Belfast’s Unholy War, p52