‘The only Irishman that was incorruptible’: Seán Russell and the IRA (Part One, 1893-1930)

By Gerard Shannon. This is the first in a two-part article.

It was a grim, low-key farewell. On August 14th 1940, roughly 100 miles west off the Galway coast, an unconventional funeral was held for Seán Russell, the now-late Chief-of-Staff of the Irish Republican Army (IRA). At the time of his death, Russell was 46 years old.

On the instructions of the commander of the German U-Boat in which Russell had spent his final, torturous days, the vessel surfaced for a brief ceremony. Russell’s remains were subsequently buried in the Atlantic with full Naval honours – wrapped in a Nazi flag, so far removed from the normal rituals of an Irish republican burial of so many of his fallen comrades.[1]

Sean Russell has gained notoriety for his involvement with Nazi Germany in 1939-1940 but he had a long prior career in Irish Republicanism.

Those present for the farewell were the German crew, along with Russell’s old comrade in the IRA, Frank Ryan.

Ryan had spent much of the intervening years fighting on the defeated Spanish republican side against the fascist forces of General Franco in Spain, ultimately ending up in a prison there. Fate had recently reunited him with Russell, with whom, rather intriguingly, he maintained good relations, despite the sometimes fierce political differences they had over the direction of the Irish Republican Movement in the previous decade.

It had appeared as if Ryan would be crucial to Russell’s cooperation with the Nazi Foreign Office for German involvement with the IRA in Ireland, but without Russell, such pans collapsed. Such was the seriousness of Russell’s presence in Berlin, that he had even had at least one meeting with Hitler’s Foreign Minister, Joachim Von Ribbentrop. Ryan, however, had been left much in the dark as to this planning, and after Russell’s death, the viability of any such plans was now uncertain. Ryan returned to Germany.

Seán Russell today leaves a complicated legacy. For adherents of a militant strain of Irish republicanism in the eighty years since his death he is an unreconstructed militarist who is still regarded as a personification of physical force Irish republicanism. To others, not given to republican sympathies, this is a moot point, given Russell’s own willingness to seek the aid of a brutal regime responsible for multiple crimes of genocide and for the invasion of small nations.

To this line of thinking, it matters not how much seeking this aid adhered to the old republican slogan, ‘England’s difficulty is Ireland’s opportunity.’

The question endures, what is more true to the totality of the life he lived: to refer to him as a willing Nazi collaborator or a true Irish republican icon? Who indeed, was the real Seán Russell?

Early Life to the Rising

Russell was born John Russell on 13th October, 1893 at 41 Lower Buckingham Street in inner city Dublin. He was the youngest among three sons and four daughters of his father, James, a clerk, and his mother Mary.[2]

The 1911 census identifies Russell at age 17 working as a draper’s assistant. By then, the Russell family were residing at 76 North Strand, in the Mountjoy area of Dublin.[3]

Swept up in the tide of nationalist fervour typical of those of his age in this period, Russell joined the Volunteers in 1914. So began a close kinship with his local ‘E’ company of the 2nd Battalion, Dublin Brigade of the Irish Volunteers. Liam Daly recalled first meeting Séan Russell in January 1916, already the section commander of ‘E’ Company.

Russell joined the Volunteers in 1914 and fought in the Easter Rising with E Company, 2 Battalion, Dublin Brigade.

Daly was struck by how ‘even at this early stage and without any military training he infused a high standard of efficiency in his small group.’[4] Already, at this early juncture in his revolutionary activities, Russell was proving to be a natural leader.

Nor was Russell to be found wanting in actual combat. At the outset of fighting during the insurrection of Easter Week 1916, Russell was appointed second-in-command to Oscar Traynor; the latter led a group of rebels took over the Metropole Hotel as instructed by James Connolly. Traynor recalled how the group began to dig holes to navigate through the block.[5]

By Friday, with the Metropole hotel engulfed in flames, Russell delivered to Traynor a message for the group to evacuate the block, and after some confusion over the course of several hours, Traynor led his men to follow the rest of the GPO garrison into Moore Street terrace.[6] Traynor later said of Russell: ‘During the terrible experience, for the citizen soldiers, of the intensive shelling and eventual burning out of our position, he was an inspiration to all.’[7]

Liam Daly noted in Frongoch that Russell tended to keep aloof from his fellow prisoners, only associating with those with whom he fought in Easter Week. Like most internees, Russell was released by Christmas 1916.[8] On his return to Ireland, Russell returned to the reformed E Company, 2nd Battalion. When his former captain resigned, the later head of the Dublin Brigade, Dick McKee, assumed temporary command. McKee later appointed as captain ‘the unanimous choice’ of ‘E’ company, ‘the quiet, unassuming, but efficient section commander, Séan Russell.’

Daly claimed from ‘that day on the morale and efficiency of ‘E’ company’ became a by-word, not only in the Dublin Brigade, but also GHQ.’[9] Such was Russell’s dedication to the company, ensuring regular fielding training, drill, and manoeuvres that it ensured his later promotion to both O/C of 2nd Battalion, Dublin Brigade and quartermaster for Dublin IRA HQ.

Daly recalled how despite this Russell still kept a ‘fatherly eye’ on his old company throughout the conflict.[10] Daly’s affection for Russell is obvious in account of the latter’s activities in the early 20th century, Daly summing Russell up as ‘the only Irishman that was incorruptible, and may his memory be such as to induce this virtue in Irishmen to come.’[11]

The War of Independence

During the conflict known as the War of Independence, that developed from January 1919, Russell rose to prominence in the republican military movement.

In March 1919, Daly proposed Russell for membership of his circle of the IRB. On returning from the meeting, Daly was struck by how much of a ‘momentous’ occasion this seemed for Russell on his admission to the secret society. Daly recalled how Russell ‘spoke in a quiet tone but with a crispness and brevity of words that was a part of him… ‘Liam,’ he said, ‘were it not for Easter Week, I would be in a monastery…’’[12]

In May 1920, Russell succeeded Frank Henderson as Commander of the 2nd Battalion, Dublin Brigade, a position he held until the following November, when he was promoted to Director of Munitions on the IRA General Headquarters Staff.[13]

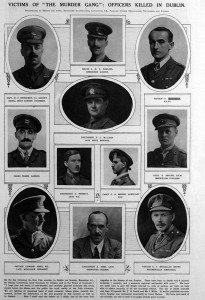

Russell was given a central role in the planning of the IRA operation on Bloody Sunday, 21st November 1920 in which dozens of British agents identified by IRA intelligence were to be assassinated in various locations around the city that morning.

As commander of Dublin 2 Battalion in 1920, Russell was tasked with planning the IRA operation to kill British intelligence officers on Bloody Sunday, November 21.

The task assigned to Russell was to select the units of IRA men to carry out the execution of the alleged British agents; twelve operations in all. Five of these operations included men from Russell’s own 2nd Battalion, joined by members of the Michael Collins’ Squad and IRA GHQ intelligence on specific operations.

The units at each location would include men who would enter the target’s house and carry out the shooting, those in holding positions, providing security outside and and members of Cumann na mBan, who were also in place nearby to clandestinely remove weapons and ammunition after the ‘jobs’ were done.[14]

Russell appointed Patrick Moran, a captain of D company, 2nd Battalion, to target three secret service men staying at the Gresham Hotel, Sackville Street. But elsewhere he insisted on appointing members of the Squad, more experienced assassins, to head the units carrying out the other operations.[15] Harry Colley recalled Russell addressing the men taking part in the operations on the previous night in Tara Hall, Glouchester Street [today Seán MacDermott Street].

Russell reminded those present that ‘that it was vitally necessary for the success of our fight that they [the spies] be removed; that no country had scruples about shooting enemy spies in war time; that if any man had moral scruples about going on this operation he was at full liberty to withdraw and no one would think any the worse of him; that he wanted every man to be satisfied in his conscience that he could properly take part in this operation.’[16]

The IRA units involved were to submit after-action reports which would be reviewed by Russell, and the O/C of the Squad, Paddy O’Daly.[17]

In the week prior to November 21, Russell also secured the family home, on 17 North Richmond Street, of Catherine Byrne, a member of Cumann na mBan, in order to function as a first aid station if any of the men on the operations were injured.[18] (Russell would also ensure the same residence function as a safe house for Frank Telling, following his dramatic escape from Kilmainham Gaol in February 1921).[19]

As it was, 14 British officers were killed in the morning’s shootings and five more wounded. That afternoon, through a police informant (a DMP sergeant), Tom Kilcoyne, O/C of ‘B’ Company, informed both Seán Russell and Harry Colley of the possibility of the Auxiliaries carrying out reprisals on the crowd at the Dublin and Tipperary Gaelic football game at Croke Park.

At the Jones road entrance to Croke Park, just prior to the match proceeding, Russell argued at length with GAA officials to prevent further members of the public gaining admittance – and evacuate those who had already assembled in the stands. The match then began, and all three men were dismissed by officials and departed the area.[20]

Needless to say, his efforts to halt the match were unsuccessful and British forces opened fire on the crowd, killing 14.[21]

Late that afternoon, Oscar Traynor, Vice Brigader of the Dublin Brigade, recalled Michael Collins instructed him and Russell to assemble the best men of the 2nd Battalion to attempt a rescue of Commandant and Vice Commandant of the IRA Dublin Brigade, Dick McKee and Peadar Clancy, who had been arrested the night before, from the Bridewell. Collins had requested Traynor meet him at 46 Parnell Square.

Collins’ intelligence was faulty however, McKee was instead taken to Dublin Castle, and Traynor, Russell, and Collins himself avoided a narrow escape from the authorities who swooped on 46 Parnell Square. McKee and Clancy, along with a civilian friend of theirs, were shot by the Auxiliaries in Dublin Castle that evening[22]

After Bloody Sunday he was made IRA Director of Munitions by Michael Collins.

It was following Bloody Sunday that Michael Collins appointed Russell as Director of Munitions to succeed the Clancy; a sign perhaps that Russell’s planning had impressed the Director of IRA Intelligence.[23]

The appointment apparently came at great protest to Collins from Oscar Traynor who had assumed command of the Dublin Brigade, wishing for Russell to be his second in command.[24] Thomas Young, on the IRA munitions staff, was to claim Russell’s appointment did not have the approval of him or others involved in munitions.

Young felt ‘Russell had no engineering ability but considered himself, by virtue of his appointment, to be in a position to instruct and direct all munitions workers.’ Young’s own disgruntlement at Russell ascending to the position led to his own dismissal from the munitions staff.[25]

However, in the opinion of Oscar Traynor, ‘Russell was a tremendously keen Volunteer, and had an extraordinary bent for organising and establishing matters of this kind.’[26]

Traynor recalled Russell’s innovation in establishing and overseeing munitions factories throughout the city. Each of these factories seemed to serve a different purpose: the casting of grenades, or the brass work and the finishing of the grenade shell, and finally, the insertion of the explosive material and the detonator. The finished grenades were passed to the Quartermaster’s department, which then issued them to Volunteers.[27]

Russell feared the possibility of all the work being lost in one enemy raid, which explained the wide spread of the various factories; the main munitions factory was at 198 Great Britain [Parnell] Street, other areas included Crown Alley, Luke Street and Peter Street.[28]

To Traynor, there were great improvements now in the type of grenade issued to Volunteers courtesy of Russell, that the ‘old complaint from which Volunteers suffered previously, that of throwing a grenade and not seeing it explode, was almost eliminated.’

This in turn allowed for ‘a greater confidence in the fighting men of the various units.’ Russell similarly improved on the production of landmines, distributing the plans to various IRA Divisions across the country.[29]

As a result of his position on IRA GHQ, Russell was one of thirteen individuals depicted in artist Leo Whelan’s painting of the IRA leadership by the time of the Truce. Whelan, at the suggestion of Richard Mulcahy’s wife, Min Ryan, wanted to take advantage of the opportunity of the men now being able to appear to public.

The painting today hangs in the National Museum of Ireland, Collins’ Barracks, near the ‘Soldiers and Chiefs’ exhibition. (In the painting, Russell is seated second from right, between Eoin O’Duffy and Seán McMahon).[30] Whelan completed the painting in late 1922, or early 1923, by which time many of those depicted together were now opposed to each other in the Irish Civil War.

Civil War

Following the signing of the Anglo-Irish treaty in December 1921, Russell was one of only four members of IRA GHQ opposed to the settlement, along with Rory O’Connor (as Director of Engineering), Seamus O’Donovan (as Director of Chemicals), and Liam Mellows (as Director of Purchases).

In January 1922, at an office in Marborough Street, Rory O’Connor gathered a group of the IRA leaders opposed to the Treaty, at which Russell was present.

As the opposition of the men gathered to the settlement became more considerable and public, O’Connor proposed regular meetings of these anti-Treaty officers and was subsequently elected chairman.[31]

Russell vehemently opposed the Treaty and was one of the IRA faction that occupied the Four Courts in April 1922.

Russell was recalled by O’Malley as central to the drafting of a statement by the Anti-Treaty officers to Richard Mulcahy, then IRA Chief-of-Staff, demanded the holding of an IRA Convention that March.[32]

O’Malley vividly noted how at this first meeting Russell ‘twisted and untwisted his hands as he spoke, the fingers pressing the knuckles of the other hand. He threw himself forward when he stood up. The lapels of his coat went further back and his body turned to one side. His even teeth showed when he talked. …his kindly, ready smile betrayed no trace of his death-dealing work.’[33] Russell, not surprisingly, again assumed the position of Director of Munitions on the new anti-Treaty IRA Executive following the Convention’s rejection of the authority of Dáil Éireann.[34] This was indicative of the respect held for his work in this role during the 1919-21 period.

Following the seizure of the Four Courts by the anti-Treaty IRA Executive in April 1922, Russell joined the anti-Treaty garrison in the building. Una Daly, secretary to Liam Mellows, recalled Russell telling her in ‘great distress’ how he had witnessed Seamus O’Donovan losing a hand after testing a bomb there.[35]

During the subsequent attack on the Four Courts, and the ensuing battle of Dublin, Russell managed to evade capture for some time, but O’Malley noted his arrest by Free State forces in early August.[36]

Some weeks later however, O’Malley was delighted to report to the IRA Chief-of-Staff Liam Lynch of Russell’s escape from ‘Longford and is now with us. He is a God-send and I expect that we shall have some return from this Branch.’[37]

Subsequently, Russell was to resume his role of attempting to run bomb-making factories in Dublin, along with Seamus O’Donovan, Director of Chemicals. O’Malley noted how both men ‘had been in charge of these departments during the Tan fight, but the machines were now with the Staters’ – nor would the IRA quartermaster Joe O’Connor distribute explosives to O’Malley in Dublin.[38]

Recalling an inspection of the Dublin munitions centres in this period, Joe O’Connor conveyed ‘the highest praise to Seán Russell for his energy in overcoming great difficulties and for the quality and number of grenades he produced. If only half his energy and enthusiasm had been shown by other officers, the Republican Army might still have won the war.’[39]

Whatever his limited resources, O’Malley nonetheless recognised Russell’s value, and appointed him his adjutant-general for the Eastern Command.[40] As a result, Russell within Dublin, like the rest of O’Malley and his staff, was frequently on the move throughout the capital. Following the arrest of Liam Mellows after the capture of the Four Courts garrison, Russell also took over his duties as Director of Purchases. As a result, Una Daly, secretary to Mellows, now worked for Russell in a similar capacity. ‘Sean, like Liam,’ Daly noted. ‘… was an idealist. He never took a penny for his work.’[41]

In the Civil War, Russell was again given responsibility for producing munitions for the anti-Treaty side but was arrested and interned in late 1922 until mid 1924.

Daly also recalled Russell’s tendency for disguise as he moved through the city, with his hair dyed and carrying a pipe, which ensured he could evade arrest for a time. Russell, according to Daly, ‘was a good-living fellow, a non-smoker and non-drinker.’[42] Moss Twomey later amusingly claimed that a police sergeant advised him to tell Russell to desist with his tendency for this particular disguise, as ‘it did not suit him.’[43]

Something of the persistent difficulties for Russell in this period can be seen in a communication to O’Malley in late October. Russell referred to a raid on a premises in Gardiner Street, ‘as a result… 3 of the munitions staff… were arrested and our machinery taken away.’ Russell assured O’Malley that although ‘the loss of this shop and staff is a great shock to the department, we can still carry on.’[44]

On November 23rd 1922, Russell was arrested at a residence in Clontarf and imprisoned in Mountjoy Gaol. His arrest was announced in an official press release from the National Army GHQ the following day.[45] He was to remain a prisoner of the Free State until well after the conflict ended in May 1923 with the ‘dump arms’ order by anti-Treaty IRA Chief-of-Staff Frank Aiken.

Liam Daly, now a National Army engineer officer at the Curragh, recalled his last, sad encounter with Russell when the later was a prisoner there following his spell in Mountjoy. Daly noted ‘when he [Russell] saw me, he looked through me. I knew I had lost caste with him. I was in a way his warder…’[46]

For hundreds of republicans the conflict was to continue in the Free State jails with hunger strikes in protest at their continued imprisonment. By the time the protest was abandoned, with three anti-Treaty IRA volunteers dead, Russell himself had endured forty-one days on hunger strike.[47]

Russell was among the last group of anti-Treaty IRA officers released from the Curragh on the 17th July, 1924.[48] In his memoir of the conflict, Ernie O’Malley recalled he and Russell being released, and boarding a train at Kildare station with other senior anti-Treaty IRA officers. Arriving in Kingsbridge, O’Malley recalled the group parting ways ‘to take up the threads of inscrutable destiny; some to begin life all over again.’[49]

Rebuilding the Movement

The end of the 1920s were to see Seán Russell central to the convulsions engulfing the IRA in a dramatically changed political climate. From 1924 onward, much debate and discussion in the wider Republican movement centred on the political direction for republicanism following the defeat of the Civil War. This most dramatically resulted in Éamon de Valera founding the Fianna Fáil party in 1926, following the departure of many anti-Treaty republicans from Sinn Féin, espousing a new form of constitutional republicanism.

The dwindling IRA, nonetheless, were to maintain an association with Fianna Fáil through much of the decade, even in to the early years of the latter assuming power in the Irish Free State from 1932 – though this was to prove a turbulent, not entirely comfortable or close relationship.

The Chief-of-Staff of the IRA from 1927 to 1936 was Maurice ‘Moss’ Twomey. Twomey, a republican veteran like Russell, was to be a tireless, indispensable organiser and well-liked leader of the IRA in this period. It was nonetheless an unenviable role for Twomey, as the IRA faced diminished military prospects, dwindling membership, not to mention repression and imprisonment by both the Northern and Free State security forces.

In 1925, Russell was part of an IRA delegation to the Soviet Union.

Seán Russell himself was put on trial in November 1925, following a raid on his residence in Dublin’s North Strand by the authorities and the discovery of important IRA documents.[50] He subsequently took part in a dramatic escape from Mountjoy Gaol, along with other imprisoned IRA leaders.[51] This escape would form part of a charge that was to result in a brief return to prison for Russell in 1927.[52]

A noteworthy, if unsuccessful, venture for Russell on behalf of the IRA, was travelling to the Soviet Union in 1925 in an attempt to secure arms from the Soviets. Travelling with Russell was fellow IRA leaders Gerald Boland and Pa Murray. The latter had an audience with Josef Stalin himself.[53]

From 1927-36, Seán Russell, holding the rank of Commandant-General, would take on the position of Quartermaster General on Twomey’s staff. In this role, Russell was expected to be responsible for the supply and distribution of arms, equipment and ammunition to IRA units.[54] Twomey, in his tenure as Chief-of-Staff, felt it was important to keep a firm hand on such a strong personality as Russell.[55]

However, as the subsequent decade was to prove, the deeply militant, uncompromising Russell was to emerge as central to the intense political debates that would engulf a divided IRA – preferring the beginning of a new military campaign then flirtation with class politics.

For years regarded as a gifted operator within the IRA leadership, Russell’s disillusionment with a new political drift would see him operating outside the IRA Army Council to increase his influence over IRA members – all with the aid of a key ally in the United States. A dramatic court-martial that resulted was to paradoxically only heighten the popularity among his supporters.

As much as the considerable military prestige he built up in the IRA in the years previously, these events through the 1930s were crucial in his convoluted journey to ascend to the position of IRA Chief-of-Staff and his fateful journey to Berlin in 1940.

Part II of this article is here.

Gerard Shannon is a historian, resident in Skerries, north county Dublin. In 2019, he graduated with an MA in History from the DCU School of History and Geography. He is currently developing a biography on the IRA Chief-of-Staff Liam Lynch to see publication by the Merrion Press imprint in late 2021. His website can be found at gerardshannon.com

References

[1]The United Irishman, October 1951, Vol. 3, No. 9. It is important to note the source for mention of the Nazi flag is in a republican newssheet, in an article sympathetic to Russell.

[2] ‘Séan Russell’ biographical entry by Brian Hanley, Dictionary of Irish Biography, accessed online 2 June 2020.

[3] 1911 census entry for the Russell family: http://www.census.nationalarchives.ie/pages/1911/Dublin/Mountjoy/North_Strand_Road/22515/, accessed online 2 June 2020.

[4] Bureau of Military History Witness Statement No. 425: Liam Daly, p.1.

[5] BMH W/S No. 340: Oscar Traynor, p.15.

[6] Ibid, pp 16-23.

[7] Wolfe Tone Weekly, Vol. 2, No. 42, 14 June 1939. [reprint of a 1927 article].

[8] BMH W/S No. 425: Liam Daly, p. 2.

[9] Ibid, p. 3.

[10] Ibid. Daly notes Russell became ‘Vice-Brigade O/C’, but he was in fact promoted to Quartermaster, and later Director of Munitions, on the Dublin Brigade HQ staff, as well as O/C of the 2nd Battalion, Dublin Brigade, see below citations. He was initially Vice-Brigader of the Dublin Brigade on the death of Peader Clancy, see Dominic Price, We Bled Together: Michael Collins, the Squad and the Dublin Brigade, (Cork, 2017), pp 39, 162.

[11] Ibid, p.6.

[12]Ibid, p. 3.

[13] BMH W/S No. 821: Frank Henderson, p.81.

[14] Price, We Bled Together, p.162,

[15] T. Ryle Dwyer, The Squad and the intelligence operations of Michael Collins, (Cork, 2005), p.170.

[16] BMH W/S No. 1687: Harry Colley, p.52.

[17] Price, We Bled Together, p.170.

[18] BMH W/S No. 648: Catherine Byrne (Rooney), pp 19-20.

[19] Ibid, p.22.

[20] BMH W/S No. 1687: Harry Colley, pp 54-55.

[21] ‘Bloody Sunday’ by Ernie O’Malley, Dublin’s Fighting Story 1916-21: Told by the Men Who Made It, (Cork, 2009 edition), p.292.

[22] BMH W/S No. 340: Oscar Traynor, pp 54-57.

[23] Ibid, p.40.

[24] Wolfe Tone Weekly, Vol. 2, No. 42, 14 June 1939. [reprint of a 1927 article].

[25] BMH W/S No. 531: Thomas Young, p.16.

[26] BMH W/S No. 340: Oscar Traynor, p.40.

[27] Ibid, pp 40-41.

[28] Price, We Bled Together, p.46.

[29] BMH W/S No.340: Oscar Traynor, p.41.

[30] ‘Leo Whelan’s IRA GHQ Staff, 1921’ by Risteárd Mulcahy: https://www.historyireland.com/20th-century-contemporary-history/leo-whelans-ira-ghq-staff-1921/ (accessed online 13 June 2020).

[31] Ernie O’Malley, The Singing Flame, (Cork, 2012 edition), pp 66-68.

[32] Anne Dolan and Cormac K.H. O’Malley, ‘No Surrender Here!’: The Civil War Papers of Ernie O’Malley 1922-1924, (Dublin, 2007), pp 13-14.

[33] O’Malley, The Singing Flame, p.70.

[34] Ibid, p.84.

[35] BMH W/S No. 610: Una Daly, p.6

[36] Ernie O’Malley to Liam Lynch, 6 August 1922, UCD Archives, Ernie O’Malley Papers, P17a/55.

[37] Ernie O’Malley to Liam Lynch, 24 August 1922, UCDA, Ernie O’Malley Papers, P17a/55.

[38] O’Malley, The Singing Flame, pp 209-10.

[39] BMH W/S No. 544: Joe O’Connor, p.19.

[40] Memo from Ernie O’Malley to Liam Lynch, 22 September 1922, UCDA, Moss Twomey Papers, P69/40(68).

[41] BMH W/S No. 610: Una Daly, p.5.

[42] Ibid, pp 5-6.

[43] Uinseann Mac Eoin, Survivors, (1987, 2nd edition), p.571.

[44] Seán Russell to Ernie O’Malley, 21 October 1922, UCDA, Ernie O’Malley Papers, P17a/65.

[45] Freeman’s Journal, 24 November 1922.

[46] BMH W/S No. 425: Liam Daly, p.5.

[47] ‘Séan Russell’ biographical entry by Brian Hanley, Dictionary of Irish Biography, accessed online 2 June 2020.

[48] Irish Independent, 18 July 1924.

[49] O’Malley, Singing Flame, pp 368-369.

[50] Irish Independent, 20 November 1925; Ibid,

[51] Uinseann Mac Eoin, Survivors, (1987, 2nd edition), pp 564-65.

[52] Irish Independent, 15 November 1927.

[53] Uinseasnn MacEoin, The IRA in the Twilight Years, (Dublin, 1997), pp 642-43.

[54] Hanley, The IRA 1926-1936, p.20.

[55] Uinseann Mac Eoin, Survivors, (Dublin, 1987 2nd edition), p.571.