Bloody Sunday 1920 Revisited

By John Dorney

Today, November 21, 2020, is 100 years since the events known as ‘Bloody Sunday’ in Dublin in 1920. Over thirty people lost their lives in a notorious welter of political violence, that made headlines across Ireland and across the world.

The day began with an IRA operation, organised by Michael Collins’ Intelligence Department, that assassinated over a dozen British officers and alleged spies, mostly in their beds, that morning.

Crown forces responded by mounting a joint military and police raid on a Gaelic football match taking place at Croke Park in the north of the city, and once there, they opened fire on the crowd, killing fourteen and injuring another 72.

Over thirty people were killed and nearly 100 injured on Bloody Sunday 1920.

That evening, two the leaders of the IRA Dublin Brigade, Dick McKee and Peadar Clancy, along with a civilian friend, Conor Clune, were killed while prisoners in Dublin Castle, having been arrested the previous day. Dublin was placed under a strict military curfew, under the cover of which, British forces shot and killed several more civilians.

This article will try to answer some of the remaining questions about the day: Why did the IRA mount such a ruthless operation that morning and how successful was it? Why did Crown forces open fire at Croke Park and who was responsible? What happened to the three prisoners at Dublin Castle and those shot after curfew? What political effect did the events of the tragic day have?

‘Them or us?’

The standard republican narrative of the day has it that Bloody Sunday was a last ditch effort by Michael Collins to prevent the decapitation of the top of the IRA by an elite British intelligence squad known as the ‘Cairo Gang’.

This is not inaccurate, in broad strokes, but it simplifies matters a little.

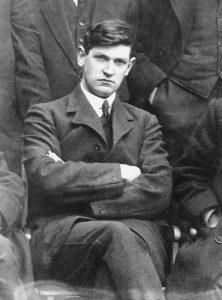

Michael Collins himself, the IRA Director of Intelligence, is usually presented as an elusive mastermind whom the British could not identify. But Collins had already been imprisoned twice by the British, interned at Frongoch in 1916 for his role in the Easter Rising and arrested again in 1918 for a ‘seditious’ election speech in Longford. It seems very strange then, that British intelligence could not identify him in 1920.[1]

Perhaps, though, this was a result of Collins himself having neutralised the Detective arm of the Dublin Metropolitan Police (DMP) by that point. Its most active detectives were killed by Collins’ IRA Intelligence Squad in 1919 and early 1920 and others, such as David Nelligan and Ned Broy had been ‘turned’ to work as double agents for Collins.

It is possible that the Military intelligence operation in Dublin never had access to the DMP’s files on Collins, or that these had been stolen or misplaced by mid 1920, but it seems extraordinary.

Was there a ‘Cairo gang’ of elite spies imported from Egypt?

British Military Intelligence had imported nearly 100 operatives into Dublin by that time and much to the chagrin of Army Intelligence head, John Brind, they were put under the command of Ormonde de Winter, a former artillery officer with no experience of intelligence or espionage. Winter, a personal friend of ‘Chief of Police’ Henry Tudor, reported to Tudor rather than the military authorities, which may also have hampered and confused British intelligence gathering.[2]

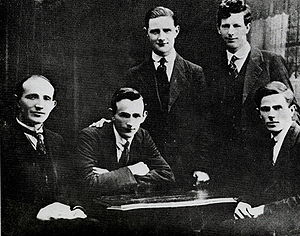

Was this, then, the intelligence officers led by Winter, the ‘Cairo Gang’? In fact the name seems to have been coined by IRA Intelligence officers, Frank Thornton, Tom Cullen and Charles Saurin, who, posing as informers, met a number of British Intelligence officers in the Cairo Cafe on Grafton Street in Dublin city centre.

So the ‘Cairo Gang’ was, in reality an IRA nickname for a British intelligence operation that, in fact, went far beyond the men who frequented the Cairo Cafe. Some of them may have indeed served in Egypt, but they were not a specially imported group of elite spies.

Certainly though, they were beginning to tighten the net around Collins’ operation in late 1920. In October they had cornered and killed Sean Treacy, an IRA gunman from Tipperary, who, along with Dan Breen, Collins had taken to using for ‘jobs’ in Dublin. Breen was also wounded and nearly captured in a safe house in the northern suburb of Drumcondra.

In the meeting at the Cairo Cafe, Cullen, Thorton and Saurin were amazed to hear the officers ask them to locate themselves, as well Liam Tobin, the deputy head of Intelligence, indicating that while British had trouble identifying their suspects by face, they had a very accurate list of names to work off. In a separate incident on November 13, Thornton, Tobin and Cullen were arrested and questioned but let go. [3]

The British just missed arresting Richard Mulcahy, the IRA Chief of Staff, in his secret office on Bachelors Walk on November 10 and seized his papers which included an extensive list of names of IRA members in Dublin. [4]

This was a time when British reprisals throughout Ireland threatened to overwhelm the republican movement. In Dublin too, the British forces were exhibiting a new ruthlessness. In the month of October 1920 alone, the Republican roll of honour ‘The Last Post’ records three Volunteers ‘murdered by British forces’ in Dublin after being taken prisoner. [5]

In early November a young Volunteer, Kevin Barry was hanged for his role in the shooting of three soldiers in Dublin, and just before Bloody Sunday, the Auxiliaries had assassinated a civilian, Peter O’Carroll, father of two Volunteers, calling to his house and shooting him dead.[6] On the night before Bloody Sunday, Dick McKee and Peadar Clancy, heads of the Dublin Brigade were arrested and were ultimately killed.

So Collins’ interpretation that it was ‘them or us’ is certainly plausible.

What it leaves out, though, is the political dimension of the operation. Prime Minister Lloyd George claimed ‘we have murder by the throat’. Bloody Sunday, almost certainly, was also intended as riposte, a ‘spectacular’ to show that the IRA was, in fact, far from being beaten.

The original plans for the day included, as well as killing British intelligence officers, large scale commercial attacks in England, including sabotage and arson at the Liverpool docks, destruction of a power plant in Manchester and a timber yard in London. The English dimension had to be called off after the British discovered the plans among Mulcahy’s papers.[7]

Did they get the right men?

Collins put his Intelligence Department and the Dublin Brigade to work creating a list of targets to be hit. Originally it was envisaged that some 50 men would be killed, but the Dail’s Minister for Defence Cathal Brugha objected to some of the names and eventually the list was pared down to 35, or 20 according to some sources.

It was largely compiled, not by Collins himself, but by his Intelligence officers Frank Thornton and Tom Cullen. Planning of the operation, which involved, we now know, 165 IRA and Cumman na mBan personnel from the Dublin Brigade as well as the Squad, was largely given to Brigade commander Dick McKee and head of 2nd Battalion, Sean Russell. [8]

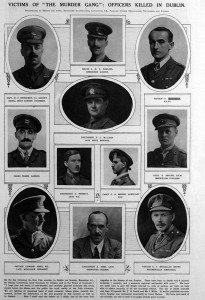

I have written elsewhere for RTE on the morning’s grisly events. In all fourteen men were shot and killed by the IRA. Another four were shot and wounded, but survived, though one died later.

At the time, the IRA were actually disappointed that so many of their targets got away. Some were shot but not killed by nervous gunmen, others, more commonly, were not at the address the IRA ‘visited’. Intelligence officer Charlie Dalton alleged that the men of First Battalion did not carry out any of the raids they were supposed to, along the North Circular Road and in the Phoenix Park.[9]

The IRA were initially disappointed with the results of the operation but British military reported that it ‘temporarily paralyzed the Army Special Branch’

Of those they did kill, nine were serving British Army officers. Six were certainly intelligence officers, one was a staff officer and two were court martial officers. Another, Fitzgerald was a former Army officer, recently transferred to the RIC (though he seems to have been mistaken for another man, Fitzpatrick), and another two were Auxiliaries who happened upon the scene of one of the shootings.

This leaves three civilians; Thomas Smith, a landlord, who was unlucky enough to have been in one of the boarding houses when it was attacked, Patrick McCormack, an off duty Irish British Army officer, of the veterinary corps, who was apparently in Dublin to buy horses and an ‘eccentric civilian’ (another ex officer) Leonard Wilde.[10]

James Cahill, who was involved in shooting Wilde and McCormack at the Gresham Hotel on O’Connell Street, claimed that Wilde, thinking that they were police, told them he was ‘a secret service agent just back from Spain’ and McCormack pulled a pistol and exchanged fire with the IRA men before he was killed. [11] If the two were indeed spies, it is logical that they would have had a cover story.

On the other hand, Collins himself appears to have later acknowledged that McCormack, at any rate, had been targeted by mistake and that he was not aware of any evidence against him.[12]

However, if the operation was not as clinical as some would like to paint it and if it did not ‘wipe out British intelligence’ in Dublin as is sometimes claimed, this does not mean that it was ineffective. In fact it terrified and paralysed the British Intelligence operation, at least in the short term.

The Military noted:

‘The Murders of November 21st 1920 temporarily paralyzed the Army Special Branch. Several of its most efficient officers were murdered and the majority of other officers were brought into the Castle and the Central Hotel for safety. This centralization in the most inconvenient of places possibly greatly decreased the opportunities for obtaining information and for re-establishing anything in the nature of a secret service.’[13]

In short, it succeeded in its aim of eliminating the immediate threat to the IRA leadership in Dublin.

Croke Park

Given the climate in Ireland in late 1920, it was almost a certainty that Crown forces would enact some sort of revenge for the killing of their colleagues that morning. But why did Crown forces raid Croke Park?

Reports reached the IRA that afternoon via sympathetic DMP policemen that the British planned to raid Croke Park and search the crowd attending the Dublin Vs Tipperary football game for arms. This had been ordered by Army commander Nevil Macready, probably on the misconception that like Breen and Treacy before, the shooters on Bloody Sunday Morning had come up to Dublin from Tipperary.

There was no truth in this. All of the shootings were carried out either by the Intelligence Squad or the Dublin Brigade, but a small number of IRA men who had been ‘out’ that morning did actually attend the game. Sean Russell, who had helped to plan the morning’s operation, frantically tried to have the game called off, but with a sizable crowd (estimates of between 5 and 15,000 have been given) already converging on the venue, it was too late.

The Crown forces’ raid on Croke Park highlighted many of the flaws, divided command, undisciplined personnel and indiscriminate reprisals, that undermined their campaign in Ireland.

The British operation at Croke Park exemplified many of the flaws in their counter-insurgency campaign in Ireland. Though it was ordered by the military, the raid on Croke Park was largely to be carried out by police, that is the Royal Irish Constabulary (RIC), including their Black and Tan recruits and Auxiliary Division, with the Army in a supporting role only. There were also separate commanders for each of these three components of Crown forces.

The military, a battalion of the Wellington regiment, were commanded by Lieutenant Colonel Robert Bray, the Auxiliaries by Major EL Mills and the RIC, largely Black and Tans from the depot at the Phoenix Park, by Major George Dudley.[14]

So it was a plan, based on a flawed assumption, carried out by a largely undisciplined force of which no one was sure who was in command. Not surprisingly, no one was prepared to take responsibility for the firing that broke out when the police dismounted their lorries at the southern end of the grounds.

While the Crown forces later asserted that they had been fired on first, the reports on the day told a different story. It appears as if the police opened fire almost as soon as they arrived, at ticket sellers who were running away.

Major Mills of the Auxiliaries told his superior that it was,

‘A rotten show, the worst I’ve ever seen’. ‘The regular RIC from the Phoenix Park and the Black and Tans arrived in lorries, opened fire into the crowd without reason. They killed about a dozen and wounded many more. I eventually stopped them firing’.[15]

Mills also claimed that his Auxiliaries did not fire (in fact several later testified to the Inquiry that they did) but Mills was surely correct that ‘the indiscriminate firing absolutely spoilt any chance of getting hold of any people in possession of arms.’

The military maintained that they did not fire, except in the air.

It appears as if some of the Black and Tans wanted to execute the entire Tipperary team but were stopped by Mills, again, the paramilitary policemen were probably under the mistaken impression that they were gunmen, smuggled into the city for the morning’s shootings. [16] As it was, one player Michael Hogan, was among the 14 dead. Another 72 people were injured either by gunfire or the resulting stampede of the crowd.

From the point of view of counter-insurgency, the operation was worse than a fiasco. Not only did it arrest no suspects and recover no arms, the massacre at Croke Park wiped out any negative publicity for the Irish republican movement that the morning’s killings may have created.

In this respect it closely resembled other reprisals taking place in Ireland at the time, largely carried out by undisciplined new recruits to the police, but excused by the government on the grounds that they were ‘terrorising the terrorists’. Hamar Greenwood the Chief Secretary for Ireland, stated in the House of Commons that the police at Croke Park had ‘returned fire’, had found 30 revolvers and that the ‘responsibility [for the Croke Park shootings] rests entirely upon those assassins [of the IRA]’.[17]

The evening

By the evening, the day’s death toll in Dublin was twenty eight dead and 77 wounded. But the day’s events were not over.

Senior IRA figures, Dick McKee and Peadar Clancy, as well their friend Conor Clune were killed in Dublin Castle by their guards, Auxiliaries of F Company. Clune was merely shot but McKee and Clancy’s bodies were found to have been badly beaten and cut up by bayonets. [18]

While the Auxiliaries’ desire for revenge for the killing of two of their number that morning may be understandable, from an intelligence point of view, the killings were senseless. McKee and Clancy were high value prisoners who knew almost everything there was to know about the IRA in Dublin. Surely there was more to be gained, from the British point of view, by prolonged interrogation of them rather than killing them?

Six further people were killed in Dublin that evening.

In any case, the government again covered for its servants with a story that the men were shot while trying to escape, ‘by officers of the Auxiliary Division RIC in self defence and in execution of their duty’.[19]

Nor was that the end of the day’s death toll in the city. A Dublin candle maker and member of the Orange Order, Henry Barnet, was shot dead near his business on Mountjoy Square at 11pm that night, by persons unknown. His Orange sympathies would suggest IRA involvement, but witnesses saw men in uniform emerge from a car and shoot him, which would suggest Crown forces, possibly in a case of mistaken identity. [20]

An Auxiliary policeman shot himself in Dublin Castle that night and in nearby Navan, a journalist was shot dead by nervous military sentries. This brought the day’s death toll in and around Dublin to thirty four, of whom twenty were civilians.

The following night, while imposing a curfew, some Auxiliaries opened fire on a crowd on Capel Street, killing two more people, a 71 year old man a 14 year old boy. [21]

Political impact

Finally, though perhaps most importantly, what was the political impact of the day’s events?

A recent television documentary named ‘Hawks and Doves’ hosted by former British politician Michael Portillo, claimed that the events of Bloody Sunday hardened the resolve on the British side, making some previous moderates or ‘doves’ into ‘hawks’.

This is overblown. Secret talks between Arthur Griffith and Prime Minister Lloyd George, via an intermediary, Patrick Moylett, had already commenced. Lloyd George’s private response to the killing of British officers that morning was almost dismissive;

‘Ask Griffith for God’s sake to keep his head and not to break off the slender link that had been established. Tragic as events in Dublin were, they are of no importance. These men were soldiers and took a soldier’s risk. [22]

Griffith himself, acting president of the Irish Republic, was in fact deeply disturbed at the IRA’s actions, about which Collins had not consulted him. He was arrested and temporarily imprisoned by British troops after Bloody Sunday. Brind, the head of Army Intelligence maintained it was for his own safety, which in this case might be true, to keep him safe from assassination at the hands of ill-disciplined police squads.

Back channel talks about a truce, facilitated, as it happens by Bishop Patrick Clune, whose nephew Conor was one of those killed in Dublin Castle on Bloody Sunday, went on until December, when they broke down over British insistence that the IRA surrender its arms before negotiations could begin in earnest. They were not restarted until the following summer when they eventually led to the Truce of July 11, 1921.

In that respect Bloody Sunday changed nothing.

What it and similar events did was to ensure that the Dail government and its military wing would enter talks not as defeated rebels but as undefeated belligerents. If that changed the ultimate outcome of those talks, we may only speculate.

Listen also to our podcast on the Croke Park massacre with author Michael Foley here.

References

[1] Peter Hart, Mick, The Real Michael Collins, p158-160, Collins was interned at Frongoch from April to December 1916. He was later arrested on Dublin’s O’Connell St by DMP Detectives on April 2, 1918 held for about two weeks on remand in Sligo jail before being released on bail.

[2] Dominic Price, We Bled Together, Michael Collins the Squad and the Dublin Brigade, Kindle edition Loc2529

[3] Joseph Connell, The Shadow War, Michael Collins and the Politics of Violence, p.235

[4] Price, We Bled Together, Kindle edition, loc 3008

[5] The Last Post, (1986), p.105-109. They were Michael O’Rourke, killed on Gloucester St, 17 October, John Sherlock, killed in Skerries 27 October,

[6] Price, We Bled together, Loc 3024

[7] Peter Hart, Mick, The Real Michael Collins, p.241

[8] Charles Townsend, The Republic, The Fight for Irish Independence p.203-204

[9] Charles Dalton, Bureau of Military History, WS434

[10] Michael Foley, The Bloodied Field, Croke Park, Sunday 21 November 1920, The O’Brien Press, Dublin 2014)P.158

[11] James Cahill BMH WS 503

[12] This website has a wealth of information on the events of the day from the British point of view. McCormack’s entry is here Wilde’s is here.

[13] Padraig Yeates, A City in Turmoil, Dublin 1919-21 p.193

[14] Foley the Bloodied Field pp, 161-178

[15] Foley, p.196

[16] Ibid, p.198-199

[17] Ibid. P.219

[18] Price, We Bled Together, Kindle edition Loc3478

[19] Ibid. Loc 3478

[20] Eunan O’Halpin in Davdi Fitzpatrick, ed. Terror in Ireland p.144

[21] Foley Bloodied Field, p.199

[22] Connell, Shadow War, p.240