The Rabble and the Republic

John Dorney looks at how the Irish separatist movement interacted with the population of the Dublin slums during the years of the Great War and the beginning of the Irish nationalist revolution, 1914-1918.

On Easter Monday 1916, when the Rising, which first proclaimed an Irish Republic broke out, the Volunteers and Citizen Army fighters encountered extreme hostility not only from pro-British elements but from a section of Dublin Citizens they identified as ‘separation women’ or, ‘the rabble’.

Volunteer Thomas MacCarthy, who helped take over Roe’s Distillerry remembered;

‘During the time we were trying to knock down the gate we were practically attacked by the rabble in Bow Lane, and I will never forget it as long as I live. “Leave down your [fucking] —- rifles,” they shouted, “and we’ll beat the [shit] out of you.” They were most menacing to our lads’.[1]

Not far away, at the Four Courts, another Volunteer officer Sean Kennedy found that,

‘While I, with others, was engaged in strengthening the barricade, a number of women presumably soldiers’ wives or what was known as ‘separation women’ approached the barricade and attempted to pull it down. We repulsed their attempts. During the course of the melee one of the women, using her finger-nails, scratched me badly about the face. We eventually drove them away.’[2]

Other slum dwellers took the opportunity provided by the sudden disappearance of the unarmed Dublin Metropolitan Police from the streets to loot the city’s shops. Where Volunteers attempted to stop them, this too provoked ugly confrontations. Geraldine Dillon a Cumann mBan activist (and sister of Volunteer leader Joseph Plunkett) who was at the insurgent headquarters at the General Post Office or GPO recalled,

‘The bomb that exploded in the tram smashed Noblett’s window, and the crowd started to take out the sweets. They then started to break the other windows and general looting started. George came out of the GPO and asked for civilians to volunteer help to stop the looting. Some did volunteer and George handed them white sticks.

It was no use. The separation allowance women began to gather in the street. They crowded round the Post Office, and abused the Volunteers inside, throwing the glass from the broken windows at them. They knelt down in the street to curse them. I remember one woman kneeling with her scapular in her hand, screaming curses at them. George came out again, and waved a big knife at them, which produced some effect.’[3]

The insurgents recollections of the Easter Rising speak disparagingly of the hostility shown them by the Separation Women, or as they often called em, the rabble.

The slum women again figure prominently in the insurgents’ recollections of the surrender. One Bernard McAllister remember that as he and about 300 other rebel prisoners were being marched to Dublin’s North Wall to be shipped to captivity in Britain,

‘While going through the city to the Docks we got a very bad reception from the civil population. They booed us, called us ugly names and were generally hostile. This crowd represented the rabble of the city and not the ordinary citizen.’[4]

The above testimony is only a small sample of the statements in the Bureau of Military History collection that speak of the intense hostility that existed between militant separatists and the poorest classes – by no means only in Dublin – who were reliant on British Government benefits during the years of the First World War. Where did this hostility come from? What does it tell us about the social composition both of militant Irish nationalists and their opponents in these years?

This article is an attempt, if not to answer these questions definitively then at least to pose them with more clarity.

Who were the separation women?

Who were the ‘rabble’ of whom Bernard McAllister, a Volunteer officer from rural North County Dublin, spoke? They came, it seems certain, from the Dublin slums, where roughly 125,000 of the city’s 320,000 population lived. (Another roughly 120,000 people, mostly the middle classes, lived in suburbs beyond the city boundaries).

This was the poorest, unskilled section of the Dublin working population, whose men were generally employed in casual labour, particularly on the docks, meaning that at the best of times their wages were low and many were often unemployed. Between 1914 and 1918, 1,000 tenements were closed as unsafe, leaving around 4,000 families homeless. Some 50,000 people were thought to be in need of re-housing by 1918.

Poverty, bad diet and poor housing meant that Dublin had an unenviable mortality rate; 23.1 % in 1914 compared to 18% in Belfast and 14% in London. [5]

Inner city Dublin had long contributed many recruits to the British Army and during the Great War, the city produced around 30,000 new recruits. Some 5,000 of these men died in the War.

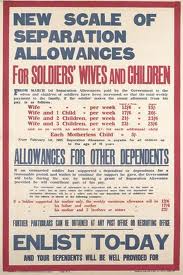

The Separation women were those, generally from the poorest part of the working class, who depended on the government allowance paid to dependents of soldiers serving in the British Army.

By no means all of those who joined up were driven to the colours by poverty. Several prominent Redmondite nationalists, including for instance Thomas Kettle, an MP for North County Dublin served (and in his case died) in the conflict in response to John Redmond’s call to join the British forces in 1914. Dublin’s roughly 90,000 strong Protestant and largely unionist community also contributed a significant proportion of recruits, who believed that fighting for the Empire was a patriotic duty.

However, the evidence suggests that economic motives did drive a considerable number into the ranks. A survey of 169 recruits from Dublin Corporation workers shows just 9, ‘salaried professional’ workers joining up compared to 113 unskilled labourers. [6]

What were the benefits of joining the Army in wartime when the chances of being killed or injured were high? For unskilled workers, joining the armed forces signified a pay rise and a chance to learn a trade. Moreover, there were also concrete benefits for the families that they left at home.

An average labourer’s pay was 16-18s for a 48 hour week – assuming he had steady work. A serving soldier got 7s a week plus free food and board. His wife received 12s 6d per week in Separation Allowance – which, including the pay the troops sent home and adding in the money saved by not having to feed her absent husband, meant a modest but significant rise in the standard of living of the slum women who were christened the ‘Separation Women’.[7]

It is clear from the statements of Volunteers and other separatist activists that there was intense hostility between them and the Separation Women, not only during the Rising in Dublin but also before and after it and all around the country. In Limerick where the Volunteers staged an armed parade in 1915, Ernest Blythe remembered; ‘the rabble of the city, particularly the “separation women” got into the mood to make trouble’.

At the train station, where the Volunteers from Dublin returned after the parade, stones were thrown, punches exchanged and some Volunteers had their rifles taken. ‘One Volunteer officer who lost his head ordered his men to load their rifles. Fortunately his instructions were countermanded, otherwise in the heat of the turmoil, irreparable damage might have been done.’[8]

In Cork city, in June 1917, there was rioting between republicans demonstrating for the release of prisoners and families with relatives serving in the British Army.[9] When the last Cork Volunteers prisoners of the abortive Rising there were released, one of them recalled, ‘The arrival of the train with the prisoners was greeted with cheers. A procession was formed, at the station and, headed by the prisoners, marched into town. On the way, the “Separation Women” did not forget to express their views and needless to say their remarks were not complimentary’.[10]

How can we account for this hostility? Speculating on the motives of people who left little or no written records of their own is an uncertain proposition, especially as most of our accounts of their actions come from their enemies. The Volunteers invariably claimed that the Separation women were merely concerned with losing their state funded income, which, the separatists claimed, the slum women merely drank away anyway.

Many relatives of serving soldiers felt betrayed by the Easter Rising

However, it seems clear that there was also a feeling among the families of serving soldiers that the ‘Sinn Feiners’ were engaged in treachery against their men folk who were fighting at the fronts. Ernie O’Malley heard one woman shout at the rebels in the GPO, ‘you dirty bowsies, wait till the Tommies bate yer bloody heads off”, “If only my Johnny was back from the front you’d be running with your bloody well tail between your legs’.[11]

Another probable cause of friction during Easter week was the fact that many inner city residents saw their workplaces – such as Jacobs’ factory – and hospitals such as the South Dublin Union – taken over by the insurgents, leading to the rebels being heckled by a t least one onlooker as, ‘starvers of the people’.[12] And on top of that, they made the city a battlefield for the week, endangering the lives of all residents and their families.

The Separation women were not unionists as the term is conventionally understood, though throughout the war years in Dublin, Cork and elsewhere they would often parade behind the Union Jack. Their ties and loyalties were essentially personal and familial rather than political. There may also have been a class element to the mutual antagonism between them and the Volunteers.

A Volunteer and indeed a Citizen Army member, had to pay monthly dues to the organisation and to pay for his own weapons and uniform. This meant that the average fighter in 1916 or republican activist generally had some disposable income, signifying that, even if they were only skilled workers, they were generally a social step above the Separation women.

This social gulf also helps in part to explain the language the Volunteers used about those hostile to them – ‘scum’, ‘rabble’, ‘slum dwellers’ and so forth. The actions of ‘the rabble’ in 1916 appeared to confirm that the slum population were unprincipled, de-nationalised, vicious and easily bribed, an assessment that tells us as much about the radical nationalists as it does about the Separation women.

The end of the War and the 1918 election

What some of the popular hostile reaction to the Rising appears to show is a gulf between the separatist, or as they more commonly called themselves after 1916, republican movement and the poorest sections of the working class.

And certainly the hostility between the Volunteers and the Separation women outlasted the Easter Rising and even the Great War.

The First World War ended on November 11, 1918. Michael Collins, by now a senior IRB and Volunteer leader in Dublin reported serious rioting between republican activists and British troops. He wrote, ‘as a result of various encounters, there were 125 cases of wounded soldiers treated at Dublin Hospitals that night… Before morning, three soldiers and one officer had ceased to need any attention and another died the following day’. [13]

Throughout the First World War there was hostility between the Irish Volunteers and a section of the working class population. But it did not seem to influence the result of the general election of 1918.

However the memories of other republicans in the city were different. Bernard McAllister, a Volunteer officer from Fingal recalled that the end of the war was marked not only by fights with the British Army, but with the Separation women too;

‘On November 11th 1918, the screaming of sirens and the pealing of the chimes of Christ Church Cathedral announced the armistice. As if at a signal, Grafton Street became bedecked by Union Jacks. Crowds of separation women – the women who were drawing separation allowances because their Husbands were in the British forces – poured into the streets and formed processions headed by the union Jack. In a little while it became, less en expression of thankfulness for peace than a jingo demonstration against Sinn Fein in Dublin.

The mob went on to attack Sinn Fein headquarters at No. 6 Harcourt Street;

A dance crowd, singing British war songs, collected, in front of Sinn Fein headquarters and attacked the building. The police made faint-hearted efforts to disperse the mob, which grew larger by the hour. In the evening, reinforced by many hundreds they attempted to set fire to the building. A section of the third Battalion of the Volunteers was called out to defend the building and a very lively fight ensued. The Volunteers saved the building and extinguished the fire, beating back the attackers. A few companies of British military then came along and occupied the street. [14]

A Cumann na mBan activist, Eillis Bean Ui Chonail, was also in the building that night;

‘There were many Volunteers in the building at the time including Harry Boland and Simon Donnelly who took over command. They immediately started to barricade the front a door and windows with chairs and other furniture. Soon we found ourselves hauling chairs, etc., and stacking them up against the windows and helping the Volunteers generally. Shots rang out, mingled with vile language and shouts of “God save the King!” A state of terror reigned over the whole neighbourhood until a late hour when the crowds dispersed’.[15]

Similarly in Waterford, during the campaign for the general election that was called for just a month after the war’s end, Sinn Fein activist Dennis Madden found the relatives of soldiers, whom he called ‘The [Irish Parliamentary] Party rabble’, on the side of the Redmondites;

When I came back to Waterford in August 1917, the place was seething with pro-British flunkeyism, the separation money, and all the relatives at home, and the overall influence of Redmond and his A.O.H. [Ancient Order of Hibernians] bosses. Drink was cheap, and was flowing day and night. The Peelers [Police] gave the blind eye to all the aggressions of the party rabble. Degeneracy reached its crescendo during the General Election of 1918. Money was spent on drink and the mobs were inspired to throw bottles and stones. “Bottle for bottle and stone for stone” said Peter O’Connor off a Redmondite platform. [16]

All over the country there were clashes between Sinn Fein and Volunteer activists on the one hand and the Separation women and their families, on the side of the Redmondites, on the other. We might expect therefore that the results of the election to show a substantial vote among poor and working class communities for the Irish Parliamentary Party, which had supported the War and by extension their relatives serving in it.

The 1918 election was the most democratic ever up to that point in Britain or Ireland. All adult men over 21 and women over 31 (though subject to some property restrictions) had the vote. Under the new franchise the electorate in Ireland was almost tripled, from 700,000 to over two million. [17]

However the results failed to show any significant correlation between low social class and votes for Sinn Fein, who swept the polls in Dublin with the exception of the upper class unionist constituencies of Pembroke and Rathmines.

A number of caveats are necessary. The separation women did not have the vote in 1918 due to the remaining property restrictions on women voters. Men serving in the armed forces could vote by post but few did so – their turnout was only 27%.[18] And perhaps there was a working class Redmondite vote for Alfie Byrne a populist IPP candidate who got a high vote in the working class Harbour constituency of Dublin, though he failed to get elected (he re-took seat as an independent 1922 and later served as Lord Mayor of the city).[19]

Having said all this, it is still clear that most working-class voters in Dublin and by and large elsewhere in Ireland also with the exception of Ulster, gave their vote in 1918 to Sinn Fein. Which leaves us with two possible conclusions; first the Separation women and their families were never really representative of their communities or second, between 1916 and 1918 the republicans did enough to win over previously hostile working class people.

How did the separatists win over the slums

The first thing to note is that inner city Dubliners not only rioted against the separatists but also on many occasions rioted with them against the British Army and Dublin Metropolitan Police.

Before the First World War, the IRB newspaper Irish Freedom praised the Dublin ‘mob’ as good patriots, arguing that they were, ‘not anti-Irish or indifferent to politics, but ill-educated’. The working class rioter, ‘cheers nationalists and harasses the police’. ‘It is great to find that our people’, they wrote, ‘recognise that the police are the greatest enemies of Ireland’.[20]

The first anniversary of the Easter Rising in 1917 was marked by a riot on O’Connell Street in which a republican tricolour was hoisted over the ruined GPO and another over Nelson’s pillar, ‘That was the signal’, the Irish Times reported, ‘for an outburst of cheering and various other demonstrations of approval on a wide scale’. When the police, after some effort sawed down the temporary flagpole, they were stoned by inner-city youths. The police had temporarily to retire from the north inner city as what the Irish Times sniffily called ‘young toughs’, looted shops, damaged a Methodist Church and overturned several trams. [21]

In other words, ‘the rabble’ was sometimes pro-republican, before during and after 1916.

Some working class people were already sympathetic to republicans. Others were won over by campaigns of social activism and against conscription in 1916-18.

Probably more important in the republicans’ winning over the working class as well as the general Irish population however was the growing discontent in Ireland caused by the War. In particular, wartime inflation drove rising food prices leading to increasing hardship for the poor.

At the Dublin docks, the local Volunteers gained much of their mass appeal in 1917-18 by seizing and slaughtering animals set to be exported and instead distributing the meat among the poor. A young Volunteer named Charlie Dalton was given tea by grateful locals, whom he had watched do the same for ‘British Tommies’ marching off to war in 1914. ‘We were now’, he recalled, ‘the heroes of the people’. [22]

Similarly, another republican, Laurence Nugent recalled that both trade unionists and republicans resisted the export of food from Dublin to Britain;

Essential foodstuffs were very scarce and prices were prohibitive. Still the exports to England were increasing. Then on April 17th the dockers at the North Wall refused to load foodstuffs for England. This action relieved the scarcity in Dublin. The food position in Ireland during the years 1917, 1918, 1919, 1920 and most of 1921 was really bad. Butter, eggs, bacon, sugar and other foods were almost unobtainable. At the same time great quantities were being shipped to Britain under the British food control orders. [23]

Republicans, especially the women in Cumann na mBan, also did voluntary social work in this period, including helping to set up free hospitals during the influenza epidemic of late 1918. (more on this here)

Nugent thought that the Volunteers or IRA in Dublin in the subsequent War of Independence was built on the poor;

During this period of the fight for freedom the Dublin and Irish working man or artisan, shop assistant or small farmer’s son had no allegiance for any party only the independence party. These were the men who carried out the fight, often under great hardships and privations to themselves and their families. The I.R.A. was composed from them. How they existed during the lengthy strikes and long stretches of unemployment, along with the exorbitant prices which they had to pay for food, is still a mystery, but they carried on and never complained.[24]

Nugent was of course probably exaggerating. As we have seen there was substantial working class identification with Irish participation in the war and hostility to the republicans. But events of the spring of 1918, when the British government attempted to extend conscription to Ireland, seem to have killed off any remaining support for the war effort and was pivotal in Sinn Fein’s success in the election of 1918.

By this time economic recruitment had long passed its peak. Recruiters in Cork city for instance noted that, ‘the labouring class, which has supplied all the recruits up to the present, is now exhausted and very few more may be expected from this quarter’… No material advantage is to be gained by enlisting. The available men are mostly unmarried, so the separation allowance is no inducement’.[25] Most likely the same was true in Dublin and elsewhere. Even those who had supported Redmond and the war in 1914 felt that Ireland had already given enough.

Moreover national resistance to conscription, supported by all nationalist parties the trade union movement and the Catholic Church, but led by Sinn Fein, produced an impressive popular mobilisation. The Irish Trade Union Congress called a General strike in April 1918, which was universally observed in working class Dublin. Parades of slum women – the very same constituency as the Separation Women, signed a solemn pledge not to take the job of any man who was conscripted.[26] In Cork city the Separation women were noted to have taken part in the anti-conscription rallies.[27]

If there was a tipping point in which the separatists won over the slums, the conscription crisis was most likely it.

Epilogue

The hostility between radical nationalists and the families in particular the women of serving soldiers was a marked and widespread feature of political life in Ireland from 1914 to 1918.

Republicans were seen as traitors and malcontents by sectors of the working class population and the sentiment was more than reciprocated by the separatists for the pro-British ‘rabble’.

This confrontation, generally speaking, does not seem to have long outlasted the war, however, and republicans were able to take advantage of rising social discontent from 1916 to 1918, as well as the fallout from the repression of the Easter Rising and the postponement of Home Rule to win widespread working class support in the election of 1918.

The end of that year, while the end in the main of overt clashes between separatists and ‘Separation women’ may not entirely be the end of the confrontation between the Republicans and Irish ex-servicemen. In the War of Independence 82 out of the 200 people shot as spies were ex soldiers [28] and in the Civil War the Free State’s National Army recruited heavily from the pool of ex British soldiers and the Dublin working class.

The Free State was highly socially conservative and did little in its early years to solve the problems of poverty and housing in the cities and in Dublin particular. Against this background, Republicanism, defeated in the Civil War of 1922-23, at times played the role of expressing social and as well as national discontent.

What does seem clear though is that the Separation women and their families left no lasting political legacy. Above all the conscription crisis of 1918 showed that there was little enthusiasm in Ireland about dying for the Empire.

In the end though, what we have left to piece together about the separation women are merely echoes of their words, recorded by those for whom they were not fellow Irish citizens, but simply, ‘the rabble’.

References

[1] Bureau of Military History (BMH) WS Thomas McCarthy, Captain IV, Dublin, 1916 Roe’s Distillery 1916

[2] BMH WS Sean Kennedy, Lieutenant IV, Dublin, 1916; IRA, 1921, Four Courts 1916

[3] Geraldine Dillon, sister of Joseph Plunkett Cumann na mBan GPO 1916. BMH WS 358

[4] BMH WS 147 , Bernard McAllister, Officer IV and IRA, Fingal, 1913 – 1921

[5] All above figures from Padraig Yeates, Dublin 1914-1918, A City in Wartime, p7-11

6 Yeates, A City in Wartime, p47

[7] Ibid. P48

[8] Ernest Blythe Witness Statement BMH

[9] John Borgonovo, The Dynamics of War and Revolution in Cork, 1916-18, (2013) p64

[10] Michael Sheehy, BMH WS 989

[11] O’Malley, On Another Man’s Wound, p39

[12] Fearghal McGarry, The Rising, Ireland Easter 1916, p252

[13] Peter Hart, Mick, the real Michael Collins, p203

[14] BMH WS 147 , Bernard McAllister

[15] Eilis Bean Ui CHonaill WS BHM

[16] Dennis Madden BMH WS 1103

[17] http://www.ark.ac.uk/elections/h1918.htm

[18] Borgonovo, Dynamics of War and Revolution, p228

[19] The results in the Dublin constituencies can be viewed here http://electionsireland.org/results/general/01dail.cfm

[20] Irish Freedom, September 1911

[21] Yeates, A City in Wartime p191-192

[22] Yeats, A City in Wartime p227

[23] Laurence Nugent WS 907

[24] Laurence Nugent WS 907

[25] Borgonovo, Dynamics of War and Revolution, p186-187

[26] Yeates City in Wartime p234-236

[27] Borgonovo, Dynamics of War and Revolution, p194

[28] Coleman, Longford and the Irish Revolution, p154