Book Review: Recovering an Irish Voice from the American Frontier: The Prose Writings of Eoin Ua Cathail

Edited by Pádraig Fhia Ó Mathúna,

Edited by Pádraig Fhia Ó Mathúna,

Published by: Denton TX: University of North Texas Press, 2021)

Reviewer: Aidan Beatty

John Cahill/Eoin Ua Cathail was born in 1840 in Templeglantine in Limerick, about halfway between Abbeyfeale and Newcastle West. In 1863 he emigrated to the United States, after which he led a relatively interesting life, serving in the US military (though probably never seeing direct military engagement) and spending three years as a police-officer in Chicago.

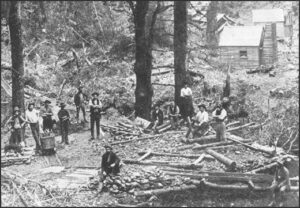

He later lived in Pentwater in northern Michigan, centre for the lumber industry, where Ua Cathail alternated between farming, running a saloon, and involvement in local politics. Sometime after his move to the United States, he developed an awareness of the connections between language and identity and began to write short stories in Irish.

Eoin Ua Cathail wrote a series of short stories, in his native Irish language, based on his life as an immigrant in late 19th century America, later publised by Douglas Hyde.

In the main, these were exaggerated accounts of his adventures in the American West, full of violent encounters with Native Americans and exciting escapes. His fictional self led a far more daring life than his real self.

Ua Cathail began corresponding with Douglas Hyde and some of his stories were published in the Gaelic League’s An Claidheamh Soluis in the early decades of the twentieth century. His earliest story was completed in 1913, by which time he was already seventy-four years old. By the 1920s, Douglas Hyde was making efforts to secure a publisher for a collected edition of Ua Cathail’s work but the effort came to nothing; Hyde wrote to Ua Cathail in 1928 to confess ‘ní fheicim aon chlódhadóir d’iomchóradh an cosdas é féin’ [I don’t see any publisher who would carry the costs] and ‘Bhí súil agam go gcuirfidh na sgéalta i gcló aca, acht theip orm’ [I hoped they would put the stories in print, but I failed]. Ua Cathail died at the end of 1928 and his literary output has remained mostly forgotten.

Pádraig Fhia Ó Mathúna’s edited volume – smartly published in a bilingual edition – collects together a host of Ua Cathail’s stories and also raises important questions about the role that Irish immigrants (or, perhaps more accurately, Irish settlers) played in Manifest Destiny, in the opening up the American interior to white settlement, and in the genocide of Native Americans that went hand-in-hand with all this.

As of 1876, the year of the Battle of Little Big Horn, a third of General Custer’s famous Seventh Cavalry were Irish, a statistic Ó Mathúna provides in a perceptively wide-ranging introductory essay that places Ua Cathail’s prose into the dual contexts of the Irish presence in the American West and the popular accounts of white American settlement in that region.

As Ó Mathúna laments: ‘The spoken Irish of many members of the US military, laborers, settlers, and others along the plains of the West and forests of the Midwest during the nineteenth century has been all but lost to time.’ Ua Cathail’s stories, for all their flights-of-fancy, are a rare souvenir of that Irish-language New World culture.

The first story in the collection, Cuairt air Tecsas [Trip to Texas], is set in 1868 or ’69, after ‘the rebellion’ [an cheannairc, as Ua Cathail calls the American Civil War], and at a time when ‘the Indians broke out, wrecking, violating, and destroying everything before them’, an early expression of Ua Cathail’s settler-colonial worldview.

Ua Cathail served in the US military in the late 1860s, though seems to have exaggerated his role in he wars against the native Americans.

Setting out with other soldiers from Little Rock, Arkansas [Cathair Carraig Bheag, sa Stát Árcansas], Ua Cathail journeys to Texas where he meets with an Irish woman that has married a Native American; he describes her ‘an bhean dubh buídhe’, literally: the black/dark yellow woman. In Ua Cathail’s racialized understanding, she has become Native American [buídhe/yellow] and yet she is also dubh/black, with Ua Cathail being ambiguous as whether he is here referring to her hair colour, as would be the conventional use of colours to describe a person in Irish, or her skin and racial phenotype, as would be more common in American English.

This Irish woman is herself prone to racialised attacks on Native Americans; she denounces ‘the vicious Indians’ [na th-Indiachaibh cosgrach] whilst simultaneously boasting of the two thousand acres of land her family now holds in the US (a larger estate than that of the ‘heinous landlord’ who oppressed her family in Ireland).

That native dispossession and white acquisition of land were two sides of the same settler-colonial coin is left diplomatically unstated. At the same time, the story features an escaped slave who is depicted without any overt racist anti-Black tropes, a switching between racist and non-racist (if never really anti-racist) depictions that defines Ua Cathail’s prose.

In the follow-up piece, Cuairt air Tír na th-Indiachaibh [Trip to Indian Territory], Ua Cathail recounts his travels with various soldiers, one of whom was a ‘Meicsicánó’, using a Gaelicised version of the original Spanish noun [Mexicano]. This linguistic phenomenon – how to render the American experience into Irish – is an interesting sidebar throughout. In a later story, Ua Cathail describes traveling around Lake Michigan on a naobhóg [naomhóg, a Munster Irish term for a currach rowing boat], which Ó Mathúna translates as a canoe.

In Cuairt air Tír na th-Indiachaibh, he recounts how the Native Americans, led by their Chief [taoiseach], outnumber the soldiers but were literally outgunned. Ua Cathai is frank and unemotional in his discussions of ‘the treacherous Indians’ [na th-Indiachaibh fealltach] and how they were slaughtered is written in a disarmingly frank and unemotional tone; he gives the figure of 448 killed and ends by recounting the ‘high praise’ he and the other soldiers received after all this.

In reality, Ua Cathail’s military stint was far less eventful; while the accounts here are inaccurate in the most literal sense, they do still illustrate the real-existing ideologies of white American frontier life.

Imreasán leis na th-Indiachaibh [Conflict with the Indians] is a meandering story and the longest in the collection. It employs standard narrative conceits about a white girl kidnapped by rapacious native enemies and the settlers who bring her home. One slaughter of Native Americans in the story is preceded by Ua Cathail being trapped in a cabin as Indians attempted to break in with their ‘tomahawks’ [tuaghanna, axes].

The subsequent killing of six Native Americans is presented in an oddly perfunctory way; as racialised stock characters lacking individuality, their deaths are devoid of meaning. Later in the story, the violence is lamented but also presented as a kind of ahistorical and apolitical event, a function of the inherent violence of all human beings rather than the product of a specific encounter between colonizers and natives in the context of the post-Louisiana Purchase and post-Civil War expansion of the United States.

The plot of Fuadach Máire Beag Ní Fhloinn ag Mathghamhuin sa mBliadhain 1867, a ngar d’Uisg-Glasda, Misigan [The Abduction of Little Máire Ní Fhloinn by a Bear Near Pentwater, Michigan, in 1867] is self-evident in the unwieldy title.

Pointing to how Native Americans are understood both in Ua Cathail’s stories and in American frontier literature more generally, the bears [na mathghamhna] in this story function like Native Americans; a part of the wilderness and a dangerous threat to settlers.

This story ends with a Peckinpah-type keening for the lost world of the American frontier, replaced now with paved streets and automobiles. Ua Cathail compares it to Cill Chais, referring to the Irish Jacobite lament Caoine Cill Chais, which describes the aftermath of the destruction of Ireland’s forests during the seventeenth century. Though at the same time, Ua Cathail says of Michigan: ‘To tell the truth, it’s like Tír na nÓg’, still a natural cornucopia but with the added bonus that dangerous animals have been exterminated.

A critique of colonial capitalism enters the later stories, but always coupled with a certain awe about the scale of American capitalism and the opportunities it gives to white settlers. Ua Cathail is critical of both environmental degradation and exploitative bosses.

At times, there is a kind of rough frontier equality to the stories, with various settlers of European origin working happily alongside Native Americans; though it is worth observing that they are working in concert in the service of white settlement rather than any kind of shared native-white project.

In several stories, Ua Cathail commends the working of the Homestead Act [Acht an Bhaile] which ‘entitled anyone [sic] over the age of twenty-one to eighty acres of land’. As Ó Mathúna points out, the Act was, in fact, restricted to US citizens who had never taken up arms against the United States. Moreover, it was never extended to Native Americans (who were not eligible for US citizenship until 1924) and in practice was not available to African Americans or Chinese immigrants.

The stories provide a neat encapsulation of a specific moment in the history of Irish migration to North America and of the ways that Irish people engaged with the mythologies of the American frontier

Ó Mathúna ends the collection with three appendices, two of which are of mainly limited biographical relevance; a piece recounting Ua Cathail’s life in America and an appendix on his connections of Douglas Hyde. The third, an untitled editorial on the Spanish American War from a May 1899 issue of An Claidheamh Soluis, is of broader interest. Taking broad swipes at critics of American imperialism in Ireland, Ua Cathail observed that

There are many people in the Old Country slinging insults and criticisms at the Americans. They think that they [the Americans] are going to subjugate the poor people that they freed from Spain’s oppression. They think that the Americans want to oppress every Black man [fear dorcha] under their rule. That is not the case. There is not a people in the world who are more humane, more kind, or more generous than the Americans. I would pray to the God of Mercy every day of my life for a government in Ireland that is as good and as free as the one given by the Americans to the Filipinos [na Filibínigh].

Suffice it to say, the accusations that Ua Cathail sought to refute had more than a ring of truth to them!

Ua Cathail went on to claim ‘I spent a part of my life in the Philippines [Tír na Tagalóga]. I know them well. They are poor, uneducated, and ignorant. They are as mulishly ignorant as the Cubans. It will be fifty years until they are suited – with good instructors – to establish a government under their own care.’

As well being deeply racist, Ó Mathúna points out that Ua Cathail was almost certainly lying about having ever visited the Philippines. This is an unnerving but not all surprising end to this edited collection. Throughout his prose writing, Ua Cathail displayed both a conventional Gaelic Leaguer perception of the Irish language and its inherent national value, as well as an incipient American patriotism common to newly arrived European immigrants.

And racism was central to that latter patriotism. It is debatable if these stories are “good” in any kind of grand literary sense, though their unpretentious style and adventurous storylines as well as Ó Mathúna’s judicious translations into English do make them enjoyable to read.

The stories also provided a neat encapsulation of a specific moment in the history of Irish migration to North America and of the ways that Irish people engaged with the mythologies of the American frontier. And this probably remains the most important historical aspect of Ua Cathail’s writings.