A stroll through Jewish Dublin

A glance at part of Dublin’s past and present, by John Dorney.

A glance at part of Dublin’s past and present, by John Dorney.

The South Circular Road in Dublin looks like what you’d imagine a city to be. All red brick and character. Wrought iron railings and gargoyle heads on houses. A friend of mine, referring to the iron fire escapes on the gothic-style buildings, once remarked that it looks more like Old New York than inner-city Dublin.

Constructed for the most part in the late 19th century, the Road curves from working class Dolphin’s Barn, with tight-packed red-brick terraces and the odd, more modern flat complex, along the canal as far as leafy, tree-lined Adelaide Road with it’s Victorian town houses, complete with servants’ entrances.

Today as you stroll along it you will see all kinds of Dublin life. The solicitor’s offices, the blue-uniformed boys coming out of Synge Street Christian Brother’s school, but increasingly you’ll also see people of many and varied nationalities, walking, shopping, pushing their young children in prams.

On the street corners, especially on Fridays you will find young Arab men in the cafes, talking loudly but companionably in that way that Arabic speakers seem to have. Walk past the former barracks and the rather misleadingly named National Stadium (for boxing) and you will spot the crescent of the Dublin Mosque rising over the red-brick terraces.

On Clanbrassill street there are a line of halal grocery and kebab shops. Modern, multiculturalDublin.

But this has been an immigrant area, where people arrived and staked out their community’s place in the city, for a lot longer than the 15 odd years of the (now sadly departed) economic boom in Ireland. Just across the road from the Dublin Mosque is a solid columned building. On closer inspection, the blue railings at the front are wrought into five pointed stars, as are the designs in the windows. This was once one of six synagogues in an area then known as ‘Little Jerusalem’.

The late 1800s has been called the world’s first era of globalization. New modes of transport, free trade across borders and massive movement of people, both within and across states transformed the western world. Irish people, of course, crossed the Irish sea and the Atlantic to labour in the cities of Britain and North America as did Italians, Poles and Germans. At the same time, however the great tide of human movement washed up another small community in Ireland.

The late 1800s has been called the world’s first era of globalization. New modes of transport, free trade across borders and massive movement of people, both within and across states transformed the western world. Irish people, of course, crossed the Irish sea and the Atlantic to labour in the cities of Britain and North America as did Italians, Poles and Germans. At the same time, however the great tide of human movement washed up another small community in Ireland.

In the 1870s, a small number of German Jews pitched up in Dublin. By 1881, the community numbered about 450.

The first age of globalisation washed a small Jewish community up on Ireland’s shores

They were followed from the 1890s by another, larger wave of Jews from what were then the Baltic provinces of the Tsar’s Empire – modern Latvia and Lithuania. By 1901 the Jewish population of Ireland was about 4,800, of whom most lived in Dublin.

The largest Jewish community in the world from the middle ages until the 1940s was in the lands controlled by the Russian Empire, where they were subject of various kinds of discrimination. In 1882, for instance the Tsar passed laws forbidding Jews from living outside towns, buying land or entering the professions.

As soon as it became practicable, many Jews in the Tsar’s Empire packed up and headed west. Most went to places such as France, England, and most of all North America, but also, in small numbers, to Ireland. The Levitas family, for example made their way to Dublin from Lithuania and Latvia fleeing the anti-Semitic pogroms of Tsarist Russia in 1912

By 1911 some 90% of Dublin’s 4,000 Jews had been born in the Russian Empire

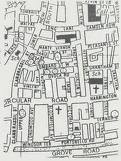

The South Circular Road area, located just south of the old city centre, was at the time , a relatively new area and much of the housing there was cheap and affordable. It may also have helped that the neighbourhood was already religiously mixed. A survey of the neighbourhood in the 1911 census shows that of 1,185 households, 329 were Jewish, 558 Catholic, 219 Church of Ireland and the remaining 79 belonged to other Christian denominations.

By the time of the 1911 census, 80-90% of Dublin Jews had been born in the Russian Empire. Relations between the generation of Jewish arrivals in Dublin was not always smooth. The more cosmopolitan German Jews were a little disdainful of the Yiddish-speaking religiously orthodox new arrivals. Melanie Brown, the curator at Dublin’s Jewish Museum, tucked away in Walworth Street, will tell you with a smile, when asked why a community of some 3,000 needed six places of worship, ‘because the Jews are a quarrelsome people’.

The richer Jews worshipped at a stately, bright building on Adelaide Road, while their more proletarian co-religionists built for themselves the grey, concrete structure that now faces the Dublin Mosque at the other end of the Road, the foundations for which were laid in 1916. In between were many small synagogues, some simply a single room in a terraced house to cater for various shades of religious observance.

As is typical of migrant minorities, Dublin’s Jews rapidly set themselves up in niche economic activities. A plaque on Camden Street commemorates a Jewish tailors’ and weavers union. The socialist James Connolly in 1902 campaigning for his new (and very unsuccessful) Irish Socialist Republican Party, was aware enough of the presence of a Jewish working class to have leaflets printed in Yiddish for their consumption.

Other Jewish Dubliners set themselves up in various small businesses, jewelers, pawn-brokers, bakers, butchers and money lenders. The Bretzel Bakery for instance which still stands on Lennox street was founded in 1870, baking fresh kosher bread. From then until the 1960s it remained in Jewish ownership, passing from the Grinspon family to the Elliman family in 1910.

What the arrivals from eastern Europe must have made of this damp, grey foreign city we can only guess but a poem written by one Myler Joel Wigoder of Lithuania, gives us some idea of the dislocation they must have experienced. In 1931, on his 75th birthday he wrote, “When first inDublin I arrived I shed hot bitter tears, penniless in a foreign land, I faced the coming years”.

In the turmoil of nationalist revolution from 1916 -1923, some Dublin Jews adopted the republican cause as their own but the violence also produced a small number of anti-Semitic incidents

By the turn of the 20th century, the Jewish community was well enough established for it to be used as a backdrop for James Joyce’s famous novel Ulysses – which follows the fortunes of a Dublin Jew – Leopold Bloom – around Edwardian Dublin. Joyce used Bloom as a foil for the nationalist bigot, ‘the citizen’ who angrily asserts that a Jew could never be a real Irishman.

Political anti-Semitism was never important in Ireland but it did, unfortunately, exist on the fringes of Irish nationalism. Around the turn of the century, Arthur Griffith’s Sinn Fein newspaper carried some anti-Semitic material and in the 1940s the Fine Gael TD Oliver Flanagan notoriously remarked that it was time to, ‘rout the Jews out of the country’. (See here for example)

Despite this, in the turmoil of nationalist revolution from 1916-23, Dublin’s Jewish population produced several prominent republican activists. The roll of honour of the Irish Citizen Army, complied after the Easter Rising, records, “A Jewish comrade, A. Weeks” among those who died in its ranks during the rebellion. Another Dublin-born Jew Robert Briscoe, joined the IRA and was heavily involved in smuggling arms for the guerrilla group into Ireland. He went on to be prominent member of Fianna Fail, the party that emerged in 1926 as the new Irish state’s party of government and later served as Lord Mayor of Dublin.

At the same time, the conflict over Irish independence brought weapons into daily Irish life in a way that occasionally threatened Dublin’s small Jewish community. In 1923, just after the civil war, several officers of the National Army, based in Wellington barracks – who had been part of assassination units first in the IRA and then in the Free State’s army, murdered two Jews and attempted to kill several more, apparently in a row over an alleged assault on a woman by a Jewish dentist.

Similarly in 1926, the IRA, flailing about for a new purpose in the wake of its defeat in the civil war, launched a campaign of intimidation in Dublin against money lenders – most of whom were Jewish. The campaign was short lived and the organization denied that it was anti-Semitic but there seems little doubt that it was in part fueled by resentment of the ‘Jew-man’ as moneylenders were unkindly called in working class Dublin.

There was, once the echoes of armed conflict had cleared away and guns removed from political disputes, no more organized anti-Semitism in Dublin. Regrettably, though like other western governments, the Irish one declined to admit more than a handful of Jewish refugees fleeing the Nazi regime in the 1930s and 40s, on the rather unconvincing logic that large scale Jewish immigration would give rise to anti-Semitism.

During the Second World War the Germans, probably mistakenly, bombed Dublin several times from the air. On one occasion, shrapnel from one of their bombs pockmarked the front of the synagogue on the South Circular Road. The damage is still there. No doubt it was simply a coincidence, but it is an eerie reminder of what happened to Jewish populations at German hands elsewhere inEurope.

The Jewish population of ‘Little Jerusalem’ peaked at just over 5,000 after the Second World War, but its numbers declined quite quickly thereafter. For one thing, the community had changed class. A new synagogue in middle class Terenure, far from the city centre and its slums, was opened in 1953. Later generations of Dublin Jews left their artisan roots largely behind them and joined the professions.

Some left Ireland for larger centres of Jewish population –London, the United States, Israel. A Dubliner, Chaim Herzog, once served as president of Israel– as a 7 year old I recall watching his motorcade, flanked by leatherclad motorbike police, whiz down my street on a state visit to the country of his birth.

After the 1950s, ‘Little Jerusalem’ slowly disappeared as Jews moved to suburbs and abroad.

The current Jewish population of the city is about 1,000.

Today, the South Circular Road area has plenty of physical reminders of the days of ‘Little Jerusalem’, but very little actual Jewish presence. The new wave of globalization since the 1990s has washed up new tides of immigrants to the area, many of them, ironically enough Muslims. It is tempting to draw parallels between the two religious minorities – both for instance started off worshipping in a single room of a private house and branched out to set up religious and community outposts throughout the neighbourhood. On Fridays throngs of Muslims, some of them robed and bearded converge on the Mosque for prayers, much as their Jewish predecessors in the same area must have done 100 years ago.

But there are also differences. The Jews in Joycean Dublin were an oddity, the only substantial immigrant group in a predominantly (and after independence increasingly) Irish and Catholic city. Dublin of today is inhabited by a bewildering range of nationalities of whom the Muslims (themselves of very varied origins) are but one. Walk a few minutes from a halal takeaway and you will find a Polish grocery store. As well as Arabic, on a stroll down the South Circular Road you will probably hear some Spanish and Italian and several eastern European tongues.

A city changes and keeps changing. But what gives its soul is its memory.

The best place to start to learn more about Jewish Dublin is Cormac O Grada’s book, Jewish Ireland in the Age of Joyce. For a more personal view see Nick Harris’s memoir, Dublin’s Little Jerusalem.