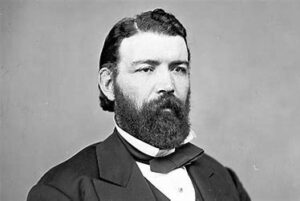

John ‘Old Smoke’ Morrissey the man who ordered the death of Bill ‘the Butcher’ Poole.

By John Joe McGinley

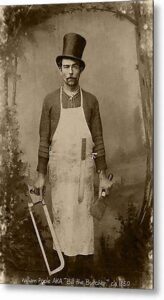

One of the most famous characters who inhabited the violent landscape of the Five Points Irish enclave of lower Manhattan in New York was Bill ‘the Butcher’ Poole.

An outspoken opponent of Irish Roman Catholic immigration into the United States, his notorious gang the Bowery Boys was feared by many Irish men and women who settled in New York. His career was brought to the attention of modern audience in the Martin Scorsese film ‘Gangs of New York’, which depicted ‘the Butcher’s end coming in a gang brawl amidst the New York draft riots of 1863.

John Morrisey was a boxer and gang leader turned political figure, who in 1855 ordered the death of rival gangster and nativist leader William Poole.

In fact, however, Poole’s reign of terror was ended nearly a decade earlier n 1855, when he was shot and fatally wounded on the orders of John ‘Old Smoke’ Morrisey the leader of another Irish gang, the Dead Rabbits.

Morrissey had a remarkable life in his own right, he was at times a gang leader, brothel owner, bare-knuckle boxing champion of the world and even a US Congressman.

This is the story of Morrissey and how he ordered the killing of Bill ‘the Butcher’ Poole.

A new life in America

Born in Temple, Co Tipperary on February 12, 1831, John Morrissey would soon leave his native Ireland with his parents bound for the United States. In early 1833, his family settled in the town of Troy in New York State. By 1850 the Albany-Schenectady-Troy metropolitan area was home to perhaps 1 million foreign-born individuals from more than 75 countries. About one in five were Irish, the largest ethnic group in the region. (1)

The young Morrissey did not spend much time in any formal schooling. John worked in a mill from a young age. At 12 he became an iron worker due to his physical size and tolerance for demanding work. In his early teens, due to this massive physique, which made him look much older than he was, he found himself working as a bouncer in a Troy brothel.

Morrisey was born in Tipperary but his parents emigrated to America when he was just two years old and settled in Troy, New York.

It was here that, in between sorting out wayward clients, Morrissey taught himself how to read and write. Realising his future was limited in Troy, it was not long before a young John Morrissey was drawn to the Irish American enclaves of New York City itself.

Not much is known of Morrissey’s early time in New York, but he later recounted that he spent his first few years learning to fight in bar rooms and on the gambling riverboats, which frequented the New York wharves.

Later in life, his political enemies would claim that as a youth he had been indicted twice for burglary, once for assault and battery, and once for assault with intent to kill. (2)

Moving to New York city as a young man, Morrisey made a name as a boxer, gang leader and political enforcer

Along with many other young men of Irish descent, Morrissey joined the Irish street gang, the Dead Rabbits. Their emblem, a rabbit impaled upon a staff, was carried into their wild street fights, hoisted proudly as a flag of war. Morrissey’s physique and prowess in brutal street fights as part of the gang, convinced him to pursue a career as a professional prize-fighter as well as a criminal enforcer.

Friends would later recount that he had his first fight in Captain Isaiah Rynder’s saloon, at 28 Park Row. Captain Rynder worked for the Tammany Hall Democratic party faction. His job was to arrange general mayhem and ballot-box stuffing to ensure victory for the right candidate. He was always on the lookout for young men with fighting skills to join Tammany Hall and he found one in John Morrissey.

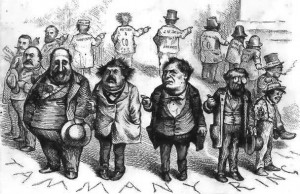

Tammany Hall, or simply Tammany, was the name given to a powerful political machine that essentially ran New York City throughout much of the 19th century. The organisation reached a peak of notoriety in the decade following the American Civil War, when it harboured ‘The Ring,’ the corrupted political organisation of William Magear Tweed, known as ‘Boss Tweed.’

Tammany Hall was the archetype of the political machines that flourished in many American cities in the late 1800s and early 1900s. Tammany Hall’s popularity and endurance resulted from its willingness to help the city’s poor and immigrant populations. Irish immigrants forced Tammany Hall to admit them as members in 1817, and the Irish thereafter never lost their tie with it. Many young Irishmen began their political or criminal career running errands for Tammany politicians and helping to sway elections by any means necessary.

Tammany Hall was the Democratic Party headquarters in New York. Many young Irishmen began their political or criminal career running errands for Tammany politicians and helping to sway elections by any means necessary.

Like all political machines, Tammany worked on the “spoils system.” An election victory brought the spoils, or rewards of success–about 12,000 city jobs to fill, as well as state and federal positions. Tammany politicians also bullied local companies for more jobs, which ward leaders handed out. Such power fed the corrupt machine. Tammany politicians may have helped struggling immigrants, but usually to enrich themselves. (3) The influence of Tammany did not wane until the 1930s and the organisation itself did not cease to exist until the 1960s. (4)

Morrissey would soon be part of this Tammany machine. When organising a local illegal bare-knuckle fight, Captain Rynder asked if any prize fighters were present in his bar. A young John Morrissey took off his cap and said: “I can lick any man in the place.” (5)

This was soon put to the test, as eight men turned from the bar, grabbed chairs, bottles, and other handy makeshift weapons, and came at Morrissey determined to evaluate this confident boast. Nonetheless, Morrissey held his own, until Rynder hit him under the ear with a spittoon he found close by, to rescue him from the ensuing mayhem.

The Captain paid Morrissey’s medical bills and then employed him in the Tammany political operation as a “shoulder-hitter” (a fighter who enforced the will of a political boss by intimidation or violence).

Morrissey was also an emigrant runner. Working for Tammany Hall he would meet Irish immigrants at the dock, find them work and shelter, and after obtaining their pledges to vote for the Democratic Tammany ticket, he helped them obtain American citizenship. He did this by arranging their appearances before sympathetic and well-bribed judges. All he asked for in exchange was the family’s support of Tammany Hall-backed political candidates.

Morrissey continued his bare-knuckle fighting, and it was at one such bout that he would earn his lifelong nickname of ‘Old Smoke.’

During a fight in the basement of a New York hotel, a stove was overturned spilling hot coals over the floor. The fight continued until Morrissey’s opponent, violent street fighter Tom McCann, knocked John to the floor and held him down with his back upon the burning coals.

In agony, John’s flesh began to simmer and smoke. His friends came to his assistance, pouring cold water on the embers. Enduring the pain, Morrissey got back up to his feet, and in a blind rage, with his back still smoking, he battered McCann senseless. The watching enthralled bystanders gave him the nickname ‘Old Smoke,’ a name he was to be known by for the rest of his life. (6)

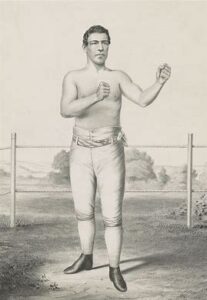

Bare Knuckle boxing champion of the world

Not yet 20, John Morrissey decided to leave New York and seek his fortune in the Californian gold rush. Despite finding no luck as a gold prospector, he turned his hand to gambling and was a remarkable success making a fortune winning gold from newly rich and usually drunk prospectors.

However, Morrissey could not escape the lure of the ring and he soon had his first professional fight, knocking out a well-known pugilist, George Thompson, in the 11th round and winning the then princely sum of $5,000. (7)

His pockets now full, Morrissey decided he would return to New York and challenge the current American boxing champion ‘Yankee Sullivan’ (a native of Bandon, Co Cork, whose real name was James Ambrose).

While waiting for Sullivan to agree to fight him, Morrissey continued his involvement in New York politics as an enforcer using his associates in the Dead Rabbits gang as additional muscle.

In 1853 Morrissey became bare knuckle boxing champion of the world.

The fight with ‘Yankee Sullivan’ was finally arranged for October 12th , 1853. Three thousand people gathered in a field in Boston Corner to witness a gruelling but engrossing and illegal bare-knuckle boxing match, with both Irish men fighting for the right to call themselves the undisputed champion of America.

Sullivan was the more technically gifted boxer and for 37 rounds he pummelled and battered Morrissey. He landed so many punches to his face that Old Smoke’s nose would never regain its original shape.

The bout soon began to take its toll and Morrissey was out on his feet and heading for defeat, but as had happened so many times in his short life, fate would turn in his favour.

As with many bare-knuckle bouts, the fighting was not just contained to the ring as a brawl broke out between the rival supporters and this began to spill into the ring. In the confusion, Sullivan didn’t hear the bell for the start of round 38 and he failed to leave his corner by the required time. The referee intervened, stopped the fight and awarded the bout to Morrissey. (8)

Battered, bruised and almost unconscious the confused Old Smoke was now the bare-knuckle champion of America. Morrissey proceeded to use his newfound fame and wealth to open a bar and gambling den, which would become famous for cock fights.

The battle between Old Smoke and Bill the Butcher

Unknown to John Morrisey, a notorious gang leader had lost a small fortune betting against him in his fight with Sullivan, this was William Poole, who had the well-earned nickname ‘Bill the Butcher,’ who was famously portrayed by Daniel Day-Lewis in the film Gangs of New York. Poole hated Morrisey from this moment on.

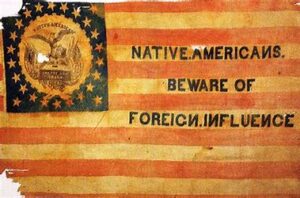

Bill Poole, a butcher by trade, was a former member of the Bowery Boys street gang, who now led his own gang fighting under the banner of the Native Americans. It was an alliance of the Washington Market Gang and the “Red Rover” Engine Company No. 34.

Bill Poole was known for his fierce and aggressive nature. He participated in several brawls and street fights, often getting into conflicts over political affiliations, as he was a supporter of the nativist political movement called the “Know-Nothing Party.”

In the 1850s Morrisey became embroiled in a violent rivalry with the anti-immigration ‘Know Nothing’ party and their street enforcer Bill ‘the Butcher’ Poole.

The Know Nothing Party was a political party that rose to prominence in the 1850’s. Its platform represented a strong stance on immigration, specifically targeting the anti-Catholic vote. The Know Nothings were fearful of the influx of German and especially Irish immigrants whom they regarded as hostile to American values and controlled by the Pope in Rome. They got their name when Members were asked about their nativist organisations and they replied, ‘I know nothing!’ (9)

Poole and his new gang were the muscle for the Know Nothings and were employed by Morrisey’s old Friend Captain Ryder who had left Tammany Hall to join the anti-immigrant faction. It was not long before Morrisey and Poole also a renowned boxer would come into direct conflict.

John Morrisey was now the undisputed leader of the Dead Rabbits gang and working again for Tammany Hall, Morrissey organised them to battle Bill the Butcher’s anti-immigrant ‘Know Nothing’ thugs. The two gangs became enforcers for battling political parties. The Know Nothing anti-immigration party employed William Poole and the Bowery Boys to ensure the ballot boxes gave the right results.

John Morrisey was now the undisputed leader of the Dead Rabbits gang and working again for Tammany Hall, Morrissey organised them to battle Bill the Butcher’s anti-immigrant ‘Know Nothing’ thugs. The two gangs became enforcers for battling political parties. The Know Nothing anti-immigration party employed William Poole and the Bowery Boys to ensure the ballot boxes gave the right results.

Morrisey and the Dead Rabbits were hired by the pro-Irish group, the Democratic Tammany Hall faction, to ensure Poole and his gang would not be successful and that Irish immigrants knew which party was looking after their interests.

In 1854, Poole and his men viciously attacked Morrissey and his fellow Dead Rabbits when they were defending the ballot boxes in favour of Tammany Hall mayoral candidate Fernando Wood.

Poole defeated Morrisey in a boxing match in 1854, suffering a broke rib.

Morrissey successfully saved the election from manipulation (Wood was victorious) and earned profound respect from Tammany Hall. But Bill the Butcher was angry, and his hatred for Morrissey went far beyond political rivalry and ethnic prejudice.

Later that year on July 27th, 1854, the feud between the two men came to a head. Angered at the constant harassment from Poole, Morrissey challenged him to a bare-knuckle boxing match, at the Amos Street dock.

This was billed as a fight Nativist versus Irish, Protestant versus Catholic; fight, it was a match-up of blood and pride for their gangs and peoples.

Morrisey, the larger man, was expected to win and at first was the clear winner, but Poole, who was the better boxer, took the upper hand when he flew a pulverizing rib punch to knock Morrissey to the ground. Poole gave him punch after punch while toppling Morrissey gouging his eyes and biting a part of his cheek off. Poole was victorious and Morrisey was defeated but not dead as his men dragged him from the dock to the hospital. (10)

As he recuperated, Morrisey swore revenge. Brutal Street fights between the two gangs continued, resulting in the deaths of several members.

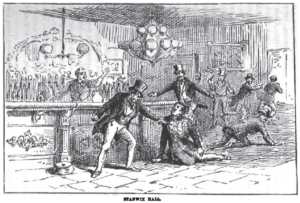

The Dead Rabbits would avenge their leader on the night of February 24th , 1855, when two of John Morrisey’s close allies, Lew Baker and Jim Turner deliberately got into a fight with Poole at the newly opened Stanwix Hall, opposite the Metropolitan Hotel on Broadway. (11)

While the argument raged Morrisey sat in a back room playing cards with another gang member. Welsh immigrant Lew Baker drew a pistol shooting Poole in the leg. Poole was taken away by his men and the wound turned gangrenous leading to his death two weeks later.

In February 1855 Poole was shot and fatally wounded following a bar brawl, on the orders of John Morrisey.

His last words were: “Good bye boys: I die a true American!”

Though the nativists in the city mourned Bill the Butcher, many of those he terrorized breathed a sigh of relief. Despite numerous requests, New York City refused to lower their flags to half-mast after Poole’s death.

Morrissey and Baker were charged with his murder, but they were released as the jury could not reach a verdict. This was hardly surprising as a sizeable proportion of them had been bribed not to.

Tammany Hall hero

It is no doubt Morrissey masterminded the death of Bill the Butcher and for his part in facing down Poole’s anti-Catholic and anti-immigrant party, the Know-Nothings, he achieved an almost mythical hero status within the local Irish community.

For his part in facing down Poole’s anti-Catholic and anti-immigrant party, the Know-Nothings, Morrisey achieved an almost mythical hero status within the local Irish community.

As a reward, the Democratic Tammany Hall faction gave Morrissey the go-ahead to open another gambling house, and also promised that there would be no police interference in the running of any of his operations.

With this blank cheque, Old Smoke retired from boxing to concentrate on his growing gambling and brothel empire.

Five years after his ‘defeat’ of Sullivan, Morrissey emerged from self-imposed retirement to fight John C. Heenan, the son of another Irish family in Troy.

Again, Morrissey’s ability to absorb punches allowed him to stay in the ring with a more skilled opponent and when Heenan lost the use of his right hand after hitting it off a corner stake, Old Smoke’s endurance paid off and he emerged victorious once more. (12)

Morrissey knew that despite his courage, he had been lucky in the ring and decided to retire and concentrate on his other skills, that of organised crime and gambling. He eventually owned 16 gambling dens and numerous brothels. Heenan claimed the title on Morrissey’s retirement from boxing in 1859.

Morrisey becomes respectable.

In 1861, he decided to reinvent himself once again and left New York behind to move to the then-small but growing town of Saratoga.

With $700,000 in cash, he underwent an image makeover, changing his ways to suit his new improved status and in the process, becoming a serious political force.

He built a new state-of-the-art and plush casino called the Club House, which counted Civil War generals like Sherman and Grant among its regular clients. (13)

He invested his money wisely and profitably in real estate and in 1863 opened the Saratoga Springs racing track which is still in use to this day.

In the 1860s Morrisey reinvented himself as successful businessman and later a Congressman

Always conscious of his past though, Morrissey kept his own name off all official documents when opening Saratoga Racecourse in 1864. He knew that his past would come back to haunt him and impact on the success of his new venture. He wisely appointed William Travers, a respected figure in the horse-breeding world, as the venue’s first president.

Saratoga racecourse is still thriving to this day, and it is Travers, not Morrissey, who is commemorated in its flagship race every August. (14)

Now a wealthy man and reinventing his life story, airbrushing his Dead Rabbit and brothel-owning past, Morrissey turned his eye towards politics. However, this time he would not be an enforcer but the candidate. His wealth and party machine would ensure he would be elected twice to the US congress as a Democratic member.

Despite his new found respectability, his temper was still fiery and old smoke once told a political opponent during a heated debate in the US House of Representatives

“I have been a wharf rat, chicken thief, prize fighter, gambler, and member of Congress and if any gentleman on the other side wants his constitution amended, just let him step into the Rotunda with me.” (15)

This was no ideal threat because as we shall see, John Morrissey was a man who rose from humble beginnings to the top of New York society and American politics using his fists and intellect in equal measure. However, that was a rare outburst, and his transformation became so complete that the writer Elliot J Gorn in his book, The Manly Art; Bare-knuckle Prize Fighting in America,’ said of him:

“As a politician, Morrissey maintained arms-length contact with the gangs, brothels, and saloons of his youth, and his rough personal manner had become quiet, even genteel.”

Morrisey turns on Tammany Hall

In early 1870, before revelations of Tammany Hall corruption became public, Morrissey joined a faction called the Young Democracy that revolted against Tammany Hall’s leader Boss Tweed’s authoritarian rule.

Tweed, however, learned of their plot to unseat him as head of Tammany Hall, and used policemen to prevent the Young Democracy members from entering the building on the night of their planned coup. The rebel organisation quickly folded, and Morrissey grew tired of the rampant corruption in Tammany Hall and left Congress after his second term.

Morrissey eventually testified against Boss Tweed and helped put him in prison. In 1875, now reinvigorated politically, Morrissey stood for a seat in the New York State legislature, beating his Tammany Hall opponent to win the right to represent Boss Tweed’s old district. Old Smoke had taken full revenge. (16)

His critics taunted him that he could only have been elected in such a safe precinct. A proud man, he then ran in 1877 and won in a new district, defeating another Tammany politician, August Schell.

In 1878, only a few months into his second legislative term, Morrissey contracted pneumonia and died on May 1, 1878, at the age of 47. Old Smoke was held in such high esteem that on the day of his funeral, the New York State closed all its public offices, and the flags were flown at half-mast.

On hi death in 1878, one newspaper wrote “That he had transcended his rowdy youth to become a useful citizen, a man of shrewdness, rectitude, and generosity.”

Twenty thousand mourners lined the streets to pay their last respects and the entire New York State Senate attended his funeral. He was buried in St. Peter’s Cemetery, just outside Troy. Not bad for a boy from Templemore, who used his wits and fists to rise from poverty to become a US Congressman.

Most newspapers praised the former pugilist, gambler, gang leader, brothel owner and politician on his death, with one report observing:

“That he had transcended his rowdy youth to become a useful citizen, a man of shrewdness, rectitude, and generosity.” (17)

In 1996 he was elected into the International Boxing Hall of Fame. This means the legend of John ‘Old Smoke ’ Morrissey, a boxer, the gang boss who ordered the death of Bill the Butcher and who was elected a US Congressman twice, lives on to this day.

John Joe McGinley October 2023

Sources

- www.timesunion.com

- New York Clipper. May 11, 1878.

- www.thefreelibrary.com/Irish+immigrants+and+the+rise+of+Tammany+hall

- (“Tammanyizing of a Civilization (1909) – Social Welfare History Project”)

- New York Clipper May 11, 1878

- New York Sun May 2, 1878. p. 1.

- Washington Evening Star October 3, 1926. p. 3.

- New York Clipper. October 15, 1853.

- Boissoneault, Lorraine. “How the 19th-Century Know Nothing Party Reshaped American Politics”. Smithsonian Magazine.January 13,2020.

- “Prize Fight in New York”. The Lancaster Ledger. Library of Congress. August 9, 1854. p. 2. Retrieved November 21,2018.

- “Terrible encounter of pugilists”. The New York herald. February 26, 1855. p. 1.

- “The Championship of America”. New York Clipper. October 30, 1858. p. 222

- “Losses of Gambling – A Caution”. Chicago Daily Tribune. Library of Congress. January 22, 1862. p. 1.

- Hotaling, Edward (1995). They’re Off!: Horse Racing at Saratoga. Syracuse University Press. pp. 41–50.

- “John Morrissey, the New York gambler”. Delaware Gazette. November 9, 1866.

- bioguide.congress.gov. US Congress.

- “The funeral of John Morrissey”. The Toledo Chronicle. May 9, 1878. p. 1.