Opinion: Remembering World War I in Ireland

An opinion piece on Ireland, the Great War and its memory. By John Dorney. For more articles on WWI and Ireland see here.

An opinion piece on Ireland, the Great War and its memory. By John Dorney. For more articles on WWI and Ireland see here.

In the south Dublin where I grew up, in the 1980s and 1990s, the First World War was strangely present.

I went to cub scouts in the Rathfarnham War Memorial Hall, built-in 1919, where the names of the local Church of Ireland parishioners who had died in the Great War looked down on us from wooden plaques on the walls as we practiced tying our neckerchiefs and competed for badges.

I remember walking around the rather ghostly, though recently restored War Memorial Gardens at Islandbridge as a twelve-year-old, which to me had the feeling of a deserted cemetery – dedicated to the ‘49,400’ Irishmen who fell in the Great War. The number is in fact too high, of which more later. The point is, it emphasized ‘a great number’.

As a boy I was fascinated by military history and even managed to persuade my parents to take me on one of our camping holidays to the Somme battlefield at Thiepval, where I clambered across the remains of trenches and we stood gazing at the enormous arched monument to the British and Commonwealth dead.

A little later on, in my secondary school (again Protestant) there were plaques and stained glass commemorating the ‘old boys’ who had died in the Great War (and to a much smaller number who had died in the Second). In November, prefects would carry around British Legion poppies for students to buy. Even for my thirteen or fourteen year old self though, this was a step too far.

It was one thing to be aware of the war as history, quite another to suggest that it was a good idea to fight in it. Like most of the school’s vestigial unionist heritage, selling poppies was a little half-hearted, ritualistic almost, done because they had always done it rather than out of some burning conviction. They also had a copy of the Easter rebels’ Proclamation of the Republic in 1916 inside the front door.

But still, it made me angry. The War had been an enormous slaughter for no appreciable reason. None of the books I could find in the library could explain adequately why it started or what the point of so much carnage was. If it was a war for ‘our freedoms’, how come it was fought by Empires – British French, Russian, who had conquered innumerable small countries? And there was something else. It was not ‘our’ war. Irishmen had not died for Ireland, but as cannon fodder for the British empire. I used to explain this forcefully to any prefect who asked me to buy one. This was not always appreciated.

It is of course the simplest form of nationalism and also of teenage self expression –‘your symbols are not ours. We reject them. We have our own’. We are not British we are Irish. Those who suggest otherwise, or that the two are compatible, are traitors. To promote the idea of Irishmen in the British Army is to suggest that Irish independence is wrong.

These emotions of my teenage years are with me still. Emotionally I still feel essentially that Irish involvement in the First World War should not be commemorated as anything other than a senseless tragedy. I cannot quite shake the feeling that those who wish to celebrate the slaughter of Irish people (and million of others) for no discernible political objective at back simply like the idea of the people rowing in behind whatever the power elite tell them to do.

But part of growing up is learning to see that how one feels about something is not the same as objective truth about it.

And in recent decades, there has been a substantial movement in Ireland towards recognizing and reclaiming the memory of Ireland’s involvement in the Great War.

Revising Irish memory of the Great War.

There are a number of versions of this trend. One is simply the recovery of family history such as the books and websites dedicate to naming the county war dead.

An interpretation of Irish experience of the Great War is that Irishmen volunteered in great numbers in 1914 for what they believed to be a noble cause and died in great numbers. They returned to Ireland to be reviled as traitors, targeted as ‘spies’ by republican guerrillas and their memory ‘airbrushed out of history’

Another is to suggest that Irish involvement in the War showed that another path may have been taken in Irish history – the path of constitutional nationalism, of John Redmond and the Irish Parliamentary Party, who encouraged Irish nationalists to join the British forces to secure Home Rule and to come back as an Irish Army – rather than violent and exclusive republican revolution.

Part of the motivation for this has been antipathy to modern republican violence, but also for many the frustration with the stifling nationalist and Catholic orthodoxy with which they grew up in the 1950s and 60s and its association with the economic shortcomings of the 26-county Irish state.

Yet a third interpretation seeks to use the shared experience of nationalist and unionist soldiers in the trenches as a tool of reconciliation, particularly in the North of Ireland. Alex Maskey, for instance the Sinn Fein mayor of Belfast in 2002 visited the Somme battlefield and in Belfast laid a wreath in honour of his ancestor who had died there. Sometimes this version (admittedly not Maskey’s) contrasts the supposed heroism of the First World War soldiers, who ‘fought fair’ with the cowardly paramilitaries back in Ireland who ambushed, assassinated and killed the defenceless.

The narrative of this interpretation of Ireland’s involvement in the Great War goes something like this; Irishmen volunteered in great numbers in 1914 for what they believed to be a noble cause – freedom of small nations, Home Rule for Ireland, resisting German militarism – and died in great numbers. They returned to Ireland to find that the political agenda had been hijacked by the rebels of 1916. They were subsequently reviled as traitors, targeted as ‘spies’ by republican guerrillas and their memory ‘airbrushed out of history’ – a phrase repeated ad naseum on this topic – in the independent Irish state.

Whatever one might feel about it, does this interpretation stack up with the historical facts?

A noble cause

In August 1914,Britain declared war on Germany and its allies. Arguments continue to rage over whether this was to preserve the independence of small states or counter balance German power or simply out of economic and strategic self-interest.

Regardless, Irishmen did join the British Army in very large numbers in 1914. A total of 206,000 Irishmen served in the British forces during the war. [1] The recruitment rate in Ulster was as high as in Britain itself, Leinster and Munster were about two thirds of the British rate of recruitment before conscription, while Connacht lagged behind them.[2]

Some of this was indeed politically motivated. Unionists north and south had a fairly clear motivation; to defend the Empire with which they identified. Some 26,000 recruits came directly from the Ulster Volunteers – the unionist militia founded in 1912. But initially Irish nationalists too supported the war.

Irish Parliamentary Party (IPP) leader John Redmond told his Irish Volunteers that they would be serving Ireland by joining, up, that the Irish Divisions raised by Kitchener’s New Army would be the basis of an independent Irish Army under Home Rule. And that self government would be granted if Ireland played its part in the war effort. Much play was also made of the justice of this cause, to protect the independence of small nations like Belgium, whose sovereignty was violated by German invasion in 1914.

And there is no doubt that in 1914 Redmond won the arguments within Irish nationalism. The Irish Volunteers – the nationalist militia formed in 1913 – split but the vast majority, 150,000, followed Redmond into the pro-war National Volunteers, compared to 10,000 who remained in the anti-war Irish Volunteers. In 1914 Redmondite MP Stephen Gwynn exulted that the radical nationalists were, ‘snowed under and I think were almost dumbfounded by what they found around them. They held no meetings and had no press’.[3] (Though one reason why the ‘Sinn Feiners’ had no press was that titles such as Irish Freedom of the IRB and James Connolly’s Irish Worker were closed down and their presses seized under the Defence of the Realm Act for anti-war agitation.)

Redmondite National Volunteers were a small minority among those who joined the British forces, apolitical factors such as unemployment and desire for adventure were more important than political factors.

Nor is there any doubt that many nationalist recruits did believe what Redmond told them. Irish Party stalwarts such as Thomas Kettle and Redmond’s own brother Willie served and died in the war. And there are smaller examples too; a Celtic Cross monument stands in the little town of Castlebellingham, County Louth, for instance, dedicated to, ‘those who died for Irish Freedom in the Great European War, 1914-18′ . Ernie O’Malley, the future IRA leader and writer, whose family were moderate nationalists remembered getting into a fist fight with separatists in Dublin who tried to seize his Union Jack coloured hooters in 1914. [4] His older brother Frank went on to serve as an officer in the East African campaign, in which he died.

But idealistic recruitment accounted for a minority of Irish enlistment. Many had already been career soldiers for whom politics did not come into it. Of those Irishmen who served in British forces in the war; 58,000 were already enlisted in the British Regular Army or Navy before the war broke out.

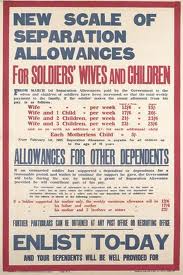

Of the 140,000 men who were volunteers recruited for the duration of the war, only 24,000 originated from the Redmondite National Volunteers and 26,000 from the loyalist Ulster Volunteers.[5] Therefore only about 12% of Irish servicemen had come directly from Redmond’s political base. Out of the remaining 80,000 who had no experience in either of the paramilitary formations, most were urban and poor. In Dublin City, a survey of 169 recruits from Corporation workers shows just 9, ‘salaried professional’ workers joining up and 113 unskilled labourers – for whom the Army signified a pay rise and a chance to learn a trade. ‘Separation money’ paid to their families was another incentive. [6] Farmers and their sons were under-represented across the country. In county Galway, police reported that recruiting was, ‘slow and entirely confined to the towns’.[7]

Economic motivation played a significant part, as it did in Britain itself (voluntary recruiting there slowed when the war economy began to offer more jobs). Other recruits simply liked the idea of being part of something big and important. Tom Barry famously wrote, ‘I went to the war for no other reason than that I wanted to see what war was like, to get a gun, to see new countries and to feel a grown man’.[8] In short, most Irishmen joined up not to attain Home Rule, nor to prevent it, to fight for small nations or defend the Empire, but much more commonly for a range of apolitical reasons.

By 1915, Irish public opinion was already wavering on the war. In November of that year, 700 Irishmen trying to emigrate to the US were blocked at Liverpool on the basis that they should be in the Army. Redmond remarked that it was, ‘very cowardly of them to emigrate’ rather than enlist – provoking a hostile public response from, of all people, a Catholic Bishop, O’Dwyer, ‘Their crime is that they are not ready to fight for England. Why should they? What have they or their forbears ever got from England that they should die for her?’.[9] Recruitment slackened when it became clear there would be mass casualties in the war and did not revive thereafter.

Well before the war was over, most Irish people had turned against it, for political and economic reasons but also through fear of conscription

By 1916, when conscription was imposed on Britain to fill the gaping holes left by hundreds of thousands of casualties, opinion across the board in Ireland, unionist as well as nationalist, was against it being extended to Ireland. The Easter Rising and its suppression is therefore only one part of the story of the turn against the war. It was the campaign against conscription that really made the new Sinn Fein party and buried the IPP – which although it opposed conscription was popularly associated with the British war effort. There was no appetite for total war in Ireland and there was also a conviction that Ireland’s contribution was not really appreciated in Britain anyway.

There were also social reasons for the turn against the war. Peter Hart tracks, for instance, the closing down of the Congested Districts Board, which supervised land reform, for the war. The most land hungry regions, in the west and north midlands, were also those which turned most heavily to Sinn Fein after the Rising. Similarly, rising prices and taxes during the war led to a strike wave and the rise of labour as a political force.

Moreover, it was already plain by then that version of ‘fighting for Ireland’ promoted by Redmond was no longer credible. Home Rule – which was a very limited form of self-government in any case – could not be implemented except by the partition of the country in the face of unionist resistance. The Irish Divisions, the 10th and 16th Divisions, very far from being a proto-Irish Army – were officered by British officers and filled at a fairly early stage with recruits from elsewhere.[10] By contrast the 36th Ulster Division, recruited in large part from the UVF, kept its own officers and political identity – a clear sign that Irish nationalism was still distrusted by the British Government.

The political conflict that began with the insurrection of 1916, with its subsequent rounds of rioting and arrests played its role too in undermining support for the war. By 1918, Arthur Lynch, a nationalist MP who had joined the British Army with a rank of colonel, was shouted down every time he tried to speak in favour of recruitment in Dublin. He told a crowd, ‘I have endured great trials and faced great dangers in the cause of Home Rule’. A heckler asked, ‘why not stop in Ireland and share our dangers?’[11]

Spies and traitors?

Irish losses in the War were certainly great, but the oft-cited figure of 50,000 deaths is too high. This figure refers to all those in the Irish Divisions who lost their lives, but these Divisions were composed not only of Irishmen. The British registrar general recorded 27,405 deaths among those soldiers born in Ireland, a casualty rate of 14%, roughly in line with the rest of the British forces .[12]

Experience of war was a very common social fact in Ireland in 1918. Something like 30% of men of military age had been through it. The burden of grief caused by death or injury was spread very widely. But the Redmondite idea that to fight for the Empire was also to fight for the freedom of Ireland had been quite discredited by the end of the war and was one of the main reasons why the Irish Party lost the 1918 election so disastrously. The young were increasingly attracted to another vision of fighting for Ireland, one pioneered by the rebels of 1916.

Many Irish war veterans were proud of their service, proud of what they and their friends had been through together but did necessarily identify this with support for Britain in Ireland. Such loyalist feeling was largely confined to unionists. The ex-servicemen’s association in Cork for instance, formed their own organization in order to be independent of the Royal British Legion. Their demonstrations were often stewarded by the Irish Volunteers or Republican Police and in 1920 they were involved in bloody rioting against the British Army in the city after one of their members was shot dead by British troops.[13]

Most war veterans were not targeted by the IRA but there is some evidence for conflict between Redmondite war veterans and the Volunteers post 1918

Were the war veterans targeted by the IRA as ‘spies’ in the ensuing bout of political violence known as the War of Independence and Civil War? Before going into details, it its worth restating how common service in the war had been, across virtually all political tendencies except those who were separatist or republican activists. To target war veterans en masse would have meant huge massacres and nothing like this occurred.

Some war veterans joined the guerrillas of the IRA and provided valuable military training. Tom Barry, who ended up commanding the West Cork IRA flying column is the most famous example but there were many others, notably Emmet Dalton, who was accepted into the inner circle of Michael Collins’ Squad and later became a senior National Army commander too.

However, there is also evidence that some republicans viewed those who had served in the British Army as traitors. The 1918 election saw fierce rioting between Sinn Fein and IPP activists in some constituencies and across the country the republicans tended to blame ex soldiers. In Waterford city for instance, where the Redmondites held onto the seat, a republican activist reported; “Redmondite mobs, mainly composed of ex-British soldiers and their wives…carried on in a most blackguardly fashion, Anybody connected with Sinn Fein was brutally assaulted with sticks, bottles etc”.[14] In Clare, where Sinn Fein had Eamon De Valera elected, it was the same story, according to one republican’s memory, the ex British soldiers were, “like lunatics, attacking with knives and heavy sticks”.[15]

Out of 200 people killed as informers in the War of Independence, 82 were war veterans

Moreover, the IRA shot dead some 200 civilians as alleged informers in 1919-21 and no fewer than 82 of these were ex-servicemen.[16] Some of this may be explained simply by the demographic probability of ex soldiers, many of them out of work, being recruited as informers by Crown forces. But it does seem that unless war veterans were actually friendly to republicans they were targets of suspicion at least.

To some degree therefore, the 1914 split in Irish nationalism over the First World War did persist. In the north especially, where the IPP held its own against Sinn Fein, there was some competition between the IRA and Catholic ex-servicemen aligned with the Ancient Order of Hibernians and the Irish Party, over who should provide armed defence of the Catholic community, especially in Belfast, from loyalist attack. The IRA only definitively wrested control of nationalist streets in that city in early 1922 when the new Dublin Provisional government began funneling arms and money their way. [17]

At the outbreak of the Civil War in 1922, when the Free State appealed for volunteers to join its National Army and put down those republicans who threatened the Treaty settlement, a very large percentage of the 58,000 civil war recruits (at least 30%) were veterans of the British Army. This may have been an apolitical choice for many, unemployment was again high and the National Army offered a wage and accommodation but republicans certainly made much of it in propaganda and ex-soldiers may have seen it as a chance to get revenge on their tormentors of 1919-21.

In the post-independence period, the remains of the IRA made a practice of disrupting Remembrance Day commemorations in Dublin, and beating up poppy sellers and seizing Union Jack flags. But again they argued that they were not against ordinary Irish veterans commemorating their dead but those who would use it to promote ‘imperialism’ in Ireland. An Phoblacht wrote in 1925, ‘no republican wishes to mar the solemnity of their commemoration. We too know what it is to lose well loved comrades who fought by our side…but there is another side to this story, there is a small but noisy section of the British garrison which seeks to turn each Armistice day into an occasion of imperialist propaganda’.

In particular they objected to the presence of the British Fascisti, who appeared at Remembrance Day ceremonies in the late 1920 and early 30s.[18] Police were used to protect Remembrance day participants but disturbances petered out once the ceremonies were changed from the city centre to the Phoenix Park.

In short, ex-servicemen’s experience in post-1918 Ireland was extremely varied. Some were unionists and served in the Ulster Special Constabulary. Some others became republican fighters. Some retained their allegiance to the IPP. Many others simply tried to pick up their lives where they left off. Ex servicemen were not subjected to systematic attack or discrimination but some were indeed the target of republican violence on occasion.

Airbrushed out of history

Finally, were the Irishmen who served in the First World War ‘airbrushed out of history’?

Again, if we are to be fair about this, we must be nuanced. Republicans, particularly the losing anti-Treatyites of 1922-23 were certainly hostile to the promotion of their cause.

Far from ‘airbrushing them history’, the first Irish governments paid generously for memorials to the dead of the Great War, though they stopped attending ceremonies after 1932

But the Irish government in fact generously funded war memorials to the Irish war dead – £50,000 in 1926 to fund a War memorial Park in Dublin and another £25,000 to maintain Irish War Graves in France and Belgium. Anne Dolan in her study of commemoration in Ireland found that the Free State government of 1922-32 was most reticent about building monuments to those who had died in Free State uniform in the civil war but relatively forthcoming with funds to commemorate the (admittedly much more numerous) dead of 1914-18.[19]

Republican monuments were funded primarily not by the state but by the voluntary body the National Graves Association. One reason for this, that also says something about the often false anti-British rhetoric in independent Ireland, was that anti-Treaty Republicans remained a danger to the southern state while some of its most important financial backers were the bankers in the Bank of Ireland, and industrialists such as the Guinness and Jameson families who had all been unionists and who had lost family and friends in the Great War.

‘The State has other origins and because it has other origins, I do not wish to see it suggested, in stone or otherwise, that it has that origin’, Kevin O’Higgins 1926

It is worth noting here that while the [Great] War Memorial Gardens in Islandbridge were completed in 1948, it was not until 1966 that the Irish state built a memorial, the Garden of Remembrance, to commemorate those who had died in pursuit of Irish independence.

Padraig Yeates makes the point that, ‘far from being forgotten, thousands attended the annual Armistice Day commemorations in the Phoenix Park for decades. Free State ministers attended ceremonies in Dublin and London until Fianna Fail came to power [in 1932] and the political establishment turned its back on Remembrance Day. But forty thousand were still reported to have attended the 1939 commemoration….Subsequently as the collective memory receded, so did the numbers who attended the ceremonies… Many families in Dublin with a unionist background continued to commemorate their fallen members within family religious circles. [But] the great majority of Catholic Dubliners who served in the British forces were members of the working class, with no particular allegiance to the Crown or the Union.’[20]

And yet, to some degree it is true that nationalist Ireland regretted its part in the Great War and wanted to forget it altogether. The Cumman na nGaedheal government of the early years of the Free State declined to have a War memorial in Merrion Square, beside government buildings, instead sticking it out of the city centre near the Phoenix Park. To do otherwise would be suggesting that Irish self-government had been won in the trenches and the Redmondites had lost that argument for good. Kevin O’Higgins, the bête noir of republicans, who once declared that not only did he defend the executions of 77 republicans in the civil war but that he would execute another ‘777 if necessary’, and whose brothers had served in British uniform, summed up the mainstream nationalist verdict on the Great War in 1926. Speaking about the proposed park in Merrion Square, he said;

‘I say that any intelligent visitor, not particularly versed in the history of the country, would be entitled to conclude that the origins of this State were connected with…the memorial in that park [Merrion Square] and the lives lost in the Great War in France, Belgium, Gallipoli and so on. That is not the position. The State has other origins and because it has other origins, I do not wish to see it suggested, in stone or otherwise, that it has that origin’.[21]

The First World War was a calamity that not only killed some 10 million people, but also smashed the old order in Europe, shredded European economies and led directly to the rise of fascism and communism. It also helped to discredit British rule in Ireland. Well before the war was over, most Irish people regretted that John Redmond had promised nationalist support for the war effort. He and his party paid the price in 1918. War service was commemorated thereafter but celebrated only by the minority of former unionists in the Free State.

If people today want to wear a poppy, they should of course be free to do so, without harassment or intimidation of any kind. Historians must acknowledge the war’s importance in Irish history. It is entirely appropriate for families and localities to remember their dead. But to suggest that war for the Empire was popular in Ireland and only discredited by a malevolent plan by nationalists to ‘airbrush it from history’ is simply to twist the facts.

References

[1] Fergus Campbell, Land and Revolution, Nationalist Politics in the West of Ireland 1891-1921, p196

[2] Charles Townsend, 1916, The Easter Rising, p65

[3] Townshend p73

[4] Ernie O’Malley, On Another Man’s Wound, p29

[5] David Fitzpatrick, Militarism inIreland 1900-1922, in Thomas Bartlet, Keith Jeffrey, ed. A Military History of Ireland, p386

[6] Padraig Yeates, A City in Wartime, p47

[7] Fergus Campbell, Land Revolution, p197

[8] Tom Barry, Guerilla days inIreland p

[9] Townshend, p79

[10] Townshend, Easter Rising p75

[11] Yeates A city in Wartime, p251

[12] Fitzpatrick p392

[13] William Sheehan, A Hard Local War p26-30

[14] Annie Ryan, Comrades, Inside the War of Independence, p222.

[15] Padraig Og O Ruairc, Blood on the Banner, p63

[16] Marie Coleman, Longford and the Irish Revolution, p154

[17] Robert Lynch, The IRA and Early Years of partition, p85-86

[18] Fearghal McGarry, ‘Too Damn Tolerant, Republicans and Imperialism, in Republicanism in Modern Ireland, pp56, 77

[19] Anne Dolan, Commemorating the Irish Civil War, p130-145

[20] Yeates, ACity in Wartime, p301

[21] Anne Dolan, p188, Commemoration, in The Irish Revolution 1913-23