‘Lives Illuminated’ a glimpse at Irish-Jewish history

By John Dorney

By John Dorney

An exhibition in Stratford College, part of a project by their Transition year students, aided by as Saul Woulfson chair of Jewish Arts and Culture Ireland (JACI), shed a fascinating light on the history of Dublin’s Jewish community.

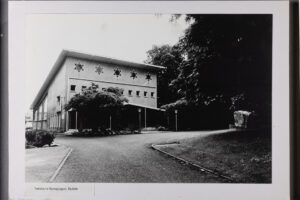

Statford College, locatedin Rathgar on Dublin’s southside, was founded in 1954 to cater for Jewish children, but now caters to students of all faiths and none. Indeed, at an exhibition and presentation on March 30 of this year (2023), it was somewhat endearing to see the schools’ choir filled with students, evidently from all over the world, singing traditional Jewish songs.

The core of the project, entitled ‘Lives Illuminated’, was a series of interviews carried out with people they termed ‘elders’ from Dublin’s small Jewish community and comprises a series of short films, along with an interactive heritage trail and map.

From the Russian Empire to Ireland

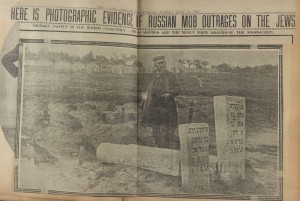

Ireland had a small Jewish presence dating back to the 1700s at least, but the major wave (if a modest movement of people could be described in this way) in Jewish immigration came in the 1880s, after which Jews were for the first time allowed to leave the Russian Empire. Many hundreds of thousands, perhaps millions, did, mostly for western Europe or North America.

The empire of the Tsar was a much larger area than the current Russian Federation, including, among other places, modern Ukraine, part of Poland, Latvia, Lithuania and Moldova and it was these countries that contained by far the majority of the world’s Jewish population at the time. Some, only a fragment of the whole migration, made their way to Ireland. While in 1884, there were a mere 380 or so Jews recorded as resident in Ireland, by the census of 1911 there were 3,800.

Some of the ‘elders’ interviewed traced their family history in Ireland directly back to this time. Heather Abrahamson, for instance, said that in her old age she often wished she had asked her grandparents about those ‘nameless people’, ‘left behind in Lithuania’, now forever lost to her, through time, political turmoil and of course, the Nazi genocide during the Second World War.

David Ross similarly spoke about his family’s candlesticks which had ‘travelled the world’ from Poland, Vilna (now Vilnius the capital of Lithuania), Romania and other places. ‘My family’, he said, ‘is from the whole world’. They initially immigrated to England but left for Ireland to avoid conscription during the First World War (where, though still in the United Kingdom, at that point, compulsory military service was never enforced).

Bertha Cohen recalled that he great, great grandparents came to Ireland from ‘Latvia, Lithuania, Russia, no one knows exactly where’.

It was not entirely one-way traffic form east to west. Eddie Marcus recalled that he and other Irish Jews had in the 1980s visited ‘Russia’ (at that time the Soviet Union) and smuggled in a printing press, piece by piece so that local Jews could print and study the Torah in the officially atheist Soviet state.

Some others interviewed, such as Rene Borchardt, came to Ireland via Britain. She arrived in Dublin from Glasgow in 1947 and contrary, perhaps, to our expectations of a poverty stricken Ireland of that era, found it a place of abundance compared to Britain, where wartime rationing still applied. In Ireland she found ‘an overabundance of everything’, including such delicacies as cream and salmon.

From inner city to suburbs

Initially the Jewish community in Dublin, the largest on the island, was concentrated in the Portobello area, particularly along the South Circular Road, which housed numerous places of worship and Clanbrassil Street, where many Jewish owned businesses were located. Bertha Cohen, for example recalled that both sides of the street were filled with Jewish businesses included her uncle’s Kosher delicatessen.

The area has since been referred to as ‘Little Jerusalem’ though this appears to be retrospective, as few people, if anyone, called it that at the time. The area moreover, was never in any way monolithic in terms of ethnicity or religion, also housing both Catholic and Protestant schools and places of worship.

By the time of the youth of the ‘elders’ of the Statford College project, however, the Dublin Jewish community was beginning to suburbanise out its south inner-city enclave. Many moved out to the Terenure and Rathfarnham areas, then at the edge of the city. Rathfarnham, now a heavily populated sea of suburban housing, was, Heather Abrahamson recalled ‘then a place of tillage’.

The main Synagogue in Dublin at Terenure, which was founded in 1953 by Rabbi Jacobovtich and Statford College itself (founded in the following year in neighbouring Rathgar) both date from this post-war migration to the suburbs. At the same time, the South Circular Road area gradually lost its Jewish character. For instance, the synagogue at 32 Lennox Street, opened in 1887, closed in 1974. Another former synagogue at nearby Walworth Road houses the Irish Jewish Museum.

In the 1950s, there was a thriving and youthful Jewish community. Andrew Wolfe for instance remembered the Maccabi youth club as a ‘magical place’, where up to 900 teenagers would play sports like cricket, soccer and rugby. Len Kronn, 101 years old at the time of his interview, ‘remembered the dancing’ in social events of those years.

At that time also Ireland, particularly it seems, Northern Ireland, received its share of refugees from the Holocaust. Belfast, Lurgan and Cookstown, among others hosted young people from Austria, Germany and Czechoslovakia, part of the exhibition in Stratford College showed. Many of them were members of a Zionist youth group and perhaps ended up after 1948 in the new state of Israel.

Zionism, or support for a Jewish national state, may once have been a feature of the politics of the Irish Jewish community. Dublin produced one future President of the state of Israel Chaim Herzog, after whom the park adjacent to Stratford College is named. Attitudes today appear more ambivalent, however. Renee Borchardt for example recalled that though she was a strong Zionist in her youth, now ‘I don’t think it is a good idea to be a nationalist of any country’.

Nostalgia and changing times

If the predominant air of the project was one of nostalgia and celebration, there was also a certain element of melancholy. Though the Jewish community in Ireland has grown modestly in recent years, from just under 2,000 in 2011 to over 2,500 today, most of this is due to immigration of people from the United States, Israel and elsewhere to work in the multinational companies that have located in Ireland. Eddie Marcus thought that the old community ‘the Irish Jews’ have ‘almost disappeared’ due to age and migration.

Religious practices are also changing, as much among the Jewish community an any other in Ireland. Eddie Marcus noted that the new arrivals tend not to be very religious and in the week of writing, there is news that Dublin’s main synagogue at Terenure, home to a shrinking Orthodox Jewish congregation, is to be sold off and the place of worship moved to a smaller location nearby.

However, amid change and evolution, Statford College itself is thriving, having embraced students of all faiths and genders, whose Transition Year students contributed to a fascinating glimpse at both Jewish, Irish and Irish-Jewish social history.