The Burning of the Big Houses Revisited 1920-23

By John Dorney

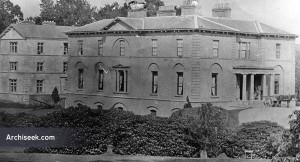

The very name ‘Big House’ has a certain resonance in Irish historical memory. The Big House was the citadel of the ‘landlord’, of the ‘Anglo-Irish’ of the ‘Protestant Ascendancy’ that had formed the backbone of British colonial rule.

Thus the spectacle of 275 of the ‘Big Houses’ going up in flames remains one of the most potent images of the Irish Revolution of 1916-23. It was a sign after all that the past really was finished and that a new order was being born.

In 2011, I wrote an article here on The Irish Story titled ‘The Big House and the Irish Revolution’ on the destruction of the country mansions during the Irish independence struggle, 1919-23. I made the point that the Big Houses were specially targeted in the Civil war of 1922-23 and argued that it was done basically as a symbol by the anti-Treatyites to show that the revolution was not over with the Treaty and that there would be no compromise with, as they saw it ‘Imperialist’ elements in the new Ireland.

This article will reconsider the reasons for the burning and destruction of the Mansions of the old landed class in 1920-23.

The article has generated a lot of interest in the intervening years, but further research has led me to wish to revise it somewhat.

The key points I wish to address are these; Was the old landlord class really finished as economic power by 1920 (as a result of the 1909 Land Act) as I argued in 2011? Did the burnings represent agrarian class war as well as a nationalist political conflict? Thirdly, how do we explain the burnings in the Civil War especially, do the burnings of the Big Houses represent part of anti-Protestant or sectarian campaign on behalf of republicans?

To go some way to answering these questions I will look at two specific areas of which I have knowledge; the area around County Dublin in which the IRA Dublin Brigades operated and the border region from Dundalk to Leitrim.

Was the Land Question settled?

So first, were the Big Houses still bastions of ‘landlordism’ – where absentee landowners of Anglo-Irish, colonial origin ‘rack-rented’ their tenants?

It is a truism of Irish history to say that the land question had been settled by the 1903 and 1909 Land Acts, which enabled tenant farmers to buy out their landlords with long term loans from the British government. And to a large degree this is true.

However what had essentially happened was that bigger tenants had bought out their farms, and in many cases consolidated them into ‘ranches’ where they could raise cattle for export. Smaller tenants, or those whose landlords simply did not want to sell often still paid rent to traditional landlords.

Certainly this was true in the border region. At an ‘unpurchased tenants’ conference in April 1922, over 1,000 delegates resolved that: ‘the [new] Irish government must complete compulsory land purchase’. They heard that there were over 100,000 ‘unpurchased tenants’ in the 26 counties [Irish Free State] and 2,500 in County Cavan alone. The Cavan delegate Coffey declared, ‘We have been wronged and robbed by landlords.’[1]

A look at the border counties shows that the issue of tenant vs landlord conflict was far from over in 1921.

Far from conflict between tenants and landlords being a thing of the past, in the border region at least it intensified in late 1921 and early 1922 as the British government began to withdraw from southern Ireland and the new Free State authorities made halting steps to replace them.

In November 1921 a rent strike started on the Portland Estate, County Monaghan, owned by Captain Maxwell, and operated by his agent agent McNorris Croddard.

The tenants demanded that due to a slump in agricultural prices due to a worldwide recession, they could not afford to pay the rent. They agreed to withhold rent altogether unless it was cut by 85% or the landlord sold up altogether. They were shortly afterwards joined by tenants at Baileboro, Cavan on the Lancaster Kellet estate who said they would take ‘defensive action, if forced to pay rent.[2]

There followed similar rent strikes all across the region – on 3 more landed estates by December; Bawnboy Cavan, Logan Ellis Estate the Montgomery Estate and the Rothwell Estate, owned by Major Purdon).[3]

These were the classic tactics of the ‘Land wars’ of the late 19th century. But with the added factor of calling on the new Irish government to compulsorily purchase the land.

At the Coolamber estate in Longford for example, Tenants asserted they had tried to buy their plots off the Stanley family since 1908, without success. But, ‘times and conditions have altered in Ireland’.’ We cannot raise our offer without bringing obloquy for ourselves and being unjust to other tenants. We do not consider that you have made any sincere effort to give us the benefits of the Land Acts. We are the only tenants in Longford still paying rent to a landlord’. No rent would be paid, they declared until purchase was agreed.[4]

Placating this, mostly peaceful revolt by tenant farmers occupied a large amount of time, (borrowed) money and effort on behalf of the Free State authorities even during the Civil War and led to the land act of 1923.

In short, in poor rural regions big landlords still existed. They were indeed often absentees, represented by agents and many of them if not ‘Cromwellians’ as nationalists often alleged, had ties with the British military and political establishment.

Around Dublin in the more prosperous counties of Meath and Kildare and the mountainous and sparsely populated county Wicklow, there is another picture however. Here, there were many ‘big houses’, many of which, as we will see, were targeted in the Civil War, and many of them were owned by former and in some cases practicing unionists

However either because land purchase had gone further in this, more prosperous region, or because excess labour migrated to the city, there was little in the way of tenant farmer-against landlord conflict. This is not to say there was not rural class conflict – there was, and in the years of nationalist revolution it was sometimes violent, but it consisted mainly of strikes by agricultural labourers against their farmer employers.

There was a mass rent strike among tenant farmers across Cavan, Monaghan, and Longford in late 1921 and early 1922

Another salient factor is that many of the ‘Big Houses’ around Dublin, though owned by unionists, were not owned by landlords in the classical sense. Baron Glenavy, or James Campbell, for instance, elected as a Unionist MP for Dublin in 1898, a close associate of Edward Carson in his campaign against Home Rule, a Chief Justice for Ireland in 1916 and chairman of the first Free State Senate, did not come from a land-owning background but had made a successful career in law. He was ennobled only in 1921. That his home in Kimmage, south Dublin was burned in the Civil War was entirely due to political not economic antipathy.[5]

The Guinness family similarly were industrialists, makers of the famous beer in Dublin city, but owned sprawling country houses outside the city in south Dublin and Wicklow. They had been noted if not, like Glenavy, as militant unionists, certainly as ‘Empire loyalists’ – urging their workforce for instance to join the British armed forces during the Great War. Their property too was targeted in 1923 by republicans.

In short, when we speak of the ‘Anglo-Irish’ or the ‘landed class’ at the time of the Irish revolution we are speaking of a very varied group. In some places they were still prominent landlords, in others they were the sons of professionals and industrialists who had simply adopted some of the lifestyle of the older landed gentry.

Were the Big House burnings a form of class conflict?

We have seen that in some areas big landed estates still existed and that there was mass and organised opposition to them among tenants.

So it is tempting to think that in areas like the border region at least, the Big House burnings were the result of local tensions, part of the concerted campaign by tenants’ organizations to force their landlords to either slash rent or sell up.

Most of the Big House burnings in this area occurred in the spring and summer of 1921, during the most bitter months of the War of Independence between IRA guerrillas and British forces.

The first to be destroyed in March 1921 was Gola House, County Monaghan, the property of William Black, resident in South Africa. According to the local newspaper it was burnt because British Army planned to use it for a garrison.[6]

There followed in June 1921 a spate of spate of Big House burnings in the region. On June 4, Lanesboro House, Cavan, the property of the Earl of Lanesboro was burnt and nearby Tomkinroad House, Belturbet was blown up with explosives.[7] On June 18th Ravensdale Castle, seat of the Earl of Arran, between Dundalk and Newry in County Louth was burned along with the courthouse in the town of Ravensdale. The Earl of Arran had recently sold the house to a timber firm and being unoccupied it would also have been a prime site for a military garrison. In Cavan, Stradone House was burnt shortly afterwards on June 29, 1921. [8]

The Big House burnings in the border region seem to have been motivated by the guerrilla priorities of the IRA rather than agrarian reasons.

On July 8, Shanton House, Ballybay, Monaghan, the property of the landlord Fitzherbert was destroyed. Fitzherbert himself attended once a year to collect rent, but lived in Queenstown (now Cobh, County Cork). His caretaker was held up, and his house burned. Crown forces were reported to be guarding other Big Houses in the area.[9]

This was months before the land agitation took off in the border region and it took place at a time when the agricultural recession had still not hit farmers. On the other hand it also occurred at a time when Crown forces, both police and military, were re-doubling their efforts in the region to stamp out IRA guerrillas.

Between the 30th of May and the 16th of June 1921, a cavalry column consisting of three regiments, the Carbiniers, the 10th Royal Hussar and the 12th Royal Lancers, supported by the Royal Irish Constabulary and Auxiliaries as well as by military aeroplanes, mounted a ‘drive’ through counties Longford Leitrim, Cavan and Monaghan. They recorded arresting 600 men in Longford, 700 in Leitrim and about 900 in Monaghan, of whom about 120 were sent to the internment camp at Ballykinlar.[10]

The burnings in the north midlands coincided with a British military sweep through the area.

Though the very lightly armed guerrillas in the region could do very little against such large and well equipped forces (only one soldier of the three cavalry regiments was wounded in the operation, during a gun attack in Longford), they were determined to deny them garrisons. It very much looks as if the operations to destroy Big Houses in June and July 1921 in the border region at least were done to deny them to the British Army rather than for agrarian motives.

There were no further Big House burnings in the region until well into the Civil War, when, as we will see they became IRA policy. This is despite the fact that it was precisely in the Truce period from July 1921 to June 1922 that the rent strike and other agrarian agitation was at its height in the border counties.

There was plenty of class conflict in all its forms, including violence and house burnings, but the Big Houses were not the main target. It seems therefore, that in this region at least it was the guerrilla tactics of the IRA and not agrarian motives that were main motive for targeting the Big Houses.

This backs up James Donnelly’s argument relating to County Cork ,where by his count over 50 Big Houses were destroyed during the ‘Tan War’, that although there may have been agrarian or sectarian animosities at work, most Big House burnings were carried out by the IRA either to deny them as billets to the British forces or as reprisals for the British house-burning policy.[11]

Explaining the Civil War Burnings

As I wrote in my 2011 article, the majority of ‘Big House burnings’ took place during the Civil War of 1922-23 – 199 Mansions destroyed against 76 in the ‘Tan War’. [12] How do we explain this?

In my previous article I argued that it was because anti-Treaty IRA guerrillas could do little else by late 1922 having been reduced to small bands and fearful of falling victim to the Free State’s increasing use of execution if they were captured. Out of military impotence they resorted to destroying the symbols of the old British order in Ireland.

None of this is wrong, but one point that is important to make is that the burnings of the Big Houses were not a spontaneous action by anti-Treaty IRA units on the ground but were explicitly ordered by IRA GHQ and in particular by their Chief of Staff Liam Lynch in reprisal for the Free State execution policy that began in November 1922.

In Dublin the Civil War house burning campaign was a specific response to the Free State execution policy.

There had been isolated attacks on former unionists in the Dublin area before this point, particularly by the Second Dublin Brigade, which operated in the south of the County. For instance in August 1922 they raided the house of Henry Robinson (a prominent ex unionist) and after a gun fight he surrendered 3 pistols and 30s rounds. Later that month the same Brigade burned ‘Errigal Mansion’ to prevent it being used by Civic Guards (police) as a barracks. [13] But this was nothing on the scale of what was to come.

In reprisal for Free State executions of 8 anti-Treaty guerrillas in November 1922, IRA gunmen shot two members of the Dail, killing one, Sean Hales. In retaliation on December 8th, the government shot four leading republicans who been prisoners since July 1922 – Liam Mellow, Richard Barrett, Rory O’Connor and Joe McKelvey.

Liam Lynch the following day issued a General order that, ‘all Free State supporters are traitors and deserve the latter’s stark fate, therefore their houses must be destroyed at once.’[14] In Dublin the concerted attacks on civilian Free State supporters by the anti-Treaty fighters can be dated quite precisely from this point onwards.

Between December 10, 1922 and the end of April 1923 the IRA Dublin Brigades deliberately destroyed either through burning – usually with petrol – or explosives, 28 civilian homes along with 6 income tax offices, a number of hotels and attempted to destroy several cinemas and theatres as well.[15] Of these homes, 9 could be counted as Big Houses or mansions associated with the Anglo-Irish class.

Nine out of 28 houses destroyed by the anti-Treaty IRA Dublin Brigades could be counted as Big Houses.

The first was the house of Gordon Campbell, Lord Glenavy in Kimmage south Dublin, which was burnt on December 18th. Glenavy was Chairman of the Free State Senate.

On January 29th, a night that saw four houses destroyed by the IRA in Dublin, one, the house of Dennison on Lansdowne Road which was blown up and ‘completely destroyed’ could be counted as Big House (albeit urban in this case).

On the 16th of February, the IRA Second Dublin Brigade burned the house of Sir Brian Mahon at Ballymore Eustace, a senator and enclosed further reports of having destroyed; Lord Mayo’s Palmerstown House in Kildare, Horace Plunkett (the co-operative activist)’s house at Foxrock, Kippure Lodge in County Wicklow and 3 houses of informers around Blessington. [16]

On 27 February an attempt was made to blow up Dartry House home of Dr Lombard Murphy. The bomb did not go off.[17] A month later, Republicans attempted to burn and lay a land mine in Burton Hall, Sandyford, the home of the Guinness family, one of whom was a senator. The fire failed to ignite and the mine was defused by Free State troops.[18]

Finally a month after that on April 21st the IRA Dublin 6th Battalion (North County Dublin) reported burning the house of the ‘Imperialist Wilkinson’, and the house of Major Bomford, a ‘Big unionist’ at Ferns Lock Co Meath. [19]

In the border counties too, the burnings of the Big Houses seem to have been specific response to the executions of Republicans. Three Republicans were executed in Dundalk on January 13th 1923 and another three on January 22nd.[20]

In reprisal for that and in accordance with IRA GHQ orders, a number of Big Houses in the area were destroyed.

On February 3, 1923 Milltown Castle, at Castlebellingham, County Louth was burned, followed by Annaskeagh House, near Dundalk ,burned and blown up – residence of AN Sheridan, a Judge and a month later Clonyn Castle at Delvin County Westmeath.[21]

‘Imperialists and Freemasons’

This all represent a significant degree of violence against civilians. Moreover there was an element of prejudice at work in the IRA against people they termed ‘Imperialist’.

The Senate, which initially was intended to represent former unionists from the Anglo-Irish and more generally Protestant communities, was a particular victim. On 26 January 1923, the anti-Treaty IRA Adjutant General (Con Moloney) issued the following order.

- Houses of members of ‘Free State Senate’ in attached list marked A and B will be destroyed.

- From the above date if any of our Prisoners of War are executed by the enemy one the Senators in the attached list…will be shot in reprisal.[22]

Moloney attached a list of the names of 20 Senators and their addresses. Of these, 14 on list A were liable for possible assassination.

Republican prejudice against ‘Imperialists and Freemasons’ played a part in the campaign but violence against ex unionists

In fact none of them were killed. However those marked for death included ‘John Bagwell, General Manager Great Northern Railway, Imperialist and Freemason’ , Henry Wilson, ‘heir to the Marquis of Lansdowne, Imperialist and Freemason’, Andrew Jameson, Chairman of Bank of Ireland and Bryan Mahon Commander in Chief of British force in Ireland 1916-18 ‘Imperialist and Freemason’. Campbell or Glenavy the Chairman was not marked for assassination, though his home was marked for destruction. [23]

Terms like ‘Imperialist and Freemason’ could easily be taken as code words for ‘upper class Protestants’. Liam Lynch the IRA Chief of Staff also contemplated at one stage even more radical action, writing to the anti-Treaty Republicans’ ‘President’ Eamon de Valera in January 1923 advocating ‘shooting a large number of Senators’ – ‘at least 4’ – in reprisal for each execution. He voiced the opinion that shooting prominent loyalists or taking them hostage had ‘had most satisfactory results in the last war [against the British] in 1921’. Attacks on the ‘enemy civilian garrison’ [loyalists], he wrote, ‘did more to bring about the Truce [against the British] than anything else’.

De Valera for his part was generally a retraining influence on Lynch telling him, ‘it is unjustifiable to take the life of an innocent man and to make him suffer for the acts of the guilty’. They should not, he argued, target ex unionists who ‘are far less to blame than some Republicans who went Free State’.[24]

The majority of those targeted in the house burning campaign by the anti-Treaty IRA were nationalist supporters of the Free State.

However, it is important to remember that, even taking house burning alone as a category of anti-Treaty attacks in the Civil War, the considerable majority of houses destroyed were not ‘Big’ but small houses –the homes of Catholic, usually nationalist Free State supporters.

Of the Dublin attacks listed above 19 out of 28 houses attacked could not be considered Big Houses. Republicans were especially vindictive in targeting other Republicans who had taken the Free State side, Dennis McCullough, for instance (a onetime President of the Irish Republican Brotherhood) saw his shop on Dawson Street blown up, as was the house Jenny Wyse Power, the prominent Cumann na mBan activist who had split off to found the pro-Treaty group Cumann na Saoirse.

Sean McGarry another pro-Treaty IRB man had his house in Fairview burned down with his seven year old son Emmet still inside. He died in the fire. Apart from Emmet McGarry the only other fatal victim of the burning campaign in Dublin was Peter Carney, who was fatally injured when the IRA burned the income tax office where he worked in February 1923. [25]

Dartry House, listed above as one of the Big Houses attacked, was targeted for its owner the (Catholic) Murphy family’s association with the Irish Independent newspaper, hated by Republicans for its fierce hostility to them in the Civil War. The anti-Treaty IRA also attempted to burn down the Independent’s editor ’s house (‘for the doing in of one of our men, Toohey’ they told him) and attacked its office multiple times.[26]

Similarly, in the border counties, it is wrong to suggest that the Big Houses and their owners took the brunt of Republican reprisals for the government’s execution policy. There was for instance an attempt to burn the offices of the Dundalk Democrat newspaper for its pro-Treaty stance, as well as the houses Cavan TD William Cole and Monaghan Senator O’Rourke. There were also at least two civilians shot and killed in January 1923 as alleged informers in the Dundalk area. [27]

Conclusions

In conclusion then the burning of the Big Houses was and remains one of the most visually arresting images of the Irish revolutionary era.

It is incorrect to imagine that the old Anglo-Irish landed class was already a thing of the past by the 1920s. Rather its status differed very much depending on local circumstances and in any case the owners of the ‘Big Houses’ were a very varied group by this time – including as well as the classic absentee landlords, professional and industrial families.

Their politics should also not be assumed, some were indeed hardline unionists, but some such as Horace Plunket and Maurice Moore in Mayo were liberals and nationalists of a sort.

Regarding the burnings, though there were still very significant agrarian tensions in some parts of Ireland including rent strikes aimed at the landlords, they do not appear to have played a very big part in the Big House burning campaigns. These peaked in the summer of 1921, at the height of the War of Independence and again in early 1923 at a time when the Civil war was descending into a spiral of reprisals. It was the orders of the IRA GHQ in 1921 and the anti-Treaty IRA GHQ the following year that were mainly responsible for burning policy, rather than local prejudice.

Finally while IRA prejudices against ‘Imperialists and Freemasons’ certainly played a part in the selection of targets for burning, neither this nor other forms of violence against civilians in the Civil War were predominantly directed against either the Anglo-Irish upper class or Protestants in general.

References

[1] Anglo Celt May 6, 1922

[2] Anglo Celt November 25 1921

[3] Anglo Celt December 24 1921

[4] Anglo-Celt December 31, 1921

[5] William Delaney The Green and the Red revolutionary Republicanism and Socialism in Irish History, p144

[6] Anglo Celt March 5, 1921

[7] Anglo Celt June 4 1921

[8] For Ravensdale, Irish Times June 20, 1921, this website on Shanton House

[9] Anglo Celt July 7 1921

[10] William Sheehan, Hearts and Mines, The British 5th division in Ireland, 1920-22, p228-234.

[11] James S Donnelly Bi House Burnings in County Cork during the Irish revolution, 1920-21, in Eire/Ireland 47 Fall/Winter 2012. Online here. http://www.nuigalway.ie/research/centre_irish_studies/documents/0647.34donnelly.pdf

[12] Peter Martin, Unionism: The Irish Nobility and the Revolution 1919-23 in The Irish Revolution, Joost Augustein (ed), Palgrave 2002. P157

[13] Military Archives Cathal Brugha Barracks, Capt Docs IE/MA/Capt/Lot28

[14] Liam Lynch IRA General Orders 9/12/22 in Twomey Papers, UCD P67/2

[15] Source: principally National Army Dublin command Operations reports, CW/OPS/07/01 and CW/OPS/07/02

[16] IRA Dub 2 Bde reports UCD Twomey p69/22

[17] NA Dublin reports CW/OPS/07/02

[18] Ibid, CW/OPS/07/03

[19] Dublin 1 Bde reports Twomey Papers UCD p69/20

[20] Wolfe tone Annual 1966, p27-28

[21] Anglo Celt, February 3, 17 and March 17, 1923

[22] Cormac O’Malley, Anne Dolan (eds) No Surrender Here! The Civil War Papers of Ernie O’Malley, 533

[23] Ibid.

[24] De Valera Lynch Correspondence 15-16 January 1923 in de Valera Papers, UCD P150/1749

[25] National Army Dublin reports CW/OPS/07/01

[26] Ibid.

[27] Anglo Celt, January 6, 1923