The 2016 Rising centenary: What did it all mean?

By John Dorney

The year 2016 marked the centenary of the 1916 Easter Rising. At the start of the year I wrote an article outlining what I though the commemorations would signify – a complex and conflicted celebration of Ireland’s nationalist identity.

Now, looking back, what of significance happened in the 2016 commemorations? And what does it mean for the Ireland of 2017 and beyond?

A changing context

Twenty Sixteen was a year marked by a resurgence of nationalism across the West, mostly in response to the perceived negative effects of globalisation and immigration in the developed world. Ireland’s near neighbour the United Kingdom voted to leave the European Union and to ‘take back control’ of its national territory.

Politicians advancing similar formulas are on the rise in the Netherlands, France and even the European centre, Germany. The election of Donald Trump as American president is broadly part of the same phenomenon.

Ireland has yet to develop any movement of this type. By and large, Ireland has benefited hugely from being an EU member and as a low tax outpost of globalisation. Economic nationalism was tried in Ireland from the 1930s until the late 1950s and is now seen to have been a resounding failure. The Republic of Ireland joined the developed world precisely by inviting multinational companies to locate there, in the context of the European free trade area and taxing them as little as possible.

In a sense, the Irish political elite no longer really reveres the actions of the ‘men of 1916’. Their heroes are elsewhere.

At the same time as economic nationalism was rejected, the Irish state quietly jettisoned much of its programme of political and cultural nationalism. During the Northern Ireland conflict of 1969-1998, celebration of revolutionary violence of 1916 to 1923 was largely left to fringe Republican groups. Politicians in the Republic now shiver with horror at the memory of recent Republican paramilitary violence in Northern Ireland, aimed ostensibly at the great nationalist goal of a united Ireland, which threatened to destabilise the southern as well as the Northern Irish state.

Increasingly also, traditional pillars of Irish nationalist identity, Catholicism and the Irish language have been quietly side-lined as of no more practical use.

So in a sense, the Irish political elite no longer really reveres the actions of the ‘men of 1916’. Their heroes are elsewhere. On a visit to a prominent national institution recently, this writer noticed a tiny portrait of Eamon de Valera (who, as well as serving at Taoiseach for much of the 20th century was the only rebel commandant to survive 1916), but a huge and prominently placed portrait of the economist T.K. Whitaker, who along with Taoiseach Sean Lemass, pioneered Ireland’s turn towards free trade in the 1950s and 60s.

In 2011, both the Government and the state media made enormous play out of the visit of British Queen Elizabeth II to Ireland, the first monarch since independence to visit the southern Irish state. The visit showed the ‘maturity’ of Irish society and the ‘reconciliation’ of old enmities.

How then, to commemorate an armed uprising of 100 years ago in a way that neither encouraged anti-British sentiment nor the revival of Republican militarism, nor popularised isolationist nationalism that most of the leaders of the independence movement espoused?

The Rising remained too powerful a symbol of national identity for the state to ignore it or leave to fringe groups, but too potentially problematic to endorse fully and unequivocally.

An equivocal commemoration

So 1916 had to be commemorated in a way that was respectful but not triumphal, that hit the right emotional notes of celebration of the 1916 leaders and their martyrdom at the hands of British firing squads, but did not explicitly endorse any of their political goals.

As a result, the official commemorations sometimes walked a fine and awkward line. Suggestions by some to bring members of the British Royal family to the commemorations came to nothing and northern unionist leaders refused invitations to attend. Nevertheless there were many attempts to promote a more ‘reconciliation friendly’ commemoration of the Rising.

Dublin City Council for instance draped the Bank of Ireland building in Dublin, once the site of the Irish Parliament, in a massive banner commemorating great Irish leaders. It was soon pointed out, however, that those leaders included none of the Rising’s heads and in fact featured four men, Henry Grattan, Charles Stuart Parnell Daniel O’Connell and John Redmond, who explicitly eschewed political violence in pursuit of Irish independence.

Redmond, indeed was an arch rival of those who declared an Irish Republic in 1916, was reviled in separatist circles for encouraging his supporters to join the British Army in 1914 and himself condemned the Rising vociferously. The Department of the Taoiseach, whose idea it apparently was, seems to have felt more comfortable with John Redmond that with the insurrectionists Patrick Pearse, Tom Clarke or James Connolly.

The tone of the 2016 commemorations were carefully conciliatory and non-confrontational.

On Easter Sunday itself, there was much that those who commemorated the Rising’s 50 year anniversary in 1966 would have recognised; the military parade down Dublin’s O’Connell Street, laying of wreaths at the GPO, the service at Kilmainham Gaol’s stonebreakers yard, where the 1916 leaders were executed. Still, the message was quite carefully controlled. The band at the General Post Office played non-confrontational songs such as ‘Danny Boy’ and the rugby anthem ‘Ireland’s Call’ as well as the old rebel tunes. The piper playing a ‘lament’ in fact played ‘Down by the Sally Gardens’.

The wreaths at the Post office were laid by children rather than soldiers or politicians and instead of a volley of gunshots as there had been in 1966 there was a drum roll. The Taoiseach Enda Kenny’s said they were there to honour the memory of the Rising’s leaders but also to commemorate ‘all those who died in 1916’.

At Glasnevin cemetery where many of the 1916 dead were buried, the Irish Army soldiers were accompanied by uniformed British Army officers in laying wreaths at gravesides. The Cemetery itself erected as a memorial, a wall listing all 500 or so fatal casualties in the Rising, British Army insurgent and civilian, mixed together and without further comment.

Back in 1966, Sinn Fein and the Republican movement wanted nothing to do with the ‘Free State’ commemorations of the Rising. But in 2016, in an era when Sinn Fein aspires to enter the government both north and south of the border, it was different. Sinn Fein figures officially attended the state events, in the person of former Provisional IRA commander Martin McGuinness, among others.

What gave Sinn Fein a slight ‘get out’ was that there were two Rising commemorations, one set around Easter Sunday, which fell on March 27 in 2016, and another set on the actual anniversary of the insurrection, from April 25-29. Sinn Fein mostly staged its own, slightly more militaristic, commemorative events on the latter anniversary to avoid a clash with the state commemorations.

Popular response

What of the public response? By and large the Irish public responded warmly to the Rising commemorations, showing that its status a national myth is alive and well. Hundreds of thousands attended events in Dublin and large numbers elsewhere also.

Much of this was probably a desire to participate in a national holiday, some others’ interest was simply curiosity about how life was lived 100 years ago, a prominent feature of many local events.

But behind it all was still pride and admiration for what is still seen as the idealism and bravery of the 1916 insurgents. While there were critical voices, criticising the rebels for endangering the lives of civilians, turning Dublin city into a warzone and hardening divisions within Ireland, the popular tone of the commemorations was celebratory though largely apolitical. It was pride in the past rather than a programme for the future that was the order of the day.

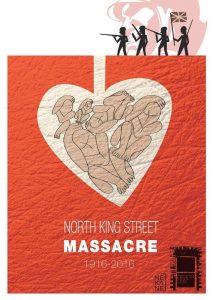

The commemorations were marked by the mushrooming of local groups formed to investigate and promote the local histories of the period. Groups of activists and relatives of 1916 veterans launched the ‘Save Moore Street’ campaign to preserve the site of the rebels’ surrender and prevent much of it from being turned into a shopping centre. On occasion, local groups were capable of uncovering a much darker face of the Rising that the official events, with their focus on ‘reconciliation’ would not touch.

On occasion, local groups were capable of uncovering a much darker face of the Rising that the official events, with their focus on ‘reconciliation’ would not touch.

The Smithfield and Stoneybatter People’s History Society for instance was to the forefront in unveiling a plaque to commemorate the North King Street massacre, in which the British Army killed 14 civilian men and boys in north inner city Dublin during the Rising. There was no state involvement either in the commemoration of this incident or in the physical memorial. It would, one assumes have given out the wrong messages.

Based on this and other incidents, one trope to come out of the 2016 commemorations is that of a ‘hidden history’ which had been covered up or erased from the history books. Sometimes this can go too far. Visitors to the recently opened Easter Rising museum at Dublin’s General Post Office, for instance are told that while women’s role in 1916 was deleted from history, women actually formed an elite of snipers within the Volunteers and Irish Citizen Army.

In fact, only two women, Margaret Skinnider and Constance Markievizc, can definitely be said to have used arms during the Rising. Nearly 3,000 men were arrested after the Rising but only 77 women. While women such as Kathleen Lynn, the Gifford sisters and others should certainly be rescued from historical obscurity, exaggeration does no one any good.

Similarly, while some would like to link the poverty in Dublin and in Ireland in general to the Rising of 1916, the connection is indirect at most. Yes some socialists of the Citizen Army came from the slums and were radicalised during the great strike and Lockout of 1913, but so too were thousands of ‘separation women’ with husbands in the British Army, many of whom tried lynch the rebels after the Rising, such was their sense of outrage and betrayal at the insurrection.

While some might still wish to enlist the 1916 in other causes, the fact remains it was primarily about securing Irish independence and no other cause.

The future of the Rising commemoration?

To sum up then, the Republic of Ireland in the twenty first century is a highly globalised country and enthusiastic member of the European Union that celebrates its identity as a fiercely independent nation state. It is a country built upon the identity of fighting Britain for independence that wants as close and friendly a relationship with Britain as possible. The 2016 Easter Rising commemorations merely showcased some of these contradictions.

In a new and possibly harsher world climate, future commemorations of the Rising may strike a different note.

As yet there has been no contradiction between a popular nationalist political identity and society that is increasingly multinational and globalised. The many thousands of immigrants who have been attracted by Ireland’s successful courting of multi-national companies over the past twenty years have so far proved fairly assimilable and have provoked no organised hostile reaction. Though there was some disquiet at the European Central Banks treatment of Ireland since the 2008 financial crisis, ‘Europe’ is not seen as a threat to national identity as it is elsewhere.

And yet, 2017, with its prospects of Britain leaving the EU, potentially raising again a ‘hard’ border across Ireland, of the EU itself seeing the rise of isolationist nationalist movements and of Donald Trump punishing multi-national companies for locating in low tax bases such as Ireland many threaten all this. Future interpretation of 1916 may be very different from those in 2016.