Internment on the Prison Ship Argenta

Internment in Northern Ireland 1922-23. By Ann-Marie McInereny

It has been argued that Ireland experienced not one but two civil wars in 1922. The first between Republicans and the new unionist government of Northern Ireland in the first half of the year and the second in the latter part of that year and into 1923, between pro and anti-Treaty factions in the Irish Free State.

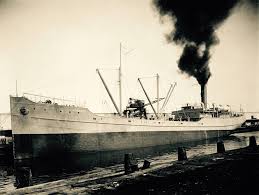

Both ended in defeat for Irish Republicans and both led to mass internment of their fighters and activists. In the North, the principle site of internment was on the prison ship Argenta.

Around 700 Republicans were interned aboard the ship Argenta in Belfast from 1923-24.

A month before the outbreak of Civil War in southern Ireland, the Stormont administration was in the process of arresting and interning men and women who were suspected of acting in a ‘manner’ prejudicial to the state. As early as March 1922, politicians warned of the growing conflict in the North. Ulster Unionist Party M.P., Robert Lynn, highlighted the growing unrest in an address to the Stormont government in which he remarked that

…it is the business of every loyal man and woman to rally around the Government…I have told my constituents often when they complained of what was happening before the 21st November [when power was transferred to the new Northern Ireland parliament] to “wait until our own parliament gets control.” We have got control, and I am sorry to say the position is not better but worse…it is time it should end…[1]

The situation to which Lynn referred was the downward spiral of law and order in Northern Ireland.

The social and political change that engulfed the island from 1919-21 had resulted in a rapid escalation of violence. The IRA, though divided by the Treaty, launched a renewed offensive on Northern Ireland in May 1922. Conflict between Republicans and the state was accompanied by severe sectarian violence, especially in Belfast.

David Fitzpatrick remarked how ‘riots, killings, burnings, and economic conflicts initiated in the mid-1920 resumed with increased ferocity after the truce…Sectarian and political violence peaked in 1922, when nearly 300 murders were officially enumerated in Northern Ireland. The murder count exceeded 30 in each month between February and June, rising to 80 in May before subsiding to a trickle after September’.[2]

Internment

In response to the IRA assassination of the Unionist M.P. William Twaddle, the Northern government decided to implement sweeping arrests and on the night of the 22nd-23rd May large scale ‘raids commenced’.

Some ‘202 people were picked up’ and within a few weeks 300 persons ‘almost all Roman Catholic males- were detained, most to be served with internment orders’.[3] Though a handful of loyalist paramilitaries were interned after October 1922, the vast majority of those imprisoned from May 1922 onwards were Republicans.

Internment was introduced in May 1922 after the assassination of MP William Twaddle by the IRA

Sean McConville stated that ‘within two and a half years, a total of 732 persons were interned. They were drawn from across Northern Ireland as follows: Belfast, 217; Antrim, twenty six; Armagh, seventy two; Down, ninety eight; Fermanagh, sixty four; Derry, seventy five; Tyrone, 180’.[4]

However, the Stormont government had only three prisons at its disposal (Derry Gaol, Belfast Jail and Armagh Prison). Due to the limited accommodation available for internees, the government later acquired a prison ship, the S.S. Argenta and Larne Workhouse as internment centres.[5]

The majority of those arrested in Belfast were sent to the S.S. Argenta and then sent to Larne Workhouse, Belfast Prison or Derry Jail. The prison in Armagh was used solely for the internment of female prisoners, similar to the North Dublin Union in the Free State, which interned female prisoners in 1923.

As a result of the escalating internment figures, the prison system became the focus of political debate in Stormont. Dawson Bates continued to highlight the inadequacies of the prison system, in particular, the burden of financing extra accommodation and provisions for the growing internee population. In parliament, he provided a rough outline of the internment situation stating

The provision for clothing, etc., is increased owing to some extent by the renewals rendered necessary by the malicious destruction of property by Sinn Féin prisoners…repairs and new buildings…also increased… I am referring to the time prior to the period we took over.[6]

Political and practical considerations were at the heart of Bates’ internment policy. He decided not to reopen internment camps on the basis that they were more convenient for internees, as it allowed prisoners considerable freedom of movement. Thus the prison ship, was seen as a greater deterrent and Bates stated that ‘many of these internees have been accustomed to enjoying the luxury of an internment camp, but I think they find that things on board a ship are not quite so pleasant, and many of them try to avoid going on a ship…’.[7]

One advantage of using a ship as a place of internment was that it allowed the government to completely isolate the internees from the mainland which ultimately separated the men from the immediate community. This greatly reduced the possibility of internees interacting with members of the public by shouting from their cell windows or putting their hands through bars. It also lessened the chances of escape attempts, as reported by Klienrichert in her study of internment.[8]

Wire fencing was erected around the Argenta deck to prevent internees jumping ship and swimming ashore. One disastrous but memorable escape attempt occurred when an internee, Chuck Brown, decided to bore a hole in the side of the ship, only to discover he had made this hole below sea level. Fellow internees had to hold him ‘against the deluge until the warders could get it repaired’.[9] The Argenta effectively limited the number of possible escapes which were specific to the prison environment.

Conditions

The ship itself was built in 1917 as a wooden steamer vessel and was first launched in May 1919.[10]

However, by 1922, the Argenta was condemned and ‘declared unseaworthy’ by US determination and its certificate of Inspection expired. Despite this, it was considered for purchase by the Stormont government and on 17 May 1922, the Northern administration bought the ship.[11]

The ship was purchased on the grounds that it would be less costly than internment camps.[12] Throughout the civil war period, the Argenta was used to imprison Republican activists in Northern Ireland and the conditions on board were overwhelmingly described as cramped and unsanitary.

‘Under-deck conditions in the cages were so congested and we were so crowded into such a small space that there was not room for either chairs, tables or lockers.

The under deck of the ship was converted into iron cages for the internment of prisoners.[13] Irish Volunteer, John Shields remembered in his Bureau statement that he was interned in his cage with 45 men.[14]

He recalled how the ‘under-deck conditions in the cages were so congested and we were so crowded into such a small space that there was not room for either chairs, tables or lockers.’[15] Internees complained of having no stools to sit upon and reports emerged that prisoners had to ‘squat’ upon their ‘hunkers’ to eat their food.[16]

The food was reportedly of ‘inferior quality’ with the milk provided being sour.[17] The toilets were at the either end of the deck and were ‘often stopped up, so that the overflow runs away down the cages…’.[18] Some of the men slept in hammocks while others slept in ‘lower tiered iron bunk beds’[19] Internees were given ‘wire mattresses with straw palliasses (canvass bags filled with straw)’ and as time passed, news spread that the blankets and mattresses were not changed since the prisoners arrival.[20]

Unlike internment camps, where prisoners could freely associate, the prison ship provided no such recreational area. The opportunity for exercise was minimal so when the weather was good, prisoners could walk around on the upper deck.[21]

Newspaper accounts of internment on the Argenta supported claims of poor living conditions on the ship. One account reported that there were between 300-400 internees on the wooden cargo boat.[22] Men were tightly packed into steel cages of 40-50 men, with an electric light that was left on all day.

Prisoners reportedly cut their food on the steel floor of their cages due to lack of tables.[23] It is unsurprising that in these living conditions, reports emerged of ‘kindred ailments’ among the internees including tuberculosis.[24]

While the majority of internees complained of the unsanitary conditions on the ship, there were some exceptions to the rule. One internee reportedly preferred the Argenta to the confines of the prison cell and asked to go back to the ship, as the regime there had been more open. He wrote to the Minister for Home Affairs pleading:

I beg to be transferred from Derry Prison to the S.S. Argenta or Larne Internment Camp. I have been removed from the Argenta three months ago, and I do not know why I have been removed, no charge having been preferred against me…Also I am very depressed having to spend 20 hours out of the 24 in confinement.[25]

Internal Strife

Those imprisoned on the Argenta in 1922 were fully aware of how useful the tactics of non cooperation and internal rioting was within the prison system.

As historian William Murphy highlighted in his book, Political Imprisonment and the Irish 1912-1921, various groups of Irish prisoners had regularly fomented internal disruption within camps and prisons once they were interned.

By 1921, Murphy noted that ‘the erosion of the prison system in the face of the revolution was undeniable’ as a ‘rebellious prison population had reduced an ordered system to chaos’.[26] Within months of their internment, the prisoners on the Argenta began their agitation from within.

By September 1922, the Governor of the Argenta, Drysdale, warned of the ‘aggressive and threatening attitude’ towards the prison staff on the ship.[27] In October, an unruly cohort of prisoners threatened a warder on the Argenta. The prisoners, Peter Trainor and John Boyle, told one of the warders to ‘clear out of the passage’ and threatened to throw a bucket of ‘slop’ over him and ‘punch’ the warder in the face.[28]

Two more prisoners, Robert Boyle and Charles Burns, encouraged the prisoners not ‘to clean their cages with the result that the occupants…felt a sense of intimidation’.[29] Consequently on 16 November 1922, the men were transferred to Derry Gaol and placed in solitary confinement.[30]

Prison transfers were frequent during this period, as a means of removing the unruly element within a prison or camp and break the morale among the prisoner population. However, it was through the method of passive resistance, the Hunger Strike, that prisoners led the ultimate protest against the prison regime.

Internees aboard the Argenta joined the hunger strike by prisoners started in Free State in late 1923.

The civil war in the Free State ceased in May 1923 but internment levels remained high throughout both the Free State and Northern Ireland.[31] In 1923, there were still some 752 people interned in Northern Ireland.[32] By October a series of hunger strikes spread throughout the country for the mass release of Republican prisoners. In the south, some 8000 prisoners took part in the hunger strike[33] while in Northern Ireland; there were some 500 prisoners on hunger strike by November.[34]

The internees on the Argenta also participated in this mass strike action. By the week ending 27 October 1923, there were around 157 men from the Argenta on strike.[35] In order to divide the internees, the prison staff recruited the prisoner’s commandant, James Mayne, and three others who were not on strike, to prepare food for the ships internees.[36]

Privileges were extended to those who did not participate in the hunger strike, such as the granting of personal visits from family members.[37] The prison administration removed water from the cells of those on strike and withdrew smoking privileges.

This created divisions between the men who were on strike and those who were not. Irish Volunteer, John Shields, recalled that eventually prisoners who participated in the hunger strike were removed from the Argenta to either Belfast Prison or Larne Workhouse. Shields, who did not participate in the protest, remained on the boat.

He recalled that some ‘100 men went on strike and were taken to Belfast’ and the men who later broke their strike were ‘returned to the boat’ while ‘some of the strikers were sent to Derry gaol after the strike had finally collapsed.’[38]

Release

In January 1924, the 101 remaining men on the Argenta were transferred to Belfast Jail on the Crumlin Road.[39] The men were separated into two groups and then transported by motor to the train station for Belfast. A silent crowd gathered at the railway platform when the men arrived at the station.

The last prisoners were released in 1924. Some were permanently exiled from Northern Ireland

As part of the release process, internees had to enter into a guarantee not to engage in anti-state activity and some prisoners were only granted release after agreeing to an exclusion order from some or all of the six county state. [40]

These exclusion orders were enforced as a means of limiting the potential threat to nascent state and ensuring that those who were released from prison were hindered from fomenting any further conflict.

Those released from the Argenta often had to start a new life elsewhere. Many ex-internees migrated south to the Free State in search of employment while others left Ireland for a life in America. [41]

Anne-Marie McInerney is a Librarian in Dublin City Library and Archive and holds a PhD in Irish history from Trinity College Dublin. Her PhD thesis explored the Internment of the Anti-Treaty IRA in the Free State 1922-24. She is working on a publication with Liverpool University Press on Military Imprisonment in Ireland during the 1920s and 1930s.

References

[1] N.I.P.D., Vol. II, Col. 24-5, 14 Mar. 1922.

[2] David Fitzpatrick, The Two Irelands 1912-1939 (Oxford, 1998), pp 118-9.

[3] Sean McConville, Irish Political Prisoners 1920-62: Pilgrimage of Desolation(London, 2014), p. 327.

[4]McConville, Irish Political Prisoners 1920-62, p. 327.

[5]Denise Kleinrichert, Irish Republican Internment and the Prison Ship Argenta1922 (Dublin, 2001) p. 74; Home Affairs Minute Sheet, 26 July 1922 (P.R.O.N.I., HA/5/2028.).

[6] N.I.P.D., Vol. II, Col. 515, 17 May 1922.

[7] N.I.P.D., Vol. II, Col. 515, 17 May 1922..

[8] Klienrichert, Irish Republican Internment and the Prison Ship Argenta (Dublin, 2001)

[9] Klienrichert, Irish Republican Internment and the Prison Ship Argenta, p. 162.

[10] Klienrichert, Irish Republican Internment and the Prison Ship Argenta, p. 66

[11] Klienrichert, Irish Republican Internment and the Prison Ship Argenta, p. 68

[12]Klienrichert, Irish Republican Internment and the Prison Ship Argenta, p. 68

[13] John Shields, BMH WS 928, p. 21

[14] John Shields, BMH WS 928, p. 21

[15] John Shields, BMH WS 928, p. 22

[16] Ulster Herald, 11 Nov. 1922

[17] Freemans Journal, 30Mar. 1923

[18] Fermanagh Herald, 16 Sept. 1922

[19] John Shields, BMH WS 928 p.22 ; Kleinrichert, p. 84

[20]Klienrichert, p. 84 ; Freemans Journal, 30 Mar. 1923

[21] John Shields, BMH WS 928, p. 22

[22] Fermanagh Herald, 21 July 1922

[23] Evening Herald, 21 July 1922

[24] Irish Independent, 13 July 1922.

[25]Joseph McClure to Minister for Home Affairs, 13 Mar. 1923 (P.R.O.N.I., HA/5/1502.).

[26] William Murphy, Political Imprisonment and the Irish, 1912-1921 (Oxford,2014), p. 215

[27] Governor Drysdale, Argenta to Secretary of Home Affairs, 26 Sept. 1922 (HA/5 2207, P.R.O.N.I.).

[28] Report on Peter Trainor and John Boyle SS. Argenta, 23 Oct. 1922 (HA/5 2207, P.R.O.N.I.).

[29] Klienrichert, p. 131

[30] Klienrichert, p. 131

[31] Michael Hopkinson, Green Against Green, (Dublin, 2004), p.268; Seán McConville, Irish Political Prisoners 1920-1962 Pilgrimage of Desolation, (New York, 2014), p. 338.

[32] Seán McConville, Irish Political Prisoners 1920-1962 Pilgrimage of Desolation, (New York, 2014), p. 338.

[33] Michael Hopkinson, Green Against Green, p.268

[34] Fermanagh Herald, 3 November 1923.

[35] Klienrichert, p. 218

[36] Klienrichert, p. 217

[37] Klienrichert, p. 217

[38] John Shields, BMH WS 928 p.24

[39] Irish Independent, 31 Jan. 1924

[40] HA/ 5 series contains a number of files on internees who received exclusion orders upon their release. See files of HA/5/1555 John Corr; HA/5/1559 John Cox; HA/5 1560 Andrew Corrigan, P.R.O.N.I.)

[41] (See files of Michael Hanratty, HA 5 1525 & A.K Dooris, HA 5 1573, P.R.O.N.I.).