When Donegal had trains! – The Londonderry and Lough Swilly Railway Company

By John Joe McGinley

The first railway in Ireland was planned in 1826 as a link between Limerick and Waterford.

However, planning was delayed and a railway line in Ireland would have to wait until 1834. This was the Dublin and Kingstown Railway (D&KR) between Westland Row in Dublin and Kingstown (Dún Laoghaire), a distance of 10 km (6 mi). By its peak in 1920, the Irish Rail Network covered 3,500 miles or 4,200km.

Donegal would be well served by the Railway in part due to its proximity with Derry. The first lines in the county opened in 1863. As the network grew, major towns in the county could be reached by rail, including Letterkenny, Burtonport and Glenties in the west of the county, and Killybegs and Ballyshannon in south Donegal.

On the Inishowen peninsula, a line went as far as Carndonagh. In the north of the county, services were run by the Londonderry and Lough Swilly Railway Company, usually called ‘The Swilly.’

The Londonderry and Lough Swilly Railway Company

The Londonderry and Lough Swilly Railway Company (The Swilly) was an Irish public transport and freight company that operated in parts of County Londonderry and County Donegal between 1853 and 2014.

It was Incorporated in June 1853, and once operated 99 miles of railway tracks. It began the transition to bus and road freight services in 1929. It closed its last railway line in July 1953 but continued to operate bus services under the name Lough Swilly Bus Company until April 2014. (1)

‘The Swilly’ became the oldest railway company established in the Victorian era to continue trading as a commercial concern into the 21st century.

‘The Swilly’ became the oldest railway company established in the Victorian era to continue trading as a commercial concern into the 21st century.

A small section of the network was originally broad gauge, but soon narrow gauge became the working norm across the county. The Donegal railways also ran to Derry city, which at one stage, had four railway stations. One in the docks area linked Derry with Letterkenny, Buncrana and the Inishowen peninsula, while the Victoria Road station on the east bank of the Foyle provided a connection to Killybegs.

The Donegal rail network was a marvel of Irish ingenuity and at 225 miles long, it was the longest narrow-gauge system in Ireland.

The County Donegal network survived until 1947 without any major closures. This was due to the General Manager from 1910 to 1943, Henry Forbes, who introduced many economies, not least of which was diesel railcar operation for most passenger trains. (2)

The station that serviced my local parish of Gweedore was an important part of the Donegal railway and had a short but interesting history.

Gweedore Station

In February of 1891, a commission was established to examine the merits of two proposals to connect Letterkenny to the isolated areas of the Donegal Northwest.

The commission heard evidence on two suggested routes:

- A direct line to Bunbeg via Churchill Creeslough, Dunfanaghy and Falcarragh

- A coastal route vie Ramelton, Milford, Carrigart, Dunfanaghy and Falcarragh

As a direct route would prove less costly and the Londonderry and Lough Swilly Railway Company were prepared to operate the route, this was given approval, but the exact route would need to be defined.

A great driver behind this decision was the need to bring greater prosperity to the Northwest. Government study of the area reported that in the neglected Northwest:

“There are two classes, namely the poor and the destitute. There are hardly any resident gentry; there are a few traders and officials; but nearly all the inhabitants are either poor or on the verge of poverty. The people are very helpful to one another, the poor mainly support the destitute” (3)

One of the measures instigated by the government was an attempt to open up the indigenous fishing industry to the markets of Derry, Belfast and Dublin. As part of this strategy Burtonport harbour was extended and up graded, all they needed now was a Rail link.

The Railways (Ireland) Act 1896 was a positive step forward as it provided funding for any company wishing to build a route. The decision was taken to build a line from Letterkenny to Burtonport operated by ‘The Swilly.’

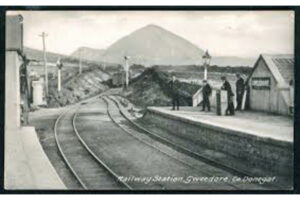

This was given Government approval on 10th February 1898. Gweedore station opened on 9th March 1903, when the Londonderry and Lough Swilly Railway opened their Letterkenny and Burtonport Extension Railway, from Letterkenny to Burtonport.

Gweedore station opened on 9th March 1903, when the Londonderry and Lough Swilly Railway opened their Letterkenny and Burtonport Extension Railway.

It brought tourism on a greater scale to the north west, with many people taking holidays in the Gweedore area and enjoying the relative luxury of the Gweedore Railway Hotel. Now the An Chúirt, Gweedore Court Hotel & Earagail Health Club. This was first built in the 1830s by Lord George Hill, who was a landowner in the area.

However, concern was raised by the Board of works that ‘The Swilly’ was neglecting its stations and an inspection tour was undertaken in in May 1917, by Joseph Tatlow from the Midland Great Westerns headquarters in Dublin.

On May the 7th, Tatlow delivered this damning indictment of the state of Gweedore Railway station:

“This station, being in the centre of an important tourist district and having adjacent a well-known hotel, frequented by a good class of tourists, would by any self-respecting railway company be kept in a clean and tidy and as far as possible attractive condition. I am sorry to say that the reverse is the case: it is dirty, slovenly, untidy and very deficient of paint.” (4)

Tatlow was not holding back, and he went on to report:

“The ladies’ waiting room is a disgrace. It has a concrete floor which looks rude and uncouth. Gweedore is a well enough constructed station and with ordinary care and attention could be kept quite attractive looking. The palings of the station are in bad order. The stationmaster’s office is on a lower level than the platform and his access to the latter is roundabout and awkward. The construction of a few steps to the platform would save him time and labour and be a great convince. The signal frame is on the platform and uncovered and frequently unworkable from frost and snow. It should be covered for protection and locked against interference when not in use.” (5)

The Tatlow report did not just deal with Gweedore, the entire Swilly operated line was dealt a devastating blow with issues raised with stations, rolling stock and employees.

No railway company in Ireland had ever received such a damning report and the chairman of the Swilly resigned with promises to rectify the issues Tatlow had outlined. The Gweedore station was refurbished as part of the response.

Impact of war and revolution on the railways

The First World War was also having an impact on the Swilly railway. One major impact was the reduction in the fishing stocks landed as men went to war and boats feared the U boats hunting the North Atlantic. Tourism also fell as the horrors of the Great War took hold.

In 1917 the entire Irish network was placed in the hands of a government committee.

The Donegal railway line would also witness civil unrest during the war years.

The first major event was on the 4th of January 1918 when 2 Nationalist Volunteers who had deserted from the British Army, James Duffy of Meenbanad, who had served in the Royal Dublin Fusiliers and James Ward of Cloughlass, who had served in the Royal Inniskilling Fusiliers, were arrested and held awaiting transfer to Derry.

The railways in Donegal were severely disrupted by the First World War and then the Irish revolution between 1914 and 1923.

A 4-man armed escort arrived in Burtonport, ready to take the men for trial in Derry. They spent the day in a local hostelry and were drunk when the train departed. It was soon stopped by a rescue party, supported by a large crowd of locals, who quickly disarmed the drunken escort and freed the prisoners. (6)

This act is recognised as one of the first actions of the War of Independence that would soon set Ireland alight.

On May Day 1918 employees at Gweedore station joined with their colleagues in the Swilly and stopped work as part of the national protest against conscription.

During the War of Independence, IRA activity in Donegal was stepped up and attacks against the railway network in Donegal increased. This was to isolate the Crown forces and to deny them supplies of food and ammunition. It was also to ensure captured volunteers were rescued as soon as possible.

From July 1920, Gweedore station staff, in common with their colleagues in ‘The Swilly’ refused to have anything to do with military transports or even civilian trains with Crown forces on-board! This was to be called the ‘Munition’s strike.’

The Burtonport line, including Gweedore was effectively shut down as train crew’s feared Volunteer retaliation if they kept working.

On April 25th, 1921, Gweedore station was entered by the IRA and goods from Belfast were destroyed. The telegraph lines at Crolly and Falcarragh were also cut.

Hostilities were paused with Truce of July 11th, 1921. On the 13th of July 1921, the IRA GHQ in Dublin issued orders of all closed railways including the Swilly to reopen for traffic. When the truce was signed, train, services resumed to Letterkenny but Gweedore station and the Burtonport line did not reopen until 25th July.

The Civil War saw further unrest on the Donegal railway. Donegal also found itself isolated by the partition of Ireland.

Firstly, Donegal became the site of an undeclared ‘border war’ along the new frontier, where both pro and anti-Treaty IRA units launched attacks over the new border into Northern Ireland in the first half of 1922.

The railways were now under attack and on March 31st, 1922, the Derry to Burtonport train was attacked at Newtoncunningham and copies of the Derry journal burnt. The paper sent more copies only for these to be intercepted and burnt. The campaign was aimed at food merchandise and newspapers from the North that were all destroyed when found on trains.

This was in part a response to the expulsions of mainly Catholic workers from the Belfast shipyards and other places of work during the ongoing sectarian violence in the north during the summer of 1920.

The anti-Catholic ‘pogroms’ in Belfast were the catalysts that resulted in what would become known as the Belfast Boycott, which had first been applied in August 1920 by Dáil Éireann, forbidding doing business with Belfast while violence against Catholics and nationalist continued there. It was lifted after the Anglo Irish Treaty by Michael Collins’ Provisional government but re-imposed by the anti-Treaty IRA in early 1922. (7)

Within months, there were many incidents of “unauthorised persons” enforcing the boycott, causing the government to issue a warning that “the demands referred to are made without lawful authority.” (8)

Some of this activity was conducted along the route of the Donegal Railway.

Such was the intensity of the disruptions that on April 29th, 1922, the Swilly announced that they could no longer guarantee a reliable service and they refused to accept any further responsibility for any losses from disturbances.

As the Civil War erupted in June 1922 the uncertainty on the Donegal railway continued. On July 1st, the National Army pro-Treaty forces commandeered a train from Buncrana and moved into the Inishowen Peninsula. Clonmany was captured without incident. Pro Treaty troops then moved onto Carndonagh, where Anti Treaty forces had fortified the workhouse.

A gun battle broke out but after the National Army opened fire with a machine gun the anti-Treaty forces surrendered. (9)

Because of the ongoing turmoil of the Civil War and the disjointed service of the rail service, in early 1923 locals in Gweedore and the Rosses met in Dungloe where inhabitants and merchants voiced their lack of confidence in the Londonderry and Lough Swilly Company and called on the fledgling Irish Government to transfer the Letterkenny to Burtonport line to the Strabane and Letterkenny Railway Company.

This request was refused, and things only got worse for the Swilly when border customs posts where introduced on the line in April 1923.

This led to an increase in smuggling as many people crossed the Border to purchase goods that were unobtainable in Donegal.

Engine drivers were coaxed – or maybe even bribed – to slow down near railway crossings where goods could be dropped off at the side of the line and quietly collected later by their owner. It was common practice for ladies to wrap lengths of fabric, or even the odd blanket, round themselves under a concealing winter coat.

One lady, when asked what was under her coat replied coyly, ‘I’ll tell you in six months,’ (10)

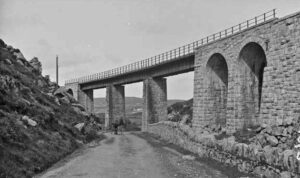

Owencarrow Viaduct disaster

Tragedy was to strike the Donegal line on the night of 30 January 1925 at around 8pm at the Owencarrow Viaduct, outside Kilmacrennan.

On that evening, an engine pulling two carriages, one wagon, and a combined van, was travelling on the Londonderry and Lough Swilly Railway Burtonport Extension.

The 14 passengers had been enjoying the journey, having left Kilmacrennan Station at 7:52 pm, running only 5 minutes late.

It was a wild and stormy night and at around 8pm the train approached the Owencarrow Viaduct which was considered by the drivers as dangerous in bad weather. However, the driver later reported that he did not see anything unusual.

Tragedy was to strike the Donegal line on the night of 30 January 1925. Four passengers were killed and five seriously injured when the train derailed on the Owencarrow viaduct.

Travelling at 10 miles an hour the train entered the viaduct, which was nearly 440 yards in length. When the train was a little more than 60 yards onto the viaduct, there was a great gust of wind, which lifted the carriage next to the engine off the rails.

The driver applied the vacuum brake and stopped the train. When the train came to a halt, the back carriage, which had been lifted off, had carried the wagons halfway over the wall of the bridge. The other carriage was lying over the embankment, its roof torn off throwing 4 passengers to their deaths, with five others seriously injured. One passenger a Miss Campbell had a lucky escape. She was flung from the upturned carriage, landing on soft and boggy soil, sinking knee-deep into it. (11)

The subsequent inquest cleared the Driver and blamed the accident on the decaying state of the line, it was obvious ‘The Swilly’ had not learned the lessons of the Tallow report.

You can see the remains of the Viaduct If you take the N56 from Creeslough heading to Letterkenny,

The end of the line

The ‘Emergency’ as World War II was called in Ireland, proved a great strain on the Donegal railway network.

In May 1940 ‘The Swilly’ announced that from the 3rd of June 1940 as a result of a government statutory order, the Letterkenny to Burtonport line was to be closed and the lines dug up.

The reasons given for the closure were a decline in traffic and the prohibitive costs of the repairs needed on the network.

While the odd goods train still travelled to Burtonport, the end was coming and in August 1940 the firm of George Cohen and company were employed to start digging up the railway tracks from the Burtonport end.

Dismayed and angry at the removal of their rail network, the people of Northwest Donegal protested at the closure. On the 18th of November 1940, 100 men gathered at Crolly to block the demolition work of the Cohen Company.

Though there was an order to close the rail line in Donegal and take up the tracks in 1940, it was blocked due to public pressure and remained open until 1949

The Garda and a local TD calmed the crowd by promising that the government would review the decision to close the line and that demolition would be temporarily halted. This was to prove only a short reprieve, because on the 29th of November, the decision to close the line was upheld.

However, by now with oil and petrol rationing in full flow, travel by road was no alternative to rail and ‘The Swilly’ decided to halt the demolition of the remainder of the line and permission was sought to reopen the Letterkenny to Gweedore line.

On the 14th of January 1941, a goods train left Letterkenny for Gweedore returning with a consignment of Herring for the Belfast market. This proved that the line whilst in disrepair was passable. A decision was taken that a dilapidated line was better than no line at all.

Services began again on the 3rd of February 1941 when the Letterkenny to Gweedore line reopened for freight traffic. From March 1943 passengers were also allowed to officially travel the route. Many had done so unofficially from 1941 onwards!

By the end of the war years, the company was carrying nearly 500,000 passengers per annum on its rail services from Derry to Buncranna and Gweedore.

With the ending of hostilities and the restoration of petrol and oil supplies, the company re-embarked on its policy of replacing rail services by road transport as vehicles became available and more economically viable.

As the Emergency ended, the line from Letterkenny to Gweedore was in a dangerous state of disrepair. The daily goods service between Letterkenny and Gweedore was withdrawn in January 1947. However, a few special trains operated until June of that year when the line finally closed. The removal of the tracks and rolling stock began in 1949. (12)

The rest of ‘The Swilly’ line would limp on for just a few more years. The last train to run on ‘The Swilly’ line was the 2.15 pm from Letterkenny to Derry on 8th August 1953. It included 14 wagons of cattle and arrived 50 minutes late.

Bob Turner was the driver with Paddy Clifford as fireman. The Derry Journal reported at the time “The guard, Mr. Daniel McFeeley, or anyone else, did not call out ‘Next Stop Derry’. Everyone knew that the next stop would be the last stop – the last ever.” (13)

Lifting of the lines commenced almost immediately and was completed in early 1954.

The last train to run on ‘The Swilly’ line was the 2.15 pm from Letterkenny to Derry on 8th August 1953. It included 14 wagons of cattle and arrived 50 minutes late.

The rail network in the north also suffered a blow when the Sligo, Leitrim and Northern Counties Railway closed on 1st October 1957.

The Great Northern Railway of Ireland closed its railway station in Enniskillen on the direct orders of the Government of Northern Ireland. This left a vast swathe of Northern Ireland and the Republic without rail transport. (14)

Such was the attachment to the Donegal railways that after the line from Donegal town to Ballyshannon closed down in 1959, two of the railway workers continued to operate a freight service between the two towns for a month before the bosses in Dublin realised what was happening.

The loss of such an important infrastructure asset as the railways in Donegal and the North West resulted unquestionably in the adverse effect to the county’s economic development.

Donegal is quite geographically isolated and economically under-developed. The dismantling of railways exacerbated those problems, with which Donegal is still grappling today.

The loss of such an important infrastructure asset as the railways in Donegal and the North West resulted unquestionably in the adverse effect to the county’s economic development.

The absence of the train is still felt by people in Donegal, where travelling between towns or to other parts of the island on public transport usually means using a car to reach a bus stop or the airport, and often requires using two or more services to get to a final destination.

In modern day Ireland intercity rail passenger services operate between Dublin and Belfast, Sligo, Ballina, Westport, Galway, Limerick, Ennis, Tralee, Cork, Waterford and Rosslare. With further regional service between Galway and Limerick and around the Dublin area.

However, no trains operate in Donegal, one of Ireland’s largest counties. The forgotten Donegal and Gweedore station is no more.

Sources:

- Donegal Now 18th April 2014

- History – Donegal Railway Restoration CLG

- History Ireland 18th-19th Century Social Perspectives: Issue 2 (Mar/Apr 2005)

- Joseph Tatlow, Fifty years of Railway Life in England, Scotland and Ireland, Chapter 20

- Tatlow, Fifty Years of Railway Life in England, Scotland and Ireland, Chapter 20

- Liam O Duibhir ,TheDonegal Awakening – War Of Mercier Press Pages 60. 61

- Angelo Celt Sun 22 Aug 2021

- Angelo Celt Sun 22 Aug 2021

- Kieran Glennon ,From Pogrom to civil war : Tom Glennon and the Belfast IRA:, (2013) Page 205

- Irish times Sep 25, 2017

- monreaghulsterscotscentre.com

- History – Donegal Railway Restoration CLG

- Derry Journal August 1954

- Irish times Sep 25, 2017

Owencarrow Viaduct Casualties

The deceased:

- Mr. Philip Boyle, Leabgarrow, Arranmore

- Mrs. Sarah Boyle, Leabgarrow, Arranmore (wife of Philip)

- Neil Duggan, Meenabunone

- Mrs. Una Mulligan, Falcarragh.

Five others were seriously injured:

- Mrs. Brennan, Dungloe – severe injuries to her head

- Mrs. McFadden, sister-in-law of Mrs. Brennan – shock

- Mrs. Bella McFadden, Gweedore – shock

- Edward McFadden, Magheraroarty – shock and wounded hand

- Denis McFadden, Cashel, Creeslough – severe concussion.