Wikipedia, the Black and Tans, and the ‘R.I.C. Special Reserve’

By David Leeson

Who were the Black and Tans?

According to Wikipedia: ‘The Black and Tans (Irish: Dúchrónaigh) were constables recruited into the Royal Irish Constabulary (R.I.C.) as reinforcements during the Irish War of Independence. Recruitment began in Great Britain in January 1920 and about 10,000 men enlisted during the conflict. The vast majority were unemployed former British soldiers from Britain who had fought in the First World War.’

That is a good definition—but if you keep reading, you will find something odd. Later in its introduction, the article notes that, ‘Some sources say the Black and Tans were officially named the “R.I.C. Special Reserve,” but this is denied by other sources, which say they were not a separate force but “recruits to the regular R.I.C.” and “enlisted as regular constabulary.”

Many misconceptions about the Black Tans, especially terming them ‘Special Reserve’ can be traced back to the Wikipedia article on the subject.

Indeed—if you had searched for this article before 5 January 2020, you would have read something completely different. According to this earlier version, ‘The Black and Tans (Irish: Dúchrónaigh), officially the Royal Irish Constabulary Special Reserve, was [sic] a force of temporary constables recruited to assist the Royal Irish Constabulary (R.I.C.) during the Irish War of Independence.’[1]

To borrow a phrase from H. L. Mencken: that description was clear, simple, and wrong. The Black and Tans were not ‘officially the Royal Irish Constabulary Special Reserve.’ The Royal Irish Constabulary did not have a ‘special reserve.’

To make matters worse, the Black and Tans were not a ‘force of temporary constables.’ They were not a separate force, and they were not temporary constables. The article then went on to say that this phantom force—the ‘R.I.C. Special Reserve’—was ‘the brainchild of Winston Churchill, then British Secretary of State for War,’ which was also wrong: the Black and Tans were the brainchild of Walter Long, then First Lord of the Admiralty.[2]

What is more: if you dig down through this article’s earlier versions, by following the ‘View History’ link at the top of the page, you will discover that it was always wrong, right from the start. For about eighteen years, between January 2002 and January 2020, Wikipedia promoted various misconceptions about the Black and Tans—describing them in different ways and assigning them different names—before finally settling on the ‘Royal Irish Constabulary Special Reserve’ in 2015.

None of these descriptions or appellations was correct, but their appearance on Wikipedia lent them a spurious authority: in a couple of cases, these misconceptions about the Black and Tans even appeared in other publications, which Wikipedians then cited in support of their misconceptions. But historians must share some of the blame here, as well.

I have traced Wikipedia’s references to a ‘Special Reserve’ back to the work of an amateur scholar that was published in 2010. This work has been cited with confidence by both popular and academic histories, but when I checked, I could not find any references to an RIC Special Reserve anywhere, in any document, published or unpublished, before that date.

Who the Black and Tans Were

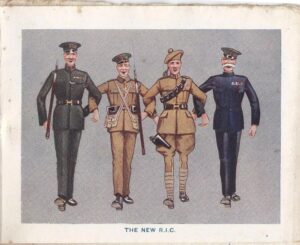

(Picture: RTE Archives, reproduced by agreement with David Leeson for this article only)

The Black and Tans were mostly British ex-servicemen who joined the Royal Irish Constabulary to work as militarized police during the Irish War of Independence.[3] That is to say:

- The Black and Tans were mostly British. Indeed—aside from the mixed uniforms they wore at first, their Britishness was their most distinctive characteristic. The Royal Irish Constabulary had always been a force of Irish police, recruited in Ireland. At the beginning of 1920, however, District Inspector Major Cyril Fleming of the R.I.C. set up shop in London, at the Army Recruiting Office on Great Scotland Yard, off Whitehall, and began recruiting constables in Great Britain. While a few of the men who then applied for these positions came from Ireland or overseas, most of them were British. In April 1920, for example, Major Fleming recruited ninety-seven constables: four came from outside the United Kingdom, nine came from Ireland, and eighty-four came from Great Britain.[4]

In the beginning, Irish police recruits outnumbered British police recruits: in April 1920, for example, in addition to the 97 British recruits mentioned above, 273 Irish recruits joined the R.I.C. in Ireland.[5] But the number of British recruits rose in the summer, while the number of Irish recruits fell. Then, in the autumn, British recruiting surged, and while it fell off somewhat thereafter, it remained high until the Truce.

The Black and Tans were mostly British ex-servicemen who joined the Royal Irish Constabulary to work as militarized police during the War of Independence

As a result, in its General Annual Report for 1921, the War Office complained that, ‘The necessity for recruiting large numbers of men for service in the Royal Irish Constabulary, in which body the conditions as to pay, etc., were more attractive than in the Army, has also deprived the Regular Army of a number of men who in all probability would otherwise have enlisted therein.’[6]

- These British police recruits were mostly ex-servicemen. The Royal Irish Constabulary was the British regime’s first line of defence in Ireland, but its armed and uniformed constables were not as formidable as they looked. Their military effectiveness and military efficiency (that is to say, their willingness and ability to fight an irregular war) were both limited, and by the fall of 1919 their numbers were declining.[7] They were increasingly shunned and isolated, and the insurgent Irish Republican Army’s attacks on them were becoming bolder, more frequent, and more violent: as a consequence, police morale was falling, and the number of resignations and retirements from the force was rising.

The Black and Tans—British recruits for the Royal Irish Constabulary—were one of the British government’s responses to this revolutionary situation. In addition to providing replacements for those Irish constables who had resigned and retired, it was hoped that the military training and war experience of British ex-servicemen would prepare them to deal with Irish republican guerrillas.

Recruiting advertisements made it clear that discharged soldiers were wanted, and out of the 270 British recruits who joined the force in July 1920, for example, 242 (90 per cent of them) were ex-soldiers. Of the remainder, nineteen were ex-sailors, two were ex-marines, one was an ex-army officer, one had been a member of the Officer’s Training Corps, and one had served in the Volunteer Training Corps. Only four of these British recruits had no military service experience at all (and one of these four civilians was an ex-policeman).[8]

- These British ex-servicemen joined the Royal Irish Constabulary—and this, for some reason, is the point that has given Wikipedians the greatest difficulty. Despite their British backgrounds, and their military training and experience, the Black and Tans were appointed as permanent constables of the Royal Irish Constabulary, working with other (Irish) constables as part of that force. They were not members of the temporary forces—the temporary cadets of the Auxiliary Division and the temporary constables of the Veterans Division. Nor were they special constables, unlike the members of the Ulster Special Constabulary.

There was, admittedly, a great deal of confusion surrounding the Black and Tans, even at the time. Among other things, their (lack of) uniforms helped foster the mistaken impression that the new British recruits constituted a separate force: some had only caps and belts to mark them as policemen, while others wore military tunics with police trousers, or vice versa.[9] They were nicknamed ‘Black and Tans’ after a pack of foxhounds in county Limerick, and the name stuck, even after they were given proper police uniforms.[10]

The Black and Tans were not temporary constables, or a reserve or, unlike the Auxiliary Division, a separate unit, but recruits to the Royal Irish Constabulary.

In addition, most British recruits received their (very limited) police training at a sub-depot, Gormanston Camp—a converted aerodrome in county Meath, instead of at the R.I.C. Depot in Phoenix Park, Dublin.[11] As a result, the Chief Secretary for Ireland, Sir Hamar Greenwood, felt compelled to clarify their status in the House of Commons on 25 October 1920:

The men described as Black and Tans are not a separate force, but are recruits to the permanent establishment of the Royal Irish Constabulary. The large majority are ex-service men recruited in Great Britain. Their terms of service and rates of pay as members of the Royal Irish Constabulary are similar to those of the police forces of Great Britain, and are based on the recommendations of the Desborough Committee.[12]

Who the Black and Tans Weren’t

Now that we’ve reviewed who the Black and Tans were, let’s go through the various definitions that Wikipedia’s editors have offered, in chronological order.

2002: ‘A special auxiliary force of the Royal Irish Constabulary’[13]

The Black and Tans were not ‘a special auxiliary force.’ This confuses the Black and Tans with the Auxiliary Division of the Royal Irish Constabulary (A.D.R.I.C.)—a distinctive new force that was created in July 1920.[14] Unfortunately, the Auxiliaries were (and are) also sometimes called ‘Black and Tans.’

In the words of one R.I.C. veteran: ‘They formed a new corps [the Auxiliaries] and some people called them the Black and Tans. They were dressed in army uniform. They weren’t Black and Tans in the proper sense of the word.’[15]

In particular, most photographs of ‘Black and Tans’ are photographs of Auxiliaries. Indeed—at the time of writing, Wikipedia’s article on the Black and Tans is illustrated with a picture of an Auxiliary smoking and carrying a Lewis gun.[16]

2004: ‘The Royal Irish Constabulary Reserve Force’[17]

The Black and Tans were not ‘the Royal Irish Constabulary Reserve Force.’ The R.I.C. did have a Reserve, but it was a small force of just a few hundred constables, ‘based at the Phoenix Park depot, but capable of being deployed to any part of the country where extra men were urgently required.’[18] (One man who was part of the Reserve later remembered that ‘you were rushed to every place that was in trouble.’)[19]

And if we check the nominal return for this force, dated 3 March 1921, we will discover that it consisted of just 10 head constables, 54 sergeants, and 201 constables—of whom just 11 were Black and Tans.[20]

2009: ‘One of two newly recruited bodies’ ‘employed by the Royal Irish Constabulary’[21]

The Black and Tans were not ‘one of two newly recruited bodies.’ This is close to being correct: the Black and Tans were newly-recruited—but they were not a body; they were part of the wider body of permanent constables.

Officially there were three newly recruited bodies of police in Ireland during the War of Independence: the Auxiliary Division, R.I.C.; the Veterans Division, R.I.C. (about which more soon); and the Special Constabulary, which is generally known as the Ulster Special Constabulary or U.S.C. (about which more later). The Black and Tans were none of these.

2010: ‘Temporary Constables’[22]

(Courtesy of PSNI Police Museum)

The Black and Tans were not ‘temporary constables.’ The British Government did recruit over two thousand temporary constables to assist the Royal Irish Constabulary and its Auxiliary Division, but these were not front-line police: instead, they were recruited ‘for the purpose of taking over orderly, fatigue, and similar duties.’[23]

These were sometimes called ‘Section B men’ or simply ‘B men.’ In 1960, for example, a former constable who had worked at the R.I.C. recruiting office in London, assisting the Army doctor who gave medical examinations to recruits, described how the doctor ‘was examining a heavy and florid candidate for section B (cooks and orderlies who must be ex regular soldiers).’[24]

Some of these temporary constables were formed into a separate Veterans Division, to assist the Auxiliary Division, and as this name implies, they were older men: most of the temporary constables who joined the R.I.C. in October 1920 were at least 40 years old.[25] Thus, they more closely resembled commissionaires than police constables.

These temporary constables do pop up from time to time in the historical record: in his testimony to the Court of Inquiry into the Burning of Cork, for example, the second-in-command and adjutant of K Company, A.D.R.I.C. tried to throw suspicion on the sixteen temporary constables who had been assigned to work with his temporary cadets. ‘The Temp. Constables are not a good stamp of man and unless closely watched and [sic] unreliable,’ he complained.[26] But for the most part, the R.I.C.’s temporary constables remained in the background of the War of Independence.[27]

March 2012: ‘One of two ad hoc paramilitary units’[28]

The Black and Tans were not ‘one of two ad hoc paramilitary units.’ This is partly correct: the Black and Tans were one of Dublin Castle’s ad hoc responses to the declining effectiveness and limited efficiency of the Royal Irish Constabulary.

They were not a ‘paramilitary unit,’ (that is; a military-style formation that is not part of the formal military) however, and to describe them that way confuses them, once again, with the Auxiliary Division. Interestingly, the A.D.R.I.C.—a truly paramilitary unit—was an ad hoc response to the seeming failure of this earlier ad hoc response.

The chief of the British police forces in Ireland, Major-General Tudor, justified the creation of the Auxiliary Division in July 1920 by claiming that recruiting in Great Britain was not enough to restore the strength of the R.I.C. ‘It is essential to reinforce the Royal Irish Constabulary quickly,’ he wrote. ‘Recruiting in the ordinary way will take time.’[29]

But this was too pessimistic: more than five thousand ex-soldiers joined the R.I.C. in the autumn and winter of 1920-21, as permanent constables, while only about two thousand ex-officers ever joined the A.D.R.I.C. as temporary cadets.[30]

December 2012: ‘Temporary Constables’ (Again)[31]

For the first time, this version of the article provides a source to support its claims: Devlin Kostal, ‘British Military Intelligence-Law Enforcement Integration in the Irish War of Independence, 1919-21,’ in Can’t We All Just Get Along? Improving the Law Enforcement-Intelligence Community Relationship (Washington, D.C.: National Defence Intelligence College Press, 2007). Captain Kostal is a United States Air Force officer, and he based his article in this edited collection on his Master’s thesis on the same topic.[32]

Unfortunately, while Kostal says a number of interesting things about the integration of military intelligence and law enforcement, his chapter is full of mistakes on matters of detail. ‘In March 1920,’ he says, for example, ‘the R.I.C. was augmented by the Royal Irish Constabulary Reserve Force, the now-infamous “Black and Tans.”’ [33]

The strange thing here, however, is that Kostal does not actually refer to the Black and Tans as temporary constables. (Remember that Kostal’s chapter is adduced to show that they were temporary constables—not that they were the ‘Reserve Force.’)

Since his own chapter was published in 2007, when Wikipedia was claiming that the Black and Tans were the Reserve Force; and since this chapter includes images taken from Wikipedia, it seems likely that Kostal got this information about the Reserve Force from Wikipedia: and that, as a result, by this point, Wikipedia’s article on the ‘Black and Tans’ was effectively citing a previous version of itself, in support of its claims.[34]

January 2015: The ‘Royal Irish Constabulary Reserve Force’ (Again)[35]

At this point, we might expect Wikipedia to go back to calling the Black and Tans the ‘Reserve Force,’ while citing Kostal’s chapter as its authority for this reversion. Instead of doing that, however, Wikipedia drops its reference to Kostal’s chapter, and cites a completely different source: a leader from the Guardian newspaper, published in May 1921 during the Anglo-Irish treaty negotiations, and subsequently republished online as part of the Guardian’s ‘From the archive’ series. This source states:

Mr. Churchill has signalised himself quite recently with foolish talk about the “real war” that is to follow should the present negotiations fail, in contrast to the “mere bushranging” represented by the glorious achievements of our Black-and-Tans. [The Royal Irish Constabulary Reserve Force of 7,000 men, a byword for brutality][36]

The problem here will be clear to any trained historian. The reference to the ‘Royal Irish Constabulary Reserve Force’ was not part of the original article: instead, it was interpolated into the text by an editor; that’s why it’s enclosed in brackets. Since this unknown editor does not cite any sources, it seems likely that they got this information from Wikipedia: and that, once again, by citing this source, Wikipedia’s article on the ‘Black and Tans’ was effectively citing itself.

December 2015: The ‘Royal Irish Constabulary Special Reserve’[37]

Finally, the Black and Tans were not ‘the Royal Irish Constabulary Special Reserve.’ At first glance, there seems to be no reason to doubt what Wikipedia says here. This version of the article was edited by ‘Asarlaí,’ an Irish Wikipedian whose main interest is the history, mythology, and geography of Ireland. He is a senior editor, and his user page lists many articles to which he has made major contributions.

His edits are well-researched, well-written, and well-documented—and in this case, he cites two seemingly reliable sources: the first is a published article in Ireland’s most popular history magazine, History Ireland, and the second is a doctoral dissertation (subsequently revised for publication by the Collins Press, Dublin).[38] If we can’t trust these two sources, who can we trust?

The problem, as I have written of late, is that I cannot find any primary source that refers to the Black and Tans this way. In my own research, I have examined thousands of pages of documents in the Home Office, Colonial Office, and War Office collections at the National Archives of the United Kingdom.

In addition, I have reviewed letters preserved at the archives of Trinity College, Dublin, from Royal Irish Constabulary officers who were personally involved in recruiting and training Black and Tans. In all that time, I do not recall ever seeing any reference to an ‘R.I.C. Special Reserve’ or ‘R.I.C.S.R.’ in any document, official or unofficial.

To the best of my knowledge, no such separate formation ever existed, and no one ever called the Black and Tans a ‘special reserve.’. To the best of my recollection, every document I have ever examined has referred to the Black and Tans just as British recruits and constables in the Royal Irish Constabulary.[39]

In Search of the R.I.C. Special Reserve

This is not conclusive, of course, because like any historian, I make mistakes. On pages 200-2 of my book on the Black and Tans and Auxiliaries, for example, I discuss the case of ‘Temporary Constable John Reive.’ Reive was dismissed from the Force on 22 December 1920 after he was arrested for murder and armed robbery, and subsequently pleaded for clemency from prison, on the grounds that he was committing a reprisal, not a robbery.[40]

While I was researching this article, I discovered that Reive was not a temporary constable at all: he was a permanent constable, who had joined the Force on 13 October 1920. This meant that Reive was part of the cluster sample that I had studied closely (but not closely enough, it seems) to learn more about the Black and Tans.[41]

It seems that references to the RIC ‘Special Reserve’ in fact refer to the Ulster Special Constabulary.

It was therefore possible that I missed those documents that refer to the Royal Irish Constabulary Special Reserve: but that seemed like a rather large oversight, even for me. For this reason, while researching this article, I reached out to the person who seemed like the source of Wikipedia’s information about the R.I.C. Special Reserve: John Reynolds, author of 46 Men Dead: The Royal Irish Constabulary in County Tipperary, 1919-22.

In this book, which is a revised version of his doctoral dissertation, Reynolds describes the Black and Tans as the Royal Irish Constabulary Special Reserve, but he does not provide an authority for this reference.[42] So I asked him if he could shed any light on this question.[43]

In our correspondence, Reynolds pointed out that Ernest McCall refers to the Black and Tans as the Royal Irish Constabulary Special Reserve in his book The Auxiliaries: Tudor’s Toughs.[44] More importantly, after conferring with R.I.C. historian and police genealogist Jim Herlihy, Reynolds referred me to a brief general history of the R.I.C. which has been archived in the British Home Office papers, and which says:

At various dates since July 1920, the following Auxiliary Forces were formed, and their expenses borne by the Vote for R.I.C., viz.:–

Auxiliary Division

Veterans Do.

Special Constabulary[45]

In my reply to Reynolds, however, I pointed out that the Black and Tans could not be the ‘Special Constabulary’ mentioned in that document. The document itself refers to Auxiliary Forces formed at various dates since July 1920—when, as we know, the Black and Tans began joining the R.I.C. in January 1920.

The Special Constabulary referred to in the document, I said, must be the Ulster Special Constabulary. The organization of this force was announced at the end of October 1920.[46] It was at first called simply the ‘Special Constabulary’: it only became known as the Ulster Special Constabulary later.[47]

What is more: the Ulster Special Constabulary was divided into three classes: ‘the A Specials, who were to be whole time; the B Specials part-time and the C Specials listed as available for use in an emergency.’ [48] The document quoted above includes a Schedule of Allowances for the Special Constabulary: this provides boot, rent, and separation allowances for Class A, while for Class B, it provides only a semi-annual allowance ‘to cover wear and tear of private clothes,’ along with a ration allowance ‘for each attendance exceeding one week exclusive of training drills.’[49]

Clearly, these are allowances for full time, uniformed special constables (Class A) on the one hand, and part-time special constables (Class B) on the other. Hezlet even says of the B Specials that, ‘They were unpaid but were given an allowance to cover wear and tear of their clothes. At first they had no uniform but were issued with caps and armlets.’[50] By contrast, there were no part-time Black and Tans: they were all full-time constables who were stationed in barracks with their Irish comrades. The document in question can only be referring to the Ulster Specials.

The Source of a Misconception

I have not been able to contact Ernest McCall. On p. 26 of his book The Auxiliaries: Tudor’s Toughs, at the head of a section on the ‘R.I.C. Reserve Force,’ McCall says:

Many commentators on the period have called the Auxiliary Division R.I.C. the R.I.C.’s reserve force. This was not and never was the case, the R.I.C. and its predecessor the Irish Constabulary had a reserve force since 1839. This was a result of an Act of Parliament many years before the Irish War of Independence and the formation of the Auxiliary Division.

So far, so good: that is quite correct.[51] But McCall then goes on to say:

However, the official name of the Black and Tans was the Royal Irish Constabulary Special Reserve (R.I.C.S.R.) and this may be were [sic] writers and commentators on the period may have become confused. Like the A.D.R.I.C., the R.I.C.S.R. should not be confused with the R.I.C. Reserve Force.[52]

McCall does not provide an authority for this claim, but he does make the mistake of referring to the Black and Tans as Temporary Constables on p. 37 and p. 39. And to make matters worse, he then goes on to garble both a quotation from, and a reference to, the verbal answer by Chief Secretary Greenwood from 25 October 1920, referenced above.[53] Clearly, whatever the merits of his research on the Auxiliary Division, McCall’s book is not a reliable source of information about the Black and Tans.

Conclusion

Until January 2020, Wikipedia’s article on the Black and Tans opened with a number of outright factual errors which had passed unchallenged for years:

Until January 2020, Wikipedia’s article on the Black and Tans opened with a number of outright factual errors which had passed unchallenged for years: and a review of its history has revealed that these were just the latest in a procession of errors that stretched back to this article’s creation.[54] But the blame is not theirs alone. Since 2015, Wikipedians have been doing better—but both popular and academic historians have let them down, by making mistakes of their own.

There is no reason for this: the Royal Irish Constabulary’s official records have been open to researchers for decades, and many of these records are now freely available online. So those of us who are without sin—let us cast the first stone. If there is a lesson to be learned here, it’s that we all need to watch what we say and check our sources more closely. In history, accuracy is a duty, not a virtue.

David Leeson is a Professor of History at Laurentian University, Canada. He is a scholar of British policing in Ireland and is the author of ‘The Black and Tans, British Police and Auxiliaries in the Irish War of Independence’ (2011).

If you enjoy the Irish Story and wish to support our work, please considering contributing at our Patreon page here.

References

[1] ‘Black and Tans,’ in Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Black_and_Tans (accessed 21 July 2021).

[2] Charles Townshend, The British Campaign in Ireland 1919-1921: The Development of Political and Military Policies (Oxford, 1975), pp. 30, 44-6; Eunan O’Halpin, The Decline of the Union: British Government in Ireland 1892-1920 (Dublin, 1987), p. 188.

[3] For more details, see W. J. Lowe, ‘The War against the R.I.C., 1919-21,’ in Éire-Ireland xxxvii (2002), pp. 79-117; David Leeson, ‘The “Scum of London’s Underworld”? British Recruits for the Royal Irish Constabulary, 1920-21,’ in Contemporary British History xvii (2003), pp. 1-38; W. J. Lowe, ‘Who were the Black-and-Tans?’ in History Ireland xii (2004), pp. 47-51; D. M. Leeson, The Black and Tans: British Police and Auxiliaries in the Irish War of Independence, 1920-1921 (Oxford, 2011); Anne T. Dolan, ‘The British Culture of Paramilitary Violence in the Irish War of Independence,’ in John Gerwarth and John Horne (eds.) War in Peace: Paramilitary Violence in Europe after the Great War (Oxford, 2012) pp. 200-15; Tom Toomey, ‘The Black and Tans—who were they?’ http://irishistory.blogspot.com/2013/06/the-black-and-tans-who-were-they-black.html; Séan William Gannon, ‘The Black and Tans and Auxiliaries—An Overview,’ in The Irish Story. https://www.theirishstory.com/2020/01/13/the-black-and-tans-and-auxiliaries-an-overview/

[4] Service numbers 70984 to 71351, R.I.C. general register, T.N.A., H.O. 184/36-7, https://search.findmypast.co.uk/search-world-records/ireland-royal-irish-constabulary-service-records-1816-1922 (accessed 12 April 2019.)

[5] Ibid.

[6] General Annual Report on the British Army for the year ending 30th September 1921, Cmd. 1941 (1923), p. 6.

[7] ‘Military effectiveness, or combat effectiveness, probably cannot be strictly defined. It revolves primarily around the willingness, and only secondarily around the ability, of a military unit, large or small, to impose its will on the enemy.’ Roger R. Reese, Why Stalin’s Soldiers Fought: The Red Army’s Military Effectiveness in World War II (Lawrence, Kansas, 2011), p. 4; on the declining strength, efficiency, and effectiveness of the Royal Irish Constabulary, see Leeson, The Black and Tans, 16-24.

[8] Service numbers 71770 to 72190, R.I.C. general register, T.N.A. H.O. 184/37, https://search.findmypast.co.uk/search-world-records/ireland-royal-irish-constabulary-service-records-1816-1922 (accessed 12 April 2019). By October 1920, the proportion of British recruits with no recorded service experience had risen to 10 per cent: but still, 80 per cent of the Black and Tans who joined the force that month were ex-soldiers, while 8 per cent were ex-sailors, and 2 per cent were ex-marines: Leeson, The Black and Tans, pp. 70-1.

[9] Leeson, The Black and Tans, pp. 24-5.

[10] Richard Bennett, The Black and Tans (Reprint ed., New York, 1995), p. 38; D. G. Boyce, Englishmen and Irish Troubles: British Public Opinion and the Making of Irish Policy 1918-22 (London, 1972), 50; Townshend, British Campaign in Ireland, p. 94.

[11] Leeson, The Black and Tans, pp. 77-80.

[12] House of Commons Hansard, Commons Chamber, Oral Answers to Questions, Ireland, 25 Oct. 1920: http://bit.ly/2KyKFH8.

[13] ‘Black and Tans was the nickname given to a special auxiliary force of the Royal Irish Constabulary used by the British 1920-21 to fight the Sinn Feiners in Ireland; they wore uniforms of khaki with black hats and belts.’ ‘Berek,’ ‘Black and Tans,’ in Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Black_and_Tans&oldid=240758 (2 Jan. 2002).

[14] Leeson, ‘Black and Tans and Auxiliaries.’ For more details, see A. D. Harvey, ‘Who Were the Auxiliaries?’ in Historical Journal xxxv (1992), pp. 665-9; Lowe, ‘The War against the R.I.C.’; Leeson, The Black and Tans, esp. pp. 96-129; Dolan, ‘British Culture of Paramilitary Violence’; Ernest McCall, The Auxiliaries: Tudor’s Toughs (Newtowonards, n.d.); Paul O’Brien, Havoc: The Auxiliaries in Ireland’s War of Independence (Dublin, 2017); Gannon, ‘The Black and Tans and Auxiliaries.’. For many more details, see David Grant, The Auxiliary Division of the Royal Irish Constabulary. https://www.theauxiliaries.com/

[15] John Brewer, The Royal Irish Constabulary: An Oral History (Belfast, 1990), p. 103.

[16] To be fair, the cover of my own book The Black and Tans features a staged propaganda photograph of Auxiliaries pretending to search a captured Volunteer after an ambush. In my own defence, I would point out that my book is about the Auxiliaries as well as the Black and Tans—but in retrospect, I should have titled it The Black and Tans and Auxiliaries. On my choice of that picture for the cover, see D. M. Leeson, ‘The Black and Tans in black and white,’ in OUPblog. https://blog.oup.com/2011/09/black-and-tans/.

[17] 34. “The Black and Tans , [sic] or more properly known as the Royal Irish Constabulary Reserve Force, was [sic] one of the paramilitary forces employed by the Royal Irish Constabulary from 1920 to 1921, to deal with supporters of Sinn Féin and its military wing the IRA.” 68.42.11.91, ‘Black and Tans,’ in Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Black_and_Tans&oldid=4670803 (13:07, 16 July 2004)

[18] Elizabeth Malcolm, The Irish Policeman: A Life (Dublin, 2006), p. 48.

[19] Brewer, Royal Irish Constabulary, p. 83.

[20] County of Reserve, R.I.C. nominal returns by county, 1921, T.N.A., H.O. 184/62, ff. 10-16.

[21] ‘The Black and Tans was [sic] one of two newly recruited bodies, largely comprised of World War I veterans, employed by the Royal Irish Constabulary between 1920 and 1921 to suppress revolution in Ireland.’ ‘RashersTierney,’ ‘Black and Tans’ in Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Black_and_Tans&oldid=323931784 (18:29, 4 Nov. 2009).

[22] ‘The Black and Tans (Irish: Dúchrónaigh) was one of two newly recruited bodies, composed largely of British World War I veterans, employed by the Royal Irish Constabulary as Temporary Constables from 1920 to 1921 to suppress revolution in Ireland.’ ‘O Fenian,’ ‘Black and Tans,’ in Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Black_and_Tans&oldid=393027049 (17:08, 26 Oct. 2010).

[23] Toomey, ‘The Black and Tans’; Royal Irish Constabulary: general history of the force; ‘blue notes’ for 1922-1923, T.N.A. H.O. 45/14513. Toomey counts the temporary constables as ‘Black and Tans,’ but in my opinion, this is not correct.

[24] Pat Mahon to J. R. W. Goulden, 13 Feb. 1960, Trinity College Archives, Goulden Papers 7382a/153.

[25] Leeson, The Black and Tans, 108-10; Toomey, ‘The Black and Tans.’ My own research on the R.I.C.’s temporary constables has been poor. Unlike Toomey and Herlihy, who have gone through the whole general register, I relied on a cluster sample consisting of every recruit who joined the force in October 1920. As a result, it is unclear from my book just how many temporary constables joined the force, or even that some of them were attached to the regular R.I.C., while others joined the Veterans Division. At the time of writing, David Grant is researching these temporary constables for his website.

[26] Statement of Witness No. 29, D.I.2 and Adjutant Thomas Sparrow, ‘K’ Company Auxiliary Division R.I.C., in proceedings of a court of inquiry assembled at Victoria Barracks, Cork on the 16th December 1920 and five subsequent days, T.N.A. W.O. 35/88A, f. 87.

[27] An R.I.C. Christmas card from this period shows an Irish constable, a Black and Tan, an Auxiliary, and a temporary constable marching arm in arm: the clean-shaven Black and Tan, second from the left, wears a green policeman’s cap and a khaki soldier’s uniform; the temporary constable, on the right, wears a green cap as well, but with a blue uniform and a large white moustache: http://policehistoryni.com/new-R.I.C.-christmas-card.html.

[28] 45. ‘The Black and Tans (Irish: Dúchrónaigh) was one of two ad hoc paramilitary units, composed largely of British World War I veterans, employed by the Royal Irish Constabulary (R.I.C.) as Temporary Constables from 1920 to 1921 to suppress revolution in Ireland.’ ‘‘Kwekubo,’ ‘Black and Tans,’ in Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Black_and_Tans&oldid=481218592 (21:32, 10 Mar. 2012).

[29] H. H. Tudor to Under Secretary, 6 July 1920, T.N.A. H.O. 351/63.

[30] Leeson, The Black and Tans, p. 26; Toomey, ‘The Black and Tans.’

[31] ‘The Black and Tans (Irish: Dúchrónaigh) were men from Great Britain who joined the Royal Irish Constabulary (R.I.C.) as Temporary Constables during the Irish War of Independence.’ ‘Asarlaí,’ ‘Black and Tans,’ in Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Black_and_Tans&oldid=527467971 (3:39, 11 Dec. 2012).

[32] At the time of writing, the article’s links to the National Defense Intelligence College and its Press were dead, but it provided another link to a page that was archived at the Wayback Machine in 2009: https://web.archive.org/web/20090327013025/http://www.ndic.edu/press/pdf/5463.pdf. A web search will reveal, however, that the National Defense Intelligence College became the National Intelligence University in 2011, at which point (presumably) the National Defence Intelligence College Press became the National Intelligence (NI) Press. The current link to this publication (accessed 12 Apr. 2019) is http://ni-u.edu/ni_press/pdf/Improving_the_Law_Enforcement_Intelligence_Community.pdf

[33] Kostal, p. 119. To be fair to Kostal, a number of publications mention Mar. 1920, and even 25 Mar. 1920: see, for example, Bennett, The Black and Tans, p. 36. But, as the R.I.C. general register makes clear, the first British recruits had joined the force in Jan. 1920, and had been assigned to their stations in Feb. An article in the Connacht Tribune, for example, mentions the first sighting of ‘English ex-soldier R.I.C. recruits’ in Galway on 24 Feb. (‘Khaki Policemen: English Recruits in Galway,’ Connacht Tribune, 28 Feb. 1920, p. 5).

[34] See Kostal, pp. 118, 121, and 122, for images taken from Wikipedia.

[35] ‘The Black and Tans (Irish: Dúchrónaigh), officially the Royal Irish Constabulary Reserve Force, were a force of Temporary Constables recruited to assist the Royal Irish Constabulary (R.I.C.) during the Irish War of Independence.’ ‘Degen Earthfast,’ ‘Black and Tans,’ in Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Black_and_Tans&oldid=644267590 (16:12, 26 Jan. 2015).

[36] ‘Don’t be too tragic about Ireland,’ The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/news/1921/oct/12/mainsection.fromthearchive. It is not clear when this leader was published online.

[37] ‘The Black and Tans (Irish: Dúchrónaigh), officially the Royal Irish Constabulary Special Reserve, was a force of Temporary Constables recruited to assist the Royal Irish Constabulary during the Irish War of Independence.’ ‘Asarlaí,’ ‘Black and Tans,’ in Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Black_and_Tans&oldid=694799582 (17:07, 11 Dec. 2015).

[38] Pat Poland, ‘The burning of Cork, December 1920: the fire service response,’ in History Ireland xxiii (2015): http://www.historyireland.com/volume-23/the-burning-of-cork-december-1920-the-fire-service-response/; John Reynolds, ‘Divided loyalties: The Royal Irish Constabulary in county Tipperary, 1919-1922’ (Ph.D. dissertation, University of Limerick, 2013): https://ulir.ul.ie/handle/10344/3618.

[39] D. M. Leeson, ‘Phantom Force: The “Royal Irish Constabulary Special Reserve,”’ History Ireland xxx (Sep./Oct. 2022): 14-15.

[40] Leeson, The Black and Tans, 200-2.

[41] Constable 74281, R.I.C. general register, TNA HO 184/38, https://search.findmypast.co.uk/search-world-records/ireland-royal-irish-constabulary-service-records-1816-1922 (accessed 13 Apr. 2019). I then went on to repeat this error in D. M. Leeson, ‘The Murder of Patrick Howard: A Case Study of Police Crime in the War of Independence,’ in Éire-Ireland xlvii (2012), p. 128.

[42] Reynolds, ‘Divided loyalties,’ p. 83: idem, 46 Men Dead: The Royal Irish Constabulary in County Tipperary, 1919-22 (Kindle ed., Dublin, 2016), l. 1047.

[43] John Reynolds to author (email message), 30 Nov. 2018.

[44] John Reynolds to author (email message), 5 Dec. 2018.

[45] Royal Irish Constabulary: general history of the force; ‘blue notes’ for 1922-1923, T.N.A., H.O. 45/14513.

[46] Research into the history of the U.S.C. has lagged behind that of other police forces in revolutionary Ireland, but for more details (and contrasting perspectives), see Arthur Hezlet, The ‘B’ Specials: A History of the Ulster Special Constabulary (London, 1972); Michael Farrell, Arming the Protestants: The Formation of the Ulster Special Constabulary and the Royal Irish Constabulary, 1920-7 (London, 1983); John Ó Néill, ‘Taking Matters into their own hands: The Ulster Special Constabulary,’ in The Irish Story. https://www.theirishstory.com/2020/01/22/taking-matters-into-their-own-hands-the-ulster-special-constabulary/

[47] Ó Néill, ‘Taking Matters into their own hands’

[48] Hezlet, The ‘B’ Specials, p. 20.

[49] Royal Irish Constabulary: general history of the force; ‘blue notes’ for 1922-1923, T.N.A., H.O. 45/14513.

[50] Hezlet, The ‘B’ Specials, p. 20.

[51] The legislation in question is 2 & 3 Vic., c.75: Malcolm, The Irish Policeman, p. 48.

[52] McCall, Tudor’s Toughs, p. 26.

[53] ‘One of the problems with the Auxiliaries and the Black and Tans is that they are always mistaken by people who are writing about them.’ McCall, Tudor’s Toughs, p. 39.

[54] At the beginning of 2020, as part of its Decade of Centenaries program, the Government of Ireland announced that it would hold a service at Dublin Castle in memory of those who lost their lives while serving in the Royal Irish Constabulary and the Dublin Metropolitan Police during the struggle for Irish independence. This announcement caused a great public controversy: the Black and Tans had been members of the Royal Irish Constabulary—was the Government of Ireland seriously proposing to commemorate the Black and Tans? In response to this outcry, the government cancelled the planned memorial. In the middle of this affair, on 8 January 2020, an Irish Wikipedian called Jdorney began a series of edits to Wikipedia’s article on the Black and Tans by deleting any reference to the ‘R.I.C. Special Reserve.’ Five days later, on 13 January, The Irish Story published an excellent short article on ‘the Black and Tans and Auxiliaries’ by Séan William Gannon, an emerging expert on the British police forces in revolutionary Ireland: ‘They were not ‘temporary constables’ or a ‘special reserve,’” says Gannon. I have recently confirmed that Jdorney is John Dorney, author of two books on the Irish revolutionary period, and editor and administrator of The Irish Story.