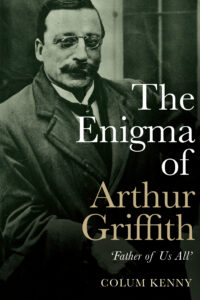

Book Review: The Enigma of Arthur Griffith: ‘Father of us all’

By Colum Kenny

By Colum Kenny

Published by Merrion Press (2020)

Reviewed: Eoin O’Driscoll

We are approaching the end of Ireland’s Decade of Centenaries (2012-2023). The programme has largely been a success. In the context of a growing international tide of xenophobic nationalism – an era sadly defined by Donald J Trump, Jair Bolsonaro and Viktor Orban – Ireland’s 2016 commemorations, marking the centenary of the Easter Rising demonstrated an all-too rare maturity of historical perspective.

However, as recognised by Minister Catherine Martin in her foreword to the 2021 Centenary Programme, we have entered the most challenging and sensitive period of commemoration. As the 2020 controversy over the planned Commemoration for the Dublin Metropolitan Police and Royal Irish Constabulary demonstrated, Ireland’s people can continue to be divided by its history.

Amidst broad public outcry and with the event’s eventual cancellation, then Minister for Justice Charlie Flanagan’s appeal that “the approach to the Decade of Centenaries has made clear that there is no hierarchy of Irishness and that our goal of reconciliation on the island of Ireland can only be achieved through mutual understanding and mutual respect of the different traditions on the island” rang hollow.

Fault lines based on how we understand and how we define “Irishness” retains the power to divide. And respect between opposing camps appears at a premium. In this context, Colum Kenny’s “The Enigma of Arthur Griffith: Father of us all” is a timely publication.

Though Griffith is recognised as one of the State’s founding fathers, his contribution to the historic movements from which the State emerged are often overlooked.

Though Griffith is recognised as one of the State’s founding fathers, his contribution to the historic movements from which the State emerged are often overlooked. Historical attention has focused on the more glamorous figures of Michael Collins, Éamon de Valera and Padraig Pearse. Despite his central role in the development of the Irish nationalism from which the Irish State would emerge, Griffith has had to settle for a side line role in the national historical memory.

Repeated charges of an “un-Irish” character that dogged Griffith throughout his career in public life continue to shape how he is remembered. Kenny’s biography runs counter to this dominant narrative. He draws attention to Griffith’s pivotal role as a key figure in the development of Irish nationalism and his enduring legacy, far beyond solely his role in the negotiation of the Anglo Irish Treaty.

Kenny’s account of the active erasure of Griffith from Ireland’s national pantheon by his friends turned rivals (notably WB Yeats and Éamon de Valera) grants a compelling insight into how a national memory was forged in the year’s following Griffith’s death. In Kenny’s words, “unlike Griffith himself, contemporaries who survived to old age were free to shape his reputation”.

They did not seek to elevate him. Rather, Griffith’s reputation and impact was undermined in the Irish national memory. It is particularly poignant that the beginnings of this process were already all too evident as Griffith’s health was in evident decline towards the end of his life, worn haggard by the pressures of the Treaty negotiations and the ensuing Civil War.

Less than a year after his death, when the Government’s Griffith Settlement Bill, seeking to make provision for the Griffith family, passed through the Oireachtas, precious few TDs or Senators took the opportunity to pay him tribute.

While Kenny emphasises Griffith’s significance in Irish history, those seeking a hagiography of the man who founded Sinn Féin should look elsewhere. Kenny’s Griffith is complex. He was a man far from immune to the prejudices of his time as seen in his publication of a number of anti-Semitic articles. Kenny is quite critical of Griffith’s judgement during arguably the key moment of his career, his agreeing to the Border Commission as part of the Anglo Irish Treaty.

Nonetheless, as is evident from Kenny’s work, Griffith is a historical figure deserving of a reappraisal. His contribution to the development of the Irish national movement was unparalleled. In certain regards, he was a man of great vision with a view of Irish nationalism far more pluralistic that those of many of his contemporaries and indeed than many of his successors in leading the nascent Irish state.

It is this aspect of his political thought, so central in shaping the Irish nation that emerged, that bears relevance to contemporary debates around Irish identity.

For Kenny’s Griffith, Irish independence was a practical project. Griffith’s home was Dublin’s slums, one of the most egregious examples of urban poverty in late 19th and early 20th Century Europe.

Born but a generation after the Great Famine, Griffith believed that it was only through self-rule could Ireland hope to avoid the calamities of the past and alleviate the suffering and privations of its people.

In Kenny’s view (re-appropriating Griffith’s assessment of John Mitchel) Griffith “cared not tuppence for republicanism in the abstract”. In this regard, Griffith stands in stark contrast to the more romantic notions of nationalism, best exemplified by Padraig Pearse, that would come to the fore in 1916.

Griffith’s compromises or ‘doggged pursuit of the tangible’ included his dual-monarchy proposal, and willingness to make the compromises that would underpin the Anglo Irish Treaty.

It was, however, within this dogged pursuit of the tangible – the realisation of nationhood as a reality – that Griffith opened himself up to the criticism that has most strongly tainted his legacy. Griffith’s dual-monarchy proposal, which he viewed as an acceptable compromise to co-opt the large Unionist minority into a new Irish State and his willingness to make the compromises that would underpin the Anglo Irish Treaty were critiqued for their departure from the ideals of Irish Republicanism.

So too have his pro-enterprise ideals served as the anathema to left-wing critics enamoured with the possibility of the emergence of a socialist Irish state, shorn of the industrialist and the landlord. And yet, it was these compromises that allowed the ideal of an Irish State to become a reality. Politics is the art of the possible. Compromise is at the core of its practice, as distasteful as that is to some. Imperfect though the reality of independence may have been, few could seriously contend that the culmination of Griffith’s compromises, in today’s Irish Republic, has not been a notable success.

It is in his dogged pursuit of the tangible that Griffith, as portrayed by Kenny, appears most impressive and most unusual amongst his peers. It is easy to hurl from the ditch, as Griffith’s contemporary critics were all too quick to do. Griffith’s contemporary, US President Teddy Roosevelt said “it is not the critic who counts; not the man who points out how the strong man stumbles, or where the doer of deeds could have done them better. The credit belongs to the man who is actually in the arena”.

While De Valera avoided communiques from the negotiators in London, it was Griffith who stood up to the mark and made the compromises that would define the emergent Irish Free State. He would pay dearly for doing so but as the relevance of the Irish Civil War dwindles, surely the historical record lands firmly in his favour?

Overall, Kenny’s biography is compelling and insightful read for anyone seeking to better understand one of Irish history’s more enigmatic characters.

Kenny’s The Enigma of Arthur Griffith is at its strongest in utilising other figures in the period to show not only lesser known influences of Griffith but also to effectively contextualise the Irish leader within his time. Kenny gives unusual insight into how Irish nationalism in the early 20th Century was a product not only its time but also the heavy hand of Irish history, notably the Great Famine and the legacy of the failed Young Ireland uprising. Of particular interest in understanding Griffith’s character as Kenny’s recounting of Griffiths’ position within Ireland’s cultural milieu and the intertwining of political nationalism so closely with the nation’s literary revival.

Less compelling are Kenny’s occasional truncated invocations of psychological analysis including allusions to Jungian archetype. If such analysis serves to provide insight into Griffith’s assessment as a historical figure, further elucidation than provided is required.

Overall, Kenny’s biography is compelling and insightful read for anyone seeking to better understand one of Irish history’s more enigmatic characters. Hopefully, Kenny’s represents the start of increased interest in his subject.