The UCC Civil War Fatality Project – Counting the dead of the Irish Civil War

By John Dorney

During fighting between pro and anti-Treaty forces in Limerick city in July 1922, Catherine Sexton was penned in her home in Quarry Lane, Garryowen. She was the 60-year-old widow of a stone mason.

During a lull in the fighting, she ventured outside her home for water. Piped water was still a thing of the future in many working-class homes in 1922. On her way to or from the well, she was hit by stray bullet in the arm. Evacuated to St John’s Hospital, she developed blood poisoning and died of her wounds on July 28.[1]

She was one of 1,485 fatalities logged by the new Irish Civil War Fatalities project of University College Cork (UCC) between June 28 1922 and May 24 1923.

Ther were 1,485 fatalities logged by the new Irish Civil War Fatalities project of University College Cork (UCC) between June 28 1922 and May 24 1923.

The project, headed by Andy Bielenberg of UCC, was formally launched on April 29 2024 at the National Universities of Ireland building on Dublin’s Merrion Square. It is now searchable on the UCC website, where users can browse the list of dead as well as an excellent interactive map put together by Michael Murphy and the geography department of UCC.

One can read elsewhere our findings, based on statistics; geographical distribution, cause of death, gender and social class. What I want to do in this short piece is rather to talk about the human experience of researching the dead of the Irish Civil War.

Commemoration

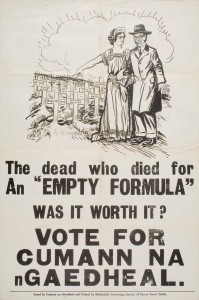

One of the first, striking things was the disparity between the desire of pro and anti-Treaty sides to remember their dead. Apart from the fallen leaders such as Michael Collins and Arthur Griffith, the pro-Treaty or Free State side appear to have been actively opposed to enumerating, much less commemorating their dead soldiers.

When in 1927, families of National Army soldiers from Cork and Kerry, who were killed in County Limerick, lobbied to have them disinterred and brought back to Cork, the Army command was most reluctant.

Though they noted that the ‘irregulars’ (anti-Treatyites) had made ‘repellent’ ‘political capital’ from the reburial of their men they did not think that the Free State’s military should follow suit. It would be a ‘gruesome business’ that would ‘not have a beneficial effect on the public mind’.[2]

The defeated republicans were far more enthusiastic about commemoration

A plaque to the National Army soldiers buried at Glasnevin cemetery in Dublin was not installed until 1957 and it was not until 1968 that a monument with names inscribed on it was finally erected. Though there are 183 names inscribed on the Civil War monument there now, there may be other bodies buried there. At one point it was suggested that the plot contained the remains of 214 soldiers. By the 1960s no one appears to have known the true number.

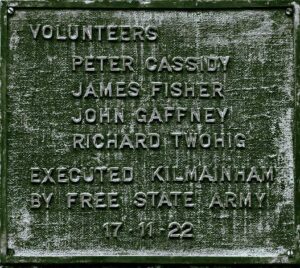

The anti-Treaty side by contrast were from the start very keen to memorialise their fallen. An IRA directive of 1924 for instance, orders all units to assemble lists of the Civil War dead for a prospective memorial book named Leabhaer na hAiseigie.[3]

Oddly it was easier to commemorate those who died for a lost cause than a victorious one.

Among the fallen

This may have skewed our perception of the Civil War somewhat, as our statistics show that pro-Treaty losses were over a third higher than anti-Treaty ones (648 deaths to 438). The pro-Treaty soldiers were far more likely to be killed in action, or (all too commonly) accidentally killed by themselves or their comrades.

Researching Civil War fatalities is to come across a numbing series of small tragedies. Patrick Mulhall, for example, was a 19 year old telegraph operator from Dublin. He had no previous military service in the IRA, with British forces or with anyone else. Perhaps he was unemployed, as many were, when he joined the National Army. Or perhaps he wanted a taste of adventure and risk. He was accidentally shot dead by a fellow soldier during an operation on the Dingle peninsula in Kerry on 19 December 1922. [4]

Not all of the pro-Treaty soldiers came from an impoverished or working class background however. Among them was Eugene McQuaid, an assistant medical officer in the Army, taking a break from his work as a ‘surgeon probationer’, who was shot and mortally wounded in an action between Shramore and Westport, Co Mayo, on February 23, 1923. He was the brother of the future Catholic Archbishop John Charles McQuaid, whose influence was so pervasive in independent Ireland.[5]

To research Civil War dead is to assemble many small tragedies

Though the anti-Treaty side lost a smaller number of combatants, the circumstances of their deaths were often disturbing. Nearly half were executed or summarily killed after capture. One of the 81 executions we logged was Patrick Russell, a 26 year old farmer’s son from county Tipperary. He was executed by Free State firing squad at the Castle Barracks, Roscrea on 15 January 1923, having been sentenced to death for ‘having held up a mail car armed ‘. Like most anti-Treaty fatalities, over 70 per cent in fact, he had served in the IRA also during the War of Independence.

John Fleming, a 29 year old painter, of Tralee and like Russell, a veteran of the pre-Truce IRA, was shot by his captors while a prisoner at the National Army post at the workhouse in the town and secretly buried. When his body was discovered, the Army reported, almost certainly falsely, that he had been ‘shot while attempting to escape as he was being transferred from Ballymullen Goal to Hourihane Barracks in Tralee’. [6]

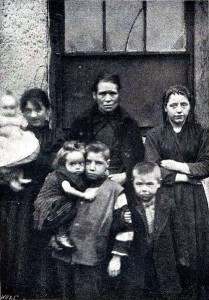

One of our standout findings is that civilian fatalities, 371, in the Civil War, were only about third of those in the preceding War of Independence. This did not, however, make the official treatment of the families of those civilians caught up in the conflict any more generous.

David Nolan, for example, a 52 year old secretary at Lee Boots Manufacturing Company in Cork had the bad luck to be riding in a horse drawn trap on Washington Street on 26 October 1922, when the IRA launched a gun and grenade attack on a National Army lorry. The lorry, swerving to avoid the bombs and bullets, smashed into the horse drawn vehicle, leaving David Nolan with head injuries which turned out to be fatal. There followed a long correspondence with the Department of Defence, who denied that the army was in any way liable for the incident and refused compensation for his family from that department. [7]

Assassination of civilians was rare, compared to the preceding conflict of 1919-21, but no less shocking for that. The pro-Treaty army reported on February 7 1923, for instance, of the shooting, at Mulinahone Co Tipperary, of Owen Cashin, aged ‘about 40’, a ‘relative of Captain Cashin’. Owen Cashin was taken from his car in which his wife and himself were travelling. He was shot and his body dumped on the roadside, bearing the label ‘first of fifty convicted spies’.[8]

Individual examples of fatalities could be cited almost indefinitely, as long as the list of dead itself. Each one was, of course a person, once with their own hopes, fears, dreams and plans, a loss to a family and loved ones, a life taken by violence.

A social history of death?

But one impression this researcher was left with was the relative rarity of Civil War violence. A large portion of the research involved scanning over pages and pages of death registers, searching for violent deaths. For short periods, such as for instance, the week-long battles in Dublin and Limerick cities in July 1922, deaths by bullets or (more rarely) bombs dominated the entries. But elsewhere and thereafter, they were much, much rarer. Some counties such as Wicklow, Cavan and Longford had virtually no Civil War deaths.

For all that fear stalked many rural and some urban areas in 1922 and 1923, one was far likelier to die of tuberculosis or pneumonia, heart disease or even farm accidents than Civil War violence in those years.

To scour the death registries is also to get a snapshot of the ill-health of the general Irish population at that time. Particularly in the cities, people died at shockingly young ages by modern standards, often in their 40s and 50s. When one comes to pages referring to a Poor Law Union or workhouse, a great many deaths occur in people’s 20s and 30s.

Researching the project meant being exposed to everyday death, which far outnumbered those killed by Civil War violence.

Illness also accounted for the deaths of about 200 National Army soldiers, who were not counted as Civil War casualties in our study.

Rural areas were healthier than cities, with far more deaths in old age, in people’s 70s or 80s. But there one is struck by the paucity of medical health available. Many died at home and it was some time before a doctor was able to attend. A common rural cause-of-death entry starts with ‘probably’ as the deceased were examined some time after death had occurred and it was often not possible to determine exactly how they had died.

The research also threw up violent, tragic deaths that could not be counted as victims of Civil War violence. Annie Doyle of Kilkenny, aged 23, for instance, poisoned herself in September 1923 having been spurned by National Army sergeant, Jack Manning, with whom she had ‘lived as man and wife’. Her suicide note to her mother read that Manning was ‘going about with other girls and making little of me. I cannot stick it. He said he would do this to me so I wrote this before he done it. Goodbye and try to forget me as I am nearly out of my mind’.[9]

Those who died by their own hands were generally classed as having suffered from ‘temporary insanity’ to spare their families the ignominy of a verdict of suicide.

Working on this project was in some ways a gruesome experience, but it was also an enlightening and rewarding one. With much firmer data now assembled, the history of the Civil War, the closing phase of Irish revolution, can now be discussed more dispassionately and precisely. But one cannot close a reflection on it without an appreciation of human pain caused by violent political conflict.

Though the death toll of the Irish Civil War appears to have been less than the Irish War of Independence, let alone other European Civil Wars of the era, the real question may be, whether so many really had to die in the dispute over the Anglo-Irish Treaty.

Listen to our podcast on this topic here:

References

[1] National Archives of Ireland (NAI) Department of Justice files JUS 2017/46/371

[2] Military Archives Reports, Cork Command, CW/OPS/04/24

[3] Twomey Papers UCD P69/20

[4] MSPC 2D339, death cert

[5] Dominic Price, The Flame and the Candle, War in Mayo 1919-24, p.248, MSPC 3D110

[6] National Army reports, Kerry command, CW/OPS/08/03, MSPC DP3527

[7] DOD-A-0893

[8] Military Statistics Summary Nov 1922-April 1923, Military Archives, MIPR-02-42

[9] Military Archives, Department of Defence requests for compensation DOD-A-10137

If you enjoy the Irish Story and wish to support our work, please considering contributing at our Patreon page here.