The assassination of Walter Edward Guinness -Lord Moyne – 1944

By Ray Esten

The foundation stone of a building at Trinity College Dublin was laid by the Hon. Grania Guinness of the philanthropic brewing family in February of 1950. Grania named the Institute of Preventative Medicine ‘Moyne’ in memorial to her late father Baron Moyne.

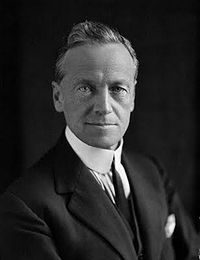

Dublin-born Walter Edward Guinness, late known as Lord Moyne, served as British Secretary for State for the Colonies and Minister Resident in the Middle East, until he was assassinated by the militant Zionist group, Lehi in Jerusalem on November 6, 1944. His death was one of the steps on the road to the British withdrawal from their Mandate in Palestine in 1948 and the creation of the state of Israel.

He was an advocate of compromise between Arabs and Jews in Palestine and his death hastened the onset of a conflict in Israel-Palestine that continues to this day.

Early life

Walter Edward Guinness as he had been formerly known was born in Dublin in 1880 and educated at Eton in England, the third son of the benevolent Lord Iveagh[1] who had also been a benefactor to Trinity College.

Described as charming, discerning, and astute, Walter Edward Guinness would carve out a hugely successful career for himself in politics. His true passion, however, revolved around the pursuit of biology including zoology, and anthropology for which he collected a wide variety of ethnographic objects.

However, his plans to undertake biological pursuits were thwarted by the South African War 1899-1902, for which he volunteered as a captain in the Suffolk Hussars, with whom he served with distinction until the war’s end in 1902.[2] His life nearly cut short when a bullet entered his head near the cheek, narrowly missing the brain.

Walter Edward Guinness would carve out a hugely successful career for himself in politics but his true passion was biology and anthroplogy.

It is uncertain why he gravitated towards politics, but he served the London City Council, prior to being elected Conservative Member of Parliament for Bury St Edmonds from 1907. He returned to military service during the First War 1914-1918 (in France and Gallipoli) and his outstanding service as a staff officer earned him the unusual double honour of a Distinguished Service Order and a bar.

Other political posts included Under Secretary of State of War, Financial Secretary to the Treasury, and from 1924 to 1925, Minister for Agriculture and Fisheries.[3]

Irish Affairs

Lord Moyne (as he shall be referred to from this point) kept a residence at the stunning Knockmaroon Estate in Castleknock Dublin and he remained keenly interested in the affairs of his home country.

After the 1916 Rising he quoted a statement by Home Rule MP Joseph Devlin that any settlement of the Irish question must involve amnesty to the Irish rebels recently condemned to imprisonment and penal servitude.[4]

However, he was of the view that granting Home Rule in the wake of the Rising would be ‘surrender to Sinn Fein’ and helped form the ‘Imperial Unionist Association’ with fellow peers, Lords Middleton and Salisbury.[5] He was also perplexed and queried the Prime Minister about that clerks in government employment, for instance, Patrick Kelly who had fought in the Rising (in the garrison at Jacobs Biscuit Factory) having returned to government employment.[6]

Lord Moyne was a unionist but preferred all-Ireland Home Rule to partition.

If he was against Home Rule, however, he was even more against Home Rule with partition, as introduced by the Government of Ireland Act in 1920. By 1920 he had distinguished himself as the leader of the band of young Unionists who tried to remove partition from the Home Rule Act –the Unionist anti-Partition League. He was against Dominion Home Rule; but felt that the time had come when southern unionists must be prepared to sacrifice their ideal settlement rather than allow the country to ‘drift further along the road to disaster’.

He had obvious fears about the future and called for a ‘commonwealth’ which could not be ‘twisted into a term of race inferiority’.[7] Notably he feared that the strength of southern unionists would be diminished and considered proportional representation as a valuable safeguard, though he worried that the mathematical system would leave unionists with few seats.[8]

It would seem that he had been in communication with Dail Eireann during the week ending April 16, 1921, for Lieutenant Commander Kenworthy asked the Prime Minister if he was aware of such communications between the Hon. Member (Moyne) and those sought for arrest by the government.[9] There had been secret negotiations and news broke that July of a truce which had been arranged between the Crown forces and the Volunteers to enable negotiations to take place between the British government and representatives of the Irish government established by the Dail.

The Anglo-Irish treaty was signed on 6 December 1921. It proposed to establish the Irish Free State as a fully self-governing Dominion of the British Empire but effectively excluded the six counties of Northern Ireland.[10] In view of the altered situation and the resolution of parliament, Lord Moyne and the Unionist Anti-Partition League felt that its best efforts must be to secure the co-operation of all in establishing a stable government in the south of Ireland. [11]

He remained apprehensive about a lasting resolution to the Irish question and felt that the withdrawal of troops from the country would result in ‘tribal warfare’.[12] His concerns were proved not to be far wrong as civil war broke out in June of 1922.

The Treaty of Versailles and international outlook

World War I ended in 1918 as Germany signed an armistice ending hostilities. In February of 1919 Lord Moyne (who had returned from the war and wrote a harrowing account of his experiences fighting the Germans)[13] asked Lloyd George ‘if the right Hon Gentleman was going to press to the utmost extent of his power that Germany should pay to the fullest extent of her financial resources’.[14] In other words, Moyne was for a punitive peace with Germany.

Moyne wanted Germany to ‘pay to the fullest extent of her financial resources’ in reparations for the Great War.

The Treaty of Versailles was signed that June and a controversial War Guilt clause was inserted by the hawks like Lord Moyne, whose view of the war saw Germany as the sole cause of the conflict and demanded heavy war reparations as a consequence.

In broader terms, he articulated his concern about the Bolshevik revolution in Russia and expressed concerns at the policy of Mr. Lloyd George in Greece who had promised territorial gains to the Greeks at the expense of the Ottoman Empire who had suffered defeat in World War I. However, instead of victory the Greeks had been wholly defeated by a Turkish counterattack led by Kemal Ataturk.[15]

Philanthropy

Lord Moyne had worked in the family brewing business, at the famous Guinness plant in Dublin, momentarily and continued the family’s philanthropic legacy, by bestowing exotic animals on London Zoo. The Moyne collection in the British Museum lists 426 items.[16]

He also entrusted rare works to the Royal Irish Academy[17] and other items like ‘ ‘The true Account of the Siege of Londonderry, ‘’by Geo. Walker to Queen’s University Belfast, the Linen Hall Library, libraries in Armagh and the National Library of Scotland and the Natural Central Library.[18]

By 1932 he received a peerage and this is when he chose the title Moyne. It had a family connection and was taken from a map of Loch Corrib, County Galway, and Mayo. It was after this that he became the leader of the House of Lords, Secretary of State for the Colonies, Resident Minister in Cairo and finally Colonial Secretary. [19]

Lord Moyne and Palestine

British forces had conquered much of the middle east, taking it from the Ottoman Empire during the First World War, including the new states of Iraq, Jordan and Palestine.

The mandate issued by the League of Nations after the First World War gave Britain full administrative control over the region[20] and included provisions for establishing a homeland for the Jews in Palestine (in accordance with the Balfour declaration of 1917) which went into effect in 1923.

However, there was, as yet no rush of eager Jewish volunteers to build up the ‘’national homeland’’; on the contrary, an average of only eight or nine thousand Jewish immigrants a year came to Palestine between 1920 and 1932. Yet from 1933 onwards, however, this changed dramatically, with the Nazis in control in Berlin.[21]

The British mandate of Palestine protected Jewish immigration to Palestine at first, but with mounting Arab resistance by the 1930s, took the decision to limit Jewish settlement thereafter.

The Arab population of Palestine, alarmed at the influx of Jewish immigrants, revolted en masse, in 1936 and this ushered in three years of strife as they tried to end British rule[22] while endeavouring to establish Arab independence and an end to Jewish immigration. The British put the revolt down harshly, but also decided thereafter to limit Jewish immigration in order to try to prevent further conflict.

Nevertheless, the Second World War found the three protagonists, the British, the Arabs, and the Zionists unreconciled. Furthermore, the most militant Zionist organisations now began a campaign of political violence against the British authorities, who, though they had overseen the establishment of Jewish settlement in Palestine, they now viewed as blocking their dream for a Jewish state there.

Yitzhak Shamir, a leading member of Stern gang and later Prime Minister of Israel (and according to Dr. Shavit, the chief planner of the murder of Lord Moyne[23]) noted that the relations between their mandatory authorities and our ‘state within a state’, ‘tended to be schizophrenic at best’. [24]

Meanwhile, the Arabs viewed the Jewish influx as part of a European colonial movement, and the period was marred by violence on all sides. The Irish Examiner, for instance, reported an incident in June of 1939 in which Jews raced through the streets in fast cars like American screen gangsters pouring out a stream of led that killed twelve Arabs, wounded four others and one Jew.[25]

It was this complex, three-sided conflict that Lord Moyne came to preside over in Palestine as resident minister of state in 1942 and British ‘Minister-Resident’ in the Middle East 1944.

The Stern Gang

By 1941 Lord Moyne had served in various posts which included Kenya and as acting secretary of the Polish Relief Fund. He celebrated Empire Day (24th of May) by speaking on the colonies, protectorates, and mandated territories that the world war had given a new strength and power to Empire Unity.[26]

By 1941 Lord Moyne had served in various posts which included Kenya and as acting secretary of the Polish Relief Fund. He celebrated Empire Day (24th of May) by speaking on the colonies, protectorates, and mandated territories that the world war had given a new strength and power to Empire Unity.[26]

Not everyone agreed and especially on the question of Palestine. An Irish Jew named Gerald Goldberg writing in the journal, The Bell noted that …’’it was time that the British stopped their nefarious policy of divide and rule and get out of Palestine.’’[27]

Goldberg’s views had some resemblance to the Jewish radical Abraham Stern. For Stern the Arab-Jewish conflict was not the result of any fundamental antagonism between them, it was a divide-and- rule policy by the British who wanted to maintain its dominance in the Middle East.[28]

Militant Jewish nationalist group Lehi viewed the Arab-Jewish conflict not as the result of antagonism between them, but of a divide-and- rule policy by the British who wanted to maintain its dominance in the Middle East

This concept was nothing new and it had parallels with Irish nationalism and like the extremists of that country, who made similar arguments with regard to sectarian divisions within the north of Ireland. Stern’s followers, the Lehi (Fighters for the Freedom of Israel), also called ‘Stern Gang’, conducted an unrelenting campaign of terror against the British authorities.

The ferocity of their actions was designed to force the British to relinquish control of the Palestine mandate. To implement these objectives, Stern unsuccessfully attempted to establish contacts with German representatives in Istanbul and forge an anti-British alliance with Arab nations[29].

This was similar to the manner in which Irish Republican Army (IRA) member Sean Russell (who also saw himself as an anti-colonial rebel) displayed an anti-British fanaticism that sought the assistance of the German army in securing Irish independence. The plans were aborted when Russell died of a perforated ulcer on board a U-boat destined for the Dingle peninsula.[30]

Stern’s movement, which numbered no more than a few hundred, continued to commit acts of terror after he was shot and killed by the British in 1942, In fact, both the Stern Gang and the extremist Zionist group National Military Organisation or ‘Irgun’, rejected the policy of restraint. ‘’Strike the British and Arab murderers, ‘’ one pamphlet declared. ‘’End the passive self-defence! We shall go to the nests of murderers and destroy them’.[31]

Minister resident in the Middle East

This was the volatile situation which 63-year-old Lord Moyne inherited in 1944, when he succeeded Mr. G. R Casey as Minister resident in the Middle East, responsibility for an area that stretched from Tripoli to eastern Persia. [32]

In the early part of the war Lord Moyne made a speech suggesting Jews be brought out of Nazi control to anywhere in the world. Michele Guinness claimed that this memory lingered on as a festering sore that re-opened when he was appointed to oversee the British policy of limited Jewish immigration to Palestine.

Lord Moyne inherited in 1944, when he succeeded Mr. G. R Casey as Minister resident in the Middle East, responsibility for an area that stretched from Tripoli to eastern Persia.

Moyne’s son, Bryan Guinness (Later Lord Moyne II) was convinced of his father’s sympathy towards the Jews and had a vivid recollection of the intense anger felt by his father at the indignities and atrocities inflicted on the Jews in Austria after the Anschluss, before the onset of the genocide. Lord Moyne’s sympathies, however, may have been based more on general political principles than genuine affection. He was interested in the rights of peoples, in the preservation of racial identity, and in that context, made certain comments about Jewish racial characteristics which appeared patronising at the least, downright anti-Semitic at worst.[33]

This was a period of dramatic upheaval and the time of the notorious ‘saison’ or ‘hunting season’ in Palestine was getting underway, in which Zionist organisations, divided over the correct attitude towards the British authorities in Palestine, came to blows with each other. This brought relationships between the Haganah, the main paramilitary Jewish organisation and Irgun almost to the point of civil war, when the Haganah agreed to collaborate with the British authorities and began to hand over Irgun members to the police.[34]

The situation was further antagonised by the assassination attempts on the High Commissioner, Sir Harold McMichael by Stern’s followers in August of 1944, which reminds the Irish reader of the failed assassination of Lord French, the Lord Lieutenant of Ireland by the IRA in 1919. McMichael’s injuries had not been life threatening. Not so fortunate were two Jewish detectives and a much hated British Sgt. W, who were also shot by Stern in the same month.[35]

Lesser men may have been dismayed by the turn of events. However, Lord Moyne remained resolute in his belief in compromise between Jews and Arabs. He dismissed his Egyptian police escort and a police guard that was stationed at his house day and night.[36] Yet, he did recognise the mounting pressure on the British in Palestine and he wrote that ‘the [attempted] murder of the High Commissioner was for political motives and by agents of a definite extremist political group or groups in Palestine, encouraged by statements ‘amounting in effect to incite violence by high Jewish circles in Palestine.’[37]

However, the idea of murdering the British Minister in the Middle East had originated in the mind of Stern as according to Nathan Friedmann-Yellin. Stern felt that such an attack would be a lesson to the Yishuv (Jewish community in Palestine) that the fight was not against the British Administration in Palestine but against Britain herself.

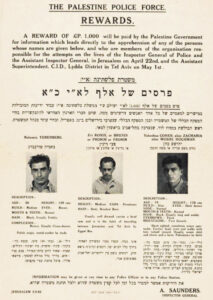

In November 1944, Moyne was assassinated near his office in Cairo by two members of Lehi or the ‘Stern gang’. They were later hanged.

Therefore, it was not motivated by revenge but by thedesire for independence. It is interesting to note that they dismissed the plot against the previous minister R. G Casey (who was of Irish descent) as he was an Australian and his death would not make required impression on the world. However, the death of an Irish born figure appeared to be valid.[38]

In November 1944 (just three months after the attempt on High Commissioner Mac Michael’s life) two Stern Gang members, Eliahu Hakim and Eliyahu Bet-Zuri waited for Lord Moyne near his Cairo residence when he was shot in the neck, chest and abdomen as he stepped into his automobile in front of his home. His chauffer was killed instantly. Lord Moyne had once survived the gun. This time the overseer of limited Jewish immigration expired in a British military hospital in Cairo -several hours after the event.[39] The murderers themselves narrowly escaped lynching at the hands of Egyptian passers-by and they were apprehended soon after.[40]

The aftermath

By the next week a forensic examination had established that the pistols wielded by the killers had been used in a string of murders of British police officers by the Stern gang. Nevertheless, the decision had already been made not to concentrate too much on the ‘masters’ of the assassins last in doing so, ‘drastic action …should be directed against the whole Jewish community in Palestine’. Instead, all attention was to be concentrated on the two killers.[41]

The gunmen, Hakim and Bet-Zuri, had their final say before being hanged, following in the footsteps of many Irish ‘martyrs’ from Robert Emmet to that of the Fenians – boldly using their trial to proclaim their aspirant nation’s cause.

The gunmen, Hakim and Bet-Zuri, made a defiant speech before being hanged, like Irish martyr Robert Emmet and others.

The killing was condemned by Jewish leaders and newspapers in Britain and Palestine, but significant damage had been done to the Zionist cause. By a twist of fate, the assassination, preceded by only a few days the scheduled cabinet discussion on the Cabinet Committee recommendation to partition Palestine. Prime Minister Winston Churchill irritated that ‘Jewish terrorists’ had killed his own personal friend at a time when Churchill had been fighting a lonely struggle on behalf of the Zionist cause. Disappointed, he cancelled the item and it was never revisited by his Cabinet.[42]

There were further repercussions off the back of the assassination. In June of 1945 Churchill stated that the Palestine question would have to wait until the allies were seated around the peace table.

The only concession made to the Jews thereafter (by the new labour government in Britain) was the continuation of the White Paper quota of 1,500 Jewish immigrants a month.[43] Inevitably, the British failed to control the violence, and in 1947 the United Nations voted to split the land into two countries. Arab leaders vigorously reject Zionist offer for a two-state solution in Palestine.

What was achieved by the assassination?

The assassination was headline news all around the world. If it did nothing else, it highlighted the cause of militant Zionism, just as the Invincibles’ 1882 assassination of the Chief Secretary and Undersecretary for Ireland illuminated their cause. This argument is highlighted by an interview conducted by Ernest Evans in 1975 of Yallin -Mor (a leading member of the Stern gang) who noted that because of censorship, the plight of Jewish refugees was not receiving any publicity that this policy would be ‘’forced into the open’’ by coverage of the death of a prominent British official.[44]

Moyne was killed not because of his own views but simply the office that he held.

In the end, the character and political views of Lord Moyne were irrelevant. As Bernard Wasserstein has pointed out, he was killed merely because of his office. In fact, the murder had been planned even before he had taken office. It was only in the face of strong indictment that propaganda covering Lord Moyne’s wrongs against the Jewish people really came to the fore. Interestingly, Lord Moyne’s attitude towards the Jews was more favourable in the latter stages of his life.[45]

In a twist of events in 1975, Egypt returned the bodies of Ben Zuri and Hakim to Israel in exchange for 20 prisoners from Gaza and Sinai.

The remains of the gunmen, which had been returned from Cairo after 30 years, were buried with full military honours on Mount Herzl, final resting place of Israel’s Prime Ministers. This contrasted with the Irish Invincibles who had assassinated British political figures in Ireland, who remained buried in the prison grounds of where they were hung, and it is highly unlikely that An Post (the Irish Postal Service) will issue a stamp in their memory as was done in Israel for the assassins of Lord Moyne.

The Irish Press noted that thousands of Israelis had gathered to make an emotional farewell in Jerusalem. Speakers at the funeral emphasised the fact that Lord Moyne’s assassination was carried out just as the Jewish people were undergoing the Nazi holocaust in Europe. Its aim was, they argued, to arouse world public opinion and the conscience of British mandatory authorities who had closed the doors to Jewish immigration.

Ireland and Israel today

Today the Dail has passed a resolution condemning Israel’s de facto annexation of territory in the West Bank and forced displacement of Palestinians therein. The relationship between Ireland and Israel is at an all-time low. Gone are the times when Irish nationalists felt a common bond with the Jews of Palestine, and it is highly unlikely that a forest will be named after an Irish leader like De Valera in the near future. Lord Moyne is just one victim of a divisive conflict that continues to rage.

Today, Irish sympathy appears to be predominantly with the Palestinian people in the West Bank and Gaza.

However, this article does not wish to paint, Zionists or Israelis as monsters. As Primo Levi stated of monsters ‘they are too few in number to be truly dangerous.’ Simplistic rhetoric does nothing to shine a light on the complexity of the issues involved.

Legacy

Lord Moyne’s true legacy is perhaps his philanthropy or the results of his extensive travel which he managed to combine with scientific interest.

Lord Moyne’s true legacy is perhaps his philanthropy or the results of his extensive travel which he managed to combine with scientific interest.

What’s more, his discovery of a group of pygmies (nigritos) inhabiting the Aiome foothills of the middle Rama region of New Guinea was significant at the time. [46] In his book ‘Walkabout’ 1936 he describes the course and results of an expedition.[47]

As chairman of the Royal Commission he travelled 21, 000 miles across the West Indies. The detailed Moyne Report outlined many of the major problems which beset the Caribbean in 1938.[48] However, for many his legacy started and ended in Palestine and is forever tied to his assassins who were hanged in March of 1945.

There are several different interpretations of Lord Moyne. He was, according to some, an Arabist or to others, a committed Zionist. Other still maintain that he cared little for both and was simply a tool of British influence. Nonetheless, he did not live long enough for his legacy in the Middle East to be obliterated or vindicated.

Lord Moyne’s true legacy is perhaps his scientific and anthropological work. The Institute of Preventative Medicine in Trinity College Dublin is named after him today.

Looking back at those events in 1985 , Bryan Guinness wondered about what might have been, ‘ it can be no more than speculation to suppose that if my father had not been murdered and if he could have achieved agreement before the end of the war on a partitioned Palestine -the events that have occurred might have been avoided. But as his forefathers had foreseen only too well, partition is no guarantee of peace. [49]

References

[1] Irish Independent October 02, 1950

[2] George R. Clerk Obituary: Lord Moyne, D. S. O. The Geographical Journal

Vol. 104, No. 5/6 (Nov. – Dec. 1944), pp. 214-215

[3] Michelle Guinness The Guinness Spirit Brewers and Bankers Ministers and Missionaries (London 1999) p. 462

[4] Derry Journal June 28, 1916

[5] Brian Bond, Staff Officer: The Diaries of Lord Moyne 1914-1918, p.98

[6] Irish Times July 06, 1916

[7] Irish Examiner Aug 07, 1920

[8] Irish Times Dec 17, 1920

[9] Freemans Journal April 1921.

[10] Ireland The Revolutionary Years: Photographs from the Cashman Collection Ireland 1910-30 Edited by Louis McRedmond (Dublin, 1992) p. 59

[11] Irish times 28 Jan 1922

[12] Freemans Journal Feb 11, 1922

[13] See: Staff Officer: The diaries of Walter Guinness (Lord Moyne) 1914-1918 (ed) Brian Bond

[14] Irish Times Feb 13, 1919

[15] Irish independent Oct 02, 1922

[16] BM https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/term/BIOG126475

[17] Proceedings of the Royal Irish Academy, Vol. XLII, Appendix CIII, pp 17-26, 1934-35

[18] Belfast Newsletter July 25, 1935

[19] Michelle Guinness The Guinness Spirit Brewers and Bankers Ministers and Missionaries (London 1999) pp. 462-3

[20] The Mandate System encompassed territories which were entrusted to a mandatory power, whose duty was to rule with the benefits and the ultimate of the natives in mind.

[21] Michael Adams What Went Wrong in Palestine? Journal of Palestinian Studies Vol. 18, No. 1, Special Issues: Palestine 1948 (Autumn, 1988) p. 74.

[22] Daniel Byran A High Price: The Triumphs and Failures of Israel Counterterrorism (Oxford 2011) p. 15.

[23] Akiva Elder and Amnon Barzilay Yitshak Shamir: Man, of Mystery Journal of Palestine Studies Vol. 13, No. 2 (Winter, 1948) p. 168

[24] Yitzhak Rabin The Rabin Memories (London 1979) pp. 264 465

[25] Irish Examiner, June 30, 1939

[26] Belfast Newsletter, May 24, 1941

[27] RORY MILLER The look of the Irish: Irish Jews and the Zionist project, 1900—48 Jewish Historical Studies Vol. 43 (2011), p. 210.

[28] Bernard Wasserstein The Assassination of Lord Moyne Transactions & Miscellanies (Jewish Historical Society of England) Vol. 27 (1978-1980) p. 75

[29] Cary David Stanger A Haunting Legacy: The Assassination of Count Bernadotte Middle East Journal. 42, No. 2 (Spring, 1988) p. 264.

[30] David O ‘Donoghue State within a State: The Nazis in Neutral Ireland Dublin Historical Record

Vol. 60, No. 2 (Autumn, 2007) p. 169.

[31] Daniel Byran A High Price: The Triumphs and Failures of Israel Counterterrorism (Oxford 2011) p. 15.

[32] Irish Times Jan 29, 1944

[33] Michele Guinness The Guinness Spirit: Brewers and Bankers, Ministers and Missionaries (London, 1999) p. 465.

[34] Joseph Heller ‘Neither Masada-Nor Vichy’: Diplomacy and Resistance in Zionist Politics, 1945-1947 The International History Review Vol. 3, No. 4 (Oct. 1981) p. 5

[35] Y. S. Brenner ‘The ‘Stern Gang’ 1940-48 Middle Eastern Studies. 2, No. 1 (Oct. 1965), p 12.

[36] Hansard The Murder of Lord Moyne Volume 133. Debated on 9 November 1944.

[37] Simon Ball THE ASSASSINATION CULTURE OF IMPERIAL BRITAIN, 1909-1979 The Historical Journal Vol. 56, No. 1 (MARCH 2013), p 242.

[38] Bernard Wasserstein Transactions and Miscellanies (Jewish Historical Society of England) Vol. 27(1878-1980) p. 82

[39] Jewish Post November 10, 1944

[40] Evening Echo November 07, 1944.

[41] Simon Ball THE ASSASSINATION CULTURE OF IMPERIAL BRITAIN, 1909-1979 The Historical Journal

Vol. 56, No. 1 (MARCH 2013), p 242.

[42] Michael J. Cohen Direction of policy in Palestine, 1939-45 Middle Eastern Studies Vol. II, No. 3 (Oct. 1975) p. 255.

[43] Joseph Heller ‘Neither Masada- Nor Vichy’: Diplomacy and Resistance in Zionist Politics, 1945-1947 The International History ReviewVol. 3, No. 4 (Oct. 1981) p. 545.

[44] Ernest Evans The Mind of a Terrorist: How Terrorists see strategy and morality World Affairs, Vol. 167 No. 4 (Spring 2005), pp. 175-179

[45] Bernard Wasserstein Transactions and Miscellanies (Jewish Historical Society of England) Vol. 27(1878-1980) p. 82

[46] H. J. Braunholtz 121. Note ON A SPECIAL EXHIBITION OF ETHNOGAPHICAL OBJECTS FROM NEW GUINEA AND INDONESIA COLLECTED BY LORD MOYNE, P.C., D.S.O: man Vol. 36 (June., 1936) p. 95.

[47] George R. Clerk Obituary: Lord Moyne, D. S. O. The Geographical Journal

Vol. 104, No. 5/6 (Nov. – Dec. 1944), pp. 214-215

[48] Lord Moyne The West Indies in 1939 The Geographical Journal, Vol. 96, No. 2 (August 1940) pp. 85.

[49] Michele Guinness The Guinness Spirit: Brewers and Bankers, Ministers and Missionaries (London, 1999) P. 467