Today in Irish History, 10 April 1923, Liam Lynch is killed.

The death of Liam Lynch signalled the effective end of the Irish Civil War. By John Dorney

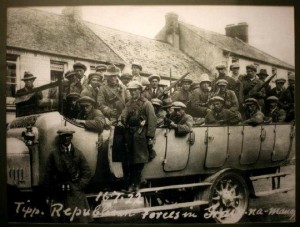

A small group of trench-coated men, senior anti-Treaty IRA officers, struggled hastily up the heather covered hillside. Behind them, in chase, were green uniformed National Army soldiers, calling on the men to halt and firing shots after them.

Frank Aiken was one of the six senior IRA officers, members of the Army Executive that commanded the guerrilla organisation. They had been billeted in a cottage in the Knockmealdown Mountains when they were told that ‘the Staters are crossing the mountains.’

It was, Aiken wrote ‘a much bigger round up than expected’ he put the Free State forces’ strength at up to 6,000 men. Fleeing over the hillside, his party got into a firefight with a column of 20 soldiers.

Liam Lynch’s death was not just another Civil War fatality, but marked the effective end of the war.

The guerrilla leaders were armed only with handguns, no match for the soldiers’ rifles and machine guns and had to make a run for it. They were escaping over the crest of the hill, Frank Aiken recalled, when, ‘a single shot rang out and Liam fell’. They started to carry him, but Lynch, in agony, ‘begged us to leave him’. He was picked up, badly wounded, by the National Army troops, who tried to treat him a in a local public house, in the small village of Newcastle, County Tipperary but Lynch died in hospital in Clonmel that night.[1]

Looked at one way, this was just another death in the Civil War that had dragged on since the previous June between pro and anti-Treaty Irish factions. The day before four men (two on either side) had died in an attack on a barracks at Oughterard County Galway. The day after, six Anti-Treaty Republican guerrillas were executed at Tuam and in County Waterford, an IRA column was rounded up and its leader killed.[2]

But Lynch’s death was not just another death. He was the Chief of Staff of the anti-Treaty IRA, its commander in chief and his death signalled the effective end of the Civil War. Just three weeks later, Frank Aiken, Lynch’s successor called a ceasefire. A month later he ordered IRA Volunteers to ‘dump arms’, ending the war.

Who was Liam Lynch, the man whose fate was inextricably tied with the course of the Irish Civil War?

No other law

Liam Lynch was just 29 years of age at the time of his death in 1923. Back in 1916 he had been working as a hardware clerk in Midleton, County Cork when he saw local Republicans the Kent brothers, the only Volunteers in that County to fire shots at Crown forces during the Easter Rising, being dragged away by the RIC.

According to his grandmother, he was still a Redmondite in 1916, ‘until the day the British attacked the Kents of Bawnyard and he saw Thomas Kent being brought in bleeding through the town of Fermoy, his poor mother dragging along after them’. Kent was later executed. [3]

Lynch famously declared in 1919, ‘We have declared for an Irish Republic, and will not live under any other law’.

Shortly thereafter Lynch joined the Volunteers, later to be renamed the IRA. By 1919 he was one of the new generation of firebrand Volunteer leaders. He summed up the attitude of his generation of Republican militants: ‘We have declared for an Irish Republic, and will not live under any other law’.[4]

In 1919 in Fermoy, Lynch led a raiding party that disarmed a party of British soldiers, shooting four, killing one and causing the enraged soldiers in response to shoot up the small town and burn down several local buildings. In 1920 he and Ernie O’Malley commanded an IRA force that attacked and took the police barracks at Mallow. By April 1921, Lynch had risen to become the commander of the IRA’s First Southern Division – a formation that encompassed many of the IRA’s most active units in Cork, Kerry and Limerick.

He was a man capable of fierce ruthlessness once his blood was up. When the British began executions of captured IRA men in 1921, Lynch wrote to IRA Chief of Staff Richard Mulcahy arguing that for every IRA prisoner the British executed, the Republicans should shoot a local loyalist civilian or a British prisoner: ‘If the enemy continue shooting our prisoners, then we should shoot theirs all round and they should be told so.’[5]

Lynch the fanatic?

For this and for his subsequent actions in the Civil War, Lynch has sometime been painted as a cold-eyed fanatic. The evidence however does not quite bear this out.

Lynch, far from being the cause of Civil War, was actually considered a moderate for several months after the Republican movement split over the Anglo-Irish Treaty.

He was, in fact, surprisingly equivocal when he first heard of the Treaty’s terms. He assured his brother Tom, that, although he would always ‘fight on for the recognition of the Republic’, the settlement was not without its good points. ‘There is no allegiance asked to the British Empire only to be faithful to it. At all times of course we give allegiance to the Irish constitution. You must realise the humiliating position of Great Britain to accept us on equal terms when she has no more authority than us or the states of the so-called Commonwealth’.

Lynch was not the most extreme IRA leader opposed to the Anglo-Irish Treaty and seems to have been swayed by his comrades into a more intransigent position.

He was confident that, although people might differ over the Treaty, ‘there will be no disunity as in the past’. And, although he had to agree to differ with Michael Collins, ‘it does not make us worse friends’.[6]

What apparently changed his mind was consulting with his own IRA officers in Cork, most of whom were against the Treaty.

On January 11, 1922 he signed a letter from IRA officers to Richard Mulcahy rejecting the Dail’s decision to approve the Treaty. ‘What’ he asked Mulcahy in a hand written note, ‘am I to do with thousands of men who sacrificed everything during the war?’

The anti-Treaty officers ‘contended that the Dáil support of the Treaty subverted the Republic and relieved the Army of its allegiance to the Dáil.’ [7] It would be ‘too degrading and dishonourable’, Lynch wrote in April, after the loss of hundreds of his comrades’ lives in 1919–21, ‘for the Irish people to accept the Treaty and enter the British Empire even if it were only for a short period’.[8]

What such intransigence on his part achieved, of course, was not a Republican victory, but simply more bloodshed. Nevertheless, Lynch, elected Chief of Staff of the new anti-Treaty IRA Executive in March 1922 was against launching hostilities against either the British or the new pro-Treaty or ‘Free State’ authorities. Indeed he vetoed the proposal of the militant IRA faction that had occupied the Four Courts in Dublin to do so.

Instead Lynch entered into months of tortuous negotiation with Michael Collins and Richard Mulcahy in an attempt to re-unite the IRA.

Civil War

For Lynch it was the pro-Treatyites, who opened fire on the anti-Treaty garrison in the Four Courts, on June 28, 1922, who bore the responsibility for the Civil War.

However obtuse it seemed to his former comrades Collins and Mulcahy, who saw in the anti-Treatyites’ stance the defiance of the nascent Irish democracy, Lynch saw the Civil War as a defensive reaction on the part of the anti-Treaty Republicans.

He was actually arrested in Dublin by pro-Treaty forces at the start of the fighting, but let go in the mistaken belief that he would be a moderating force in the anti-Treaty IRA. This proved to be a fatal error on the part of the pro-Treatyites, for Lynch would now become their implacable opponent.

He wrote to Ernie O’Malley on 25 July: ‘Since the attack on GHQ Four Courts and the splendid rush to arms of [the] IRA in defence of the Republic against domestic enemies we are finished with a policy of compromise and negotiation unless based on recognition of the Republic. This policy is and will be carried through by all officers and men … we have no intention of setting up a government but await such time as An Dáil will carry on as Government of the Republic … In the meantime, no other Government will be allowed to function.’[9]

Lynch viewed the outbreak of Civil War, with the government attack on the Four Courts, as a betrayal and depicted the subsequent anti-Treaty campaign as a defensive reaction.

Lynch and his colleagues then, would always argue that they were not ‘defying the will of the people’ as the pro-Treatyites argued, but rather defending the Republic against an unprovoked attack on them on British orders.

In the subsequent fighting Lynch briefly played the role of a conventional general; for about a month, controlling a headquarters in Cork and a substantial part of southern Munster. But the ‘Munster Republic’ crumbled under the assault of the pro-Treaty government forces in July and August 1922. Subsequently Lynch fell back on guerrilla tactics, in the hope that attrition and exhaustion would force the collapse of the Provisional Irish government and the re-negotiation of the Treaty.

The conflict grew more bitter and vindictive as it went on. At first Lynch forbade attacks on off-duty Free State forces, mistreatment of prisoners or the killing of informers. But when, in November 1922, the Free State authorities began executing captured anti-Treaty fighters, Lynch responded with a venomous widening of the Republican guerrillas’ pool of legitimate targets.

First he ordered the killing of Free State TDs who had voted for the ‘Murder Bill’, as well as members of the ‘Free State murder gang’ and ex British officers who had joined the National Army.[10]

When his orders were acted on and TD Sean Hales was assassinated in Dublin, the Free State retaliated with the summary execution of four imprisoned Republican leaders held in Mountjoy Gaol. Lynch in response widened his orders further to include the destruction of the houses of all Free State supporters. In January 1923 he wrote that ‘all Free State supporters are traitors and deserve the latter’s stark fate, therefore their houses must be destroyed at once.’[11]

Ending the war?

To almost everyone, even anti-Treaty political leader Eamon de Valera, such ruthlessness appeared counter-productive, but Lynch was convinced that with enough persistence, the Free State would collapse and the Irish Republic, abandoned under the Treaty, as he saw it, could be reborn.

He wrote to de Valera when the latter protested at the house burning campaign, ‘The Free State is on the verge of collapse and the burnings are an important part. The IRA wishes to fight with clean hands but the enemy has outraged all the rules of warfare. We must adopt severe measures or chuck it in [i.e. give up] at once.’[12]

By the spring of 1923, however, with the anti-Treaty IRA reduced by mass arrests and imprisonment to small scale acts of sabotage, many on his own side were pressing Liam Lynch to bring the bloodshed to and end and call a ceasefire. De Valera wrote to Lynch that ‘we need to take the lead on peace, it would be a victory.’[13]

But in an IRA Executive meeting in the Knockmealdown Mountains in March 26, 1923, Lynch narrowly carried the vote to continue the war.

Papers Lynch was carrying at the time of his death appear to show that he was about to end the war when he was killed.

For this, again, history has not been kind to Liam Lynch. Some have even likened his behaviour to that of Hitler in the Berlin bunker in 1945, moving imaginary columns of troops around a map even as Soviet troops advanced in the streets above.

But Lynch’s surviving papers tell another story. It seems that, at the time of his death, Lynch was finally preparing to acknowledge reality. In a tiny, scuffed notebook, held today in the Military Archives in Cathal Brugha Barracks in Dublin, that was captured on Lynch by National Army troops, he had written notes for the forthcoming Executive meeting. They note, the ‘futility of military effort’ and called for a ‘free choice of the people before the Volunteers hand in their arms.’ Also scribbled in small hand writing is a call for ‘an immediate cessation of hostilities.’[14]

Lynch, in other words, seems to have been about to call off the anti-Treaty IRA campaign at the time of his death. However, he never got the chance.

Death

It appears that information about Lynch’s whereabouts was extracted from high ranking anti-Treaty prisoners in Dublin.

According to National Army Quartermaster General Seán McMahon, ‘it was the result of good intelligence work in Dublin … a small piece of information picked up in a raid in Dublin, pieced together scraps of information that something important was happening in the south … GHQ ordered a large operation that resulted in the capture of the Irregular leaders and the ultimate collapse of Irregular opposition’.[15]

That day on the mountain top when Lynch was shot, Frank Aiken recalled that he ‘begged us to leave him’. They said an Act of Contrition, took his gun and his pocket book and made their escape across the mountain with rifle and machine gun bullets whizzing past them. ‘It was the hardest thing, Aiken wrote ‘that any of us ever had to do’. ‘None of us could understand why out of six of us, he was hit or why we were not all killed, it was just God’s will’.[16]

Lynch shared his dying thoughts with a National Army officer who had also been an IRA Volunteer in the war against the British, who reported Lynch as saying, ‘it [the Civil War] should never have happened. I am glad now to be going away from it. Poor Ireland, poor Ireland!’[17]

Among Lynch’s last words were, ‘It should never have happened’.

Like most historical figures, when looked at closely enough, Liam Lynch comes out as much more complicated than the simple image of the fanatical Republican militarist. He viewed the Civil War, justly or unjustly, as a defensive reaction and never, contrary to the charges leveled against him, proposed installing an IRA military dictatorship.

And yet he, as much as anyone, bears responsibility for the needless dragging out of the Civil War and for its descent into such a bitter and ugly vendetta.

References

[1] Florence O’Donoghue Papers, NLI MS 31,242

[2] See a chronology here https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Timeline_of_the_Irish_Civil_War#April_1923

[3] Hart, The IRA and its Enemies, p.205; McGarry, The Rising, p.281

[4] Ryan, Meda, Liam Lynch, the Real Chief, p.13

[5] Maryann Gialanella Valiulis, Richard Mulcahy: Portrait of a Revolutionary (Dublin: Irish Academic Press, 1992), pp. 69–70.

[6] Liam Lynch to Tom Lynch, 12 December 1921, in O’Malley and Anne Dolan, No Surrender Here!, p. 12.

[7] Mulcahy statement on Army situation, 4 May 1922 MP/7/B/192

[8] Lynch to Mrs Cleary, 10 April 1922, Florence O’Donoghue Papers, NLI, ms 31,242

[9] Lynch to O’Malley, 25/7/22, in O’Malley and Dolan, No Surrender Here!, p. 68.

[10] Operations Order Number 30, November 1922, contained in O’Malley and Dolan, No Surrender Here!, p. 529.

[11] Liam Lynch IRA General Orders 9/12/22 in Twomey Papers, UCD P67/2.

[12] De Valera Papers UCD P150/1749.

[13] De Valera to Lynch 7/2/1923 De Valera Papers UCD P150/1749.

[14] Captured documents on Liam Lynch IE/MA/CW/CAPT Lot 78.

[15] McMahon testimony, Army Inquiry 1924, Mulcahy Papers UCD P7/C/14.

[16] Florence O’Donoghue Papers, NLI MS 31,242

[17] Ryan, Liam Lynch, p165