‘Riot of Plunder’: Rural revolt in May 1922

By Terry Dunne

In his 1923 memoir Lord Castletown gave us a standard conservative account of the spring of 1922 – “a very unsettled one in weather and life conditions”.[1] Castletown, the heir of the old Gaelic dynasty the Mac Giolla Phádraigs, complained of “chaos and disorders” which “broke out everywhere”. He continued: “we had attempts at cattle driving, non-payments of rents, etc.., and many farmers, Protestant and Catholic, suffered.”

Castletown ascribed the source of these problems to the fact that “De Valera and his associates were bent on making this poor country impossible to live in.” On the contrary, at least at leadership level, both the forces of the new Irish Free State, and the anti-Treatyites, or “De Valera and his associates”, were trying to prevent cattle driving.

A joint pro and anti-Treaty IRA proclamation in County Kilkenny in May 1922 declared that “cattle driving and all such operations arising from agrarian trouble shall immediately cease.”

For instance, on the 8th of May 1922 a proclamation was issued in County Kilkenny in the name of both wings of the Irish Republican Army, signed by, amongst others, Ned Aylward, on behalf of the New Executive (anti-Treatyites), and John T. Prout, on behalf of the G.H.Q. (pro-Treatyites).[2]

The first point in the Kilkenny proclamation read: “throughout the County and in the adjoining areas cattle driving and all such operations arising from agrarian trouble shall immediately cease.”

The background for this statement was a new agrarian movement reprising the movement of 1920 that had attempted to drive ‘ranchers’ cattle off farmland and reclaim it for small farmers. That was not the whole of the context however – the rival pro and anti-Treaty IRA factions had only recently shot up Kilkenny city in a series of fortunately fatality-free firefights and were now trying to avoid future clashes.

Their local compact was only one part of a wider national peace process seeking to prevent such parochial excitements pitching into full-scale Civil War over the Treaty.

Common agendas?

Contrary to the sometime framing of the subsequent Civil War in left/right terms, in this statement we see both sides of the imminent conflict acting to suppress agrarian protest.

Though one might argue in this instance part of the reason for that attempted suppression was indeed the possibility that elements of the rival separatist factions would take part in agrarian protest. That certainly seems to be the framing of this proclamation.

We have to be conscious of the possibility of the rank and file or local leaders of a citizen-soldiery paying little attention to the stated policies of headquarters. In any case, the Kilkenny instance is not at all the only one where pro and anti-Treatyites mobilised against agrarian insurgency in this period. In west Mayo for instance James Chambers, O.C. of the local anti-Treatyites, threatened “action of drastic nature”;[3] while in north Clare cattle drivers conducted their own miniature guerrilla war against both sides.[4]

The 1922 Movement

The 1922 agrarian movement does not seem to have had quite the sudden tempo of its 1920 predecessor. But the movement in 1922 seems to have encompassed a broader spread of the country. While the hotspot in 1920 was the east Connacht plain, in 1922 little fires were alighting almost country-wide.

The Irish Independent of the 11th of May 1922 claimed “agrarian trouble has spread through three provinces, while cattle driving has become more prevalent”.[5] The May 8th proclamation’s Kilkenny provenance was not an accident, there were many occasions of militant agrarian mobilisation in the broad region around Kilkenny.

On the 6th of May the Irish Independent reported of Tipperary, to the immediate west of Kilkenny, that: “Longford Manor, Cashel, occupied by Mr. Vere R. Hunt was attacked by armed men, and the firing, which lasted two hours, was replied to. The same night 200 cattle were driven off the lands.

Having driven off the cattle, men took possession of the lands of Castleotway, Templederry, Nenagh ; and 26 cattle were driven from the lands of Mr. R. E. Bayly, Debsborough, Nenagh.”[6]

Early 1922 saw very widespread land occupations by poor farmers on landed demesnes and big ‘ranches’, described by the Freeman’s Journal as ‘a riot of plunder’.

The same issue of the same newspaper reported a novel adaptation of the repertoire in Waterford, to the south of Kilkenny. Here cattle were not driven off land, but driven on to it. The paper reported:

“About 100 cattle were driven on to the lands of Major H. J. Chearley, Salterbridge, Cappoquin, and a letter sent to the steward warning him not to interfere with them.”

On the 3rd of August 1922 the mansion at the aforementioned Castleotway would be burned to the ground.[7]

Four days before the joint proclamation against cattle driving, drives took place on three properties near Galmoy, in north-west Kilkenny.[8] In two of the instances these took the classic form of the removal of cattle and sheep from an outlying farm and their delivery to their owners’ home premises. In this case to brothers Richard Ringwood, of Eirke (sometimes Erke) House, and A. G. Ringwood, of Tullyvolty House. The drivers had the effrontery to demand payment for moving the animals. Daniel Hickey of nearby Rathpatrick House was also targeted.

Tragically illness had gripped the household of Richard Ringwood, much of which was bedridden, and his son died the very night of the drive. Richard Ringwood was a noted activist within the Kilkenny Farmers’ Union.[9] In the following year, 1923, the Ringwoods were again targeted, this time with sabotage.[10]

Later in the month of May 1922, near Roscrea, along the Tipperary/Offaly border, the mansion at Golden Grove was subjected to attack and attempted arson.[11] This was followed by an assembly of persons from Roscrea who descended on the property with donkeys and carts and proceeded to “remove all the portable articles around the house” including plants from Golden Grove’s famed conservatory.

Contrary to the stereotype of anti-Treatyites as radical wild men, troops from Roscrea’s anti-Treaty IRA detachment arrived to put an end to proceedings and put a guard on the premises. A ‘Riot of Plunder’ is what the Freeman’s Journal called this event.

There is also from north Tipperary the report of the kidnapping of Ludlow M. Jones of Knocknacree House, near Cloughjordan.[12] Jones, a prominent land agent, was kidnapped from his office in Nenagh and the estate papers he held in the office were taken with him. The following year his mansion house was left a smouldering ruin.[13]

These are just a sample of reported events. Of course sometimes it is hard to know exactly what was going on without a more in-depth inquiry into an individual occurrence.

It is worth nothing that while we can identify these particular highpoints, in 1920 and again in 1922, in some instances there was likely to have been continual contention on a lower-level. According to the account given to the Irish Grants Committee of the Gore properties in east Clare there was “continuous persecution, intimidation, and boycotting” from 1920 onwards.[14] The 1918 cattle drives that took place there, and are reported in the newspapers, are not even mentioned in the statement.[15]

It is also worth noting that the renewed agrarian mobilisation of this 1922 period was simultaneous with the radical zenith of the workers’ movement in the form of the Munster creamery soviets.

The Wider Mentality

Certain forms of possession and/or use of land were widely delegitimised. A good example of this is the maudlin editorialising on the situation in Luggacurren, in south Laois, contained in the Nationalist and Leinster Times (the local newspaper for Laois, Carlow, and south Kildare). The commentary referred to holdings from which tenants had been evicted during a rent strike in the movement of many decades previous known as the Plan of Campaign. The paper claimed:

“A strong movement is on foot to regain possession of some of the Lansdowne property in Luggacurren, and it is expected that the work will result in once again having the people who were owners, or their descendants, planted on the soil where in the ‘Eighties they were ruthlessly thrown out on the roadside and a band of black Cromwellian planters installed in all the panoply of war into the once happy, smiling little homesteads of the people, who, in most cases, were forced to seek the shelter of the poorhouses or the emigrant ship to be swallowed up in the flotsam and jetsam of New York, or some American city to act as hewers of wood or drawers of water with broken hearts, whilst a foul brood of foreign vultures, fattened on the fruit of the people’s toil in the once happy vale of Luggacurren.”[16]

As it happened, the evicted tenants had already been re-instated on the estate, and, at least according to some reports the people organising the expulsion of the so-called “planters” were not at all the hitherto dispossessed tenants.[17]

Of course if everyone would reclaim land from which their forbearers had been evicted then the result would be as it was near Gorey, Wexford, also in early May 1922. There, in a place called Mount Howard, there was a shoot-out between, on the one hand, a family named Murphy, backed up by supporters, and on the other hand a family named Tomkins. Seemingly James Murphy claimed the land on the basis his grandfather had been evicted from it 35 years before.[18]

‘Ranching’ and its detractors

The ‘rancher’ was the ever-present target of agrarian agitators in this period. An example of the extensive denunciation of this particular pattern of land possession and use, as being anti-social and illegitimate, is given by the fact that even the Kilkenny Farmers’ Union debated the question “what ranching really is”.

The aforementioned Richard Ringwood was involved in this group, which was generally seen as a conservative force representing the interests of larger farmers. They debated the issue in response to a questionnaire from the national structures of the Irish Farmers’ Union. The conclusion reached was the minimum definition — “ranching was confined to big demesnes where labour was not employed”.[19]

Ranching, within the worldview of at least some Irish nationalists, represented de-population and de-industrialisation and dependency. This was because it was a low-input form of farming, with little scope for employment or fixed capital investment, and amounted to simply the export of an unprocessed raw material. In this respect, it very much fitted into a colonial or neo-colonial pattern of development —wherein a periphery is confined to exporting cheapened labour, raw materials and food, to an industrialised core.

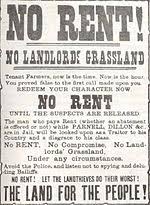

‘The Land for the People’ slogan was part of a wider nationalist idea that Ireland could be rescued from the patterns of economic development that had led to poverty and emigration.

Memory’s rhetoric has it that ‘the Land’ was returned to ‘the People’ in the Land Acts from the 1880s onwards in which tenants were subsidised to buy their holdings from the old landlord class.

However, despite this common and charmingly uncomplicated formulation, the idea that ‘the Land’ had to be returned to ‘the People’, opened up a whole wormery of potential new issues. Leaving aside the matter that landlords were also, in fact, people, all Irish people were not landholders, nor was there an equity in the distribution of land among the segment of the population who became landowners in the wake of the Land Acts.

Even more perversely, one might argue that if you were a landholder in the early-twentieth century it was by virtue of, at least partly, the relationship your kin had forged with landlords. Nonetheless Irish nationalism’s discursive formulations on agrarian matters had within them the potential for all kinds of claims and re-workings of what ‘The Land for The People’ would mean or could mean.

So, while participants in much of the militancy discussed here are at times dismissed as simple opportunistic rustics, they in fact operated according to ways of thinking widely accepted at the time.

Accepted, it might be added, however grudgingly, even by the most conservative strands within Irish nationalism. Kevin O’Higgins, for instance, who as the Free State’s Minister for Home Affairs oversaw an extensive crackdown on agrarianism in 1923, earlier showed himself at least somewhat sympathetic towards rallies for ‘The Land for The People’.[20] Irish nationalist movements had spent more than 40 years invading property rights, and that was something hard to claw back from.

The Little Social Revolution That Did

There is a literature that maintains there was no revolution in Ireland, which in sum amounts to a conflation of revolutionary situation, that is dual sovereignty and mass participation in related conflict, and revolutionary outcome, that is a linked period of dramatic social change.

To encompass some of the latter we surely need a chronologically broader focus, which indeed leaves a less neat periodization than a revolution which starts with the Home Rule crisis and ends with the Civil War.

But not that broader: in 1900 less than 15% of tenant occupiers had begun land purchase, and the local government reform which curtailed the local political power of the landlord class was a mere two years old.[21]

While we can read events in terms of a sweeping transition from the dominance of one nationalist party to another, on the ground a lot of what was happening after 1917 was an intensification and transformation of pre-existing forms of popular struggle.

Those processes were interlinked in complex ways with the broad campaign for independence. For instance, the massive growth in trade unionism contributed significantly to the independence drive, while, paradoxically, the separatist Dáil authorities’ clamp-down on small-farmer protest did likewise, in terms of contributing to the Republican counter-state.

The Irish Republican movement was nervous of land agitation but enabling land purchase by tenant farmers remained one of its core economic and social goals.

A total of 392,704 acres of so-called untenanted land was acquired by the Irish Free State for re-distribution between the Land Act of 1923 and the removal of Cumann na nGaedheal from government in 1932. In the first five years of the Irish Free State an average of 50,000 acres per year was re-distributed.

In all in the first almost two decades of the Irish state’s existence (1922 to 1940) an area equivalent to County Louth four times over was allotted to new recipients under the 1923 and 1932 Land Acts.[22]

Despite this extensive reform, for a long time an historiographical premise was that the land question had been settled prior to the revolution.[23]

The bulk of published research concerns military contests and high politics, precisely the topics least likely to give us evidence speaking to such questions as was there a social revolution, or just a political revolution, or was there a thwarted social revolution, or alternatively no revolution at all. To evaluate the social dimensions of the revolution necessitates a research agenda that goes beyond the whizz-bang of the Flying Columns and a top-down reading of the doings of politicians.

This is based on research for a new series of Terry’s podcast https://peelersandsheep.ie/ and you can read some of the outputs he made as Laois Historian-in-Residence here https://laoislocalstudies.ie/articles/

References

[1] Lord Castletown, Ego: Random Records of Sport, Service and Travel in Many Lands (London, John Murray, 1923), p. 233.

[2] Waterford News and Star, 12 May 1922. Aylward, then a T.D. (Member of Parliament), and previously a noted guerrilla leader, went on to emigrate to the United States, but came back to Ireland and worked as a meat plant manager. Prout, a U.S. military veteran, did not make a future for himself in the new Irish Free State, returned to the United States, and later played a minor role in Hollywood as an advisor on the James Cagney World War One movie ‘The Fighting 69th’.

[3] Evening Echo, 29 May 1922.

[4] Irish Independent, 27 May 1922; Irish Independent, 3 June 1922; Freeman’s Journal, 3 June 1922.

[5] Irish Independent, 11 May 1922.

[6] Irish Independent, 6 May 1922.

[7] Freeman’s Journal, 5 August 1922.

[8] The Moderator, 13 May 1922.

[9] The Moderator, 20 May 1922.

[10] The Moderator, 1 September 1923.

[11] Freeman’s Journal, 20 May 1922.

[12] Freeman’s Journal, 5 May 1922.

[13] Nenagh Guardian, 10 February 1923.

[14] CO 762 Irish Grants Committee, County Clare extracts, Page 1347, Comm. Reginald Gore (original in Kew, Clare extracts copy held in Clare Local Studies Library).

[15] Limerick Leader, 21 January 1918.

[16] Nationalist and Leinster Times, 18 March 1922.

[17] Leigh-Ann Coffey, The Planters of Luggacurran, County Laois: A Protestant community, 1879‒1927 (Dublin, Four Courts Press, 2006), pp.53‒58.

[18] Freeman’s Journal, 6 May 1922.

[19] The Moderator, 16 December 1922.

[20] Nationalist and Leinster Times, 24 April 1920; Nationalist and Leinster Times, 16 March 1918.

[21] Samuel Clark and James S. Donnelly Jr., ‘Introduction’ in Samuel Clark and James S. Donnelly Jr. (eds), Irish Peasants: Violence and Political Unrest 1780‒1914 (Dublin, Gill & Macmillan, 1983), p.272.

[22] Tony Varley, ‘The politics of ‘holding the balance’ Irish farmers’ parties and land redistribution in the twentieth century’ in Tony Varley and Fergus Campbell (eds), Land Questions in Modern Ireland (Manchester, Manchester University Press, 2013).

[23] Olivier Coquelin, ‘Class Struggle in the Irish Revolution: A Reappraisal’ in Études irlandaises

42-2, 2017.