‘A Fiend in Human Shape’? The Life and Crimes of Thomas D. Huckerby

By Seán William Gannon

The behaviour of the Black and Tans, the mostly British recruits into the Royal Irish Constabulary in 1920-21, has always been controversial.

They and the Auxiliary Division were certainly responsible for scores of reprisals against both people and property during the Irish War of Independence. But why was their behaviour towards Irish insurgents and civilians so brutal? A look at one Black and Tan, Thomas Huckerby, who was known in County Limerick as ‘a fiend in human shape’ may give us some answers.

The Abbeyfeale shootings

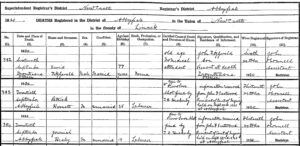

In a survey of the General Register Office (GRO) death records for county Limerick in 1920, two in particular stand out. This first is that of Patrick Harnett, a 25-year-old postman from Barrack Street, Abbeyfeale. The second is that of his friend, 18-year-old Jeremiah Healy, an apprentice blacksmith from Abbeyfeale Hill, a short distance outside the town. Both men died together; they were shot dead by a Black and Tan named Thomas Darrell Huckerby on the evening of 20 September 1920, as they were walking out the Castleisland Road.

In his evidence to the consequent military court of inquiry, a RIC Auxiliary Division cadet in temporary de facto charge in Abbeyfeale station, Colonel Owen Latimer, stated that Huckerby had reported to him directly after the shooting to give him his version of what had occurred:

I was standing at the barrack gate and said “good evening” to two young men who were passing. They took no notice and I followed them as they looked suspicious. They kept looking back and then broke into a run. I ran after them, and they went through a hedge on the right of the road. I shouted to them to halt and, as they wouldn’t stop running, I shot them’.[1]

Constable Thomas Huckerby shot dead two two young men in field at Abbeyfeale in September 1920.

Questioned by the solicitor representing the victims’ families as to whether he thought anything strange about Huckerby’s story, Latimer stated that ‘the shootings struck me as being rather drastic under the circumstances’, and the three British soldiers who comprised the court evidently agreed.[2]

For they declined to provide the standard cover for a killing by Crown Forces at that time – a finding such as ‘shot in the course of duty’ or ‘justifiable homicide by the police’ – and instead entered a verdict of ‘death due to revolver shots fired by T. D. Huckerby’. As Thomas Toomey has observed, this verdict, which the GRO duly recorded, ‘clearly insinuated that the court [believed] Huckerby had murdered the unfortunate young men’.[3]

At this remove, the precise circumstances in which Huckerby killed Harnett and Healy cannot be conclusively known. However, the available evidence does support an ‘insinuation’ of murder.

According to Latimer, who examined the bodies in the immediate aftermath of the shootings, they were lying in a field, one metre apart on their backs, and just three metres inside the hedge that bordered the road.

Both men had been shot once in the head, from what direction he could not say, and an examination of Huckerby’s gun revealed that just three bullets had been discharged. Although Huckerby was an acknowledged crack shot, the crime scene that Latimer described clearly belied his contention that he shot Harnett and Healy as they were running away.[4] Far more consistent with this scene were the findings of an investigation into the killings conducted in autumn 1923 to assist in the adjudication of a compensation claim lodged by Healy’s father, Daniel.

The Irish Free State army’s director of intelligence, David Neligan, who oversaw this investigation, concluded that Huckerby had ordered the two men off the road and through the hedge into the field and ‘put them on their knees and shot them side by side’.[5] This was also the view of the Abbeyfeale IRA; in his testimony to the Bureau of Military History many years later, company captain James Collins stated that Huckerby had ‘halted the two men, took them into a field and shot them dead, through the forehead’.[6]

Neligan ended his report by noting that ‘no reason can be given’ for the murders of Harnett and Healy and none has since been firmly established.[7] It has been suggested that they were targeted as IRA Volunteers. For, despite claims then and since that they had no involvement in the guerrilla war for an Irish Republic, Healy and Harnett were in fact both members of the IRA’s West Limerick Brigade.

There are a few isolated references in Military Service Pension Collection files pertaining to the two men suggesting that they were actually killed while on active service.[8] However, the evidence for this is extremely unclear and it is, in any case, highly unlikely that Huckerby knew of his victims’ IRA status. Neligan himself was unaware: he reported that Healy ‘may be properly regarded as having been a neutral during the Anglo-Irish War [who] never associated himself with politics in any way’.[9]

‘Motiveless Malignity’?

But, for republicans of Neligan’s generation, no specific reason was required for such seemingly random, ‘unprovoked’ crimes. They attributed them to what Samuel Taylor Coleridge termed ‘motiveless malignity’ deriving from the perceived low moral characters of British Black and Tans and/or their brutalization by service in the Great War.[10]

These men it was, and indeed has long since been said, were variously ‘jail-birds and down-and-outs … hastily recruited’ from ‘the criminal classes and the dregs of the population of English cities’; ‘the offscourings of English industrial populations’; and ‘the scum of London’s underworld’. ‘Past masters of the arts of murder, looting, arson and outrage’, they were the ‘dirty tools for a dirty job’ that the Crown Forces in Ireland required.[11]

Such killings were often ascribed to the low moral characters of British Black and Tans or their brutalization by service in the Great War

The idea that the Black and Tans’ inherently base natures were further brutalized by their experience of the Great War also dates from the time when, as John Lawrence has noted, British society was haunted by fears that ‘ex-servicemen, the general public, the [apparatus of] state, or perhaps all three, had been irrevocably “brutalized” by the mass carnage of four-and-a-half years of war’.[12]

In his classic 1971 survey Ireland Since the Famine, F. S. L. Lyons applied this idea to the Black and Tans: their ‘ruthlessness and contempt for life and property … stemmed partly’, he argued, ‘from the brutalization inseparable from four years of trench warfare’.[13]

Although a clean police record and good British Army reference was officially required of all RIC recruits, a few Black and Tans with criminal records did find their way in. David Leeson puts the figure at 50 to 60 out of 8,000 (or 0.6 percent of the intake) a figure scarcely supporting claims such as that of former republican propagandist, Frank Gallagher, that ‘every thief, drug addict, madman and murderer could come in’.[14]

On the contrary, an examination of the RIC General Registers of Service, together with civil registration records and census returns, reveals the overwhelming majority of Black and Tans to have been ordinary, everyday men.

The so-called ‘brutalization thesis’ has proved more resilient, a function perhaps of the ongoing historiographical debate prompted by the publication of George Mosse’s Fallen Soldiers in 1990, together with its superficially common-sense appeal.[15] However, as Anne Dolan has argued, there is simply ‘no way to gauge [brutalization] beyond personal experience’ and data on the personal wartime experiences of Black and Tans has not been collected.[16]

In fact, the destruction of great swathes of Great War-era British military service records in 1940 (when the Arnside Street Army Records Centre was hit by a German incendiary bomb) means that, in over 60 per cent of cases, it can never be.

The case of Thomas Huckerby

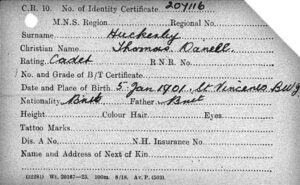

RIC Constable Thomas D. Huckerby presents an illustrative case in point. Far from being drawn England’s urban criminal classes, he was from St Vincent in the then British West Indies. He was born there on 5 January 1901, the first of twelve children born to Mildred Darrell, an indigenous clergyman’s daughter, and Thomas Huckerby, a Methodist missionary from Staffordshire.

Nor was he brutalized by the Great War; he enlisted in the British West Indian Volunteer Force in 1915, but was not deployed overseas. Accompanied by his father, Huckerby travelled to England via New York in early autumn 1918, where he joined the Royal Naval Reserve.

Thomas Huckerby was a 19 year old missionary’s son and had not served in the First World War.

However, he was demobilized five months later and turned to the RAF. He enlisted there in September 1919 but was discharged as ‘physically unfit’ in December on account of ‘debility following malaria’. He then briefly worked as a clerk before joining the RIC on 30 April 1920 as Constable no. 71352.

How then can we account for Huckerby’s crime? In seeking to explain the Black and Tans’ frequent excesses, Lyons also referenced what he termed ‘the continual and intense strain imposed upon them by service in Ireland’, and this insight casts much light on his case.[17]

For, the 19-year-old Huckerby’s emergence as, in Toomey’s words, ‘by far the most notorious of all the Black and Tans in County Limerick’, with a reputation as what one Limerick Volunteer termed ‘a fiend in human shape’, commenced with a significant traumatic event, viz. an IRA assault on him and an RIC colleague in Shanagolden on 26 August 1920.[18]

The affair at Shanagolden

Seven years afterwards, this colleague (a long-serving Irish RIC constable named William Hall) recorded an account of this assault which gives a sense of the intense humiliation that both policemen endured:

I was in Shanagolden accompanied by [Constable Huckerby] to see the doctor and when in the dispensary a party of eight armed men came in and took us out pointing their guns at our head and body, marched us to the lower end of the village, stripped us of our clothing and boots, then marched us through the streets and, I am certain, were bringing us to a place to shoot us, but for the timely arrival of [the local priest] who interfered. So after marching us through the village streets for one hour and a quarter they sent us away without clothes or boots and [we] had to get back to [Foynes] barracks, a distance of three miles in that condition.[19]

This account is broadly corroborated by other sources, including that of one of IRA Volunteers who was present.[20]

Huckerby was stripped and humiliated by the IRA at Shanagolden in August 1920.

The extent to which Huckerby felt degraded and shamed by this experience was laid bare in evidence heard at the Limerick Quarter Sessions in October where he applied for compensation for ‘ill-treatment and assault’.[21]

Advised by a sceptical county court judge that he was ‘unsatisfied that any serious injury was inflicted on him’, Huckerby’s counsel, Mr Gaffney, submitted that his client had been ‘physically damaged … dragged out of the [dispensary], forcibly assaulted, and deprived of his clothes’, which were then burnt. Huckerby himself told the court that that he had been hospitalised in consequence of being made walk barefoot to Foynes: ‘my feet were bleeding: I could not walk for seven days afterwards’.[22]

Moreover, and more significantly, Gaffney stated the ‘mental damage of being humiliated and degraded before a number of people had a very serious effect’ upon his client. He was, he said, ‘mentally injured by the humiliation of being marched up and down the village in a state of nudity’ while ‘everyone laughed and jeered’.[23]

Although no reference was made to it in court, the possibility that this verbal abuse included racial slurs cannot be discounted. Huckerby’s biracial heritage was evident (US immigration changed his ‘race or nation’ from the ‘English’ his father put down to ‘West Indian’, and his RAF record described his complexion as ‘dark’) and it was remarked upon locally in Limerick: the Harnett’s family solicitor subsequently described Huckerby as being of ‘mixed negroid blood’ while one of the Shanagolden Volunteers referred to him as ‘a half caste’.[24]

‘Iron entered Huckerby’s soul’

Recalling the incident thirty years later, Limerick’s then acting RIC county inspector John Regan identified the Shanagolden assault as the moment when ‘the iron … entered Huckerby’s soul, and he became a menace’ to the people of Limerick. And the available evidence bears this out.[25]

That night Huckerby took a central part in the reprisal that inevitably followed IRA attacks on the RIC at the time. During this reprisal, he shot dead John Hynes, a 74-year-old local man returning home from the pub.

This made Huckerby a marked man, and he was quickly transferred for his safety to Abbeyfeale. There, as its local IRA company captain James Collins later recounted, he proved ‘a thorough blackguard from his first day in the town, holding up the inhabitants at the point of a revolver and visiting public houses where he terrorized the owners and the public generally’.[26]

After the affair at Shangolden, ‘the iron … entered Huckerby soul, and he became a menace’ to the people of Limerick, carrying out several killings.

For this and Hynes’ killing, Abbeyfeale Brigade commander Seán Finn passed a death sentence on Huckerby and ordered an ambush on an RIC patrol in which he routinely took part on 19 September, two days before the murder of Harnett and Healy.

Huckerby escaped the IRA’s retribution as he was not rostered that night but two of his colleagues in Abbeyfeale barracks were killed: Constables John Mahony and James Donohue from Cork and Monaghan respectively.[27] A large party of RIC (including Black and Tans like Huckerby), and Auxiliaries rampaged through Abbeyfeale in reprisal the following night, assaulting residents and burning buildings. Huckerby himself took a prominent part, a part which included the detonation of an explosive device outside the house of James Collins and an assault on his elderly father.[28]

Why Hartnett and Healy?

Huckerby murdered Patrick Harnett and Jeremiah Healy the next evening. Healy’s father, Daniel, believed that they were killed in further reprisal for Constables Mahony and Donohoe’s deaths and correspondence in his Military Service Pensions Collection file demonstrates that he remained convinced of this all his life.[29]

It was widely believed that Hartnett and Healy were killed in reprisal for the deaths of two RIC men the day before.

Retribution for their killings may have well been on Huckerby’s mind. But why did he exact it on Harnett and Healy? A clue perhaps lies in his statement to Colonel Latimer in their murders’ immediate aftermath: ‘I was standing at the barrack gate and said “good evening” to two young men who were passing. They took no notice’.

Did this perceived disrespect, whether intentional or unwitting on the men’s part, trigger in Huckerby the rage and insulted honour over his humiliation in Shanagolden which, as his court appearance four weeks later demonstrated, he still felt so keenly? Did he decide that this occasion, Irish ‘insolence’ would be punished and, in this context, shoot them dead?

Whatever its precise motivation, Huckerby’s murder of Harnett and Healy certainly alarmed his superiors. Yet, he was not punished or (on the evidence available) even officially reprimanded for the crime.

Transferred to Limerick

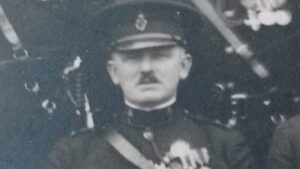

The extent of institutional RIC censure was his removal to Limerick city where, as John Regan put it, he could be kept ‘under our eye’.[30] But he soon proved a problem there too.

According to Regan, Huckerby ‘carried a revolver strapped to each thigh and was completely fearless, walking alone around the worst streets of the city with impunity’ and on at least one occasion, attempted seriously to kill, throwing into the Shannon to drown a man who threatened a girl with whom he was ‘walking out’ with hair cutting.[31]

And still Regan, who not only took a tolerant approach to police reprisals, but appears to have developed a fascination with Huckerby, did not rein him in. (Regan described Huckerby as ‘a public school type of fine physique and excellent manners … ’undoubtedly, the most extraordinary man I had met’).[32]

The RIC commander in Limerick, John Regan, admired Huckerby and said he was ‘undoubtedly, the most extraordinary man I had met’

There are some indications that Huckerby was involved in the shooting of two men at Grange Cross on 20 November 1920, not least of all, the fact that, as Toomey observes, Regan finally took action against him by transferring him to the RIC’s Phoenix Park Depot in this incident’s immediate aftermath. Within one month, Huckerby was gone.

He resigned from the RIC on 27 December with unspecified ‘disciplinary charges pending’ and travelled to London where he lodged at the Police Institute hostel on Adelphi Terrace. By February he was dead. The recorded cause was ‘acute yellow atrophy’, a then extremely rare diagnosis that raises more questions than it answers provides.

‘Even ordinary men would have committed atrocities’

That a 19-year-old clergyman’s son from the British West Indies could earn himself the reputation of ‘a fiend in human shape’ and ‘the most notorious of all the Black and Tans in County Limerick’ lends support to David Leeson’s thesis that historians of the Irish War of Independence have tended to overvalue dispositional explanations (i.e. looking for explanations in the character and background of police recruits) at the expense of circumstance-based or situational assessments when analysing the actions of the Black and Tans.[33]

Huckerby resigned from the RIC in December 1920 and died of illness two months later. His record suggests that ordinary young men could become ‘fiends’ while serving in Ireland.

Building on Lyons, he argues their excesses essentially derived from the situation into which they found themselves thrust – an oftentimes vicious guerrilla insurgency in a foreign country against which they formed a significant part of an entirely inadequate front line.

Driven by rage at frequently fatal attacks on themselves and their comrades conducted with what appeared to them active societal support, and facilitated by ineffective command, a corporate impunity culture, and an official ambivalence towards reprisals that shaded sometimes into sanction, the Black and Tans imposed what Leeson termed their own ‘form of rough justice’. ‘Even ordinary men’ – men like Thomas D. Huckerby – would, he argues, ‘have committed atrocities under circumstances like these’.[34]

References

[1] Irish Independent, 24 Sept. 1920.

[2] Ibid.

[3] Thomas Toomey, The War of Independence in Limerick, 1912-1921: also covering actions in the border areas of Tipperary, Cork, Kerry and Clare (Limerick, 2010), p. 436.

[4] On Huckerby’s marksmanship, see Military Archives, Dublin (MA), Bureau of Military History witness statements (BMH WS), 1272 James Collins, 5 Oct. 1955, p. 15; Joost Augusteijn (ed.), The memoirs of John M. Regan: a Catholic officer in the RIC and RUC, 1909-48 (Dublin, 2007), p. 162.

[5] MA, Military Service Pensions Collection (MSPC), DP4292 Daniel Healy, Neligan to Mulcahy, 10 Oct. 1923.

[6] The service certificate issued by the Military Service Registration Board to Daniel 15 years later described his son as having been ‘murdered while [Huckerby’s] prisoner’. BMH WS James Collins, p. 18; MA, MPSC, DP4292, Service certificate of Jeremiah Healy, 1 Mar. 1938.

[7] MA, MSPC, DP4292 Neligan to Mulcahy, 10 Oct. 1923.

[8] See, for example, MA, MPSC, DP4196 John Harnett, O’Sullivan to Military Service Registration Board, 13 May 1928; ibid., DP4292 Military Service Registration Board to Department of Finance, 21 Dec. 1933.

[9] In March 1924, the chief superintendent of the Garda Síochána for the ‘Limerick Division’ too reported that Healy had no connection to the IRA. MA, MSPC, DP4292 Neligan to Mulcahy, 10 Oct. 1923; ibid., Redmond to the Department of Finance, 14 Mar. 1933. See also J.D.H., ‘Black and Tans in West Limerick’ in Limerick’s fighting story, 1916-21; told by the men who made it (Cork, 2009), pp 290-303, at p. 293.

[10] The term ‘motiveless malignity’ was coined by Coleridge with reference to the character of Iago in Shakespeare’s Othello.

[11] These quotations from Florence O’Donoghue, Piarais Béaslai, and Donal O’Kelly are cited in D. M. Leeson The Black and Tans: British police and auxiliaries in the Irish War of Independence (Oxford, 2011), pp 84-5.

[12] Jon Lawrence, ‘Forging a Peaceable Kingdom: War, Violence and Fear of Brutalization in Post-First World War Britain’, Journal of Modern History, 75 (2003): 557-89, 557.

[13] F. S. L. Lyons, Ireland Since the Famine (Glasgow, 1973), p. 415.

[14] Frank Gallagher, The four glorious years (Dublin, 1954), p. 103.

[15] Mosse argued that the brutalizating experience of German soldiers in the First World War was a significant cause of political violence in the Weimar Republic and effectively provided a foundation for Nazism. George Mosse, Fallen Soldiers: reshaping the memory of the World Wars (Oxford, 1990).

[16] Anne Dolan, ‘The British culture of paramilitary violence in the Irish War of Independence’ in Robert Gerwarth & John Horne (eds), War in peace: paramilitary violence in Europe after the Great War (Oxford, 2012), pp 200-15, at p. 212.

[17] Lyons, Ireland since the Famine, p. 415.

[18] Toomey, War of Independence in Limerick, p. 317; ‘Volunteer’, ‘The IRA campaign in West Limerick’ in Limerick’s fighting story, pp 249-89, at p. 265.

[19] British National Archives (TNA), Colonial Office files, Irish Grants Committee (CO 762), CO 762/122/7, William Hall, grant application, 10 Feb. 1927.

[20] See, for example, Augusteijn, Memoirs of John Regan, p. 162; MA, BMH WS 1273 Denis McDonnell, 6 Oct. 1955; report of Lord Monteagle, published in Timothy A. Donovan, In the shadow of Shanid: the life of captain Timothy B. Madigan, 1897-1920 (Limerick, 2010), pp 196-201; Irish Independent, 28 Aug. 1920. The assault was in reprisal for what the Volunteers believed was an attempt by members of the Foynes RIC to burn Shanagolden creamery the previous night.

[21] Limerick Leader, 20 Oct. 1920.

[22] Ibid. The judge awarded Huckerby £100 in compensation but said that in so doing he ‘only took into consideration the physical injury’, an injury which Huckerby clearly exaggerated.

[23] Ibid.

[24] The fact that Huckerby gave Somerset as his birthplace when applying for the RIC may be significant in this general context. TNA, AIR 79/2844, RAF service record 336803: Thomas D. Huckerby; MA, BMH WS 1273 Denis McDonnell, 6 Oct. 1955, p. 3; TNA, CO 762/60/1: John Harnett, grant application.

[25] Augusteijn, Memoirs of John Regan, p. 162. Huckerby is pseudonymised as ‘Wellarly’ in Regan’s memoir.

[26] MA, BMH WS James Collins, pp 15-16.

[27] Interestingly, these constables were likely well known to Patrick Harnett’s mother, Nora, as she had worked as a ‘housekeeper’ in Abbeyfeale RIC barracks until six weeks before. Why she left is unclear. According to the family’s MSPC compensation claim for Patrick’s death lodged in the mid-1930s, she willingly resigned (after 18 years’ service) in response to the IRA’s June 1920 demand that women desist from such work. Yet, in an earlier claim lodged with the Irish Grants Committee in London (which compensated for losses incurred on account of Crown loyalty between the July 1921 Truce and the end of the Irish Civil War), they claimed that she had been intimidated out by the IRA. MA, MPSC, DP4196 John Harnett, Harnett to Department of Defence, undated, c. August 1938; TNA, CO 762/60/1, John Harnett, grant application.

[28] Toomey, War of Independence in Limerick, p. 434.

[29] Ibid., Healy to Crowley, 3 Nov. 1933; Healy to Department of Defence, 13 Jan. 1954.

[30] Augusteijn, Memoirs of John Regan, p. 162.

[31] Ibid.

[32] Ibid., p. 163.

[33] Toomey, War of Independence in Limerick, p. 317.

[34] Leeson The Black and Tans, pp 191, 224. See also Dolan, ‘British culture’, pp 202, 204-7.