The Border Counties in the Irish War of Independence, 1918-21

By John Dorney

The Irish War of Independence, the guerrilla conflict that raged from 1919-21, varied hugely in intensity across the country.

The main centres of violence were in south Munster, particularly in counties Cork, Kerry Tipperary, Clare and Limerick where martial law was declared, and Dublin and Belfast cities.

Contrary to what is sometimes written, what was to become the border area saw significant violence and upheaval in 1919-1921.

It has become a commonplace in Irish historical writing to compare the death toll of some 500 in County Cork in the ‘Tan War’ with the mere ten who died in County Cavan.

But Cork also had more than four times Cavan’s population. The region from Louth to Leitrim and from south Down to south Fermanagh which was soon to be bisected with a new border, which had a comparable population to Cork’s, saw at least 160 violent deaths from 1919-21. Thousands of troops and police were deployed there and there were at least four IRA active service units.

As well as the insurgency against Crown forces, this region was also the site of bitter conflict between two communities, nationalist and unionist which ended with the partition of Ireland in 1922. This article will try to tell its story.

Mobilisation

The Home Rule Crisis of 1912-1914 brought the threat of violence into politics in south Ulster and its borderlands.

In 1912-13 as part of their general resistance to of Home Rule, unionists in these counties mobilised into paramilitary grouping, the Ulster Volunteer Force.

Even in predominantly Catholic southern Ulster, this was, on paper a formidable grouping. In Cavan alone it had 2,406 men and over 2,600 rifles by 1914 and was equally strong in neighbouring Monaghan.[1]

Initially Irish nationalists in south Ulster mobilised in reaction to the creation of he Ulster Volunteer Force in 1913.

Nationalists responded with the Irish Volunteers, formed in Dublin November 1913. In the north midlands, response was initially slow but took off after John Redmond pledged Irish Parliamentary Party support for the movement in November 1913.

Very likely, the mobilisation of the Irish Volunteers in this area was motivated by a desire for self-defence should the Ulster unionists ever back up their threat of force with actions. The British authorities were worried about about the emergence of nationalist paramilitaries in particular but noted that by comparison with the Ulster Volunteers, they were very poorly armed, with only 100 rifles in County Monaghan for instance.[2]

The threat of civil war in 1913-14 was headed off by the advent of the Great War – in which the leadership of both paramilitary groupings agreed to encourage enlistment for the duration of the war. There was substantial recruitment from the north midland counties into the British Army during the war; over 1,000 men joined up in County Cavan alone.[3]

The insurrection at Easter 1916 in Dublin was initially condemned across the board by nationalist county, urban and rural councils in the area. It was the repression of the Rising in these rural areas, far from the scene of the fighting, that began to radicalise a new generation of activists.

County Cavan was, according to a local republican, scoured by patrols of the Enniskillen Fusiliers of the 36th Ulster Division (largely recruited from the Ulster Volunteers), who carried out 10 arrests. Similarly in Monaghan the local separatists were rounded up and arrested despite having played no part in the Rising [4].

The following year, with the threat of conscription for the Great War looming, released prisoners of the Rising were feted as heroes. Paul Galligan of Cavan, for instance, who had led the Rising in Enniscorthy, County Wexford, was introduced to a ‘Monster Meeting at Clones, as ‘a splendid young man that was not afraid to look into English guns on Easter Week.’[5]

The RIC noted ominously that ‘the young men’ were increasingly attracted to the new republican Sinn Fein and Volunteer movements. And it was a new generation of young men in the region, Eoin O’Duffy in Monaghan, Sean MacEoin and Sean Connolly in north Longford, Paul Galligan and Sean Milroy in Cavan, Frank Aiken in south Armagh, would lead the young generation of separatist activists into confrontation with the state.

Rioting and elections

The first widespread confrontation in region took place around the conscription crisis in early 1918, when the British government attempted to extend compulsory wartime service to Ireland.

In April 1918 as part of the national campaign of resistance to conscription, Eoin O’Duffy, a Gaelic Athletic Association (GAA) organiser and now Sinn Fein and Volunteers activist too, staged an impressive show of civil disobedience.

In defiance of an order under the Defence of the Realm Act forbidding public meetings during the conscription crisis, O’Duffy staged Gaelic football matches all across southern Ulster, which were also rallies against conscription and defiance of the ban on public gatherings.[6]

The first sustained violence in the region was rioting, mostly between rival nationalists, during the elections of 1918.

The north midland counties were among the first to elect Sinn Fein MPs and it was in these elections of 1917-18 that many of the new generation of republican activists were ‘blooded’ in confrontations with both state forces and rival political groupings. Sinn Fein leader Arthur Griffith was elected a by-election in Cavan in 1918 and Volunteers acted as security for his campaign.

Their enemies were not only unionists but also rival nationalists in the Ancient Order of Hibernians. The Hibernians, who acted as a strong-arm organisation for the Irish Parliamentary Party, were a Catholic only organisation, but, oddly, in attempting to halt the rise of Sinn Fein, seem to have made common cause with the Protestant only Orange Order.

One Volunteer, James Cahill, remembered that, ‘we were constantly on protective duty during the by-election. The Ancient Order of Hibernians were ferocious in their attacks on members of the Sinn Fein organisation. Occasionally they were assisted by the Orangemen… Frequently Hibernians or Orangemen would conceal themselves behind walls or hedges and attack us with stones as we cycled past.’[7]

In south Armagh in early 1918, Sinn Fein lost a by-election to the Redmondites. This campaign too was marred by rioting. In Newtownhamilton at a rally by Sinn Fein there was serious disorder between Sinn Fein supporters and the Volunteers on one side, and the Ancient Order of Hibernians on the other. The Volunteers, who were Clare men under Michael Brennan, mounted charges with hurling sticks on the Hibernians, to prevent them from disrupting the rally. The Royal Irish Constabulary (RIC) stood by as both factions fought it out. [8]

Many locals were impressed with the discipline and resolve shown by the Clare Volunteers during the election campaign and it was after this point that local units of the Volunteers began to be formed in the Armagh area.

In the 1918 General Election, Sinn Fein won virtually every seat in the region. This was followed up with victories in the local elections in the summer of 1920. On January 21 1919, the Sinn Fein MPs declared Irish independence and constituted themselves as the Dáil or Parliament of the Irish Republic.

Police Boycott and Dail Courts

At the same time, the Irish Volunteers or as they were increasingly calling themselves the Irish Republican Army or IRA, aspired to take over policing from the RIC on whom a boycott was placed.

Intimidation of the police was particularly effective in counties such as Leitrim and Cavan, where a high proportion, particularly of recently recruited policemen, resigned after IRA night time visits to their homes.[9]

In 1919 and 1920 republican activism and intimidation paralysed the police and courts system all over Ireland, this was true also in the north midlands.

Rioting with the police became common when the RIC tried to break up illegal drilling by the Volunteers. In Cavan for instance, the RIC came upon a party of 80 Volunteers, led by Paul Galligan drilling, on June 15 1919, in a field at Gortaree. On being ordered to disperse, the Volunteers pelted the constables with stones until the policemen produced their carbines and revolvers and threatened to fire.[10]

Intimidation and riots were common in the region in 1919 and early 1920 but lethal attacks were, as yet, not.

With the boycott of the police and their withdrawal to the larger towns, it was noted, petty crime increased throughout the north midlands. In March 1920 Cavan Assizes (courts) warned that crime was up because of the ‘impunity’ with which burglars can operate and the widespread use of revolvers in robberies.[11]

Some locals responded to the upsurge in crime by forming vigilante groups. Notices signed ‘Rory of the Hills’ [a traditional name used for clandestine land agitators, who may also have been the IRA] were posted in Ballyconnell, county Cavan threatening death to burglars if stolen money was not returned.[12]

The strategy of the republicans was to replace the British state in Ireland with Irish institutions and one of the key areas in which this place throughout the country was the court system. The north midlands was one of the first locations where this process took off and the first ‘Dáil Court’ was established in Cavan in early 1918.

By August 1920 the ‘Sinn Fein Courts, now with official backing from the Dail, were up and running. At Cootehill, for example, one Bernard McDonald was convicted of assault and threatening language towards his neighbour in a land dispute and fined.[13]

In September 1920, however the Dáil Courts were suppressed all across the country by British forces. The Courts’ staff were arrested and their documents seized. At Carrigallen and Arva for example, joint British Army and RIC raids smashed in the doors with hatchets and seized their documentation.[14]

The re-assertion of British state authority did little to help the law and order situation. The IRA was determined that the British justice system would not function and in County Monaghan for instance, visited the Justices of the Peace (judges) in December 1920 and ordered them to resign. Most did so.[15]

Barrack attacks and Guerrilla war

From early 1920 to mid 1921 the rioting that had characterised confrontations between republicans and state forces faded away and was replaced by a clandestine war between the IRA and a militarised RIC police and the British Army.

This was in part the result of the local Volunteers’ desire to arm themselves, which led to arms raids and eventually lethal attacks on state forces to seize their weapons.

But in the north midlands, the main driving force seems to have been the directives from IRA GHQ in Dublin, led by Michael Collins and Richard Mulcahy, from early 1920 to escalate the armed struggle by attacking police barracks.

Monaghan IRA led by Eoin O’Duffy successfully captured a police barracks in February 1920.

The aggression of particular IRA units depended very much on effective local leadership. In the zone that ran from Louth to Leitrim, by far the most aggressive IRA commanders were Frank Aiken in South Armagh, Eoin O’Duffy in Monaghan and Sean MacEoin in North Longford.

Eoin O’Duffy, along with Dan Hogan and visiting IRA GHQ officer Ernie O’Malley, conducted one of the first successful barracks attacks in Ireland in Ballytrain County Monaghan on February 14, 1920.

The Ballytrain RIC barracks was in a small village in rugged hill country and was manned by just six policemen. O’Duffy planned the attack carefully, setting up road blocks to intercept any possible RIC reinforcements. After a three hour fire fight the RIC constables surrendered when an improvised explosive, or in IRA terms, a ‘mine’, was placed beside the barrack wall and blew in the gable, collapsing the first floor.

O’Duffy had warned the police of the bomb through a loud hailer and told them to shelter at the other end of the building. When they surrendered he told them he was ‘glad there was no life lost’. ‘We didn’t come to do injury, only to take the arms’. He also lectured them that, since in the 1918 election ‘the people had voted for freedom’, they ‘acting against the will of the people’ and urged them to ‘join their brother Irishmen’ before letting them go.[16]

In the aftermath of the attack, the RIC and 200 British Army troops raided the Monaghan and Fermanagh area, and searched many houses but made, presumably in the absence of solid information, no arrests.[17] Even in larger towns such as Clones, the IRA was able to parade in the streets after darkness by which time the RIC had returned to barracks.[18]

O’Duffy made a strong impression on Ernie O’Malley who reported favourably of him to Michael Collins and IRA GHQ. He and Dan Hogan were arrested for a time and held in Belfast but were released in May 1920 after going on hunger strike.

Though the Ballytrain attack was not followed up other systematic attacks on rural barracks in the region, the RIC nevertheless withdrew from most of its smaller barracks in the spring of 1920 and as elsewhere they were systemically burned by the IRA at Easter 1920.

The Newry Brigade under Frank Aiken mounted a major assault on the RIC barracks at Newtownhalilton but failed to capture it.

On Easter weekend of that year, 114 rural RIC Barracks were burnt across the country by the IRA, including those at Baileboro, Standone, Crosskeys (partially) in Cavan, five more in County Longford, 9 in Meath, 2 in Leitrim and 3 in Fermanagh. Several more were later destroyed in Monaghan. Income tax records were also destroyed.[19]

In the south Armagh area Frank Aiken’s ‘Newry Brigade’ of around 200 men, were the next to attempt to take a police barracks and mounted an assault on the RIC post at Newtownhamilton on May 11-12 1920.

All roads leading to village were blocked by armed outposts and telephone wires were cut to prevent the police from calling for reinforcements. Aiken and a small party tried to blow a hole in the wall of the barracks from an adjoining public house while the main attacking party surrounded the barracks from front and rear.

Aiken called on the RIC garrison to surrender, but Sergant Traynor and the six constables inside refused, leading to a five hour fire fight. The IRA party tried to burn the barracks by pouring paraffin in through holes blown in the wall and set it alight, using a potato sprayer to hose the barracks with burning liquid. Firing went on for about five hours until 5 am, but the RIC held out until morning in an outbuilding. [20]

In the following month, June 1920, an RIC constable and an IRA Volunteer were killed in a shooting incident at fair in Cullyhanna when IRA men tried to disarm policemen. Two others were wounded, one on either side. In November 1920, RIC Head Constable John Kearney was assassinated at Needham Street in Newry.[21]

Aiken attempted another barrack attack, on December 12 1920, when the Newry Brigade assaulted Camlough RIC barracks. They planned that, while the attack lured British forces to the scene, they would ambush the British Army and RIC reinforcements at the spot known as ‘Egyptian Arch’, on the Newry-Camlough Road.

As at Newtownhamilton, a potato sprayer was used to douse the Camlough barracks with burning paraffin, but the spraying device was put out of action by RIC bullets. The police signaled for help by firing flares into the night sky and while the IRA did attack those reinforcements, the attempted ambush at Egyptian Arch inflicted more damage on the IRA than on Crown forces. Three IRA Volunteers were killed or mortally wounded by one of their own grenades which went off prematurely. There were no RIC or military casualties. [22]

Sean MacEoin of Longford made his name in the IRA in November 1920, shooting dead an RIC Inspector at Granard, and subsequently fighting off over 100 police and troops who were to set to carry out reprisals in the small town of Ballinalee.

Locals thought that three British soldiers were killed and five wounded in a 15 minute fire fight with MacEoin’s men at Ballinalee, but the authorities reported just two policemen wounded along with a civilian, Thomas McGorey, shot dead at an Army at road block in the area after the fight.[23]

Flying columns

It would be a mistake to think that large operations such as these characterised IRA activity in the region. Much more common than IRA ambushes or barrack attacks, was destruction and blocking of roads, seizing the mail, individual harassing attacks on police and troops and other such minor actions.

By the time of the truce, the roads in County Monaghan had deteriorated so badly due to the IRA campaign that the Council would no longer pay to have them repaired.[24]

Another very common activity was enforcement of the Belfast Boycott, which forbade doing business with Belfast firms due to the attacks on Catholics by loyalists in that city. Fines were imposed and goods seized of those businesses who defied the boycott. One Cavan Orangeman complained that he was ‘approached by strange men’ and threatened with shooting if he did any business with the northern city.[25]

That said, while most IRA members never engaged in open combat with Crown forces, small effective IRA active service units, capable of concerted military attacks, did emerge in some localities in the region.

Large scale IRA actions were rare and infrequent but a number of significant local flying columns did emerge in Armagh, Monaghan and north Longford.

Sean MacEoin’s North Longford column ranged all over the north midlands region, striking at the RIC at Swanlibar, County Cavan in December 1920 for instance, when a three man RIC patrol was ‘passing dead walls’ when ‘a volley of rifle, revolver and shotgun fire was poured into the patrol from behind a wall on the west side of the wall.’ One constable Peter Shannon was shot dead, hit in the stomach and head.[26]

MacEoin’s most successful action came in an ambush of Auxiliary policemen at Clonfin in Longford on February 1 1921, where, through use of a mine in an ambush of an RIC motorised column, four Auxiliaries were killed and the rest captured and disarmed.[27]

MacEoin himself was captured by the RIC about a month later at Mullingar. His arrest showed his central importance to the IRA in Longford and the region generally, as attacks in his command area declined sharply thereafter.

Large IRA operations remained rare in County Monaghan well after the Ballytrain barracks attack of February 1920. It was January 1921 before O’Duffy’s command again attempted a large scale attack. In that month they ambushed a police patrol and shot five RIC men, one fatally, and an unfortunate civilian in the crossfire, at Ballybay. Another constable was killed on the same day at Coolshannagh.[28]

It was another six months before the next large encounter in Monaghan; an ambush in June 1921, in which a cycling patrol of RIC men was ambushed at Broomfield. Ten of the constabulary were hit by rifle fire and one, a Black and Tan constable named Perkins of the Isle of Wight, was killed.[29]

In short, O’Duffy was an aggressive but not a reckless commander. He sanctioned few large scale attacks and only did so when he was sure of success.

By contrast to the Brigades of O’Duffy, Aiken and MacEoin, Counties Cavan and Leitrim developed no such effective IRA active service units. In Cavan, Paul Galligan, a veteran of the 1916 Rising, who had won a well-deserved reputation as a dedicated and talented republican activist, does not seem to have been suited for guerrilla warfare.

This was best illustrated by an event of mid 1920 in an arms raid at In May, an IRA party from Galligan’s West Cavan unit tried to ambush two RIC men at a fair in Crossdowney to take their weapons. One participant recalled; “strict orders were given by the battalion OC [Galligan] that no lives were to be taken in the attempt”.

When the police were challenged, they opened fire with their pistols. In a shootout, one of the Volunteers, Thomas Sheridan, was shot and mortally wounded, his brother Paul and one of the policemen were also injured. The police, who swore they would kill the other Sheridan brothers if the wounded sergeant died, set fire to the thatched roof of the Sheridan house that night.[30]

Galligan himself was arrested and shot and wounded by Black and Tans in September 1920 and interned in Belfast before being imprisoned in England.

Counter insurgency

Crown forces put the IRA guerrillas under increasing pressure from mid 1920 onwards. As elsewhere in the country, this was largely a result of drafting of paramilitary police in the form of the Black and Tans and Auxiliary Division.

Their reprisals could be very indiscriminate, amounting at times to attacks on the local population as a whole.

After an IRA ambush in Longford in November 1920, for instance, a force of RIC and Black and Tans burned 17 buildings in the village of Granard. Such was the damage caused that local Unionists also protested at RIC actions, including ‘Mr Major, a Protestant’, who claimed that £181,000 pounds worth of damage had been caused by the state forces’ reprisals. [31]

British reprisals were often indiscriminate, those by the Ulster Special Constabulary had a sectarian tinge to them.

On December 4, 1920, the Carrick on Shannon Creamery in Leitrim was burned in reprisal for the kidnapping of RIC constable Dennehey at Rooskey, while in the same month, at Swanlibar County Cavan, in retaliation for the shooting of a policeman, three lorry loads of troops burned houses, fired shots randomly at the townspeople and did £2,000 worth of damage in the village. [32]

The Auxiliary Division in particular often robbed households which they were supposedly raiding for IRA suspects. The Ryan family of Leitrim, for instance, were awarded £103 for having been robbed at gunpoint by Auxiliary policemen. Michael Flynn of Annaghbradigan was beaten by Auxiliaries, who also took £96 from his home. Thomas Moran, a vintner, and threatened at gunpoint and robbed of £25.[33]

From the summer of 1920 the regular Crown forces were supplemented by the Ulster Special Constabulary, a force raised from among the among the unionist population of the six counties that were to form Northern Ireland, and armed and paid by the British authorities.

The Ulster Specials, effectively a unionist militia, brought a new ferociousness to the conflict in the region, introducing into it a straightforward sectarian dynamic – targeting Catholics specifically and provoking the IRA to retaliate against Protestants and unionists.

In the aftermath of Frank Aiken’s attack on Camlough barracks in December 1920, the Specials burned Catholic owned houses (including the Aiken family home ), and shot dead two republican suspects at Belleek outside Camlough on December 28.[34]

Nine republicans were killed by the USC in the South Armagh/South Down area alone from December 1920 to July 1921. The IRA in response raided the homes of loyalists and Special Constables.

A series of events in County Armagh in 1921 illustrates the nature of this cycle of violence; On 10 April 1921, the IRA ambushed a USC patrol at Creggan on the Newry-Crossmaglen road. One constable was killed and another wounded. In revenge, the USC burned nationalist homes in the village of Killylea, near Armagh town, and shot and wounded two civilians there. The IRA in retaliation burned unionist homes and an Orange Hall in the area. This vicious circle of violence and retaliation would go on in the the region until mid 1922. [35]

Violence in the border counties was not solely between locals however. In the summer of 1921, the British Army (as opposed to the various police units) took a greater role in the region and in May 1921 conducted a huge sweep across the area using infantry, cavalry and aircraft, arresting hundreds of suspects.

Between the 30th of May and the 16th of June 1921, a cavalry column consisting of three regiments, the Carbiniers, the 10th Royal Hussar and the 12th Royal Lancers, supported by the Royal Irish Constabulary and Auxiliaries as well as by military aeroplanes, mounted a ‘drive’ through counties Longford Leitrim, Cavan and Monaghan.

They recorded arresting 600 men in Longford, 700 in Leitrim and about 900 in Monaghan, of whom about 120 were sent to the internment camp at Ballykinlar. [36]

The poorly armed guerrillas in the region could do very little against such large and well equipped forces but to avoid them and go to ground. Only one soldier of the three cavalry regiments was wounded in the operation, during a gun attack in Longford.

But if the local IRA could not take on the military, they were determined to deny them garrisons. In June 1921 the IRA burned or bombed out half a dozen country mansions, as well as courthouses and workhouses in the region to be prevent them from being used as Army bases.[37]

The only large military loss of life in the region came on June 24 1921, when Frank Aiken’s column sabotaged the rail line at Adavoyle in Armagh causing a train carrying troops to Belfast to crash, killing four soldiers a railway employee, two civilian passengers and dozens of cavalry horses.

The IRA disasters at Lapinduff and Selton Hill

IRA GHQ in Dublin was concerned that counties Cavan and Leitrim were among a number of areas not pulling their weight in the fight, and leaving south Munster, the ‘Martial Law area’, to bear the brunt of the guerrilla war.

One solution they tried was to parachute in officers from elsewhere into quiet areas to create effective flying columns. This had disastrous results for the IRA in Leitrim and Cavan and indirectly, Belfast.

In early 1921, Longford IRA officer Sean Connolly, was drafted into Leitrim to train and lead a guerrilla column there and to try to spark activity in the county. Connolly’s column was however, swiftly discovered and surrounded by a joint RIC and British Army force at Selton Hill near Mohill. He along five of his men were killed in the ensuing gun battle and the rest were captured. [38]

This disaster, apparently caused by locals telling the police of the IRA’s presence at the camp, did not stop IRA GHQ from trying again afterwards to import outside officers into Leitrim. Patrick Morrissey of Rathmines, Dublin, a veteran of the 1916 Rising and of ‘Bloody Sunday‘ in 1920, was sent to Leitrim in early 1921, after the Selton Hill disaster, by IRA GHQ to reorganise the Leitrim Brigade, serving under the name of James E. Thompson. [39]

Similarly in May 1921, there was a GHQ initiative to bring IRA Volunteers from Belfast to Cavan to train and lead a column there. Led by Seamus McGoran, one of the Belfast IRA’s two Active Service Units, of 13 men, was sent to Cavan where they were joined by about ten locals.

Attempts by IRA GHQ to set up flying columns in Letrim and Cavan ended in disaster, with entire two columns killed or captured.

Their camp at Lapinduff mountain, however was discovered within three days by Crown forces – apparently after some loose talk in a local pub by some of the Belfast men. In local Volunteer Sean Sheridan’s opinion, ‘the position was to my mind, a very bad one. It was on top of a hill which stood up like a pimple in the surrounding countryside’.

The column was surrounded by a British military and RIC party of 70-80 men, who converged on the hilltop camp at dawn. A three-hour fire fight ensued in which one IRA man was killed , James McCartney of Belfast, and another wounded, and all the rest were captured. The local press reported that one British Army soldier was also killed in the gun battle and another died of his wounds on July 16 1921.

The fourteen captured IRA men (who included Patrick Smith, a future Sinn Fein and Fianna Fail TD for Cavan) were sentenced to death but reprieved by the July 11 truce.[40]

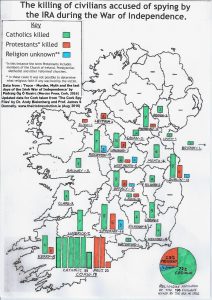

The shooting of civilian informers by the IRA

Informers could be a lethal hazard to the IRA during the War of Independence. But shooting local civilians was also fraught with difficulties, both moral and political. Some Volunteers did not want to admit that informers had been shot in their areas in the years afterwards.

Cavan man Hugh Maguire for instance said, “no spies were shot in the area and I doubt if such existed”. In fact though, at least two civilians were killed in Cavan as alleged informers.

Another Volunteer claimed that the RIC in Cavan did not need informers such was their local knowledge. Indeed, an RIC constable told the Belfast IRA men, “We know every inch of ground and I was born and reared not far from here”[41].

But the wiping out of the columns at Selton Hill and Lapinduff showed that RIC’s information was too accurate to have been simply the result of attentive police work. Seamus McKenna, one of the Belfast men captured at Lapinduff in Cavan May 1921, thought that, ‘our presence was undoubtedly betrayed to the enemy’, and he complained that, ‘no effort was made to locate and dispose of the informer’.[42]

At least 15 civilians were shot and labelled as informers by the IRA in the region.

In Leitrim, however, William Lattimer, who was accused of giving away the camp at Selton Hill, where Sean Connolly was killed and his column wiped out, was abducted and shot and his house burned.

A rough count of the whole region reveals around 15 civilian victims of the IRA, killed as alleged informers – who were almost invariably dumped on the roadsides, with the notice pinned to their bodies ‘spies and informers beware’. (Listed below) [43]

Eoin O’Duffy in Monaghan was quite ruthless in his treatment of informers. He ordered the execution, for instance, of a boy named Patrick Larmer who had been delivering IRA messages but was caught by the Crown forces and told them what he knew under threat of torture. Despite pleas for clemency by other IRA officers, O’Duffy refused to rescind his order and the boy was shot.

Killing informers may also have been a way of enforcing republican political dominance. As we have seen, in 1918 there was serious rioting between the Volunteers and the Hibernians. In 1921, O’Duffy oversaw the killing, as informers, of three Irish Parliamentary Party and Hibernian supporters who were suspected of passing information to the British.[44]

Shooting informers was viewed by the IRA leadership as a distasteful necessity to maintain the security of the organisation. On the ground, however, in many cases the motives for such killings were considerably more tangled than they first appear.

Patrick Briody, for instance, a shoemaker from the Mallaghoran area in Cavan was found, shot dead, by the RIC on May 25 1921, about three weeks after the fight at Lapinduff. The RIC had often visited his shop and the IRA suspected him of passing them information.

One Volunteer, Sean Sheridan, said that he was, “arrested, tried by court martial and shot as a spy”. But another, Hugh Maguire thought that he was raided by the IRA for serving the RIC in defiance of the boycott of the police. He refused to join the boycott and, “in the attempt to persuade him forcibly he, unfortunately was killed”.[45]

In Monaghan Kate Carroll, was a poor poitin (illicit home-brewed alcohol) distiller who fell foul of the IRA, first when they fined for her for illegal distilling and then, more fatally when they intercepted a letter she had sent to the police informing on other illicit alcohol producers.

Talking to the police about non-IRA affairs was not usually fatal. She also, however, was rumoured to be ‘pestering’ one of the local Volunteers to marry her after a short, secret affair. Whatever the motives, and despite an IRA GHQ prohibition on shooting women informers, Carroll, a 40 year old spinster and ‘by any standards a half-wit’ according to one IRA veteran, was abducted and shot five times in April 1921. Her body was dumped with the standard label, of ‘convicted spy, IRA’. [46]

The Dundalk Democrat lamented of the executions of informers that, ‘in such conditions the mere suspicion seals many a death warrant, nor is it improbable that private vengeance exacted its toll over the cover of civil turmoil.’[47]

By and large the IRA killed civilians either because they were believed to be giving information to the British, or because they physically threatened the IRA in some way. It is impossible to ignore however, that of those civilians killed as informers in the border area, a disproportionate number, five out of 15, were Protestants.

The sectarian dimension.

The IRA explicitly denied that it was carrying out a sectarian campaign. One of Sinn Fein’s TDs for Monaghan, Ernest Blythe, was a County Down Protestant.

But the fact remained that from the summer of 1920 a new border had been drawn through the zone, predominantly Catholic and nationalist to the south and predominantly Protestant and unionist to the north.

This made some form of sectarian clashes inevitable – especially since Protestant unionists were also armed and organised by the Government, into the Ulster Special Constabulary from the summer of 1920.

The IRA raided armed unionists in the sumer of 1920 to take their weapons but many were later rearmed by the British government in the Ulster Special Constabulary.

Confrontation between the rival communities – as opposed to that between the IRA and state forces – began in late August, 1920 when there was a concerted series of IRA raids on unionist households in order to seize shotguns and other weapons they were holding across counties Cavan, Monaghan, Leitrim and Meath. The IRA were especially looking for the arms that the Ulster Volunteer Force had stockpiled in the area since 1913.

In Monaghan alone there were 30 raids on houses that night. One County Monaghan Volunteer recalled, ‘In this raid we captured 20 to 30 shotguns, about 3 Ulster Volunteer rifles and a parabellum pistol. We also got a number of other revolvers’.[48]

The raids led to a number of gun battles, where the occupants resisted their firearms being taken.[49] JP Griffith, a judge, was shot and wounded at Belturbet, Cavan when he resisted the IRA raiders. In Monaghan, at least four IRA members were shot during the arms raids. One Volunteer Patrick McKenna was shot and mortally wounded, shot by a Special Constable named Fleming in IRA raid for arms at Drumgarva, Monaghan. [50]

According to one of his comrades, James O’Sullian, three local unionists, including Fleming and his son and another man named Duffy were later shot dead by the IRA (and labelled as informers) in reprisal for the shooting of IRA men on the night of the arms raids.[51]

Thereafter the British authorities collected most unionist arms to prevent the IRA getting them, though they re-armed the loyalist militias in the newly formed Ulster Special Constabulary (USC) with standard British military small arms.

Rosslea and reprisals

In 1921, a series of ugly reprisals between the IRA and the Specials played out at the village of Rosslea, County Fermanagh, and nearby Clones, County Monaghan.

In January 1921, 15 Special Constables, some from as far away as Belfast, raided Clones, breaking into and looting 15 houses. Such was their indiscipline that one was shot dead by the RIC during their looting spree and another arrested.[52]

Perhaps in response, in February 1921, the local IRA, on Eoin O’Duffy’s orders, shot and wounded a local Protestant Special Constable, George Lester, in Rosslea for his aggressive treatment of local Catholics. In retaliation for that, the local USC burned six Catholic owned houses in Rosslea and looted their shops. [53]

And to culminate the vicious circle, on March 21, the IRA, under O’Duffy’s subordinate Dan Hogan, took their own revenge in turn, when they swept into Rosslea and dragged three men, Samuel Nixon and William Gardner, both Special Constables, and James Douglas, an innocent Protestant, from their beds and shot them dead. The local press reported the week after that the Special Constabulary was ‘pouring into the district’ and the ‘Inhabitants of Rosslea have fled’.[54]

The Special Constabulary sacked Catholic owned property in Rosslea in retaliation for a shooting and the IRA in reprisal killed three Protestants, two of them Special Contables.

As the conflict reached its close, some killing in the area became more or less openly sectarian. Just before the Truce of July 11, 1921, the USC arrested and then shot dead four IRA men in the Altnaveigh area of south Down. The IRA shot dead a Protestant railway worker (mistaken, allegedly, for a Special Constable) in response.[55]

Perhaps the ugliest incident of all took place on June 12th, 1921 when a 78 year old Protestant clergyman, John Finlay, was killed in an IRA raid on his home at Brackley, near Bawnboy, Cavan.

The killing was mentioned in the British House of Commons, where Hamar Greenwood, the Chief Secretary for Ireland, called it, “a diabolical outrage”.[56] Finlay was, according to varying accounts, either shot or bludgeoned to death and his house was burned.[57] It is not clear what the motive for the killing of Finlay was, but it widely interpreted a the time an act of sectarian animosity.

There was also, at a level below the IRA campaign, a certain amount of grassroots sectarianism. In retaliation for the ‘pogroms’ against Catholics in Belfast there were what might be termed as ‘mob attacks’ on Protestants and their property in the region. In Dundalk in September 1920 , there were a wave of arson attacks on of Protestant owned businesses. Three Protestants died in the fires, which were believed to be retaliation for attacks on Catholics in Belfast, in which among other victims, a Catholic priest from Cavan had been shot dead.[58]

Republicans condemned such attacks but there was a blind spot in their thinking in relation to Irish Protestants and their role in a new Irish nation.

Sean MacEoin, after his release during the truce of 1921, told his listeners of unionists; ‘as Irishmen we are ready to receive them and give them equal treatment with ourselves and to defend their rights and interests, provided that they become good citizens of Ireland. [But] If they were to become aliens in their own land then we would treat them as aliens, and if they are unfriendly aliens well they will get unfriendly treatment.’ He added, ‘As an Irishman I love my Church’, the unspoken assumption being that a true Irishman was also a Catholic.[59].

Nor was there any reconciliation on the other side at the time of the truce. Unionist MP William Coote addressing Orangemen at Clogher, on the Tyrone/Monaghan border, on July 12, 1921 told his listeners;

‘The conference between the forces of order and the rebels might end in peace and we would rejoice… ‘but could the murderers of Dean Finlay and other murders of equal loathing and cruelty make peace?’ No, the government will find they are not dealing with men who will make a peace honourable to Great Britain’. ‘The Roman Catholic Church is behind the gunmen’. All over the world it was ‘trying to break up the free principles of government enjoyed by nations holding the truth of God. It is the anti-Christ in action’. [60]

July 1921, peace: for now.

The War of Independence was brought to a fitful end on July 11, 1921 with truce agreed between the British government and the forces of the insurrectionary Irish Republic.

This was a pause in fighting, not a peace settlement. In the short term, it meant that the IRA could come out of hiding and Crown forces would cease offensive operations. In the north, it also meant that the Ulster Special Constabulary was temporarily stood down.

The north midlands region was not among the most violent localities in Ireland, but nor was it spared considerable violence and upheaval.

Along with the fatal casualties, hundreds of young men from the area had been arrested and interned. They were released to jubilant torchlit parades after the signing of the Anglo-Irish Treaty in December 1921.

The Truce of July 1921 was only the end of the opening phase of the conflict in the border region.

However the area was also uniquely vulnerable to a resumption of hostilities in early 1922, as the Treaty confirmed the existence of Northern Ireland, an entity that most nationalists along the new border deemed illegitimate.

This would lead to a new phase of conflict in the region in 1922; the subject of part two of this article.

References

[1] Reilly Eilleen, Cavan in the era of the Great War, in Cavan, Essays on the History of an Irish County, Irish Academic Press, 2004, p177

[2] Fearghal McGarry, Eoin O’Duffy, a Self made Hero, p.20

[3] Reilly, Cavan in the era of the Great War p.184-189

[4] Reilly Cavan in the era of the Great War, p.190, Seamus MacDiarmada, Witness Statement BMH, McGarry, Eoin O’Duffy, p 24

[5] Speech Notes Recorded by the Police, CO 904/23/3, The National Archives, Kew, Richmond, Surrey, TW9 4DU, England

[6] Fearghal McGarry, Eoin O’Duffy, A Self Made Hero, p.35-37

[7] James Cahill, Witness Statement BMH

[8] Kevin O’Shiel BMH WS 1770

[9] Hughes, Defying the IRA, p29

[10] Summary of the Evidence for the Trial of Peter Paul Galligan of Ballinagh

[11] Anglo Celt march 13 1920

[12] Anglo Celt May 29 1920

[13] Anglo Celt August 14, 1920

[14] Anglo Celt September 25 1920

[15] Brian Hughes, Defying the IRA? Intimidation, coercion and communities during the Irish revolution, Liverpool University Press, 2016, p.41

[16] McGarry, O’Duffy, p.47-48

[17] Anglo Celt February 28, 1920

[18] McGarry, O’Duffy p.49

[19] Anglo Celt

[20] Matthew Lewis: Frank Aiken’s War, The Irish Revolution, 1916-1923, UCD Press 2014, p.67-72. Pearse Lawlor, The Outrages, p.22-24

[21] Lewis Frank Aiken’s War, p.68

[22] Lewis, Frank Aiken’s War p.71-72

[23] Anglo Celt November 13 1920

[24] Hughes, Defying the IRA, p58

[25] Hughes, p.88

[26] Anglo Celt January 1 1921

[27] For an account of the Clonfin ambush, see here.

[28] Anglo Celt January 8, 1921, the dead RIC men were Malone and Blair, the civilian was named Sommerville.

[29] Anglo Celt June 6, 1921

[30] Sean Sheridan Witness Statement BMH

[31] Anglo Celt November 16 1920

[32] Anglo Celt January 1, 1921

[33] The Anglo Celt, Report of compensation hearings at Carrickonshannon, January 21, 1922

[34] Lewis, Frank Aiken’s War p.71-72

[35] Lewis, Frank Aiken’s War, 78-79

[36] William Sheehan, Hearts and Mines, The British 5th division in Ireland, 1920-22, p228-234.

[37] For details of the burning campaign see https://www.theirishstory.com/2015/11/06/the-burning-of-the-big-houses-revisited-1920-23/#.XECt5GngrIU

[38] Anglo Celt March 18 1921

[39] Patrick Morrissey Military Pension 1934 MSP34REF616

[40] Anglo Celt May 14, 1921, Sean Sheridan, Seamus McKenna and Seamus MacDiarmada, Witness Statements, BMH

[41] Seamus McKenna Witness Statement BMH

[42] Seamus McKenna Witness Statement BMH

[43] Informers shot in region: All as reported in Anglo Celt:

January 1921, Alleged Informers William Charters, and William Elliot shot dead, ‘riddled with bullets’ and found dumped in lake, Garvagh, Longford.

March 9 1921, 2 men shot dead by IRA as informers Aghabog, Monaghan. Patrick Larmer, Francis McPhillips Notes pinned on bodies , ‘convicted and executed spies’.

April 1 1921. Alleged informer, Hugh Duffy, ex-soldier shot dead, Rockberry, Monaghan. 55 Protestant member of USC and UVF

April 2 1921, Father and son, Fleming, aged 24 and 61 respectively, shot dead Drumgara, County Monaghan. Unionists. House burned.

April 9, 1921 William Lattimer, farmer, Mohill, Leitrim, shot dead, alleged informer, house burned. Protestant and unionist, suspected of giving information leading to deaths of 6 IRA at Selton Hill.

April 23, Alleged informer John McCabe killed. Found tied up and shot, Carrickmacross. Note ‘convicted spy, IRA’. Ex soldier of Crossmaglen, Armagh.

Kate Carroll, alleged informer killed. Bound and shot near Aughameena, Monaghan. ‘Convicted spy IRA’.

April 30, Farmer and alleged informer shot dead, Ballinamore, County Leitrim. Protestant John Harrison, taken from home, killed. ‘Informers and traitors beware’.

May 22, Patrick Briody, shoemaker, 60 of Glan, Cavan, shot dead as alleged informer. Seized by 3 armed men. 17 gunshot wounds. ‘Spies and informers beware, IRA’

June 28, civilian Hugh Newman shot dead by IRA Lisdeegan ,Cavan, ‘convicted spy’.

[44] McGarry, Eoin O’Duffy, p.64-66

[45] Hugh Maguire, Witness Statement, BMH

[46] For a run down on the various alleged motives of the killing see, McGarry, O’Duffy, p65-66, and Anne Dolan, Ending War in Sportsmanlike Manner, in Thomas Hackey, ed, Turning Points in Twentieth Century Irish History, p21-22.

[47] McGarry, O’Duffy, p.72

[48] Euguene Sherry BMH WS 576

[49] Anglo Celt September 1 1920

[50] Patrick McKenna Pension file 1D235

[51] James Sullivan BMH WS 518, P.J. Hoey BMH WS 530

[52] Anglo Celt, January 29, 1921. The dead Constable was McCullough of the Shankill Road in Belfast.

[53] Anglo Celt February 26 1921. McGarry, O’Duffy, p59-61

[54] Anglo Celt April 1 1921, McGarry, O’Duffy, p60

[55] Lewis, Frank Aiken’s War, P80-81

[56] HC Deb 16 June 1921 vol 143 cc571-4 http://hansard.millbanksystems.com/commons/1921/jun/16/murders

[57] According to a local historian, “One member of .the Volunteer party which raided Brackley House told me that Dean Finlay’s death was an accident and not murder. He himself was present when the shot that killed the Dean was accidently discharged from a gun”. This would only make sense if the death was from a bullet and not blunt force and does not explain why the house was then burnt. T. C. Maguire, N.T, Breifne Journal of Cumann Seanchais Bhreifne (Breifne Historical Society)

Volume IV No 14 (1971)

[58] Anglo Celt September 11, 1921, they were E Wilson of Antrim, G Rice of Ardee and Alderdyce (17) of Drogheda.

[59] Anglo Celt November 1921

[60] Anglo Celt July 16 1921