Who was Seamus Dwyer?

Michael McKenna tells the forgotten story of the life and death of Seamus Dwyer, Sinn Fein and IRA activist and pro-Treaty politician, killed in December 1922 during the Irish Civil War. (Aka Seamus O’Dwyer, Séamus O Duibhir, James O’Dwyer, James Dwyer).

Was it worth it?

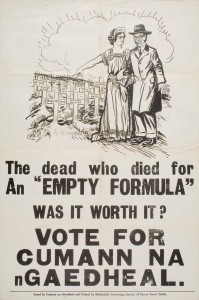

In 1932 a Cumann na nGaedhael election poster featured the figure of Erin wearing a tiara-style headpiece and a Celtic style dress with a broach similar to the Tara broach on her bodice, taking the arm of a reluctant de Valera, shown wearing a hat and a trench coat.

She is sternly pointing to a number of white crosses in a burial ground, those in the foreground are labelled with the names ‘Rory O’Connor’, ‘Michael Collins’, ‘Cathal Brugha’, ‘Seamus Dwyer’, ‘Sean Hales’, ‘Emmet McGarry’, ‘Liam Mellows’ and ‘Erskine Childers’. Underneath this image is written, ‘The dead who died for an ‘EMPTY FORMULA’. Was it worth it? Vote for Cumann na nGaedheal’.

It is a strange election message, a decade after the bloodshed of the Civil War the Cumann na nGaedheal government were using the names of the dead heroes from both sides in a vain attempt to prevent Fianna Fail under de Valera from gaining power. Rory O’Connor, Cathal Brugha, Liam Mellows and Erskine Childers are all well-known Republican figures killed or executed by the Free State during the Civil War.

Michael Collins and Sean Hales are equally well-known pro-Treaty figures killed by their Republican opponents, while Emmet McGarry was the five year old son of a Pro-Treaty politician, tragically killed in December 1922 when his home was firebombed by Republicans the night before the first sitting of the Provisional Government.

However, despite his relative prominence at the time, Seamus Dwyer is largely forgotten today.

Who Was Seamus Dwyer?

Seamus Dwyer was christened James and took the Irish form of his name in later life. He was the younger of twin boys; he and his elder brother, Luke, were born on the 15th November 1886. Their parents William Dwyer (b. 1853) and Margaret Walker (b. 1859) both hailed from Co. Wicklow. William Dwyer was the principal partner at the firm of Messrs. O’Neill & Dwyer, Provision Merchants, 4 Lower Baggot Street, a well-known grocer. They went on to have four more children, two boys and two girls.

Seamus Dwyer came from a well-off middle class Dublin family and went into business as a ‘high class grocer’ in the suburb of Rathmines.

All four boys were educated at Blackrock College over a fifteen year period between 1895 when James and Luke entered and 1910 when Edward graduated. Luke graduated from UCD with a BA in 1908. It is not recorded whether his brother James attended university, but as he followed his father ‘into trade’, probably not.

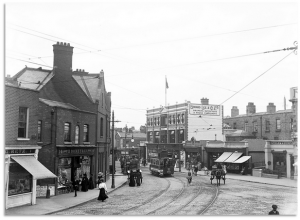

In or around 1908, at about the same time as his brother was graduating from UCD, Seamus Dwyer established a high class spirit grocery (off-licence/grocery shop) at 5 Rathmines Terrace in a busy area of Rathmines.

On the 6th October 1914, as his business became established, Dwyer married Marie, daughter of the late Matthew Molloy of Duke Street, in St. Michan’s Church. Dwyer and his new wife lived in an apartment above the store in Rathmines.

A ‘James O’Dwyer’ fought in City Hall with the Irish Citizen Army during the 1916 Rising, but it seems unlikely that a man of Dwyer’s background, fast becoming a prominent businessman, would have joined the ICA which was drawn from the Trades Unions and working class. Dwyer was a member of Rathmines Urban Council, a member of the Committee of Management of the New Ireland Assurance Society, which had offices in O’Connell Street over Kapp & Petersons, and Vice-President of the Family Grocers and Purveyor’s Association. He also liked a round of golf and joined the Robin Hood Golf Club (now Newlands Golf Club) which is located near Newlands Cross on the Naas Road.

Dwyer was also becoming increasingly active in Sinn Fein politics and was recognised as a very prominent member of Sinn Fein in the Rathmines and South Dublin areas. Cahir Davitt, a Judge in the Dáil Courts in 1921 and later the first Attorney General of the Free State, recalled sitting as a judge in the District Court in Rathmines around this time where the other two judges were Erskine Childers and James Dwyer.[1] Neither judge was to survive the Civil War.

Political Intelligence

Dwyer also become involved in the military struggle for Irish independence and served as the Intelligence Officer (I/O) for G Company, 4th Battalion, Dublin Brigade IRA during the War of Independence. He was arrested and imprisoned by the British for a time in 1920.[2]

Seamus Dwyer worked with Michael Collins on policy material, rather than military operations. He was a member of the Second Dáil, which sat on August 16, 1921. [3]

According to Dan Bryan, I/O for the 4th Battalion during the War of Independence and later the Irish Army’s Director of Intelligence, Dwyer’s main role was as a link between senior Dublin Castle official Sir James MacMahon and Michael Collins.

Dwyer worked closely with Michael Collins on intelligence matters and was a key link between him and high ranking officials in Dublin Castle in 1919-21.

Bryan described the new hard line Castle administration that arrived with Sir John Anderson as part of the reorganisation of the administration in Ireland in the spring of 1920 as being ‘associated with an effort by the military and extreme crowd in the Castle to secure a military victory’ but he also describes how Collins had been able to anticipate the changes in Dublin Castle based on information which Dwyer had been able to obtain at the Kildare Street Club and Bryan speculated ‘this may have led Collins to encourage him [Dwyer] in this line of activity’.

MacMahon, born in Belfast in 1885, was senior civil servant in the British administration in Ireland 1918, largely in an effort to placate Catholic opinion, he was appointed Under Secretary for Ireland by General John French, Lord-Lieutenant of Ireland. He was French’s contact with the Roman Catholic hierarchy and later with Collins himself. He was instrumental in negotiation which led to the truce of July 11, 1921 that ended the fighting in War of Independence.[4]

Bryan confirmed that, as I/O of C Company, Dwyer reported to him ‘on ordinary Volunteer intelligence’. However, through his business, family and school connections, Dwyer had social contacts which rank and file members of the Volunteers would not normally have had access to and Bryan stated that ‘…in addition, however, he had special sources of intelligence in wider fields, such as; the political, and in connection with those he dealt directly with Director of Intelligence – Michael Collins’.

Collins’ flair for secrecy is demonstrated by the fact that, while Bryan was Dwyer’s immediate superior in Intelligence, he was not aware of the particulars of Dwyer’s work with Collins. The only thing he could recall being shown was a report which Dwyer was preparing for Collins in the late Spring or early Summer of 1921 about discussions which he had had with MacMahon, whom Dwyer had met on at least two occasions.

…strangely enough, the only item in this report that I can now recollect was one on Sir Henry Robinson, the then British Chief of Local Government in Ireland, which was to the effect that McMahon(sic) regretted having to admit that Robinson, whom he previously regarded as a decent man, had now gone completely over to the side of the extreme military clique or crowd in the Castle.

While Bryan found it hard to remember the specifics of the report, he said that it ‘…generally dealt with information given by McMahon (sic) on the political condition of the British Government in Ireland and related subjects’.

Despite MacMahon’s surprising choices of personal secretaries (including Michael Collins’ and IRA Intelligence officer Joe McGrath’s cousins), his behind the scenes contacts with Nationalist leaders and his intelligence contacts with Dwyer, Bryan did not believe that the Dwyer-MacMahon relationship was an intelligence one or that MacMahon was being run as an agent by Dwyer.

Rather he felt that MacMahon would have known Dwyer as ‘as a sensible, shrewd man, who was very prominent in the Sinn Féin organisation and in the political activities of the period’ and he felt that ‘McMahon (sic) was merely anxious to discuss the general situation with a man who was both a member of Dáil Eireann and a driving force in the Sinn Féin and related organisations’. In fact he believed that, despite Dwyer’s earlier arrest and release in 1920, there would have been no way for MacMahon to know that Dwyer was involved in military activities at all.

Political Activities

Seamus Dwyer was elected unopposed as the Sinn Féin TD for Dublin County in the Second Dáil, which convened from 16 August 1921 until 8 June 1922. Dwyer had been one of the Cuala Group, a mixed coalition of Sinn Fein candidates in Rathmines, including figures as diverse as Dwyer, Thomas O’Connor, an accountant and company director, Dr. Kathleen Lynn and relatives of some of the 1916 martyrs, such as Áine Ceannt.

The group published the Cuala News under the banner ‘Ireland Over All’ and asserted ‘our right to speak our minds to our own people in our own country’. It launched a savage attack on Rathmines Urban District as Dublin’s ‘convalescent home and asylum of Freemasonary and Orangeism’. The group stressed Sinn Féin’s commitment to women’s rights but failed to mention any other social or economic issues.[5]

Seamus Dwyer was to the forefront of efforts to reunite the IRA after it split over the Treaty. He ran as a pro-Treaty candidate in the 1922 election but failed to be reelected

One of the most important acts of the Second Dáil was to bring an end to the War of Independence by ratifying the controversial Anglo-Irish Treaty which had been signed on 6th December 1921. Dwyer was a strong Pro-Treaty member and in the Treaty Debates Dwyer is recorded as supporting a motion put forward by Dr. V White of Waterford that the debates be held in private and Dwyer gave his reasoning as follows;

I think nobody in this Dáil has the slightest reason to fear publicity. There is this to be feared, that we here with this enormous responsibility cast upon us may be slightly over-awed in the first place by the presence of people who have not got the responsibility that we have. Number two, I feel that we are all young men and young women in this very important departure in our national affairs, and it is quite possible that with the best intentions in the world that we will say things which will bear a construction that we do not intend. For that reason more than for any other reason, not because I personally fear publicity, but to secure in the first place a full and free discussion and in the second place to secure that afterwards we will not be misunderstood, I support very strongly Dr. White’s motion.

The Collins-de Valera Pact

The Treaty debate was ‘a long drawn out, bitter and hostile affair’[6] which mostly revolved around the Oath of Allegiance, which neither side liked but which the pro-Treaty side argued was a necessary evil.

Eventually on 7th January 1922 the Dáil voted by 64 votes to 57 to accept it and de Valera led a walk out of his supporters from the house while the pro-Treaty faction formed a Provisional Government under Arthur Griffith.

De Valera led his supporters back into the Dáil as efforts for compromise between him and Collins continued. The two men decided to postpone elections until June and in May Seamus Dwyer was appointed as the Secretary of the Peace Committee of Ten which brought about the agreement between Collins and de Valera known as the Collins-de Valera Pact in a vain attempt to avert the looming conflict. James Dwyer actually drafted the agreement itself.

The IRA also split along pro- and anti-Treaty lines and on 14th April, a faction of the anti-Treaty IRA seized control of the Four Courts and several other strong points around Dublin city. There were skirmishes around the country with some loss of life as both sides vied to occupy the barracks the British were evacuating.

On Wednesday 03rd May, in an effort to reunite the IRA, five officers of the anti-Treaty IRA, mostly from the south, ‘who are trying to bring about unity in the Sinn Fein ranks’ appeared on the floor of Dáil Eireann. After a desultory debate it was agreed that a committee of 10 members (five from each side) should be selected to consider the officers appeal against civil war. The following members were selected:

| Anti-Treaty | Pro-Treaty |

| P Ruttledge | Sean Hales |

| Harry Boland | Patrick O’Malley |

| Liam Mellowes | Joseph McGuinness |

| Sean Moylan | Sean McKeon |

| Mrs. Kathleen Clarke – Chairman | James Dwyer – Secretary |

And a statement was issued by Seamus O’Dwyer

The Committee appointed by the Dáil held its first meeting this evening and recommended an immediate cessation of hostilities. Towards this end, Major-General Sean MacKeon and Commandant-General Liam Mellowes left to interview their respective headquarters. The Committee will reassemble at 10 o’clock tomorrow (Thursday) at the Mansion House.

Signed,

Kathleen Clarke (Chairman)

Seamus O’Dwyer (Secretary)

The next day, Thursday 4th May, the Committee and a Conference of Officers met at the Mansion House and a truce was agreed between the two sides until the following Monday to allow for a compromise to be negotiated. The Irish Times noted that “the general feeling was one of friendliness and good will”[7]and the Dáil Eireann Publicity Department issued the following statement;

The Committee reassembled this morning at 10 o’clock. Deputies McKeon and Mellows succeeded in bringing the respective Chiefs of Staff together, as a result of which a truce was arranged. In view of the fact that the Army chiefs are continuing their deliberations, it has been decided to adjourn until 12 noon on Friday at the Mansion house.

Signed,

Kathleen Clarke Seamus O’Dwyer

In the elections for the Third Dáil the pro-Treaty side comprehensively defeated their anti-Treaty opponents with 239,193 first preference votes cast for them, and only 133,864 cast for the anti-Treatyites. Dwyer stood as a pro-Treaty Sinn Féin candidate, but Tom Johnson, the Irish Labour Party leader, was elected in Rathmines instead.

The agreement that was worked out entitled each side to the same amount of Dáil seats as they had before the election. This would have ensured that, no matter what the result of the election, the Pro- and Anti-Treaty proportions of any coalition government set up after the election would have remained identical to those which prevailed in the (pre-election) Second Dáil. In the end the pact broke down because the British Government forced Collins to include the Oath of Allegiance in the new Free State constitution. De Valera and Collins had hoped to avoid the mention of the Oath thereby making the new constitution more palatable to both sides.

The pro-Treaty (Free State) side claimed that the election mandated their position. The anti-Treaty (republican) side claimed that as the new Free State constitution had only been published on the morning of polling day, and as Collins had broken the electoral pact at the last minute, the election was null and void. The country spiralled inevitably towards Civil War.

James Kavanagh, the Secretary of the ‘Defence of Ireland Fund’, Accountant to the Sinn Fein Executive and Secretary to the Local Government Department of Dáil Eireann, recalled Seamus Dwyer thus;

Seamus Dwyer was one who was in the thick of the movement. He favoured acceptance of the Treaty when it came before the Dáil, but, later on, when he saw the dissonance arising amongst erstwhile friends because of the Treaty, he expressed great sorrow and set about finding a means of bringing them together again despite the Treaty. He kept moving back and forward between the opposite groups to try and make peace. That’s what he told me anyway and I believed him.[8]

Civil War

On the 28th June 1922 the shelling of the Four Courts started and the Civil War, which Seamus Dwyer had tried so hard to stop, began. Mary Flannery Woods, an anti-Treaty officer in Cumann na mBan recounts how Dwyer was captured and imprisoned by Cumann na mBan/Na Fianna at the Fianna HQ at 41 York Street at the start of the Civil War.[9]

Dwyer was briefly imprisoned by republicans in the battle for Dublin in July 1922. Freed, he worked in some capacity for Free State Intelligence

“We had two prisoners in York Street, one of them a demented Jew. I was informed he was the man who had pointed out Sheehy Skeffington to Colthurst, who shot or ordered Sheehy Skeffington to be shot by his men. I forget how. The other was a Rathmines man … Dwyer was his name“.[10]

It is not possible to determine what caused Dwyer’s incarceration in York Street, or how long he was held. Presumably with all his to-ing and fro-ing between the different factions in the days leading up to the start of the conflict, he found himself in the wrong place at the wrong time when the fighting actually started.

Whatever the case, Dwyer was soon free again and in early August he features in a letter from Lieut. Charles Saurin to President WT Cosgrave regarding a committee for the ‘Organisation of Civilian Population’. In it Saurin says that he appreciates the honour of being chosen to act on such a Committee, but in a neat sidestep he says that ‘I would nevertheless suggest that Seumas (sic) Dwyer, of Rathmines, would be the right man for that position and I am perfectly willing to stand down in his place’.[11] This suggestion was accepted and Ernest Blythe was sent to see Dwyer.

On the 23rd November 1922 a Cabinet meeting was held to discuss the proposed setting up of a Citizens’ Defence Force. Those at the meeting included the Minister for Defence, the Director of Organisation and the Chief of Staff. The Cabinet records for the following day note that ‘The Minister for Home Affairs [Kevin O’Higgins] submitted a scheme for the setting up of a Citizens’ Defence Force to assist in the suppression of crime in the city of Dublin’ and that the scheme was approved. Seamus Dwyer must have declined the offer to head up this organisation as the Cabinet records for the following day note that Captain Harrison was appointed Supervisor of the CDF and Seamus Hughes its Intelligence Officer.

Oriel House

Oriel House, a prominent building in the centre of Dublin located on the corner of Fenian Street and Westland Row, was the headquarters of the Free State Intelligence Department which comprised of three sections;

- The Criminal Investigations Department (CID)

- The Protective Corps

- The Citizen’s Defence Force

The CID was an armed, plain clothed counter-insurgency police unit which was formed shortly after the Truce as a quasi-military organisation under the control of the Intelligence Department of the Free State Army. At its peak it consisted of some 120 heavily armed men, many of whom were former IRA fighters who had been close to Collins during the War of Independence, including some members of the Squad. Closely allied with it was The Protective Corps which was set up to protect Government Buildings, TD’s, Senators and other prominent supporters of the Government.

The Citizens Defence Force consisted of 101 members, mostly ex-British Army men who were probably recruited from the British Legion. They duplicated some of the work of the Protective Corps, guarding banks and cinemas and patrolling the streets of the city. They never revealed their names when submitting reports, using a personal number instead.

Republicans alleged Dwyer was responsible for a number of their men being executed and for this he was assassinated on December 20 1922.

In addition to acting as bodyguards for figures in the Free State whose lives were threatened, they also organised the guard posts at important public buildings and, more importantly, were embedded into Free State army units to ensure discipline and loyalty.

Though there is no record of Dwyer having an official position in the CDF, it is clear that he was strongly associated with it in the minds of the Republicans, Sean Dowling was later to state that ‘…Dwyer was carrying on undercover work through a group the Citizens Protection Association’. Similarly, there is a statement in the Sean O’Mahony papers to the effect that, “Dwyer was not an ordinary shop keeper; he had been doing undercover work with the Citizens’ Protection Association for the Staters, laying traps and having activists arrested and at least one volunteer Tony O’Reilly from Celbridge, executed.[12]

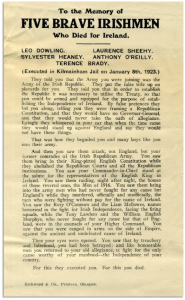

This last statement is hard to justify as Tony O’Reilly was one of five National Army deserters who had defected to the Republican side following an abortive attack on Baldonnel Aerodrome. They were captured in Kildare on 1st December 1922 following the ambush of a broken down National Army lorry at Collinstown on the Leixlip to Maynooth Road.

In a follow up operation some 22 Republican soldiers were captured and taken to Kilmainham Gaol. There O’Reilly and his four fellow deserters, were court-martialled in Kilmainham on 11th December, sentenced to death and shot on 8th January 1922.

The attack on the Army lorry was completely opportunistic and it is hard to see how Seamus Dwyer could have been involved in laying any traps to capture O’Reilly and his comrades. Whatever the case, Dwyer’s close association with the CDF and Oriel House meant that he was marked for execution. The IRA even had a spy working for him in his grocery. According John Callinane, Jimmy Kenny, then a member of the Dublin IRA’s A Company, 4th Battalion and later one of the infamous Broy’s Harriers, was an assistant in Dwyer’s shop.[13]

A Visit, A Question & A Deadly Aim

On the evening of Wednesday 20th December 1922 Seamus Dwyer was 37 years of age, still married to Marie but, despite some eight years of marriage, without children. As the day’s trading drew to a close Marie was upstairs in their accommodation while her husband served customers and spoke with friends in the shop below.

It was only five days before Christmas, no doubt trade was brisk and Dwyer was looking forward to the Christmas break. It was also the day after seven Republican prisoners had been executed in Kildare following their capture carrying arms, one of the largest single executions during the Civil War.

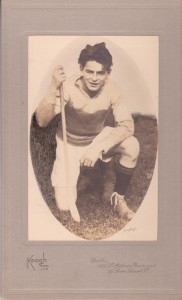

In the gathering dusk Robert Bonfield closed the door at his home and walked the short distance from his house on Moyne Road, Ranelagh to James Dwyer’s spirit grocery at 5 Rathmines Terrace. Bobbie Bonfield was a twenty year old dental student in the third year of his studies at UCD, an excellent hurler and the Quarter Master and Acting O/C of the 4th Battalion, 1st Dublin Brigade of the IRA. He was also a ruthless, experienced and committed guerrilla fighter. On that fateful evening he was dressed in a dark overcoat and concealed his face by turning his collar up and wearing a soft black hat. He was wearing black boots and had a revolver in the breast pocket of his coat.

“Are you Mr.Dwyer” Dwyer replied, “Yes” Bonfield said “I have a message for you”, and shot him.

As Bonfield entered Dwyer’s shop just before 5 p.m., Dwyer was standing behind the counter chatting to a neighbour, Walter Foley, the Manager of Messers. Edward Lee & Co, the drapery shop next door. There were three other assistants in the shop, one of whom was possibly the spy James Kenny. Thinking that a customer had entered the shop Foley finished the conversation and moved away from the counter. Bonfield went directly to Dwyer and asked;

“Are you Mr.Dwyer”

Dwyer replied, “Yes”

Bonfield said “I have a message for you”

Standing less than a yard away from his victim, Bonfield reached into the inside breast pocket of his overcoat and whipped out the revolver, pointed it directly at Dwyer’s chest and fired two shots into him from point blank range. Dwyer was hit in the heart and died instantly, falling behind the counter.

Startled by the gunshots, Foley turned and, as he did so, Bonfield rushed past pointing the gun directly at him. Thinking Bonfield was going to shoot again, Foley ducked and Bonfield ran out of the shop onto the busy Rathmines Road. Foley ran after him shouting “Stop that man” in the hope that people on the street might apprehend the assassin.

Constable Maurice Aherne of the DMP, on traffic duty at the junction of Castlewood Avenue and Rathmines Road, less than fifty yards from the scene of the shooting, heard the shots and immediately gave chase with a large crowd following behind.

But Bonfield was a fit hurler and sprinted away, ducking into an entrance between Kennedy’s coal store and Murray’s tobacco shop, an alley known locally as the ‘Hole in the Wall’, through the corridor of a tenement house and made good his escape in the direction of his home on Moyne Road.

The whole incident probably took less than two minutes and he could have made it back to his own home less than fifteen minutes after firing the fatal shots.

Aherne and Foley returned to the shop where they found Dwyer slumped behind the counter, his head cradled by a number of friends and blood streaming from his chest. A medical student had been passing the shop at the time of the shooting and had rushed to assist, but Dwyer was beyond help. A telephone call was made to the Rathmines Ambulance and his lifeless body was taken to the Meath Hospital.

Three days later, on Saturday 23rd December, just two days before Christmas, there was a large and impressive funeral ceremony for Dwyer with a military guard. Funeral mass was celebrated at 10 o’clock the Church of the Immaculate Conception, Rathmines by Fr. Murnane after which Dwyers’ remains were removed to Glasnevin cemetery.

As it left the church the cortege stopped outside Lissonfield House, the residence of the Commander-in-Chief, General Mulcahy, and a number of officers of the high command of the Free State Army, with an escort of troops, joined the procession. There were widespread demonstrations of sympathy and respect as the cortege passed: all shops and businesses in the district were closed and blinds were drawn in private houses. Crowds of people lined the streets and stood silently as the hearse passed. As the funeral neared the Town Hall the building was closed and its blinds drawn.

Dwyer was survived by his wife, mother, twin brother Luke, then living at 3 Vernon Avenue, Booterstown, two younger brothers, Dr. William Dwyer and Eddie Dwyer, and two sisters, Mrs. Byrne of Limerick and Miss May Dwyer. The chief mourners were John O’Brien, Luke O’Brien and P O’Brien (cousins). The 4th Battalion of the Dublin Brigade were represented by Commandant FX Coughlan, Capt. HS Murray, Capt. Donigan, Capt. P. Coghlan and Lieut. M Doyle.

Rev. M Fitzgibbon read the prayers at the cemetery and later that day the Committee of Management of the New Ireland Assurance Society passed the following resolution: “That we deeply mourn the loss of our dear colleague on this Committee and beg to tender to Mrs. Dwyer our very sincere sympathies in her great affliction”.

His death was noted in the records of Blackrock College by Fr John Ryan CSSp, College historian and archivist: ‘Shot 1922 (see Necrology). Political assassination – connected with his attitude re killing of Rory O’Connor?’ The Necrology for 1922 lists James Dwyer’s name with the word “shot” added later in Fr. Ryan’s hand.

His friends were puzzled as to why Dwyer had been shot. James Kavanagh thought that he had been trying to end the Civil War; ‘However, there must have been others who did not, for one evening he was shot dead in his shop, a high-class grocery on the Rathmines Road’.[14] Republicans, on the other hand seem to have felt he deserved his fate. Mary Flannery remembered of the man whom she had once held prisoner on York Street, ‘He was shot later by the I.R.A. as a spy … I was sorry for him for he had been in jail with my son Tony. But I was told I needn’t grieve for him for he was ripe for killing.[15]

Free State Reaction

The official reaction of the Free State Government to the killing of such a prominent ex-politician was surprisingly muted, particularly when compared to the recent attack on 7th December in which the TD Sean Hales was killed and another TD,Pádraic Ó Máille, wounded. Following that incident the Provisional Government immediately held an emergency Cabinet meeting and decided on the retaliatory execution of four prominent Republican leaders – members of the IRA Army Executive – Rory O’Connor, Liam Mellows, Richard Barrett and Joe McKelvey.

They had been in custody since the capture of the Four Courts at the beginning of the Civil War more than five months before and could have had no involvement in the attack on Hales and Ó Máille. They were shot the following day.

Two republicans, Frank Lawlor and the actual assassin, Bobby Bonfield, were later killed by clandestine Free State forces in revenge for the shooting of Seamus Dwyer.

The backlash to those killings, and the fact that Dwyer was not a sitting TD, meant that the government were not in a position to respond in the same fashion as they had previously. But while there was no authorised response to Dwyer’s death, the unauthorised response was swift and equally as brutal as Dwyer’s killing itself.

The authorities seemed not to know who was involved but they hit back ruthlessly, Republican Volunteer Frank Lawlor was abducted from his home in the city centre shortly after Christmas 1922, taken to the outskirts of the city and shot on Orwell Road in Dundrum on the city boundary and adjacent to the golf links at Milltown.

Francis ‘Frank’ Lawlor was a Section Commander in D COY, 3rd Battalion, Dublin Brigade. He had joined the IRA in 1918 and had fought through the War of Independence. Lawlor apparently had a lovely tenor voice and had sung at the Christmas mass in Haddington Road Church just days before.[16]

According to friends at his inquest, he knew that the CID were looking for him and was on the run. But three days after Christmas, on the night of December 28th 1922, the CID pulled him from a friend’s house in Ranelagh where he had been hiding. According to Cahir Davitt, the first Advocate General of the National Army;

“A party of armed men, who described themselves as acting on behalf of ‘the Authorities’, called at the lodgings of a man called Francis Lalor (sic) and forcibly took him away. His dead body was found the following morning in the vicinity of Milltown Golf Course. This killing had all the appearance of being an ‘unofficial execution’ carried out by some members of the Government’s forces”.[17]

It would seem that Lawlor was killed in reprisal for the shooting of Dwyer. Mary Flannerry Woods, the anti-Treaty Cumman na mBan activist, stated that Dwyer, “was shot by the IRA as a spy and for whose shooting, Frank Lawlor was murdered on the golf links at Milltown”.

Years later, James Kavanagh, a friend of Dwyer’s, asked a pro-Treaty acquaintance if they had ever found who killed Dwyer, “he told me that they had … he couldn’t remember the fellow’s name but that his body was found in a ditch up at Milltown. The name of the man whose body was found in Milltown was Frank Lawlor who, from what I was told afterwards, could not have shot Seamus Dwyer as he was in another place when Dwyer was shot”.

An interesting point to note is that the memorial stone marking the spot where Lawlor’s body was found is located about a meter away from a stone marking the City/County boundary. Making sure that the killing was done outside of the city boundaries is a feature of several of the killings at this time, including that of Bobbie Bonfield who did not survive much longer.

At about 5 pm on Holy Thursday, 30th March 1922, less than three months after he had assassinated Dwyer, Bonfield was on his way into the city centre to pick up orders from a newsagent that was used by the anti-Treaty forces as a drop shop. At the junction of Lower Leeson Street and St. Stephen’s Green he bumped into President WT Cosgrave and his bodyguards who were visiting the seven churches, a traditional Easter devotion at the time.

The group recognised Bonfield and there was a brief altercation on the street outside of St. Vincent’s Hospital. One of the bodyguards produced a revolver, Bonfield raised his hands and he was dragged towards the Baggot Street corner of the Green, near the Shelbourne Hotel, and in the direction of both Oriel House and the new CID Headquarters which was just a few hundred yards away on Merrion Square. An hour and a half later, between 6:30 and 7 pm, a young girl named Bella Brown who lived near the Red Cow in Clondalkin heard six shots as she was bringing milk to a neighbour’s house. The following day the body of Robert Bonfield was discovered in a field close by, he had been shot several times in the head.

In April 1923, perhaps by way of counter-reprisal, Dwyer’s spirit grocery shop in Rathmines was substantially damaged when an IRA mine destroyed the adjoining building occupied by Messers. Edward Lee &Co.[18] The manager of Lee’s, Walter Foley, had been speaking to Dwyer immediately before he was shot by Bonfield.

Robert Bonfield is commemorated by a small memorial on the Naas Road which was recently removed by the National Graves Association as part of the road widening associated with the construction of the new flyover at Newland’s Cross. The memorial will be reinstated when the roadworks are completed and a re-dedication ceremony is planned.

His victim James Dwyer has been largely forgotten.

Michael McKenna is an independent researcher with a particular interest in events in Dublin during the Irish Civil War and a distant relative of Bobbie Bonfield.

References

[1]WS993 – Cahir Davitt, Advocate General of the National Army

[2] Mary Flannerry Woods – Witness Statement ; Dan Bryan – Witness Statement WS0947

[3]O’Farrell, Padraic – Who’s Who in the War of Independence 1916-1921 –Mercier Press, 1980

[4]Maume, Patrick – James MacMahon – Dictionary of Irish Biography, Cambridge University Press

[5]Yeats,Padraig –City In Turmoil

[6]McCarthy,Cal- Cumann na mBan and the Irish Revolution – p. 173

[7]Irish Times, 5th May 1922 p. 5 – Truce Till Monday

[8]WS0889 – Seamus UaCaomhanaigh / James Kavanagh – Page 147

[9] WS0624 – Mary Flannery Woods – Page 72

[10] The O/C at York Street at the start of the Civil War was Joseph O’Connor. O’Connor joined the Irish Volunteers in 1913 and by 1916 he was a captain in command of A Company, 3rd Battalion, Dublin Brigade under Éamon de Valera. When the vice-commandant failed to show for the 1916 Easter Rising de Valera made O’Connor his second in command. O’Connor remained with his company and de Valera at Boland’s Mill until they became the last battalion to surrender. He was imprisoned at Frongoch internment camp in Wales and released in the 1917 amnesty. Returning to Dublin O’Connor joined ‘The Squad’ under Michael Collins and killed Captain John FitzGerald of the ‘Cairo Gang’ on Bloody Sunday in 1920. By the end of the Irish War of Independence he was Commandant of the 3rd Battalion ‘Dev’s Own’. He was a member of the Irish Republican Army’s ‘Banned Convention’ in 1922 and in the Battle of Dublin during the Irish Civil War he held the Fianna HQ in York Street near St Stephen’s Green. He escaped to Limerick and succeeded Ernie O’Malley as the Quarter-Master-General of the IRA with the rank of Brigadier-General.

[11]Letter from Lt. Commdt. Charles Saur into WT Cosgrave dated 01/08/1922 NA S1410

[12] Sean O’Mahony papers, National Library of Ireland (MS/44,055/10)

[13] Ernie O’Malley Notebooks – John Callinan – P17b/106

[14]WS0889 – Seamus Ua Caomhanaigh / James Kavanagh – Page 147

[15] The O/C at York Street at the start of the Civil War was Joseph O’Connor. O’Connor was born in the 1880s and remembered seeing Charles Stewart Parnell as a child. He joined the Irish Volunteers in 1913 and by 1916 he was a captain in command of A Company, 3rd Battalion, Dublin Brigade under Éamon de Valera. When the vice-commandant failed to show for the 1916 Easter Rising de Valera made O’Connor his second in command. O’Connor remained with his company and de Valera at Boland’s Mill until they became the last battalion to surrender. He was imprisoned at Frongoch internment camp in Wales and released in the 1917 amnesty. Returning to Dublin O’Connor joined ‘The Squad’ under Michael Collins and killed Captain John FitzGerald of the ‘Cairo Gang’ on Bloody Sunday in 1920. By the end of the Irish War of Independence he was Commandant of the 3rd Battalion ‘Dev’s Own’. He was a member of the Irish Republican Army’s ‘Banned Convention’ in 1922 and in the Battle of Dublin during the Irish Civil War he held the Fianna HQ in York Street near St Stephen’s Green. He escaped to Limerick and succeeded Ernie O’Malley as the Quarter-Master-General of the IRA with the rank of Brigadier-General.

[16]O’Dwyer, Martin – Death Before Dishonour (2010)

[17]WS993 Cahir Davitt, Advocate General of the National Army

[18]WS993 – Cahir Davitt, Advocate General of the National Army, page 74