Today in Irish History, Bloody Sunday, 21 November 1920

November 21, 1920. A day of bloodshed in Dublin marked the escalation of the Irish War of Independence. By John Dorney. See also Four Bloody Sundays.

The Purge

James Cahill was a young IRA gunman, attached to D company of the 2nd Battalion, Dublin Brigade. Originally from Cavan, he had been transferred to Dublin after coming to the attention of the local RIC, who had ordered his employer to let him go.

In Dublin, his routine work was to carry out clandestine armed patrols with his company around O’Connell Street. On the night of November 20, 1920, however, he received new orders from his IRA company commander Paddy Moran; to kill, early the next morning, three British Intelligence officers who slept in the Gresham Hotel on O’Connell Street.

Michael Collins, IRA Chief of Intelligence had drawn up a list of 50 Intelligence officers and their informants to be killed that morning, but after objections from Cathal Brugha, the Dail’s Minister for Defence, the list was whittled down to 35.

Cahill in his recollections called the operation a ‘purge’, -clinical, ruthless – and so it was.

At nine o’clock that Sunday morning, nine men from Cahill’s D company set out from Parnell Square to the Gresham, maybe five minute’s walk away. Three of them, Cahill himself, Nick Leonard and Mick KilKelly were to be the assassins, the other six were to hold the hotel staff until the shooting was finished.

Cahill was disconcerted to hear a newsboy call him by name on the way into the hotel, but another shouted, ‘there’s a job on, best clear out’. It says something about the atmosphere in Dublin at the time that the teenaged newspaper sellers had internalised both the language and the modus operandi of the IRA.

Cahill had recovered his composure by the time he and Mick Kelly came across a, ‘man of foreign appearance’ in the corridor. When asked his name he replied, apparently thinking they were police, ‘Alan Wilde, British Intelligence Officer, just back from Spain’. Kelly shot him dead.

James Cahill and Nick Leonard then burst into the unlocked room of Patrick McCormack. McCormack, sitting up in bed, fired his .38 revolver at the intruders but the bullet buried itself in the wall between them. Cahill and Leonard fired together at close range, ‘killing him outright’.

Their third target was not be found in his room. Cahill remembered that, ‘the usual Sunday morning calm prevailed in O’Connell Street’ and the IRA party quietly slipped away.[1]

It has been sugested that neither Wilde nor McCormack were actually Intelligence officers at all. Wilde may have been an ‘oddball civilian’, while McCormack, an Irishman, was a British Army officer in the Veterinary Corps but appears to have been in Dublin to buy horses for the Alexandria Turf Club. James Cahill though, remained convinced they had shot the right men.

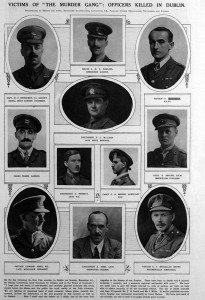

The IRA assassinated 14 British officers and others that morning in Dublin

All over central Dublin that morning, the IRA had been out, (both the Squad and as at O’Connell Street, the Dublin Brigade) shooting the mostly unsuspecting agents in their beds. Between ten and twelve British officers were dead, as were two more Auxiliaries who had stumbled across one of the shootings on Mount Street and either one or two civilians. Another British Intelligence officer died later from his wounds and four more were shot but not killed.

The toll could have been heavier still but as Todd Andrews remembered, “the fact is that the majority of the IRA raids were abortive. The men sought were not in their digs or in several cases, the men looking for them bungled their jobs”.[2]

It had been a gruesome business – the killing up-close, personal and premeditated. For some of the of the IRA volunteers involved, the killings presented no problems. Some were disappointed when they heard that so many of their targets had survived.

Others though were deeply traumatised. Seventeen year old IRA member, Charlie Dalton, ‘couldn’t sleep the night of Bloody Sunday, he thought he could hear the gurgling of the officers’ blood’. He recalled he, ‘could no longer control the overpowering urge to run, to leave far behind me those threatening streets ’.[3]

‘A disgraceful show’

The British of course expressed outrage. In private however, Lloyd George, the prime minister expressed the hope that it would not derail private peace negotiations he was having, via intermediaries with Arthur Griffith. ‘These men were soldiers’, he said of the dead, ‘and took a soldier’s risk’.[4]

On the ground in Dublin, however, the British forces were less sanguine. At Dublin Castle, when news of the morning’s shootings came in, ‘panic reigned’. ‘The gates were choked with incoming traffic, the military their wives and agents’.[5]

By the afternoon, many were burning for revenge.

At about 3:25, a Dublin Metropolitan Policeman stationed on Jones Road, saw nine or ten military lorries and three armoured cars pull up outside Croke Park, where about 5,000 people were watching Dublin play Tipperary in Gaelic football. Out of the lorries spilled soldiers and about 100 men in the dark green uniforms of the RIC.

The intention of the British operation seems to have been to search the crowd for IRA suspects and indeed, several of those who had done the shooting that morning, among them Squad members, Tom Keogh, Dan McDonnell and Joe Dolan, were at the match. However, little attempt seems to have been made to actually look for armed men. The RIC claimed they were fired on by the crowd, but the DMP policeman was clear that they started firing as soon as they had dismounted their lorries.

At Croke Park, ‘The Black and Tans fired into the crowd without any provocation whatsoever’, killing 13.

Once they saw young men running from them outside the ground (apparently ticket sellers) the police opened fire. Chasing the men into Croke Park, they blazed away at the crowd and the players – 228 rounds were fired – killing 13 and injuring some 60 more.

The shooting provoked mayhem inside the crowd, people threw away their overcoats to run faster and trampled over one another to get away. Two more people were crushed to death in the stampede. To add to the pandemonium, one of the armoured cars fired 50 rounds from its machine gun over the heads of the fleeing spectators.

It is still not entirely clear whether the shooting was done by Irish RIC constables, new recruits or ‘Black and Tans’ or the RIC Auxiliary Division or all three. One RIC officer later told the Auxiliary Division’s commander, Crozier, that the Black and Tans had started the shooting; ‘It was the most disgraceful show I have ever seen, the Black and Tans fired into the crowd without any provocation whatsoever’.[6]

Two high level Dublin IRA members, Dick McKee and Peadar Clancy, as well as a civilian friend of theirs, Conor Clune were picked up that night by Auxiliaries, beaten and ‘shot while trying to escape’, in Dublin Castle.

Ernie O’Malley, an IRA man, recalled the atmosphere of fear and foreboding that night in Dublin. ‘The troops had blood in their eyes… Soldiers and Auxiliaries were firing over the moving people, “Go home you bastards go home”… We talked in whispers, as if afraid of the sound of our own voices’, outside in the street the noise of heavy cars and sharp commands’.[7]

Terror and counter-terror. After Bloody Sunday in November 1920 it was clear that the conflict we now call the Irish War of Independence would be a long and brutal affair.

For a longer consideration of the day’s events see Bloody Sunday 1920 Revisited.

References

[1] James Cahill, Bureau of Military History Statement, file S. 1760

[2] Dwyer, T Ryle, The Squad and the Intelligence Operations of Michael Collins, p90

[3] Daly, Anne, Ending War in A Sportsmanlike Manner, in Turning Points in Twentieth Century Irish History, p33

[4] Hopkinson, Michael, The Irish War of Independence, p180

[5] Dwyer, T Ryle, The Squad and the Intelligence Operations of Michael Collins, p86

[6] Dwyer, p188-191

[7] O’Malley, Ernie, On Another Man’s Wound p237-239.

Thanks to The Cairo Gang website for use of the image above.